AC/DC: The Big Chill

The critics said AC/DC would have another hit when hell freezes over. Tell Satan to put on an overcoat - Angus Young and the boys from Down Under are back with Black Ice, their cool new return to the raunch and roll that made them famous.

“It’s two different worlds,” says Angus Young, exhaling a stream of cigarette smoke into the air-conditioned comfort of a plush conference room at Sony Music’s New York headquarters. AC/DC’s lead guitarist is discussing the decades-old and probably unbridgeable gap between mass market pop and dirty, lowdown rock and roll.

“The mainstream media tend to lump everything together,” he moans. “To them, there’s no difference between Madonna, the Rolling Stones or whatever. If AC/DC were being interviewed on America in the Morning [sic] they’d probably ask, ‘Do you have a dance choreographer to work out those steps for you?’

“The trouble is, I don’t think they look at the reality of the world. The reality is that not everybody’s got nice white teeth or the full-scale beauty treatment. Not all women have silicone implants. In the real world, people just get on with their lives. And that’s where AC/DC come in. We’re in that culture; we make music for that culture; we hit them at the bottom end. We come up that way.”

AC/DC’s new album, Black Ice, hits hard and, most definitely, below the belt. The lead single, “Rock ’n’ Roll Train,” pounds along like a libidinous locomotive, running on pure raunch and hot to jump the rails. Angus and his elder brother, Malcolm, wrap their guitars around the tune’s primal beat like sibling snakes twining around Adam and Eve’s apple tree. Singer Brian Johnson wails with hellhound intensity, as if the song’s titular conveyance were running over his foot. Everything falls into place exactly as it should on an AC/DC song. Every power chord, snare crack, yelp and lead line hits with maximum intensity. Not a note is wasted.

“Rock ’n’ Roll Train” is just one of several powerhouse tracks on Black Ice. “War Machine” bristles with tribal bellicosity and a low-voiced chant that recalls the AC/DC anthem “Thunderstruck.” “Skies on Fire” is hooky as hell, propelled in the chorus by a bass melody that comes on like a sugar rush, while “Anything Goes” cooks to a riff built around a droning D string and “Rock and Roll Dream” recalls the glory days of album-rock grandeur.

Recent AC/DC albums have tended to cluster a dozen or so mediocre tracks around one strong single, but Black Ice reverses that trend. It is the best AC/DC album in years, worthy to stand alongside classics like Back in Black and Highway to Hell. Not bad for a bunch of guys in their fifties. “If you know what you do well and stick to that, I think you can appeal to the different generations,” Angus says. “You can strike a chord with them. I’ve got the brain of a teenager anyway.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

AC/DC’s record label certainly seems to be betting the farm on Black Ice. Advance security on the album was Code Orange tight, verging on paranoia. No advance discs were issued to journalists; the only way to hear the record was to report to Sony’s corporate HQ on Madison Avenue, an imposing edifice done up in black marble like some warlord’s dark castle. Rock scribes dutifully submitted to several layers of security screening and were finally ushered into a listening room under the continuous surveillance of a Sony employee, lest someone palm the disc and digitize an illicit copy. Advance reports in the music press have suggested that the record industry’s fate depends on the performance of this year’s new releases by Beyoncé, Dr. Dre, Jay-Z and…yes…AC/DC.

But even this is nothing new to Angus. He has regularly witnessed some variation on this phenomenon ever since AC/DC first hit the United States in the late Seventies, roaring out of Australia behind momentous early albums like Let There Be Rock, Powerage and Highway to Hell. “We’d be playing some big arena with two other bands like ourselves, barely known at the time,” he recalls. “And down the road, in a very small theater, would be the guy who had the number-one hit record. I thought, There’s something wrong here.”

What’s wrong, as he sees it, is that the mainstream media think only about creating hits rather than building an artist’s fan base. Thus the musical landscape is dotted with one-hit wonders whose careers never went further than one or two well-known songs. “When we were younger and first starting out in Australia,” he notes, “we found that we sold more records by word of mouth because we were playing the bars, clubs and small places and building a following. And as we got bigger we still relied a lot on word of mouth. The albums came out and we outsold the pop artists three to one. That’s why I say it’s two different worlds.”

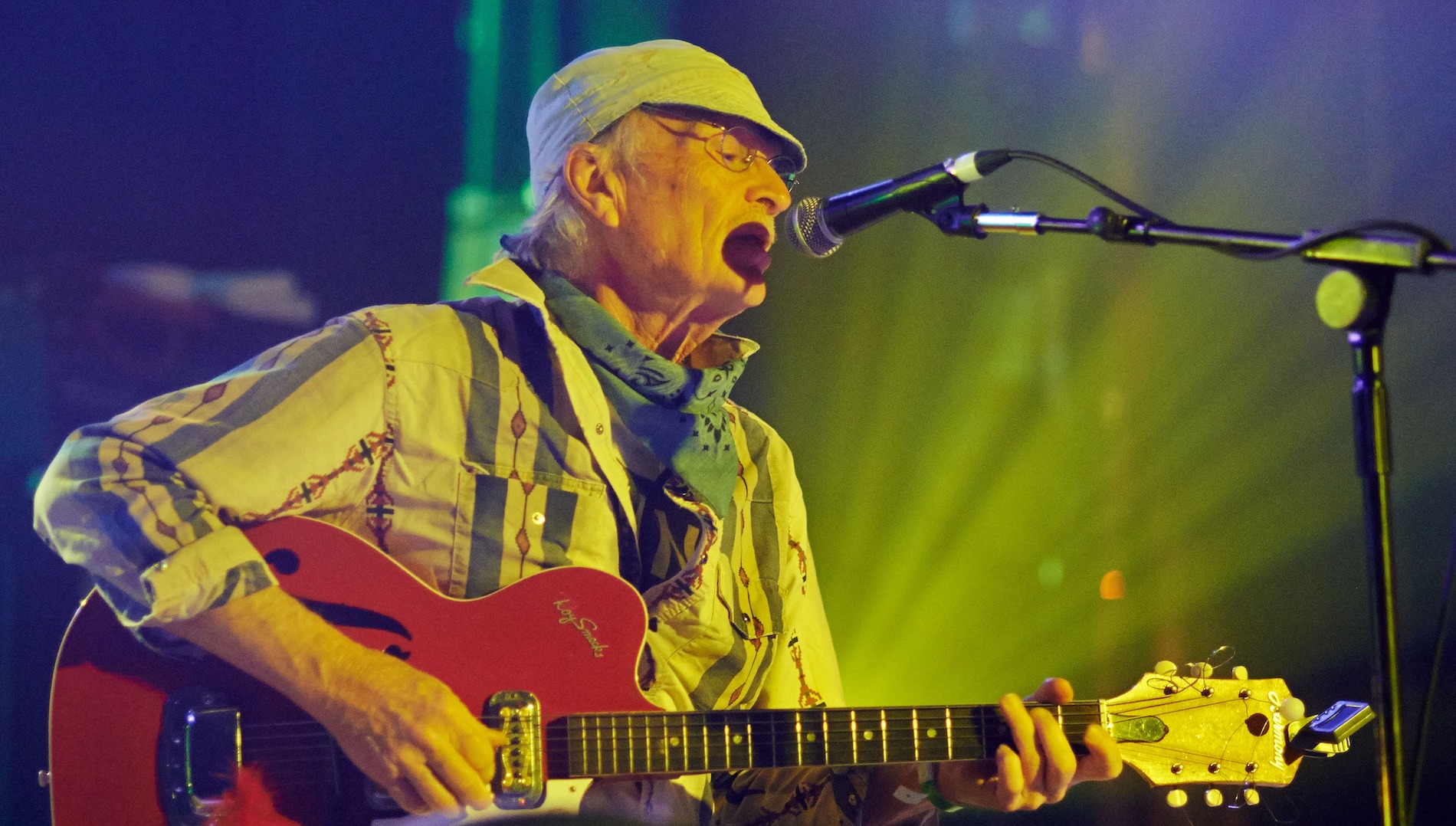

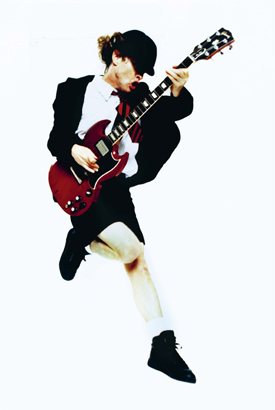

In other words, AC/DC are now being hailed as saviors of the music business because they’ve always ignored music business trends. That’s what’s so endearing about them. Empires may fall and stock markets crash, but you know Angus Young is going to come out in that schoolboy suit and rock the bejesus out of his Gibson SG, just as he’s been doing since AC/DC first got going in ’73. And you know Brian Johnson is gonna stalk the stage in a flat cap like some boozed-up workingman who’s climbed up onto the roof of his local pub. The songs are going to be tight and ballsy, crammed with smutty double entendres and nasty guitar licks. There’s something profoundly reassuring about all that.

But Black Ice definitely ups the ante, which is perhaps why expectations for it have been riding so high. One key to the album’s higher quotient of killer tunes is the fact that it’s been eight full years since AC/DC’s last studio album, 2000’s Stiff Upper Lip. So they’ve had more time than usual to cook up some great songs.

“I guess we were kinda lucky,” Angus says. “We had a bit of a break and we didn’t have a lot of pressure to put out a new album because Sony were putting out compilations and DVDs. So we could afford to sit back and say we’ll do another album when we think we’ve got all the goods.”

True enough. Sales have been brisk on remastered reissues of AC/DC’s back catalog and live DVDs like the recently released No Bull: The Directors Cut, which documents a memorable 1996 live show in Madrid. AC/DC have attained the kind of classic status where their career is as much about back catalog and live performance as it is about new releases. Still, no one—not even the Rolling Stones—can coast forever on their back numbers. And so Angus and Malcolm finally got down to work on what would become Black Ice.

“The last gigs were done in 2003,” Angus recalls. “And after a while Malcolm and I got together in a studio in London. We’d pick a couple of song ideas and play away—work a bit and then take a break when we’d begin to get stale. Take a month or two off and then get back together again for the next batch.”

The brothers Young have long been the prime force behind AC/DC’s songwriting. In the early days, the band’s original singer, Bon Scott, lent a hand, often using his own amorous exploits as a basis for lyrics. “Whole Lotta Rosie,” for instance, documents an erotic interlude with an obese Tasmanian. “She was a fair-sized girl,” Angus recalls. “I mean, they didn’t have Weight Watchers back then.”

After Scott passed away in February 1980, Brian Johnson became part of the writing team initially, sharing writing credits with the brothers Young on classics like “You Shook Me All Night Long” and “Back in Black.” But when Johnson went through a difficult divorce and legal problems during the making of 1990’s The Razor’s Edge album, Angus and Malcolm assumed all songwriting duties. It’s been that way ever since.

It’s hard to say exactly how the sibling songwriting team works. Angus seems to be more intuitive and Malcolm more analytical. At least that’s how it was when “Rock ’n’ Roll Train” came together.

“It was an idea that I had,” Angus says. “And Malcolm picked that out of a whole batch of ideas. He said, ‘That one’s a really good track—a bit different.’ He plucked it out. I didn’t see it. I’m going, ‘Are you sure?’ Sometimes it’s hard to see the woods through the trees. But as soon as Malcolm heard it, he had the idea for that vocal melody in the chorus [‘Train right on the track’]. Malcolm’s always good at that. He can show me how to spread an idea out and get the best out of it.”

Black Ice also benefited from the production expertise of Brendan O’Brien (Velvet Revolver, Bruce Springsteen, Pearl Jam). Working with AC/DC for the first time, O’Brien encouraged the band to emphasize the hooky, melodic side of its songwriting—the AC/DC of “You Shook Me All Night Long” and “Highway to Hell.” While the more bluesy, riff-driven side of the band is also well represented on the disc, O’Brien made the band dig deep for the kind of big melodies that get fists pumping and stadiums full of people singing along at the top of their lungs.

“I suppose that’s good,” Angus says of O’Brien’s melodic emphasis. “ ’cause I’m always a bit raw dog, you know? I’ve never been great with harmonies. If I write something, I just tend to mumble and get a rough kind of tune goin’. I’ll concentrate more on the swing side of it than anything—the rhythm side. But being a producer, I suppose Brendan looks at it and says, ‘I better bring out the melody.’ He could get Brian in the right vocal registers. He’s good that way.”

Rumors circulated a few years back that Brian Johnson might not be on the new AC/DC album, that the singer just couldn’t hit those bollocks-crunching high notes anymore. The fact that Brian had been off the songwriting team for a good many years lent credence to the stories, but Angus dismisses out of hand the suggestion that Johnson was ever out of the band.

“There are always a lot of rumors. A lot of times there’d be stories about Brian leaving, and he’d be sitting right there with me and Malcolm, all of us working on a new song. These days, especially with the internet, you hear all kinds of things that aren’t true. I heard that I was doing some sort of solo blues project, which isn’t true either. That’s just not me, for a start. I mean, I like blues music, but I like lots of other things, too. I certainly wouldn’t call myself a blues guitar player, not in the sense of someone like Eric Clapton.”

Black Ice was recorded at the Warehouse studio in Vancouver, British Columbia, which is also where the band cut Stiff Upper Lip. “It’s got a good vibe,” Angus says of the facility. “We do it the old way: we set up everyone in the studio and do the rhythm tracks with the whole band. That’s basically the only way we really know.”

Although Angus is AC/DC’s lead player and Malcolm the rhythm specialist, both brothers will often lay down rhythm guitar tracks. You can hear this clearly on “Rock ’n’ Roll Train” in the gracefully nonchalant way that Angus’ trebly rhythm dances around Mal’s rock-solid foundation.

“There’s no way in the world I can do what Malcolm does,” Angus says. “Believe me, I’ve tried, but Malcolm’s got his own sound. It’s very clean, very punchy, and he has his own distinct way of playing. So I’m always in amazement, ’cause when I watch and copy what he’s playing, I can’t hold it together like he does. Every now and again, I’ll do a little overdubbing on the rhythm tracks to fatten them up a bit. But Malcolm’s the guy for the rhythm. He just socks you in the jaw. It’s so big and bright.”

The Young brothers’ sibling guitar DNA is what cinches AC/DC’s unique place in the classic rock dynasty. Malcolm is the elder of the two. Now 55, he was at an impressionable age during rock’s mid-Sixties British Invasion era. The emphasis then was on tough, scrappy rhythm guitar work, catchy chord progressions and tight, melodic songcraft as exemplified by the early recordings of the Beatles, Stones, Who and Kinks, not to mention the Easybeats, the hit-making Australian beat group led by Angus and Malcolm’s elder brother George. Malcolm’s guitar playing and songwriting for AC/DC clearly bears the stamp of all these influences.

But Angus, who is 53, is more a product of the late-Sixties/early Seventies ascendancy of rock stars like Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Led Zeppelin and early metal bands like Black Sabbath and Deep Purple. In that era, the emphasis was clearly on single-note leads, extended soloing and riff-oriented song construction. And these are the virtues that Angus brings to AC/DC. So between the two of them, the brothers embody pretty much the entire stylistic lexicon of classic rock guitar. No wonder AC/DC rock like no other band.

Another advantage of having Brendan O’Brien at the production helm was that he could relate to Malcolm and Angus on a guitar player’s level. “What’s good about Brendan is he’s the real deal,” Angus says. “He’s a musician. He knows his guitar, bass, drums, piano…all of it. That’s good when you’re working with somebody. He knows where you’re coming from and you know where he’s coming from, so you’re not bogged down trying to communicate your ideas. It’s especially good for guitar. It gives you a bit of a kick up the butt. The guy’s not gonna let just anything cruise. He’ll make you work.”

It was O’Brien, for instance, who insisted that Angus play slide guitar leads on the track “Stormy May Day.” “I don’t really call myself a slide player,” Angus demurs. “But on the demo I’d done for that song I got an acoustic guitar, put it on my lap and used a cigarette lighter for a slide. I put it in the background, but Brendan heard that and kept reminding me, ‘There’s a slide on there.’ So I had to go out there and give it a try [on the master recording]. I had one slide from years back that I picked up. It was a really cool bit of Plexiglas, or something, that you wear on the pinkie. My fingers are very small, and it fit just right. But when I went to do the track I couldn’t remember where I’d put it. I said, ‘Oh well, I’ll probably find it one day.’ But they went out and found some things that were pretty close, and I used one of those for the track.”

Angus isn’t one to put an excessive amount of forethought into constructing a guitar solo. He goes with his gut, and that’s what gives his solos a great sense of immediacy and good-old rock and roll swagger. But his long years of experience have left him with a built-in instinct for what makes for a memorable solo. His approach to solos has also been shaped by his work with many great producers over the years, starting with his brother George, who produced the early AC/DC albums and several more recent ones.

“What George would do was give me a few tracks to put down solos,” Angus recalls. “I’d do one, and he’d say, ‘That was good. Now do that and do that.’ So I’d try what he’d said. And after putting down all those tracks I’d think I was finished. But he’d go, ‘No. Now take a bit of that, that and that and do it all in one.’ And off we’d go. I think he did it to teach me a lesson, so I wouldn’t sit there diddling all the time. To shut me up.”

The legendary Mutt Lange, who produced Highway to Hell and Back in Black—not to mention albums for Def Leppard, XTC, Foreigner, the Cars and Bryan Adams, among many others—had his own way of psyching a good solo out of Angus. “Mutt would just say, ‘Hmm, that’s interesting.’ And that was his code word for shite,” Angus says, laughs. “‘Oh, that’s very interesting.’ ” But I like it when somebody pushes you to try harder. You know they’re paying attention. You know they care about it. And Brendan’s good like that too. He says, ‘You’re on,’ and, ‘You gotta dial it up!’ ”

Although O’Brien brought some of his vast collection of vintage guitars and amps to the studio for the Black Ice sessions, Malcolm and Angus mostly relied on the same guitars that they’ve been playing for years—instruments that are essential to the AC/DC sound and indeed the AC/DC mythology. In Malcolm’s case it’s a heavily modified 1963 Gretsch Firebird; for Angus it’s a red 1968 Gibson SG. “I’ve lost count of how many SGs I have,” he says. “But none of them match up to that one guitar. I’ve tried getting copies of it, but no, they’re not even close. You might get the feel, but you don’t get that same kind of sound out of it. I don’t know why. I wish I did.”

On occasion, O’Brien coaxed Angus away from his number-one SG. “I’ve got a couple of other guitars that I use onstage and as spares,” Angus says. “I’ve got a an early Sixties black SG, and we’d try that one. I’ll try anything and, if it works, use it. Another guitar that I’ve got, a ’68 SG, dates from the Highway to Hell days, and I’ve used it for backing tracks and stuff. It’s a factory reject, I think—it has the number ‘2’ on it. I got it for 70 or 75 bucks when I first came to America. It was quite beat up.” (As has been the norm over his career, all of Angus’ guitars were strung with Ernie Ball Super Slinky RPS strings, gauges .009–.042.)

A few other guitars have come into play over the years. “I don’t mind a Tele,” Angus allows. “When Malcolm and I started out we only had money at the time for one spare guitar between the two of us. So we had a Tele that Malcolm picked up. And what he did was he stuck a humbucker at the bridge end and a Gretsch pickup at the neck end. So whoever broke a string first would pick up that Tele. I’d kick in on the humbucker and he’d kick into the Gretsch pickup.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Malcolm seems to be more of an avid gear fiend than his younger brother. “Mal’s got a lot of old Marshalls, and he keeps then all in good nick [shape],” Angus says. “So we have a guy tweaking them all the time, changing a valve here and there. Malcolm knows his sound to a T. So he’s always making sure the amps are just right before we do anything. That’s important for him. Mal likes a big, clean sound; he doesn’t like it if distortion starts creeping in. He likes to get it as big and fat as possible without that. With AC/DC there’s no effects, no compression. We like to get this raw, natural sound, just relying on the guitar and amp.”

Even though Angus and Malcolm had eight years to write Black Ice, song ideas were still arriving while the band was recording in Vancouver. The album was almost completed when Malcolm presented the song “Anything Goes.” With its catchy G-string guitar melody played against an open D-string drone, it’s easily one of the album’s hookiest tracks.

“Malcolm had that one when he came to Vancouver,” Angus says. “He said, ‘I’ll just play it and see what you think.’ And everyone liked it. And on his demo he had the drone going. It was a case of capturing the feel of it and adding a little bit of color here and there.”

And lest anyone question where AC/DC are coming from, four of the album’s 15 tracks contain the words “rock and roll” or “rocking.”

“Well, that’s basically what we are,” Angus pleads. “We’ve always been quite liberal in throwing the phrase ‘rock and roll’ into tracks. It’s just one of those things. Chuck Berry did it first with ‘Hail Hail Rock and Roll.’ Certain songs just seem to come to life when you add that phrase.”

Other AC/DC song ideas have come from the strangest places down through the years. The classic “Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap,” for instance, was inspired by the Sixties children’s television cartoon Beanie and Cecil. “It was a cartoon when I was a kid,” Angus says. “There’s a character in it called Dishonest John. He used to carry this card with ‘Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap—Special Rates, Holidays’ written on it. I stored up a lot of these things in my brain. I picked out the things I liked best.”

Of course, anyone attempting to deconstruct an AC/DC song must proceed with caution. Over the years the lads have managed to keep straight faces while maintaining that “Big Balls” is about high-society parties and “Cover You in Oil” is about the fine art of portrait painting. But when you come right down to it, just about every AC/DC song is ultimately about either sex, money, the occasional fight or the timeless joys of rock and roll itself. This is another key to their enduring appeal. They deal in the subjects that tend to get everybody excited.

On the new album, the song “Money Made” revisits the subject matter of the classic “Moneytalks.” The new song is a Hollywood tale, although Angus sees it as being about America in general as well. “You come to this side of the world and everything is money these days,” he says. “The focus seems to be, ‘How do we get money out of this? Do we keep that school? Is there a profit in it? Do we really need that new hospital? Can you not die quicker? Do we really have to spend money on that medicine? How old are you now?’ Sometimes you think, Can we all take one deep breath? The basics have got to be in place. Thirty years ago, a fuckin’ school never made money. Filling in a road or putting up a traffic light didn’t make money. Hospitals were there to keep people well, not make money.”

It’s tempting to see another new song, “War Machine,” as being a comment on current events. But actually it was inspired by ancient Roman history. “I was watching a thing on television about Hannibal, the guy who went over the Alps with the elephants to defeat the Romans,” Angus explains. “When Rome was in power there was another empire, which was the Carthaginian Empire. But this one senator guy in Rome said, ‘They got the best wine, the best oil, the best of everything in Carthage.’ He was basically whipping up the populace: ‘We’re gonna get you in a war.’ The soldiers were paid in wheat back then, and they were promised they’d get bigger handouts of wheat. Of course when they came back they got shat on, after doing the dirty work. I thought, Well, nothing’s changed.”

The history of ancient Rome is a subject that seems to hold a profound fascination for Angus and has provided the raw material for several other AC/DC songs. “For Those About to Rock, We Salute You” came from a book on Roman history titled For Those About to Die We Salute You by Robert Graves, which had been given to Angus by Bon Scott. And “Hail Caesar” speaks for itself. But Roman history is not the kind of subject you’d expect to interest a guy from AC/DC.

“When I was younger, I never learnt much in school,” Angus explains. “So I said, ‘Well, I’ll go to the library and read a bit—pick up a bit of info that way.’ And as a kid, you of course read what’s interesting to you, which for me was wars, the history of countries, fighting and all that stuff. I like a good book. Some fiction, if it’s good or if it’s funny. But I’ll go more for the factual stuff.”

In many ways, Angus Young is an unlikely rock star. Asked his favorite drink, he answers without hesitation, “a good strong cup of English tea.” He seems to avoid alcohol, perhaps the upshot of being in a band whose original lead singer drank himself to death. Malcolm has had his own bouts with the bottle over the years as well, so Angus exhibits little fondness for strong drink.

“That’s for other people,” he says. “Whatever they feel is good for them. I’m not a preacher. Some might like turpentine, or say, ‘What’s running that car? I’ll have a glass of that.’ But not me.”

In a sense, having a cartoonish image has enabled Angus to maintain a private life. No one looks very far past the schoolboy suit. “The great thing about the school suit is you can take it off and leave it all behind when you leave the stage,” he says. “Which I think is a good thing. So many performers get caught up in trying to live the legend 24 hours a day. That can really mess you up.”

Nor does one ever get much of a glimpse into Angus’ relationship with Malcolm. If there is sibling rivalry, they certainly don’t play it up as other notable rock bands like the Kinks and Oasis have done. “Oh, we’d be liars if we said it was 100 percent smooth,” Angus demurs. “We have our moments. But I guess blood is thicker than water. We might get pissed off with each other, but that’s part of life. As kids we’d have our differences. Malcolm would be like, ‘Get out of my room. You’re stealing my licks!’ But what we share together is AC/DC. Outside of that, we have different interests. I might read a book on history and he might read a book on football, ’cause he likes football. We spend most of our life on the road, so we see a lot of each other. The last person he wants to see sometimes is his kid brother.”

But one occasion that did bring the two of them together during AC/DC’s hiatus was Malcolm’s 55th birthday, although both brothers are now of an age when they tend to downplay such reminders of the passing years. “I think Malcolm’s like me,” Angus says. “Come birthdays, we tend to hide. They have a party and you hide in the corner.”

Angus carries his 53 years gracefully. His sandy-colored hair is shorter than it was in days of yore, and has gone thin at the top, but he looks trim and fit. The guitarist admits that he’s started working out in the past year—some weight training, stretching, a half an hour or so on a bike in the mornings. “But I’m not going to go out and join the rowing club or the Olympic jogging team,” he protests. As if to emphasize his point, he lights another in an endless series of cigarettes.

One wonders how he does it. Angus’ live performances with AC/DC are physically demanding in the extreme. AC/DC play on huge arena stages, and he’s in constant motion, running from one end of the stage to the other. Their shows aren’t exactly brief, either. Angus works harder onstage than Mick Jagger, not to mention guys half his age. How long does he see himself keeping this up?

“As long as I can do it and do it well,” he answers. “I don’t want to be struggling to do it. And touring does take up a lot of your life. So when you do it, you want to do it well. If I felt I wasn’t delivering, then I’d have to say, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ You don’t want to get on there in a wheelchair. But as long as I can feel it when I get on, and I’m putting in that energy, I’ll keep doing it.”

But does rock and roll still matter in the screwed-up, digitized, corporate globalized world of today? Angus doesn’t hesitate a second to answer.

“You bet it does. And if it’s not us doing it, it may be younger ones coming along and doing it. That’s really great too. I’m really waiting. I just wanna see them come out and go for it the way that we do. I just wanna see ’em comin’ at ya.”

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band