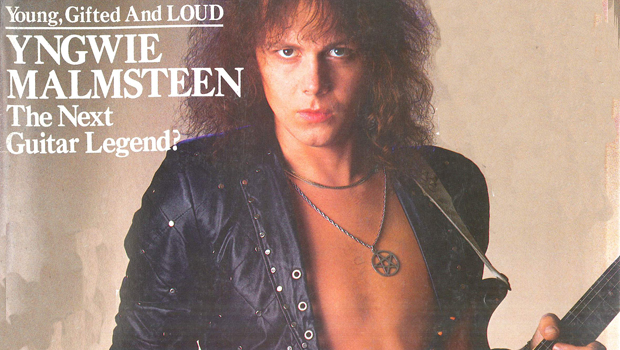

Yngwie Malmsteen Discusses his Roots, His Rep and his Latest Album in this 1986 Guitar World Interview

Here's our interview with Yngwie Malmsteen from the January 1986 issue of Guitar World. The original story ran with the headline "Like Him or Not, He Demands Your Attention" and started on page 24.

Either you love him or hate him -– that’s the way it is with Yngwie Malmsteen. Either way, it doesn’t phase him.

“I’d rather have people dislike my style than change it,” he says. “If someone says, ‘Hey, Yngwie, you play too damn much’ –- I don’t care. They way I play is the way I like to play. If people like it – great. If they don’t, it’s still fine with me.”

“I want to say something very clearly. I understand that I’m a self-confident person who might come off with the wrong attitude sometimes, but I don’t mean to. I just believe in certain things and I know exactly what I want. I’ve always sacrificed things in order to become the best musician I could be. My will power has always been very strong. If I want something, I’ll get it. I’ve had no trouble keeping my head on my shoulders,” and, he adds angrily, “nor do I have any chips on there.”

That last comment is a reference to the story contributing editor Steven Rosen did in Guitar World in the July 1984 issue. The title was “The God With The Chip On His Shoulder,” and Malmsteen is upset about it. “That’s not the way I am,” he says.

“That story described me as being a big-headed guy who sucks up attention, which is totally wrong. The biggest mistake people make about me is that they see me as some sort of God-like figure with a big ego. If I see a button a T-shirt that says ‘Yngwie is God,’ I just look at it as a complimentary way of people telling me they like me. Although it’s very flattering, it doesn’t change the way I look at myself. I’m just a normal person completely devoted to my art as a guitarist and musician.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That confidence and singularity of vision are precisely why he has become so musically accomplished today. Since emigrating from his native Sweden in February 1983, Malmsteen has become the fastest rising -– and most controversial –- guitarist of the eighties. Much of the bad press he’s received can be attributed more to a lack of understanding his intentions than to his so-called ego.

It’s not the ego, folks, it’s rock and roll careerism. Malmsteen’s sole objective has always been the advancement of Yngwie Malmsteen. He used the two previous bands he was in, Steeler and Alcatrazz, merely as stepping stones to return to the Rising Force project he initiated in Sweden seven years ago.

"I wanted to leave Alcatrazz a lot sooner than I actually left," says Malmsteen, who stayed in the band for nearly a year and a half and in Steeler for just four months. "There was always a subliminal disliking between me and the rest of the guys in the band. We couldn't agree upon things and my influences and beliefs were totally different from theirs. We tried to be as nice as we could to one another, but it was an uncomfortable atmosphere. They probably feel the same way about me."

Maybe so, but you can be sure Malmsteen's former band members are not knocking his staggeringly unconventional playing style or his rapid ascension toward the top of the guitar world. What made Malmsteen so successful so fast? A total obsession with the instrument and a craving to develop a style quite unlike his contemporaries-that's what. " If guitar players just listen to other guitar players it's almost impossible to avoid sounding like them," says Malmsteen, who acknowledges only Jimi Hendrix and Ritchie Blackmore as guitar influences. "I try to achieve a style that is a lot different from what other guitarists sound like. If you listen to other instruments like violin, flutes or keyboards you will break away from the clichés of guitar playing."

Malmsteen, as you know, is most influenced by classical music, especially the unorthodox work of violin virtuoso Niccolo Paganini and the more sedate compositions of J.S. Bach. "Classical is the peak of the development of music," says the guitarist, "and Bach is the most influential classical composer of all. Beethoven, Chopin and Liszt all took from Bach. Mozart even took from Bach; he was a little kid when Bach died. Classical is the source of music; it's like a religion, almost.

"Paganini is probably my biggest classical influence. I got turned on to him through a tv show in Sweden. This guy was playing Paganini and I freaked, so I went out and bought Paganini's "Twenty-Four Caprices," which is my all-time favorite thing to listen to. Paganini did with his instrument what few people have ever come close to doing. He was a rock and roller -- very wild and very extreme."

Extreme is one of the many words used to describe Malmsteen's guitar style-an ear-searing combination of heavy metal bombast and classical beauty. Although this approach is readily apparent on most of his recorded work, it was the Rising Force album which gave Malmsteen's career a quick boost right after leaving Alcatrazz. Originally released only in Japan on Polygram, the album sold so many copies as an import that U.S. Polygram went on to release it ... a good move. At its peak the album went as high as number 60 on the Billboard chart-an uncommon achievement for a predominantly instrumental album with no airplay.

Malmsteen also played bass on the album - a Fender Telecaster bass with a tremolo. "The bass parts are pretty straightforward," he says, "so after a while I got bored. I could have played very technical and complex if I wanted to, but I didn't think fancy bass playing would have sounded good. I did a few cool–sounding runs, though."

Malmsteen turned the bass chores over to Marcel Jacob on the recently released

Marching Out

, where the emphasis is more on songs than flash. Apart from a couple of guitar arias ("Overture 1383" and the title track), the album is comprised of hard-hitting rock and roll-material which may come as a bit of a shock to those fans familiar only with Malmsteen's more adventurous

Rising Force

album. Marching Out is heavy enough to satisfy metal fans, but Malmsteen's presence makes the album more than just a typical slugfest. The first thing you notice about his solos, aside from their pronounced classical influence, is Malmsteen's unusually fast technique his trademark.

What is it about playing fast that appeals to Malmsteen?

"lt's not playing fast in itself that appeals to me," he says. "Speed can be very dramatic if you do it together with playing slow-it's a great contrast. It's also important to me that what I play fast will also sound good if the same notes are played at a slower speed. The reason I concentrate mostly on fast licks is because that's what my audience wants to hear, to a certain extent.

"I don't consider myself to be a very fast player. I'm sure there are other guitarists who can play faster: What I do that a lot of other guitarists don't do is I don't play things that are rubbish. If you would slow down the fast licks that a Iot of other guitarists do, people would puke. I play classical runs, arpeggios and broken chords that if played at a slower speed would sound very nice as well. But if you do it very fast and very clean, but not necessarily as fast as someone else, you will appear much faster because what you're playing actually makes more sense.

"I developed a fast technique simply because I didn't want to be limited. I was obsessed with the fact of always improving. Just because I would play a certain thing in a particular way one day, it doesn't mean I couldn't improvise and play it better the very next day. I approached the guitar that way for a real long time."

Here's how Malmsteen developed his technique: "I had two cassette decks that I used to tape my music on-one at the rehearsal studio and one at home. The one at the rehearsal studio was slower than the one at home. So when I went home and listened back to the tape I recorded at rehearsals, my guitar sounded so much faster than I actually played it. I said 'Wow -- I can't believe how fast I sound.' And since my goal was to improve on everything I would play the day before, I developed a lot of speed and I began playing faster and faster and faster. It's a weird story, but it's the truth.”

Anyone who's witnessed Malmsteen on stage knows he is an intensely exciting performer. Most guitarists with mind-boggling technique are actually quite boring in concert, but Malmsteen manages to impress as well as entertain. He is always in constant motion, whether playing his Strat with his teeth or effortlessly twirling it around his body.

"When I play a song at rehearsals I often get bored with it," he says. "As soon as I get in front of an audience I get excited and everything comes alive. This is because I'm not just playing for myself. I live for my audience-they're everything. It's the best feeling in the world to go on stage and have the crowd love you. As long as there's an audience, I'll never lose a desire to play."

Malmsteen and his band Rising Force continue to be lumped into the metal genre. Does it bother him? "I don't care if people call our music heavy shit or heavy metal," he says. "Onstage we're definitely metal because we're just as heavy as the headbangers could ever want it. But what we play is a lot more sophisticated than what those run-of-the-mill metal bands are doing. Besides, I don't think my guitar playing sounds like anyone else."

Much hard work, of course, has gone into honing his style. "I 've been playing constantly since the age of eight," says the twenty-two-year-old guitarist, who first picked up the instrument after seeing Jimi Hendrix on TV the day he died, September 18, 1970. "Hendrix inspired me to play, but I'm actually not that musically influenced by him. I loved his image more than anything. He looked really cool onstage and was a fantastic performer."

Malmsteen started playing on a cheap acoustic from Poland that his mom had given him: "I taught myself how to play it. I bought a pickup for sixty cents in a mail order catalog. I put it on the acoustic and played through an old tube radio. I cranked it up and. it sounded real heavy."

He acquired his first electric guitar, a Clear Sound, at the age of nine from his brother. "It looked like a left-handed Strat," says Malmsteen, "and it had a great neck. I even put an extra fret on it. As soon as I started sounding decent, I played to what was on the radio. But I never practiced in a traditional sense-not at all. I never sat down and played the same licks over and over. From the very beginning, from the very first day I picked up a guitar, I was improvising and just creating music. I have perfect pitch, so I figured everything out just by listening. I played a real lot - up to nine hours a day - only because I wanted to keep getting better and better.

"My family was very musical," he adds. "My sister played flute and piano and my brother played many instruments - guitar, drums, piano, violin and accordion. My father even played guitar, but I didn't grow up with him; he and my mother got divorced when I was a baby."

It was Malmsteen's mother, the only non-musician of the family, who decided to name her son Yngwie: "She once had a crush on this guy in her class named Yngwie and she named me after him. It's a very old name; it means young Viking chief."

Malmsteen was a young warrior during his school years, too. "I was a bad boy," he says. "When I was fourteen I drove my motorbike inside the school. I used to fight a lot and I rarely did my homework - I played guitar instead. I'm a lot less wild now. In school I got easily frustrated, especially with people who didn't show a lot of intelligence. Fights would start whenever I told someone how stupid they were.

"The only reason I didn't do my homework was because I didn't want to. I had the highest grades in the subjects I was interested in-art, woodwork and English-the other subjects I just didn't care about. I would never let anyone tell me what to do."

He quit school at the age of fifteen and got a job repairing guitars at a music shop in Stockholm. While working there Malmsteen got the idea to scallop guitar necks. "A lute came in from the 1600s," he recalls. "Instead of having frets, the wood was carved out on the neck, so the top of the wood was the fret. It looked really cool, so I thought it would be an interesting idea to do on a guitar neck. I took an old neck and scalloped it out just like the lute neck. It felt a lot better to play on and you could grip the strings a lot better, too.

"I do my own scalloping on all my guitars. But I wouldn't recommend anyone to do their own scalloping unless they're good at woodwork or good at working on guitars. It requires a lot of skill to do it properly and it's quite painstaking. I've been working on guitars for a long time, so I have the experience to do precision work. Besides, ever since I was very young, I've always been handy with wood: I used to build wooden airplanes. I would never let anyone but me scallop my guitars. I have some vintage Strats that aren't scalloped, but I don't play them on stage."

Malmsteen played guitar so much, in fact, that he based his life around it. "I had to go to the army when I was eighteen," he explains, "but I only stayed for two days. They made me take all kinds of tests. When they realized I had a high I.Q. they wanted me to be an officer, but I didn't want to. They didn't want to let me go, but I acted very insane to them. I told them I could never get along with my mother, I never worked a day in my life and I never used to go to school. All I did was play guitar all day long. There were plenty of guns there, so I made a threat. I told them I would shoot myself if they didn't let me go, and they fell for it."

Malmsteen was getting frustrated with the music scene in Sweden at this time. He wanted to make it desperately, but, since the music he was playing wasn't very commercial, the record companies didn't want to deal with it. Fortunately, Malmsteen wrote three singles that eventually attracted the attention of Swedish CBS. "They were all set to release them but never did," he says. "It really pissed me off."

For some strange reason, however, a demo of the songs made it to the San Francisco area. "I don't know how it got there," says Malmsteen. "It was being played on college radio stations before I ever came to the States." Mike Varney, noted heavy metal connoisseur and head of Shrapnel Records in California, heard it and was immediately impressed with the young Swede's unusual style. "Mike got in touch with me and asked me to come to the States to do an album for his label," says Malmsteen, who made his American debut on the Steeler album. "He believed in me and helped me out, especially when I first went to California. But I still would have come to the States anyway -- I was so dissatisfied with the music scene in Sweden I knew I had to leave.

"I considered working with Phil Mogg of UFO, but it was all talk, really. Then I met Alcatrazz' manager Andy Trueman and he was right on the money. He said, 'You want a job, you got it.' It was definitely the right move. He's my manager now; we get along well and we're a good team."

Malmsteen appears on two Alcatrazz albums -- No Parole From Rock 'N' Roll and Live Sentence. What does he think of their latest release, Disturbing The Peace? "It's an interesting change," he says. "It sounds so different than when I was in the band, so you shouldn't compare them. The music they're playing now doesn't even have a hint of classical music; it has a lot of strange Frank Zappa funk-jazz melodies."

The Zappa influence, of course, comes mainly from Steve Vai, who was a guitarist in Frank Zappa's band before joining Alcatrazz. "He plays the kind of music he plays very well," says Malmsteen, "but I'm not particularly fond of the melody lines he writes. I've always extremely disliked anything that resembles jazz. I'm a purist for classical music."

Unlike a classically-influenced rock guitarist like Michael Schenker, Malmsteen has applied a classical approach in a more radical manner. "Schenker often injects his playing with classical sounds," says Malmsteen, "but in between he's playing all this pentatonic stuff. I'm going all the way with it and I'm trying to put the classical parts in very aggressive and unusual contexts. That's what I tried to do on Marching Out."

Malmsteen produced both the Marching Out and Rising Force albums. "I've always been aware of recording techniques," he says, "and I've always felt I could do a better job than an outside producer because they obviously don't know the song as well as I do. I mean, I don't think a painter would do the background and let someone else finish the rest of the painting. I want to write the songs, produce them and control it until the record is in the stores and 'on the turntable."

But doesn't Malmsteen find it difficult to be objective of his own material? "No," he says bluntly. "Rising Force was meant to be a guitar album, so I purposely wanted the guitar parts to be more prominent. Marching Out is more song-oriented; it doesn't sound as if a guitar player did the production. It sounds very even. You can hear all the instruments very clearly and my solos aren't too loud or too long. I will always produce my records from now on. It's a more controlled atmosphere than playing live, but it's very challenging."

Malmsteen's desire to do it all obviously puts a lot of weight on his shoulders. Will he keep a clean head and progress? Or will he get caught up in the rabid attention he's been getting and stagnate? The answers to these questions will prove if Malmsteen becomes the legendary guitarist he is so capable of becoming.

Yngwie Malmsteen has come a long way in the short time he's been in America, but his most important years will be his next.

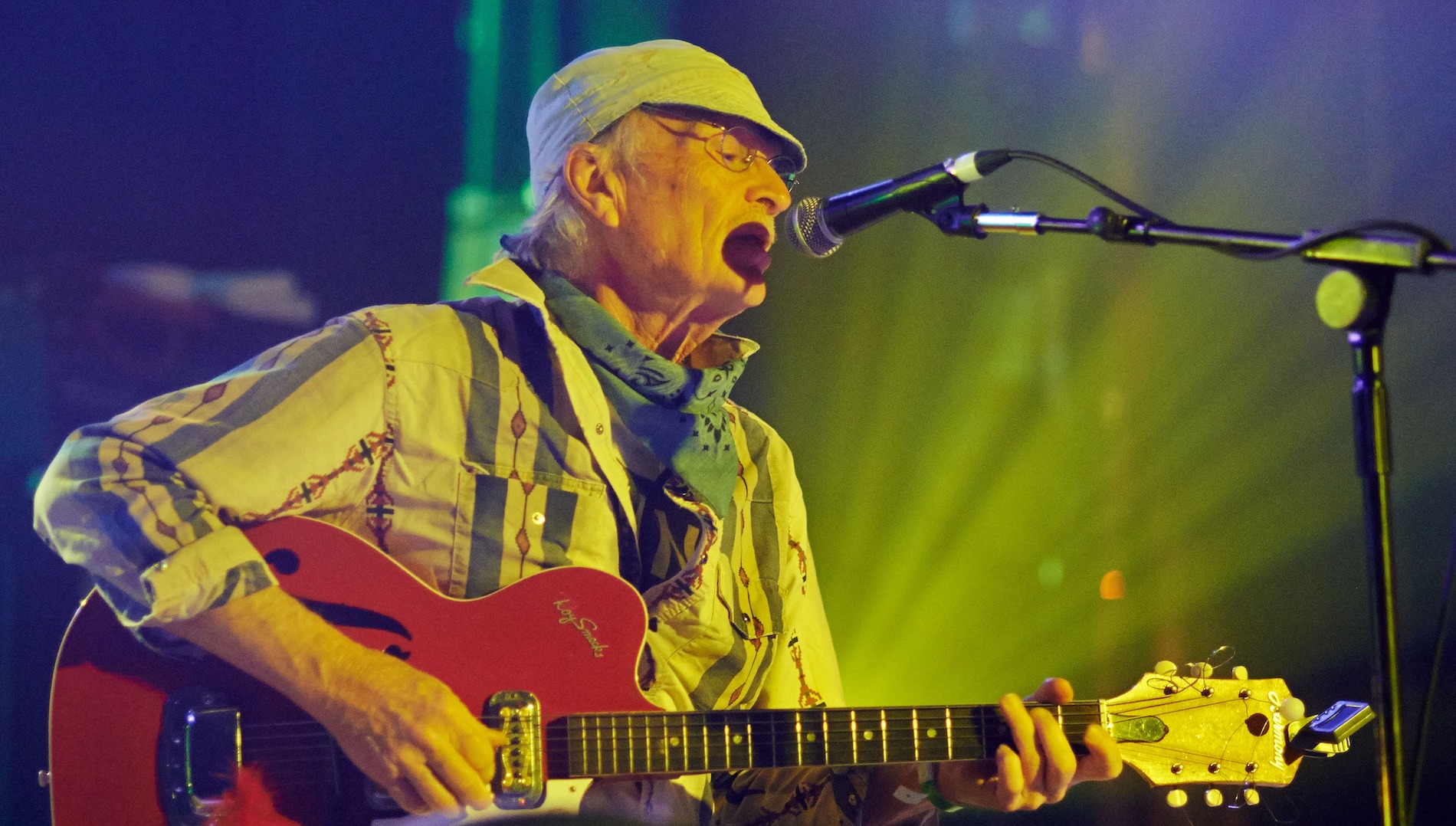

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83

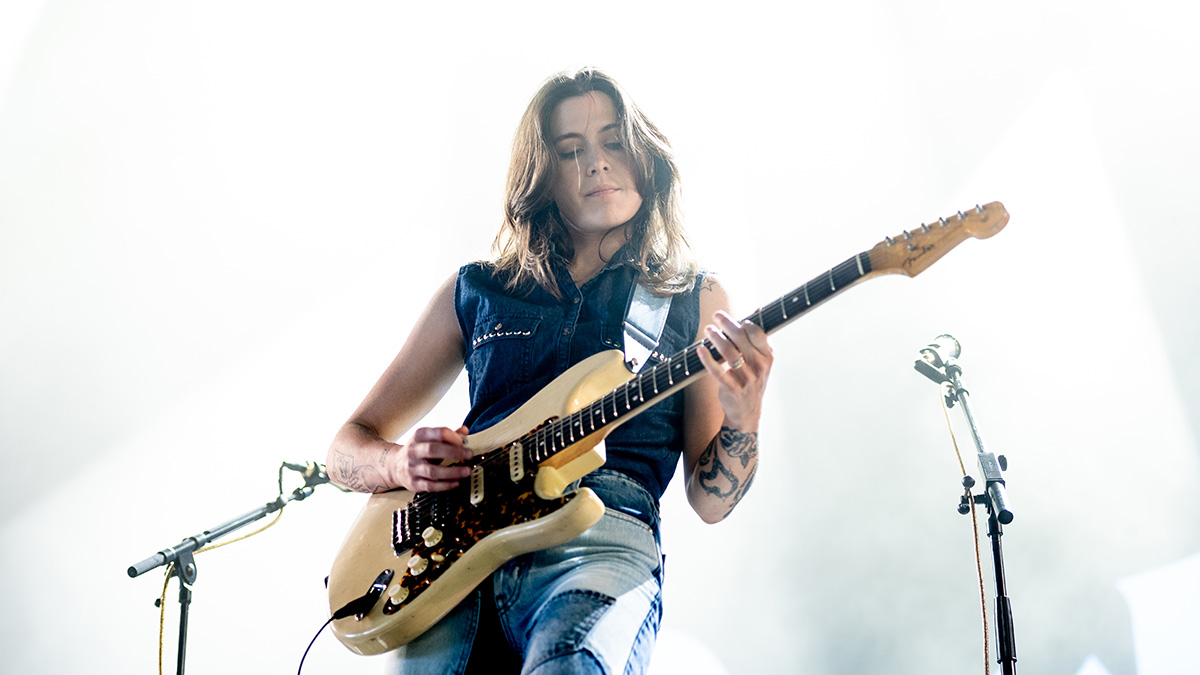

“The future is pretty bright”: Norman's Rare Guitars has unearthed another future blues great – and the 15-year-old guitar star has already jammed with Michael Lemmo