Jimmy Eat World's Jim Adkins: "I used to study classical and jazz... then I was suddenly sleeping on floors and playing punk-rock"

The founding frontman shares wisdom gained from a career spanning nearly three decades - and explains why he can't tear himself away from heavy-gauge strings

As the founding frontman of Jimmy Eat World, Jim Adkins has learned a thing or two about the sounds he’s looking for - both creatively and tonally.

Big chords and big choruses have been his trade since their formation in 1993, the Arizonan quartet breaking into the mainstream with fourth full-length Bleed American in 2001 and becoming hugely influential on waves of bands to come.

Beneath the biting punk rock guitars and crowd-conquering melodies, there’s been a dependable honesty to the music that has served them well over the years, up to and including newest effort Surviving. As their singer/guitarist explains, the key to that survival is following their hearts, not their heads…

“When you’re writing, there’s a line you have to walk that’s being present but also turning off your inner-self critic,” says Adkins, in a way that’s every bit as sincere and transparent as his lyrics would have you believe.

“If that inner voice gets too loud, you’re not going to get anything done - you will just be distracted by this judgement on how much you suck. But you still need to be present to choose your next response, it’s like totally letting go of future-tripping and choosing to respond in real-time…”

The Jimmy Eat World leader’s points on the technique side of guitar are equally as philosophical, advising players to keep a more panoramic of their own development in face of whatever challenge lies ahead of them.

He’s found improvement can only come through perseverance, but a moment’s pause to reflect on the journey thus far can often help. Context is everything.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In my teenage years, I would come home from school and play for four hours every day at least! That wasn’t even out of ambition; it was because the guitar was so freeing

“Do you remember the physical awkwardness of fretting a note for the first time?” laughs Adkins. “It’s easy to forget guitar is not as easy as piano, where you sit down and go ‘dink, dink, dink’.

"You have to get over the awkwardness of guitar, it can throw you, but if you stay happy with incremental progress, you will get to a place where you can make things that you think are awesome.”

What instruments are we hearing on the new album?

“You’re almost exclusively hearing me play my Fender signature Tele... the JA-90 as they’ve chosen to call it! Using that was important to me. I know there are some people - I’m not going to mention names - that lend their likeness and endorsement to a student-level version of an instrument that they would never play.

"They’re probably thinking they’re going to make a whole lot of money out of it because it’s cheap. Then there’s the other side, where people go so crazy and custom, it hits a price point that no one can afford to buy. Some $8,000 guitar with mother of pearls, gilded parts, all these customized extras that don’t matter in the grand scheme of things.

"I wanted something I could play that sounded great and didn’t come with a bunch of crap that doesn’t matter. What you hear on the record is exactly what you can pick up off the shelves at any guitar store, except for the 13-gauge strings I use.”

That’s a pretty hefty gauge, Jim!

“Yeah... after playing acoustics for such a long time, anything lower feels so weak! I love the sound of them. Sure, it takes a minute to get used to the heavier gauges, but you’ll never miss the lighter ones once you do. We play a lot of chords mainly, but there is some bendy stuff we do - I guess for us it’s more about the chaos than getting a specific semitone glide or whatever.”

I guess the most important thing about Surviving is how little we actually used

When did you realize Thinlines worked best for you?

“When my back started hurting from years of playing Les Pauls (laughs)! I think they look cool. I love the look, the chambered semi-acoustic vibe. It really fits with our music. You can really play up the jangliness - I don’t know if that’s a real word but anyone playing guitar will know what I’m talking about.

"But you can also get more of a stoner saturation if you want to. They’re pretty versatile. I was surprised by the Seymour Duncan SP-90s! I have a Les Paul with mini-buckers in it and these scream more than those. They’re not exactly like old-school P-90s, they’re a little more modern.”

There’s the classic black finish, and then the natural is certainly an eye-catcher…

“We’re actually going into production with an Arctic White version next year, so there’s lots of options. Sorry if this interview is turning into a commercial for my guitar (laughs)! I’m really stoked with it and what you hear is exactly that.”

What kind of fuzz pedals are you using these days?

“There are a couple of different ones I really like. They’re more of the non-editorializing boost type, you know? Just like a bump. The pedals made by JHS and Walrus are totally neutral, there’s one called The Spark [by TC Electronic] that we used a lot. It’s a very subtle thing but just enough to make a difference. Without going down the rabbit hole of A/Bing a bunch of other crap, you can put one of those in line and have options.

“I guess the most important thing about Surviving is how little we actually used. We did have tons of pedals with us but most of the sound is guitar straight into amplifier. That’s it, except for the occasional subtle boost and the Metasonix Butt Probe. That pedal has been on every record of ours since it came out! For amps, it’s a mixture of a Marshall 1979 JMP and Axe-FX…”

That’s an interesting choice, considering you had all the analog options…

“Sometimes it feels like you spend so much time sculpting and designing your sound for the live show that it doesn’t sound right trying to replicate it in the analog physical world. I know what sound I want… it’s this so let’s use this! Why recreate the sound if you have it already?”

Your band has evolved through taking risks over the years. What else can guitarists do to get out of their comfort zones?

“I think when you start writing music, there’s a moment in your development where you feel like you are discovering your own voice. What’s important, and it’s something that people might not think about, is that you start challenging that voice as soon as you find it.

“The worst thing you can do isn’t necessarily coming up with something you don’t like… you can always throw that away, man! The worst thing you can do is come up with something that sounds exactly like you. Why bother making it?

“So challenge that voice as soon as you find it. Try reaching for something just out of reach, just to see if you can get there. You lose nothing by missing the mark.”

How do you find the right hooks for the higher guitar and vocal melodies - is there a method or routine that works for you?

“I don’t really have a set process… it’s a hard question! As long as you are honest with what you put out there, doing something that you like and feel proud of, that’s what matters. Not everyone will agree with you, but the right people will hear it and be able to connect with it.

If you want to get better as a player, look to other styles of playing that aren’t even on your radar

“It might not be an arena rock kind of thing. It doesn’t necessarily have to be. Do you think The National write arena-smashing choruses… but they still play arenas, right?! They put out music that is challenging and rewarding for them and the right people hear it and like it. That’s just how it goes.

"I don’t think anyone has a magic formula for hitting the nail on the head every time. You just have to be honest. I guess just strumming a G chord is not interesting to me. I’m thinking in layers from the start.”

What else do you feel are your signature traits as a player?

“I think a lot of my style comes from my formative years when I was learning to play. I was drilling away on the music I was getting into. I don’t get excited until I hear the melody or phrasing for that top line, sometimes it might not even become the vocal, but I still hear the line there.

"I play octaves a lot - that’s just a side-product of playing so much punk when I was younger. Just learn a NOFX album or any of the stuff John Reis was doing in San Diego around the late 90s or early 2000s.

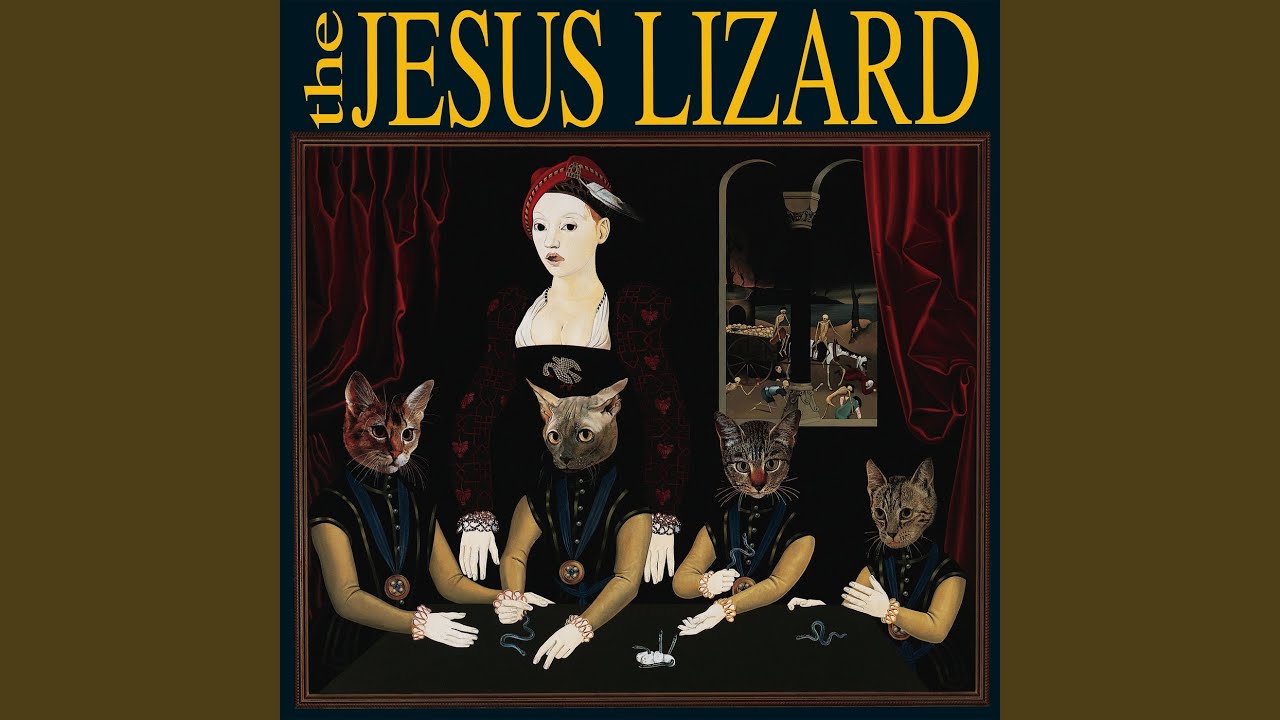

“Duane Denison from The Jesus Lizard was a big influence on me. He was the only guitar player in that band and they didn’t really do overdubs. It’s almost that Van Halen approach. He’s an accomplished technical player, but his choices are almost jazz-inspired.

“It’s not uncommon in jazz to hear people moving around and mimicking rhythms and leads at the same time, like a walking bassline that has a mid or higher melody line on top.

"Gladiator, from the album Liar, has an arpeggio walkdown section that’s a great example of that. There’s a duality between the accompaniment and the hook on top of that.”

Some people might be surprised to hear you’re a jazz fan…

“I used to study classical and jazz for a bit. I kinda quit all that and started playing rock when the band picked up. I was kinda bummed about it too, because it was just starting to make sense [laughs]. Things like scales and substitutions, knowing what options you could throw in over a Gmaj7. It was all just clicking for me and then I was suddenly sleeping on floors and playing punk-rock.

“But wherever you look, you are only going to find yourself. If you want to get better as a player, look to other styles of playing that aren’t even on your radar. And introduce yourself to those methods, because there’s a lot to be said for training your brain that way, stretching into the things you wouldn’t look into primarily.”

Guitars can be such great tools for escapism, in that sense…

“In my teenage years, I would come home from school and play for four hours every day at least! That wasn’t even out of ambition; it was because the guitar was so freeing. I could get lost wherever it took me.

"People might experience this with visual art or other forms like dance, but music had this ‘a-ha’ moment for me when I sat down and realized I was making music. I was like, ‘Wow this sounds like something!’

“It works even if you don’t know what you’re doing! Sit down in front of a piano and starting pushing keys. Sooner or later you will come up with something that sounds cool and you’ll start exploring and getting lost in that no matter what your skill level is. But the more you do it, the higher that skill level gets.

"The same goes for your technical proficiency, which is why these explorations will become quicker in sounding like something real rather than freeform. I love finding that zone where your mind is active but not really directing. You’re listening and responding intuitively. That’s the best. It’s a healthy and sustainable place to recharge… like a deep meditation camp.”

Jimmy Eat World play the UK through July 2020, including Manchester's O2 Academy and London's Brixton Academy, and a headline performance at 2000 Trees Festival.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

Ozzy Osbourne’s solo band has long been a proving ground for metal’s most outstanding players. From Randy Rhoads to Zakk Wylde, via Brad Gillis and Gus G, here are all the players – and nearly players – in the Osbourne saga

“I could be blazing on Instagram, and there'll still be comments like, ‘You'll never be Richie’”: The recent Bon Jovi documentary helped guitarist Phil X win over even more of the band's fans – but he still deals with some naysayers