How adding intervalic leaps can breathe new life into your melodies

Trey Xavier breaks down one of the essential building blocks of all music theory

Hi everyone! My name is Trey Xavier, you may know me from my band In Virtue or as the face of Gear Gods, or from my RelationShapes guitar system. Today I have a couple hot tips on how to break up your scalar-sounding playing for more interesting lines with intervallic leaps.

I’m sure you’ve heard possibly the most famous example of this a million times and not even known it - the intro to Guns ’n Roses’ Sweet Child O’ Mine. You might even have come to despise that lick because of overexposure to it - but there’s a reason people like it so much! It almost completely eschews stepwise (scalar) movement for wide intervals.

I won’t bog this down with too much theory, but the short version is that an interval is the musical distance between any two notes. That’s it! There’s exactly 12 within one octave (because there’s 12 half steps from one note to the next note of the same name) and each one has a distinct flavor and feeling associated with it. I’m gonna list them all here, but don’t feel like you have to memorize them - this is just for reference.

Here they are, in order of size, with the name on the left and the number of half steps (1 half step = 1 fret) between the two notes:

- Minor 2nd - 1 half step

- Major 2nd - 2 half steps

- Minor 3rd - 3 half steps

- Major 3rd - 4 half steps

- Perfect 4th - 5 half steps

- Tritone - 6 half steps

- Perfect 5th - 7 half steps

- Minor 6th - 8 half steps

- Major 6th - 9 half steps

- Minor 7th - 10 half steps

- Major 7th - 11 half steps

- Octave - 12 half steps

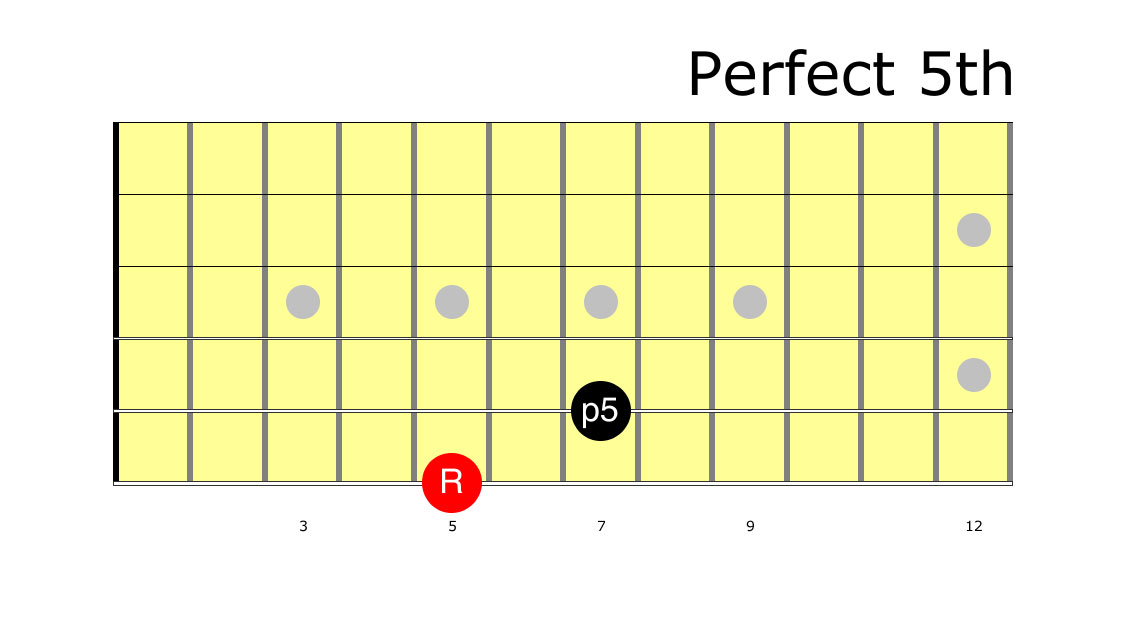

Some of these you already know and use a lot without knowing it - for example, a Perfect 5th is a typical power chord shape:

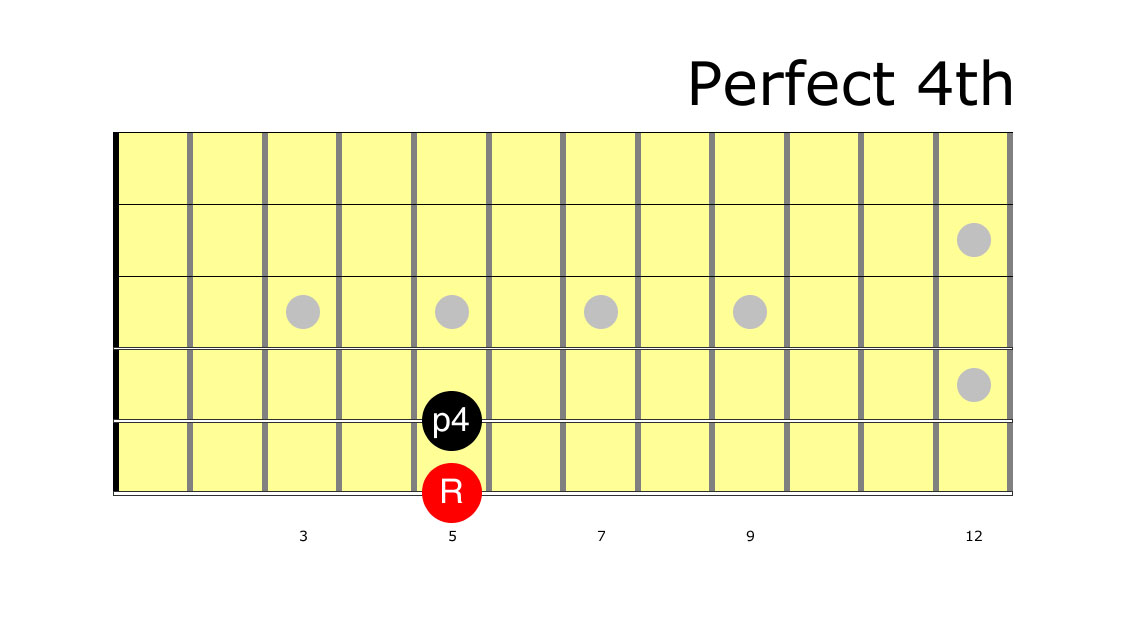

Or if you’ve played Smoke on the Water (the right way), you’ve played Perfect 4ths:

See? That’s already 2 out of the 12 you’re probably an expert at - a full 1/6th of all of them! There’s 2 possible ways to play any interval - harmonically or melodically. Harmonically is when you play them at the same time, like a chord, and melodically is when you play them one at a time, like a melody.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

If you’re used to playing and thinking in terms of scales, don’t worry - you’re not alone and there’s nothing wrong with that. Or, if you don’t really think about anything in particular beyond some shapes that you know, that’s okay too! In fact, scales are made up of intervals too! We’re gonna work with some simple examples to demonstrate the concept, and this will set you on the road to doing this sort of thing on your own.

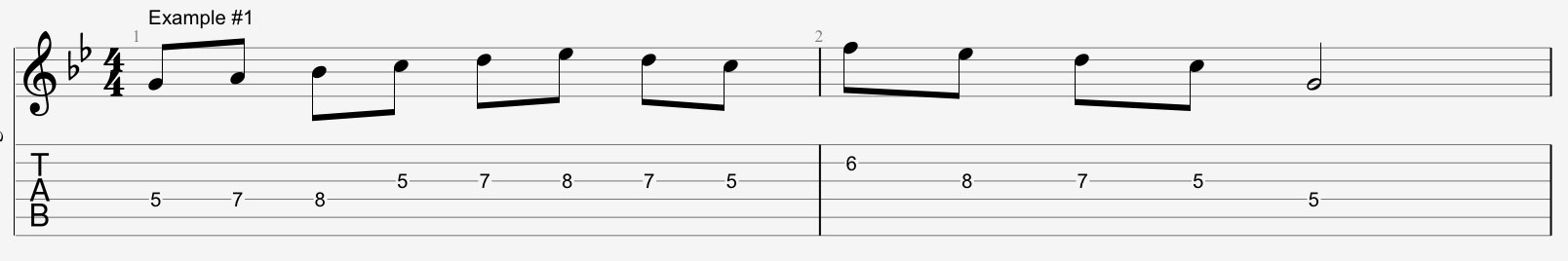

Play this melody line:

It’s okay, right? Nothing wrong with it really - it’s fine. But we can spice it up quite a bit without taking too much away from the original contour and arc by adding some intervallic leaps.

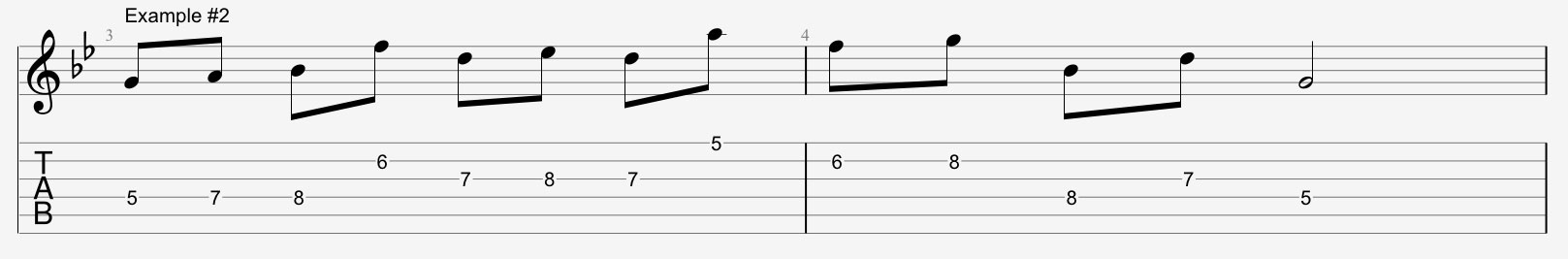

Like this:

This one starts and ends in the same place, but we’ve added a couple twists in the middle - after those first three notes, where we’ve established a pretty simple and straightforward stepwise melody, we launch it up a perfect fifth, then down a minor third, then up a perfect fifth again, then as we descend we also throw in the descending versions of a major sixth, a major third, and a perfect fifth, which look the same as their ascending counterparts, but you play them top to bottom instead.

It’s not crucially important that you know what the names of each of these intervals is, but for me, it’s really handy to know them on sight just to keep them organized. They each sound unique, so to me it’s like knowing the names of colors - you can identify something that’s purple instantly without hesitation, and intervals can be the same for you, both by sight and by sound - and it starts by just identifying them.

If you have a strong grasp on the notes of the scale you’re using, then with sheer trial and error you can come up with some really cool sounds just by experimenting with large diatonic (consisting of notes from the scale) leaps from the notes of your stepwise melody. Just jump to a note within the scale from wherever you are currently, and you can then either continue your melody up/down where you leapt to or you can leap back down to where you were, and continue your previous stepwise melody.

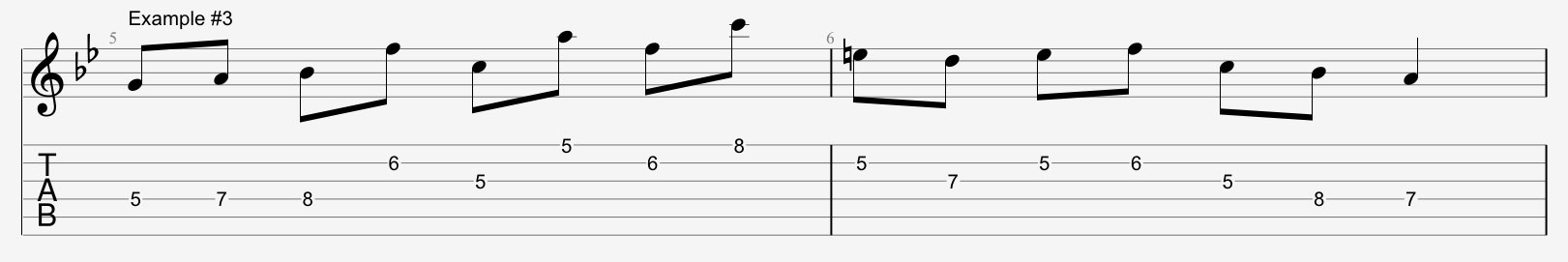

Here’s an example I concocted using this method, and I feel like it didn’t lose much melodic cohesion even with big intervallic leaps, partly because I brought it home with a nice, familiar-sounding stepwise melody:

This is something I do if I’m feeling like my melodies are sounding too stale and predictable. The possibilities within even just this one idea are pretty much endless - and this is just one cool thing you can do with intervals!

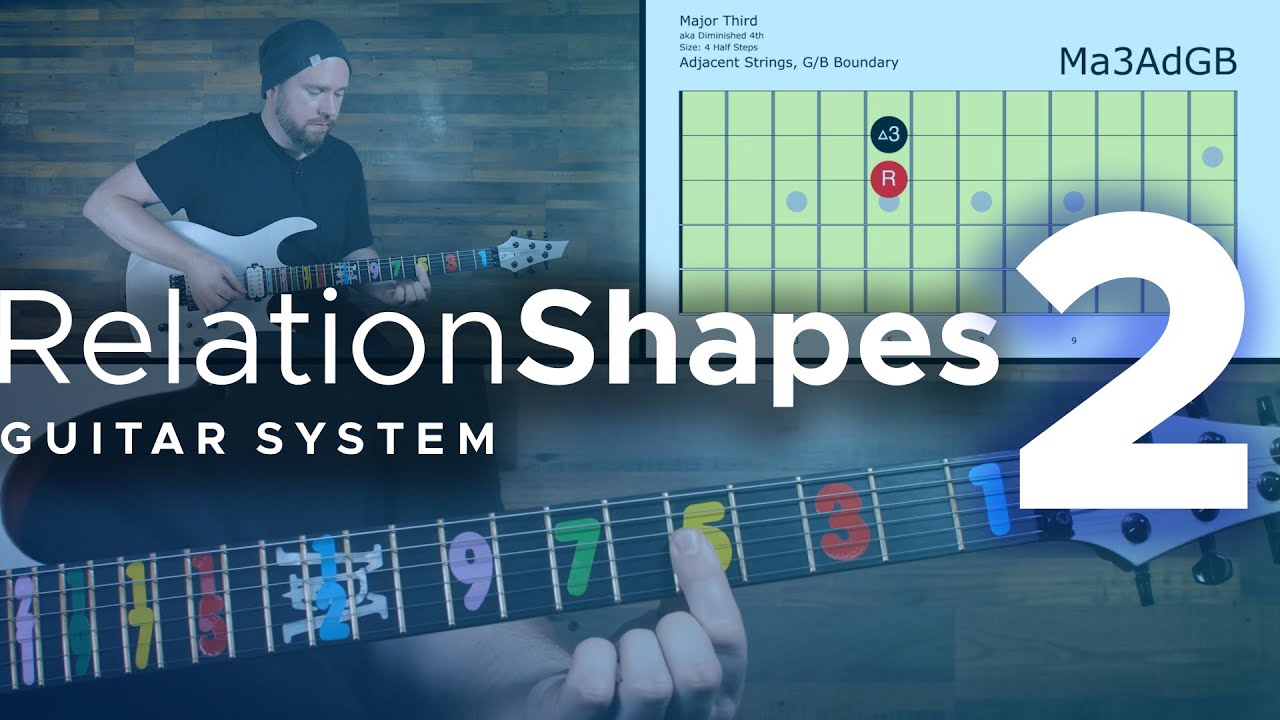

If you want to become a master of intervals, and be able to play things like this effortlessly by knowing every single shape for every kind of interval on the whole guitar, then I’ve created a one-hour course that you’re gonna want to check out - it’s called RelationShapes 2: Intervals, and in it, I’ll show you how to do exactly that.

I've even got this special ½-off coupon just for Guitar World readers like yourself – click here to get that special deal and I’ll see you over there!

"Upgrading from your entry-level acoustic opens the door to an entirely new world of tonewoods, body shapes, and brands": 6 signs it's time to upgrade from your first acoustic guitar

"I'm past my prime": 5 common excuses for not learning the guitar – and 5 body and mind-boosting reasons you should