Engineer Sterling Winfield on Recording Vangough and Working with Pantera

Sterling Winfield got his start in the music industry as a studio apprentice and live sound engineer in Dallas.

Those experiences led to his tenure as a staff engineer at Dallas Sound Lab and eventually recording and touring as a bass and guitar tech with rock and metal bands, including Damageplan, Hellyeah and Pantera, with whom he worked as assistant engineer on the Grammy-nominated album Far Beyond Driven.

His resume covers a broad spectrum of artists, including hip-hop, R&B, country, blues, choral, jazz and orchestral. He engineered progressive rock band Vangough’s latest release, Between The Madness, continuing a working relationship that dates back to the group’s debut album, Manikin Parade.

In this interview, Winfield talks about recording Vangough and the state of today’s music industry. He also looks back fondly on his time with Pantera.

GUITAR WORLD: How did your relationship with Vangough begin, and what made you want to work with them?

I was introduced to them by a bass player from another band from Oklahoma City. He said he had this really cool band and “they might want to work with you.” I reached out to Clay [Withrow, Vangough founder/vocalist/guitarist], he came down and we talked a little bit. He had some tracks he wanted me to mix. He brought his hard drive to Dallas and we started going through it and mixing. The relationship started there, five or six years ago.

You came up in analog, learned the ropes in real studios and made records when labels still ran the show. Now, with this leveled playing field and bands making no money, how can they hire you? There are no advances and most bands can’t afford a producer or engineer. What does this do to your bottom line?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It goes a little sideways and backward and “Let’s try this and see if it works.” When I say that the Internet has leveled the playing field, we’re getting down to what people really want to hear and not what they’re being told they want to hear. They’re becoming the real judge and jury. There’s still the Billboard Top 200, the Grammys, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the people that say, “This person is great and you should listen to them.”

People are sheeple, and they’re going to continue to perpetuate what we call pop, or popular music. But the real music fans, the people that love a band because they love their songs and want to own their pieces of music, that’s where the real demographic is in my mind, and they’re showing it. If a band goes out there and says, “We want to record an album. Let’s do a Kickstarter thing and see how much money we generate,” with $2,000 or $3,000 on a Kickstarter, you can make a damn good album.

I make myself accessible and inexpensive for the local-level unsigned bands so that they can get their music out there, because I do this for the music. If I were doing this for the money, I would have been a lawyer or a record company executive and I would have retired at age 30. But I love music and I love being involved with it. If you find people with good music and good songs, people are going to want to buy them and the money is there.

The money is already built into their music. They ask for it and it shows up. I’ve seen bands that are dirt poor and have badass songs and I go, “Here’s what you need to do. Talk to people who might want to invest in your song or your next gig. There’s Kickstarter and a couple of other sites where you can do these things.” Six months later, they come back, they’ve found an investor, they’ve got a Kickstarter, they’ve got the money, I record them and we do an EP. Not a lot of people are doing full albums like they used to, we don’t sit in a studio for six months or a year, but the money is there and the fans are willing to fork it over just to hear their stuff done correctly. It’s pretty amazing.

You toured as a guitar and bass tech. How did that make you a better engineer?

I never even thought about that. If nothing else, it really helps you learn a lot about yourself. You learn how to live in harsher conditions than you would at home, sitting in a nice, air conditioned studio. It makes your people skills be on point at all times. You’ve got to be able to trust a lot of people and have them trust you. There’s a brotherhood on the road. I never intended to make a career out of it. The studio is what I was meant to do. I knew I would never give that up. The road teaches you to think on your feet very quickly. It made me a better engineer, for sure, and helped me forge a lot of lifelong friendships.

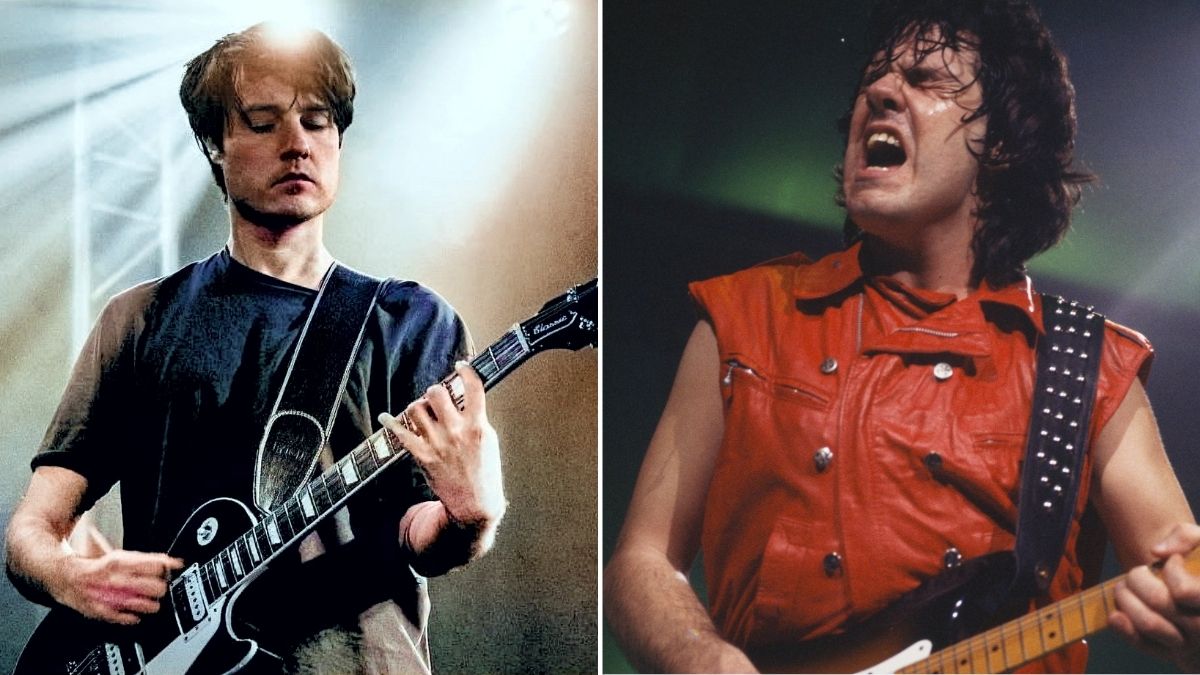

What made Pantera such a great band?

They had the ability to not only talk the talk, but they could walk the walk, and they could walk it all over your fucking face. They had raw power. That’s what they were all about, just unforgiving. Pantera were the forefathers. They could assault your senses and have you beg for more. They had this energy, and they not only delivered these cutting-edge albums, but each one broke the last one’s mold.

They would put it behind them, go on to the next one and do something heavier. Each one topped the last thing they did. They were big and bad-ass and wonderful and that’s why I loved them so much. I was a fan way before I met them. I grew up listening to all their independent stuff, and although it wasn’t what they evolved into, I knew there was something there. They had one of the bars that a lot of bands get held to and accused of having as their influences, even if they deny it. It’s one of those things that you either love or hate. They evoked that passion, that spirit.

That’s one of the things I’m most proud of. It surrounds me every day. Yeah, we had our bad times, but what a cool ride and what a great family, because they were my family on and off the road. They were a great bunch of dudes. I’ve got nothing bad to say about any of them.

Does working with a band of that caliber make you more demanding of other bands?

Sure, sure. I find myself being the jaded old man sometimes, and disappointed, but all of that comes from within me. I have to realize that if I’m having a problem with somebody, the problem is with me. I need to readjust my thinking and know that this isn’t Dime or this isn’t Vinnie. I’m dealing with someone with completely different values and feelings, and I have to readjust to that situation. There have been times when I’ve worked with bands and told them, “You’re not ready for me yet. Go woodshed for six months and call me back.”

I’ve shut things down before and told bands that “I don’t think this is working out. It isn’t for me. I don’t think it’s for you, either, and I’m going to save you all a bunch of time and money right now.” We part as friends. I don’t take their money and blow smoke up their ass. In my mind, and in the way I do things, that’s the way it should be done. Don’t waste their time. Don’t take their money if you don’t mean it. If I tried to measure every band I work with to Pantera’s level, I’d never work with anybody again. Very few people have impressed me on that level. I can count them on one hand.

Those little goosebump moments and studio magic moments don’t come around often. When they do, I try to make them last as long as they can, but they're transient and fleeting, and I have to remain humble and teachable because I’m learning something too during this process. I’m just along for the ride, and I need to be happy and grounded where I’m at. John McBride said in an interview, “Any day I can make a living in the music business is a good day,” and he’s right, especially in the climate that our business is in. To be able to do that is a huge blessing and I try not to forget that.

Some days I do. I find myself snapping at some kid because he’s wandered in drunk or didn’t practice or whatever the case may be, and we’re wasting hours trying to find another guitar for him to play, but these guys haven’t been where I’ve been, so I can’t lay those expectations on them. I’ve got to suss out each individual situation and try to make it work.

Read more of Sterling Winfield’s interview here.

— Alison Richter

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews right here.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

“Around Vulgar, he would get frustrated with me because I couldn’t keep up with what he was doing, guitar-wise – Dime was so far beyond me musically”: Pantera producer Terry Date on how he captured Dimebag Darrell’s lightning in a bottle in the studio

“He ran home and came back with a grocery sack full of old, rusty pedals he had lying around his mom’s house”: Terry Date recalls Dimebag Darrell’s unconventional approach to tone in the studio