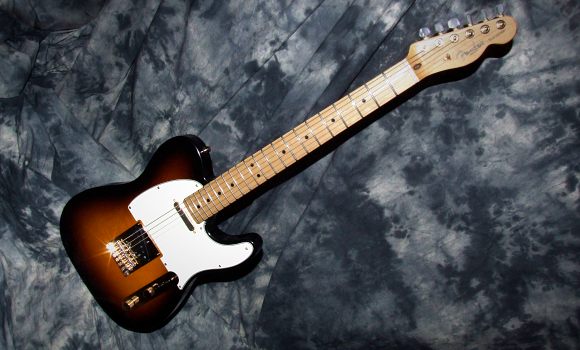

Tele-bration: The Telecaster Celebrates 60th Anniversary

One of the most illustrious names in the guitar universe celebrated its 60th anniversary this past year. When the Fender Telecaster first appeared in the Fifties, it was something brand new—a blank canvas, if you will, awaiting a handful of gifted mid–20th-century guitarists to create new modes of expression around the bright, steely tone of this new kind of solidbody guitar. Today, the Telecaster legacy is still going strong—the model is the guitar of choice for many young players currently making their own history.

“The Telecaster is an heirloom instrument,” says Fender senior vice president of marketing Richard McDonald. “You can play it all through your career and hand it down to your son or daughter. Today, we make Telecasters in a million different variations. But in essence, they’re still Teles. They still have the same appeal to players: simplicity, straightforwardness and stability day in and day out. The Tele is a no-nonsense instrument. There’s no place to hide on one. You can’t jump on the whammy bar when things get weird. You’re just going to have to play your way out of it. But the other side of that is that the Tele doesn’t mask the individuality of the player.”

The classic and pragmatic simplicity of the Telecaster design lies at the heart of its enduring popularity and eminent suitability to just about any playing style and musical genre. The icily resonant scream of the Tele’s bridge pickup and the deep bass warmth of that slim, silver neck pickup have played a major role in country, blues, rock, soul, metal and even jazz. Guitar legends of every musical stripe have made history on a Tele or its single-pickup cousin, the Esquire, among them Muddy Waters, James Burton, Keith Richards, Steve Cropper Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Roy Buchanan, George Harrison, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Morello, Bill Frisell and John 5, to name just a few.

In recognition of the Tele’s infinite variety and rich history, Fender opted to commemorate the instrument’s 60th birthday by creating the limited-edition Tele-bration Series: 12 custom Teles, one for each month of the anniversary year. The models range from historic recreations of significant Tele design innovations to imaginative postmodern variations on the core Tele template. There are Teles in rare and exotic woods, one with TV Jones Filter’Tron pickups and another with a flame-maple body cap that essentially answers the question, “What if a Telecaster were a Les Paul?” Only 500 of each Tele-bration model will be produced, which guarantees their status as collector’s items.

“The Telecaster is such an elegantly simple instrument,” says Fender director of electric guitar marketing Justin Norvell, who spearheaded the Tele-bration project. “But there are so many myriad ways the basic Tele design can be interpreted and reinterpreted, each having its own flavor, some going in a modern direction, some in a thinline direction, some going in an old-school, architectural-salvage direction. We just thought it would be a cool kind of tribute to the platform.”

Further celebrating the Tele’s big Six-O, Fender came up with the 60th Anniversary American Standard Telecaster, an amalgam of vintage Tele design and more modern innovations. “Sometimes with anniversary models you go super blingy,” Norvell says. “And sometimes you go super vintage, like back to year one. But for the 60th Anniversary Tele, we thought, Let’s do a composite, like a greatest-hits of all the years. So the fingerboard radius is flatter and more modern, and the neck shape is a little more of a modern neck shape. But at the same time it has a vintage lacquer finish; it’s not a urethane finish, like on a normal American Standard. When you see a lot of the older blackguard Teles, they have that straw-blond kind of finish. We really went after that. And it has vintage pickups. So we wanted to split the difference between the playability of a modern guitar and the vintage things that influenced the look and tone of the Telecaster. Kind of half yesterday and half today.”

This was more or less the approach that Leo Fender and his partner George Fullerton took when they first came up with the guitar that the world would know as the Telecaster. Together, they looked forward without losing sight of the hard-won experience and know-how they had garnered in the guitar business. Fender and Fullerton were working at an opportune moment in history. The years immediately following World War II were a time of great prosperity and confidence for America. It was an era of rampant technological innovation, much of it aimed at improving the quality of consumer goods and the standard of living for the middle and working classes.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Telecaster is very much a product of that midcentury American spirit of inventiveness and economic egalitarianism. It was designed to be affordable, but to offer great tone and solid, dependable workmanship. Leo Fender himself knew what it was like to have to scrape by on a small amount of money. A former accountant who’d lost his job during the Great Depression, he turned his hand to electronics and opened up a successful radio repair shop, which in turn laid the groundwork for an electric guitar empire.

For most of his life, Leo operated out of the tidy, suburban Southern California town of Fullerton, about 20 miles inland from the beach and 40 miles south of Hollywood. As an outgrowth of his radio repair business, the entrepreneurial Fender began to design and build P.A. equipment and—in partnership with Clayton Orr “Doc” Kaufman—produced a line of Hawaiian-style lap-steel guitars under the K&F brand name. Around 1944, Fender and Kaufman came up with a prototype for a solidbody-electric standard, or “Spanish,” style guitar. A homely instrument with an abbreviated body fashioned out of dark-stained oak, the guitar was never intended for production; it was mainly used to test the ideas for electric guitar pickups that were starting to take shape in Leo’s mind.

By 1946, Leo had parted amicably with Doc Kaufman and launched the Fender Electric Instrument Company out in Fullerton. Two years later, he hired a guitar-playing local guy named George Fullerton, whose remote ancestors had founded the town. Fender and Fullerton went to work on a viable production-model solidbody electric guitar.

“In those days, the only electric guitars musicians were using were the big hollowbody guitars with a pickup inserted somewhere on the top of them,” Fullerton recalls. “I guess they were all right, but they had lots of problems. When you turned the volume up, the feedback was so loud you couldn't stand it. The recording studios hated those guitars. Leo and I decided that was a bad thing.”

In all fairness, Leo Fender was not the first person to think of building a solidbody electric guitar. In this he was preceded by innovations like the Rickenbacker “Frying Pan” guitar (1931–1932), O.W. Appleton’s custom solidbody App guitar (1941–1942) Les Paul’s Log guitar (circa 1941) and the custom solidbodies that luthier Paul Bigsby made in the late Forties. But Leo's instrument—the guitar that became the Telecaster—was the first solidbody electric to be successfully mass-produced.

And that's not just a historical quibble. What's so revolutionary about the Telecaster is the very fact that it was conceived from the ground up for mass production. Fender broke with centuries of luthier tradition, instead basing his guitar design on the streamlined manufacturing techniques and materials of the post-WWII era. His accomplishment in the field of musical instruments is akin to the celebrated modular furniture designs of midcentury modernists like Charles and Ray Eames, and the elegantly utilitarian architectural designs of Richard Neutra. In each of these cases, the goal was to employ the latest manufacturing innovations of the day to provide high-quality, functional objects that were within the budget of the average person. Today, in the early years of the 21st century, when it is routine to discard expensive items like personal computers and cell phones every year or so in the name of technological “progress,” mass-produced goods from 50 years ago—from hairdryers to automobiles to vintage Fender guitars—are collected and treasured as art objects.

The method by which the neck joined the body was one of the most revolutionary aspects of Fender’s guitar design. The traditional means of attaching the neck heel to the guitar body was via an ancient carpentry technique called a dovetail joint, with woodworking glue to strengthen the bond. Fender came up with the idea of using four metal bolts to affix the neck into a pre-routed body pocket. This method made for simplicity and ease of manufacture—as well as repair.

“If the neck got broken on one of those big old hollowbody electrics, or if the body caved in, it would have to go back to the factory for repairs,” Fullerton says. “The musician would have to wait two to four months to get his instrument back, and would have to pay a large repair bill. Most people could barely afford one guitar back then, so they sure didn’t have a spare. And there weren’t rental places around every corner where you could get another guitar. So a working guitar player was out of a job if this happened to his instrument.

“Leo and I decided what we needed to do was design an instrument with all replaceable parts, including the neck, so you could replace any part on the guitar in a few minutes’ time and have the player back to work, without it costing him and arm and a leg. But to come out with that first design took a lot of work.”

Fullerton did the main work on the body shape. (Electronics were Leo’s main forte.) The Telecaster body is simplicity itself: a stylized, miniaturized silhouette of a conventional acoustic guitar, with a body cutaway added for ease of playing.

“We decided we’d make it at least resemble a guitar a little bit,” Fullerton says. Since it was solid wood, we had to make it smaller and thinner than a regular guitar, so it would be light enough for the player to hold without any problem. And we put a cutaway on it so you could get at all the frets.”

While people often think of the Telecaster body as a single slab of wood, it has almost always been fashioned from two, and sometimes three, pieces of neatly joined wood. Its simple shape was partly due to Leo lacking routing equipment sophisticated enough to create bevels, angles or an arched top at this early stage of his company’s development. On a similar note, both the neck and fretboard were both fashioned from the same piece of maple—again breaking with traditional guitar design, wherein a separate fretboard is glued to the neck. However, separate fingerboards in maple and rosewood would be introduced a few years later.

The pickup that Fender designed for the instrument was revolutionary as well. Unlike earlier pickup designs, which featured a single large magnet, it had six individual pole pieces, one for each string. Furthermore, it was housed in a metal assembly that had three individual bridge saddles—two for each string. This saddle design allowed players a much greater degree of control over individual string height and intonation than had been possible with traditional bridge designs. Intonation still required some degree of compromise, as two strings shared a single bridge, but those chunky metal bridges also imparted a lot of sustain and what we now think of as the classic Telecaster tone.

“Leo used some of the [pickup] designs that he used on his [Hawaiian] steel guitars,” Fullerton recalls. “We made prototypes with different sized wires and magnets and experimented with the placement of the magnets and the bridge plate. All these things made different sounds.”

By 1949, Fender and Fullerton had completed a prototype. The instrument looks remarkably like the classic Telecaster so well known today. The body shape is there, as is Fender’s patented bridge/pickup assembly. One striking difference, however, is the headstock, three-on-a-side “snakehead” design that is closer to Leo’s earlier lap steels than the soon to be distinctive six-on-a side Fender peghead. In what was to become a Fender tradition, Leo and George Fullerton placed this prototype in the hands of several working guitarists in the area, including country guitarists Jimmy Bryant and Roy Watkins, inviting their commentary and design input.

In 1950, Fender was ready to go to market with his new guitar. The single-pickup Fender Esquire was introduced that year with a list price of $139.95. Aside from a few small differences—including the absence of a truss rod or string retainers—it was essentially the instrument we know today as the Telecaster. The prototype’s “snakehead” headstock had been replaced by the distinctive six-on-a-side Tele headstock that is still a familiar feature of the guitar. According to one story, Fender’s headstock design was inspired by stringed instruments played by Croatian musicians who were performing in California. Another story suggests that he was influenced by the six-on-a-side machine head on the custom guitars that Paul Bigsby built for Merle Travis.

Apparently, Leo had envisioned the Esquire as a two-pickup instrument all along. But Fender's distribution company at the time, Radio and Television Equipment Company (RETC), was eager to go to market with this novel new guitar and brought out the single-pickup Esquire before Leo had time to perfect a neck pickup for it. Two-pickup versions of the Esquire followed shortly thereafter, but they were produced in small quantities for a short period. Today, they are fairly rare, and sought after by collectors.

Later in 1950, the instrument underwent the first of several name changes. The two-pickup Fender Broadcaster was introduced in the fall of that year at a list price of $169.95. This is the instrument that claims the title of the world’s first mass-produced solidbody electric guitar—although guitar historian A.R. Duchossoir places the total production run at somewhere between 50 and 500. In those days before rock and roll, the electric guitar market was still a very small business.

In 1951, the Gretsch company requested that Fender drop the name Broadcaster. Gretsch had been manufacturing a line of drums called the Broadkaster Series and, despite the difference in spelling, claimed the right to use that name. A pragmatic man who had witnessed shortages of building materials during the second World War—not to mention the Korean War, which was then underway—Leo Fender simply snipped the word Broadcaster from the headstock decals, and for a while the instrument came out bearing the Fender brand name but no model name. These have subsequently dubbed “No-casters.” Not many guitars came out this way, and like the two-pickup Esquires, they are rare.

In 1951, the Fender Telecaster was officially introduced, at a list price of $189.50. The Esquire continued to be produced as an affordable single-pickup alternative, listing at $149.50. The Telecaster name had been inspired by a brand-new invention of the day: television. The guitar’s impact on popular culture would prove to be nearly as profound as that of the small screen.

Many Fender guitars followed in the wake of the Telecaster, starting with the Stratocaster in 1954, but none have ever been able to supplant it. In a sense, all solidbody electric guitars are a footnote to the Telecaster. Telecasters made between 1950 and 1954 are particularly desirable today and are notable for their black pickguards. (Fender switched to white in 1956.) Thus, these early models are known as “blackguard” Telecasters.

Down through the years, just about everything that can be done to a guitar has done been done to the Telecaster, in efforts to modify or improve it. It has been manufactured with all manner of different pickups, materials and hardware. It became a hollowbody guitar at one point, a variant that is still popular today as the Thinline Tele. Yet, somehow, the Telecaster never lost its essential identity.

The Telecaster has had a role in just about every form of popular music that involves electric guitars. The bright sound of the bridge pickup made it ideal for chicken-pickin’ country leads, while the neck pickup was long considered the closest an electric guitar could come to the woody warmth of a strummed acoustic rhythm. Guitarist Luther Perkins’ reverby, deep-talkin’, muted string patterns created the signature chugging propulsion for early Johnny Cash hits like “I Walk the Line” and “Ring of Fire.” Country great Buck Owens and his lead guitar player Don Rich both played Telecasters, forging the classic “Bakersfield sound” of the early Sixties. Country icons like Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings have all been conspicuous Tele men, a tradition that continues today with noted pickers like Vince Gill, Albert Lee, Pete Anderson and Brad Paisley.

But the Telecaster has been a significant force in the blues as well. In the Forties, Muddy Waters made the pilgrimage from rural Mississippi to urban Chicago. Somewhere along the way he traded his acoustic guitar for an electric and forged a whole new blues idiom—amped up, gritty and citified. The Telecaster’s clear, high tone was a key ingredient in Muddy’s shiver-inducing electric slide work, which was often performed with a capo on the neck of his late-Fifties red Tele. And while B.B. King is most closely associated with “Lucille,” his Gibson ES-335, he played a Fifties Esquire earlier in his career, back when he was still known as “Blues Boy” King. Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown played a Tele in the early Fifties, and this inspired the legendary Albert Collins to purchase a Fender Esquire in 1952. He’d moved on to a Tele by the time his first single, “The Freeze”/“Collins Shuffle,” came out in 1958, and he stayed with Telecasters throughout his life and career. His use of the instrument was particularly unique, revolving around an open F minor tuning and the use of a capo on the seventh or eighth fret. Collins also fingerpicked rather than use a plectrum. For much of his career, he used a 1966 Telecaster Custom, which later became the basis for Fender’s Albert Collins signature model Tele in the early Nineties.

Of course, the Telecaster was born just in time for rock and roll’s arrival and played an important role in the formation of this new sound. Guitarist Paul Burlison’s Esquire laid down some fundamental rockabilly riffs with the Johnny Burnette Rock ’n Roll Trio, influencing young Britons like Jeff Beck. Nathaniel Douglas played Telecaster in Little Richard’s backing group, performing on some important dates, including his electrifying performance in the seminal 1956 rock and roll film The Girl Can’t Help It. Guitar great James Burton started out on a Telecaster in 1952 and later used the instrument on Dale Hawkins’ essential single “Susie Q.” As lead guitarist for Ricky Nelson, Burton brought his Tele into America’s living rooms during the late Fifties as part of Nelson’s weekly musical spot on The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet TV show. A 1969 paisley Tele became Burton’s signature instrument during his early Seventies tenure with Elvis Presley and beyond, later forming the basis for Fender’s James Burton signature model Telecaster.

Rock and roll influenced the Telecaster just as much as the Telecaster influenced rock and roll. In 1956, Fender introduced bold custom colors, like Fiesta Red and Lake Placid Blue, that were designed to appeal to the wild new youth audience that rock and roll inspired to take up the electric guitar. In 1959, the company brought out the Telecaster and Esquire Custom models, classy axes with sunburst finishes and white binding.

Sonically speaking, the Telecaster proved an extremely adaptable instrument as rock moved into the psychedelic Sixties. During his time with the Yardbirds, from 1965 to 1966, Jeff Beck produced some of the most astounding and influential tones ever to come out of a Fender Esquire. That bright bridge pickup, which had been so great for rootsy country sounds, proved equally adept at generating droning, psychedelic, sitarlike overtones when goosed by a fuzz tone and pumped hard through Beck’s twin Vox AC-30s. The sound energized key Yardbirds tracks like “I'm a Man,” “Over Under Sideways Down,” “Heart Full of Soul,” “Train Kept a Rollin’ ” and “You're a Better Man Than I.”

Beck’s Esquire work on these records set the stage for the heavy late-Sixties rock of Cream, the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Led Zeppelin. Eric Clapton, Beck’s predecessor in the Yardbirds, also played a Telecaster during his tenure with that group. And Beck’s successor in the Yardbirds, one Jimmy Page, made extensive use of Telecasters when he founded Led Zeppelin after leaving the Yardbirds in 1968. The Tele sound figures prominently on the first Led Zeppelin album, and Page later used a Telecaster for his solo on “Stairway to Heaven.” During the late Sixties, Page was often seen with a Tele bearing a vivid custom psychedelic paintjob, a piece of artwork that lasted until a Led Zep roadie later took it upon himself to refinish the guitar without Page’s knowledge or permission—and much to the guitarist’s horror.

But the Sixties weren’t all about feedback and fuzz tones. Steve Cropper created a much-imitated R&B Tele style during his years as a session man for Stax Records and lead guitarist for Booker T and the MGs. Cropper’s plaintive sound—built around inverted thirds and other intervals played on the G and high E strings—proved the ideal backdrop for the soul vocal stylings of Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. Meanwhile, seminal country rock guitarist Clarence White came up with one of the most significant Telecaster modifications to originate outside Fender: the White/Parsons B-Bender. Fitted into the bridge and operated by a lever located on the strap peg, the device could be used to dip the pitch of the B string a whole step, thus imitating the mournful sound of a pedal-steel guitar. That tone was integral to the invention of the country rock genre on albums like the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo and throughout the work of the Flying Burrito Brothers and Graham Parsons.

In 1968, Fender created a particularly elegant, all-rosewood Telecaster for George Harrison. It was presented to the guitarist as sessions for the Beatles’ Let It Be album got underway. The guitar can be seen in the film of the same name that documented the sessions. Harrison also played it during the Beatles’ final public performance, on the roof of the quartet’s Apple office, on January 30, 1969. Shortly after, the Rosewood Telecaster was added to Fender’s regular guitar line. Listing at $375, it had the distinction at the time of being the most expensive Telecaster ever. It was also one of the heaviest Telecasters ever produced and difficult to wear on a shoulder strap for prolonged periods. This shortcoming is rectified by the new Tele-bration Series Lite Rosewood Telecaster, which employs a dark-stained spruce body core between a rosewood top and back for a lighter overall weight.

By the time the Beatles gave that final, historic rooftop performance, major changes had taken place at Fender. On January 5, 1965, Leo Fender had completed the sale of his company to CBS for $13.5 million, a record sum at the time. Until then, Fender had been a fairly small operation—so much so that avid Fender historians know the names of individual assembly-line workers who wound pickups, routed bodies and performed other work. Under CBS, however, Fender grew to be a massive manufacturing enterprise. But as the production figures went up, there was an inevitable decline in quality. As a result, pre-CBS Telecasters, from 1951 to 1965, became highly sought after.

But it should be remembered that Telecasters and other Fender guitars didn’t just change upon the arrival of CBS. Many manufacturing techniques instituted by Leo Fender stayed in place for years after the CBS takeover, and as a result many mid-Sixties Teles are comparable to their pre-CBS counterparts. The turning point is generally regarded as 1967, when the Telecaster’s tone control wiring underwent some significant changes.

Setting aside the quality issue for a moment, CBS did what large corporations tend to do—they sought to diversify the Fender line, which created many interesting Telecaster models, such as the aforementioned Rosewood Tele. In 1967, Telecasters were offered with an optional Bigsby tailpiece for the first time, and 1968 saw the advent of the Thinline Tele, a unique hollowbody version of the classic Telecaster design that found favor with many players, particularly in country.

Humbucking pickups began making their appearance as a stock Telecaster option in 1972. But by this point, humbuckers had already become a popular custom modification, performed by guitar shops and amateurs gaining their first experience in the use of a router. Humbucker-retrofitted Teles became a signature instrument for Keith Richards in the early Seventies, and the Telecaster tone seemed to lend itself especially well to his distinctive five-string, open G tuning. An early Fifties Tele the guitarist calls Micawber—after a character in Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield—is one of Richards’ most beloved guitars.

Emerging in the Seventies as a promising young songwriter, Bruce Springsteen was rarely seen without his trademark Esquire. Long regarded as a workingman's guitar, the instrument fit perfectly with the Boss’ proletarian persona. The Tele’s blue-collar heritage was accentuated when it was adopted by punk rockers like the Clash’s Joe Strummer in the late Seventies. Continuing in the tradition of socially conscious folksinger Woody Guthrie, Strummer emblazoned his Teles with political slogans. Combining the trebly cut of reggae with the ragged roar of roughhouse rock and roll, Strummer’s rhythm guitar style was particularly suited to the Telecaster. During the new wave era that followed in punk’s wake, noted players like Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders and Andy Summers of the Police also favored Telecasters. Summers’ sunburst 1961 Tele with white binding is particularly iconic.

The seeds of the Telecaster’s continuing popularity in our own era were sown at the dawn of the Eighties, when executives Bill Schultz and John McLaren joined CBS/Fender in a major management reshuffle at the company. As part of their drive for improved quality control, they sought to revive Fender’s glorious past. This was reflected in Fender’s Vintage Reissue series, including the Vintage ’52 Telecaster in 1982, and continued to be a dominant theme after Schultz and a consortium of investors bought Fender from CBS in 1985. The American Standard Tele, with its blend of vintage style and a few tastefully deployed modern features, was introduced in 1988. Fender’s Custom Shop, first established in 1987, came up with a 40th Anniversary Telecaster in 1991. The Nineties also saw the start of Fender’s Signature Series Teles, with James Burton, Albert Collins, Danny Gatton, Jerry Donahue, Waylon Jennings and Robben Ford, among others—including Slayer’s Kerry King and Burzum’s Varg Vikernes—all being honored with signature models.

While cultivating a vintage sensibility and sense of pride in the Tele's history, Fender simultaneously strove to keep the guitar current, introducing instruments like the Lace Sensor–equipped Tele Plus and the Set Neck Tele that John Page designed for the company in the early Nineties. In both its modern and vintage forms, the Telecaster has found favor with current players like Tom Morello, Radiohead’s Tom Yorke, Jon Greenwood and Ed O’Brien and John 5, who was worked with artists across a range of styles, from Marilyn Manson to Avril Lavigne to Lynyrd Skynyrd to k.d. lang. Fender marketing over the past 20 or so years has always striven to maintain a balance between vintage Tele fiends and Tele modernists.

“I signed John 5 as a Fender signature artist at a time when I was feeling like Fender really needed something new,” says Rich McDonald. “We were a little too centered on the country and blues side, so I started sniffing around. And when I started looking for that new face of the Telecaster, I ran smack dab into John. He is the kind of quintessential player who reflects the versatility of the instrument. He’s gonna blow country stuff onstage with k.d. lang or as a session guy or in his own solo work, but then he’s gonna do the heaviest stuff in the world with Marilyn Manson and Rob Zombie. And he does it all on a Telecaster.

Fender history entered a new era with the ascension of Larry Thomas as CEO in 2010. For the first time ever, Fender is now in the hands of a passionate guitar player and collector who has also amassed considerable retail and marketing experience as the longtime head of Guitar Center.

“Larry’s been a real breath of fresh air,” McDonald says. “It’s unbelievable to have such a guitar-centric CEO running this company. We’ve already built quite a few Telecasters for him personally. He’s just reveling in the anniversary by specking out super-lightweight ‘blackguard’ Teles with really big necks. That’s really his thing. From being in the industry so long, his focus on Telecasters and other Fender products is from a much more personal level than a lot of other guys. Larry was friends with key Fender innovators like [onetime Fender vice president] Forrest White. He’s always been an historian.”

Referencing his own deep collection of Teles and other iconic Fender models, Thomas has refocused manufacturing on classic body weights, specifications and materials. But at the same time he has encouraged his R&D team to let its imagination run wild. The Fender Tele-bration Series is one strong indication of that.

“Back in the old days,” Justin Norvell says, “Fender would put wild design ideas out there and just throw them into the hands of players to see how they responded. We’re getting into more of that approach again. A lot of cool ideas come across benches or desks or out there in the field. Sometimes we just make scribbles on a piece of paper that never come to fruition as an actually design or model. But we’re speeding that process up now and putting some of those ideas on the front burner.”

One instance of this approach is the new Vintage Style Tele bridge with three special intonatable brass saddles, found on the Tele-bration Series Vintage Hot Rod ’52 Telecaster. For years, Telecaster players have had to choose between the classic tone of the traditional three-bridge saddles, each supporting two strings, and the superior intonation offered by the six individual saddles found on many post-CBS Teles.

“That’s the great compromise that every Tele player has to face,” Norvell says. “ ‘Do I go for tone and stick with the brass saddles, or do I go for the intonation with six adjustable saddles?’ Every Tele player walks up to this decision point. There had been compensated saddles in the past, which kind of split the difference a little bit, but not perfectly. But one of our R&D guys, George Blanda, was messing around with this concept he had: a free-floating, notched piece that would kind of homogeneously connect with the brass and keep the sound going, but also enabled the piece to move, for better intonation adjustment. So while he was working on that, we were thinking of this Tele-bration Series. Now we’ve rolled that bridge out on the Vintage Hot Rod Tele, which has a mini-humbucker pickup.”

And so the quest goes on…perhaps forever. In our digitized, dystopian era of overnight obsolescence, it is nothing short of amazing that people are still tweaking, geeking out over and totally loving something that was invented more than 60 years ago. But then what better 60th anniversary compliment could anyone offer than to say “You still fascinate me. I still desire you. I still wanna mess around with you”?

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“What blew me away was that everyone wanted the curly maple top. People were calling, saying, ‘I’ve got to have the bird inlays’”: Paul Reed Smith on raising the Standard 24, finally cracking the noise-free guitar and why John Sykes is a tone hero

“It combines unique aesthetics with modern playability and impressive tone, creating a Firebird unlike any I’ve had the pleasure of playing before”: Gibson Firebird Platypus review

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)