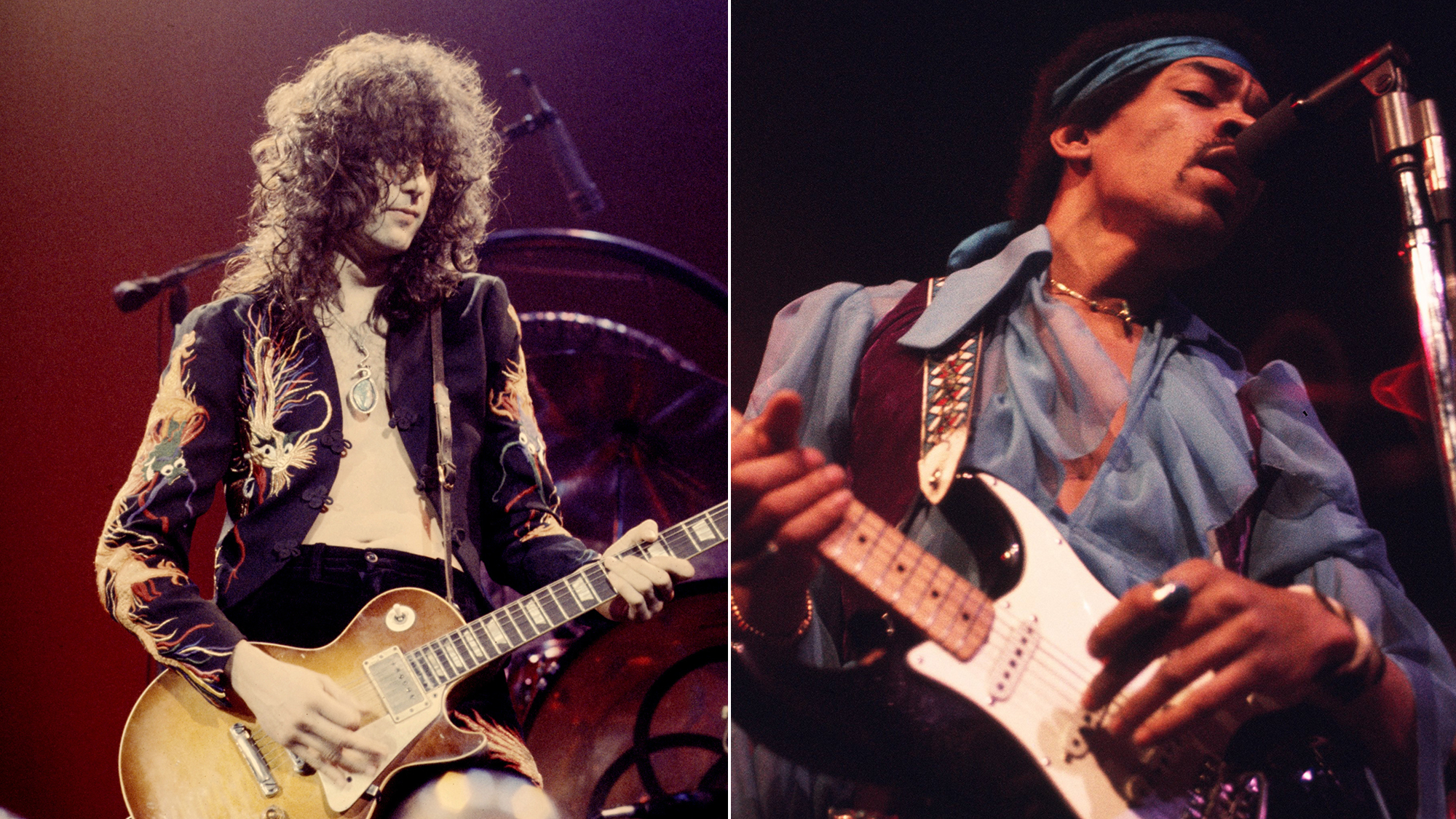

Was Jimi Hendrix Out of Control During His Final Days in the Studio? Evidence Emerges on 'People, Hell and Angels'

Was Jimi Hendrix spinning out of control during his final days in the studio, or on the verge of a new breakthrough? New evidence emerges on People, Hell and Angels, a new album of previously unreleased studio recordings.

Bassist Billy Cox has fond memories of his final days in the studio with Jimi Hendrix, recording at New York’s famed Record Plant in 1969.

But trips to and from the studio with Hendrix were another matter entirely. Cox recalls that the legendary guitarist was something of a reckless driver. A jaunt across Manhattan in Jimi’s silver Corvette could be a hair-raising experience.

“We’d go into the studio around eight o’clock in the evening,” Cox remembers, “and a lot of times we didn’t come out until noon the next day. When we came out of the studio, he’d have his guitar, I’d have my bass…and the Corvette was a two-seater. So we take off, and my face is hangin’ out the window, along with one of my legs, and Jimi’s got his guitar in the back. We’re goin’ through traffic, and I’m sayin, ‘Oh, lord, you gon’ run into somebody!’ He scared me. I’d get out at the hotel and say, ‘Whew, man! I made it safe and sound.’ ”

As fate would have it, it was drug-and-alcohol-related asphyxiation, not reckless driving, that claimed Hendrix’s life not long after the scene Cox relates. But by then, Jimi had already vastly enriched rock guitar’s lexicon of licks, tricks and aesthetics. He raised the bar for rock guitar heroism. Or as Cox puts it, “Here we are 42 years later, and we’re still celebrating his genius.”

Hendrix never got to finish the album he was working on at the time, leaving fans, rock historians and pop culture geeks perpetually wondering what he was up to in the studio during the final year and a half of his life. Back at the tail end of the Sixties, some said he’d lost the plot, that the glory days of Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland were behind him, and never to return.

Then again, there were those who said that he was on the verge of creating some new progressive form of music exponentially more revolutionary than what had come before. There was talk of a collaboration with Miles Davis arranger Gil Evans, although there’s not even a hint of that among the mountain of unfinished tapes Hendrix left behind.

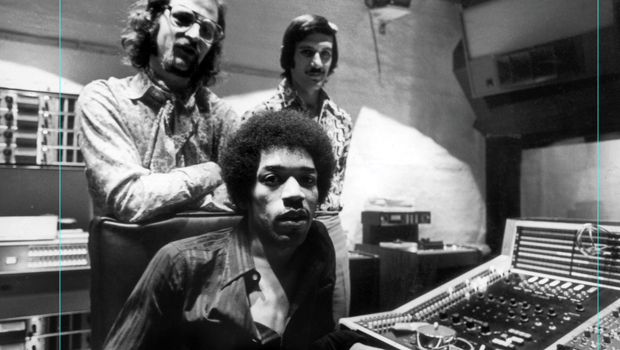

“Jimi was frustrated before he died, because I think the public didn’t understand him,” says Eddie Kramer, the recording engineer who worked most extensively with Hendrix throughout his years of fame. “He was so confused as to which way to go.”

So was Hendrix on a crash course with musical disaster, wasted on dope and wasting tape while the studio clock ticked off dollars? Or was there some grand, redeeming vision that would have turned the whole thing into another Sgt. Pepper’s, Bitches Brew or Exile on Main Street?

Elucidating the musical truth of Hendrix’s final recordings has been the almost 20-year mission of Kramer, archivist/producer/historian John McDermott, and Janie Hendrix, who is Jimi’s half sister and the head of Experience Hendrix, the company that manages the late guitarist’s estate.

In 1997, they released their best educated guess as to what that final album might have been. It was called First Rays of the New Rising Sun, the name that they conjecture was at the top of Hendrix’s list of tentative titles for his work-in-progress.

They followed it up in 2010 with Valleys of Neptune, another scoop from Hendrix’s deep barrel of end-game demos, work tapes, jam tapes, party tapes, unfinished masters and so on. McDermott, Kramer and Experience Hendrix recently dropped another glimpse of Hendrix’s final days at work in the studio, People, Hell & Angels.

“We’re filling in the library with the last missing piece, from a thematic point of view,” McDermott says. “On Valleys of Neptune, we looked at the final recordings of the Jimi Hendrix Experience and then Jimi’s first steps with [bassist] Billy Cox. ‘Here,’ we said. ‘This is Jimi outside the Experience.’ So it includes the very first recordings the Band of Gypsys made in the studio, Jimi with the band he had at Woodstock and him playing and guesting with friends like [R&B sax man] Lonnie Youngblood and [vocal duo] the Allen twins. The idea for us was to say, ‘This is all the stuff that was among his portfolio of music that was cut after Electric Ladyland.’ Hopefully it shows some of the avenues that this guy was traveling down as he was trying to decide what the future held.”

The tracks span the period from March 13, 1968, through August 1970, although the main focus is on an extended run of sessions held at the New York Record Plant in mid 1969. It was a time of profound change for rock music and for Hendrix himself. He’d just moved back from London, where he’d first risen to fame and where he recorded the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s game-changing first three albums. He was back in his home country, but all was not well.

Hendrix had parted company with Chas Chandler, his co-manager and the producer who had given shape and substance to the first three Experience albums. Experience bass player Noel Redding would soon leave the fold as well. Redding and Chandler were both exasperated by the guitarist’s newfound fondness for tinkering endlessly with musical ideas in the studio and only occasionally coming away with a master take.

But that too was a sign of the changing times. The business and aesthetics of rock music were in the midst of a revolutionary transition. Where the music industry had once viewed rock music as a passing, cash-in-quick teenage fad, more-enlightened entrepreneurs were starting to realize that rock held enormous long-range business potential, not to mention all the excitement that comes with the forging of a bold new art form.

So in a sense, Hendrix had landed in the right place at the right time when he got off the plane in New York. Two gentlemen named Chris Stone and Gary Kellgren had joined forces to create a new kind of recording studio on West 44th Street. Stone was an MBA marketing wiz connected with the Revlon cosmetics empire at the time. Kellgren was one of the best engineers in New York, noted for his pioneering work with eight-track recording and tape-based effects like flanging and phasing.

While the best recording studios had historically been cold, antiseptic, lab-like environments attached to record labels like EMI or Columbia, Stone and Kellgren hit on the idea of building an independent state-of-the-art recording studio situated in a comfortable, hip living room–style environment. Along with Frank Zappa, Hendrix was one of their first and best clients, paying a handsome hourly rate to hang out, jam and party with friends, experiment with musical ideas, strive for master recordings and generally make the Record Plant his midtown pied–à–terre.

“Oh, Chris and Gary loved Jimi,” McDermott says with a laugh. “At the end of the day it was like, ‘Just keep stacking those tapes up, fellas. Let him be in there as long as he wants to.’ Because they’d be able to say, ‘Hey, we got the top guy at our facility.’ And the bills always got paid. It wasn’t like they had to chase someone to get paid. Jimi paid his bills.”

This is the somewhat amazing part. The recording funds weren’t coming from Hendrix’s record label, Reprise, recoupable against future album sales in the usual music manner. Instead, Jimi was footing the bill himself.

“It never went through the record company,” McDermott confirms. “It drove his management and his accountant crazy, but the bills went to his management company, and they paid for all those sessions.”

For Hendrix, the investment seemed well worth it. Before he hit it big, he toiled for years as a studio guitarist, playing budget, nail-it-in-one-take R&B sessions. Hendrix relished the idea of having the hippest new studio in America as his atelier and all-around bachelor pad. He’d also started to assemble his New York team. Kramer was shipped over from England, where he’d distinguished himself as an engineer at London’s celebrated Olympic Studios. Stone has vivid memories of Kramer alighting from the car sent to pick him up at the airport, decked out in a cape. And when Kramer wasn’t around, Kellgren’s world-class studio engineering chops were at Jimi’s disposal.

Even before setting up shop at the Record Plant, Hendrix had shown a marked tendency to view recording studios as party spaces, and the guest list was pretty wide open. “The hangers-on became a problem,” Kramer says. “They became a problem for Chas, and certainly for me. Sessions would be tough, because Jimi couldn’t say no to his buddies. He’d have invited the street sweeper and the cleaning lady and the record company president with him.”

But now, with Chandler out of the picture and the Experience on the skids, some of Jimi’s buddies started to make it out of the party room and into the band. Some of them earned their keep in that capacity better than others. With Redding’s imminent departure from the scene, Hendrix called on Billy Cox, an old friend from the guitarist’s days in the Army and a musical colleague who’d played many a chitlin circuit gig with the guitarist in the early Sixties. Cox had deep experience backing greats like Sam Cooke, Wilson Pickett, Slim Harpo, Freddie King, Gatemouth Brown, Rufus and Carla Thomas and many others on stages, recording and TV studios. He was also solid as both a musician and a personality.

“Jimi Hendrix and I were musical confidants when he began his musical career,” the bassist says. “And I was his musical confidant till the end.”

Cox began by recording with Hendrix and Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell, but soon another drummer entered the picture. Buddy Miles came from the same R&B roots as Hendrix and Cox, and had gone on to be a larger-than-life figure in rock music, a voluble, volatile veteran of the Electric Flag with guitar hero Mike Bloomfield and his own Buddy Miles Express. The Hendrix, Cox and Miles trio would soon be known to history as the Band of Gypsys.

“We were all the same age, and we had all come up under the R&B influence,” Cox says. “I mean Buddy was with Wilson Pickett, and I played behind Pickett when he came to Nashville. So we all played the same kind of music and had a lot in common.”

One of Cox’s many musical virtues was his ability to mesh equally well with both Mitch Mitchell and Buddy Miles. “Mitch was more soul influenced from a jazz perspective,” Cox explains. “And Buddy was a hard-hitting rock and roller. But both of them were good, and I had no problem playing with either one. I came out of the Pittsburgh/Philadelphia scene, and I was familiar with a lot of the jazz artists from there. I tried to play a little jazz years before, and I liked Mitch’s influence. And then with Buddy, you had the R&B, blues, gutbucket hard rock thing, and I liked that also. That was part of my DNA.”

In that light, it’s interesting to compare one of People, Hell and Angels’ standout tracks—the Hendrix standard “Hear My Train a Comin’ ” laid down with the Cox/Miles rhythm section in May 1969—with a version by the Experience just a month earlier. While the two recordings are very close in arrangement and tempo, Hendrix clearly sounds more relaxed with Cox and Miles and tears off a blindingly brilliant guitar solo. He’s one of the few guitarists on earth who’s amazing even when he’s noodling in the studio at four in the morning. The People, Hell and Angels set packs quite a few solo guitar epiphanies, albeit cast as diamonds in the rough among unfinished tracks.

“What’s so cool about Jimi is you can hear how excited he gets when there’s a dialed-in player or players on the track,” McDermott says. “It lifts him to a different place. You can hear it when you listen to ‘Voodoo Child’ on Ladyland, and you can hear it with Billy and Buddy on ‘Hear My Train.’ Whenever he feels like the people with him are locked in, he can soar.”

Fans of the Band of Gypsys’ one official recording, the highly regarded, self-titled live album from Fillmore East, will be especially interested in People, Hell & Angels, which contains no fewer than four studio recordings by the short-lived trio.

“When Jimi went to Billy, he didn’t say, ‘You’re gonna replace Noel,’ ” McDermott recounts. “He said, ‘Come up and help me.’ And when Billy first came in April of ’69, it was really about making good on some of these songs that Jimi had struggled on with Noel. Noel was a tremendous musician and deserves a lot of credit, but I think there was something with Billy. In all the turbulence of Hendrix’s life, it was important for him to have a steadying friend, who would understand his desire to work on demos over and over again until he felt he had it, whereas Noel was hoping to get it in one or two takes and move on. I think that kind of philosophical difference really was critically important.

“And as for Mitch Mitchell versus Buddy Miles,” McDermott continues, “I think Mitch was Jimi’s guy, but he did realize that Buddy brought something special for certain songs that was almost part of his personality. That thump and that excitement was different from Mitch, but it certainly fits a song like ‘Earth Blues’ [another frequently recorded Hendrix composition, performed with the Cox/Miles rhythm section on People, Hell and Angels]. You hear it. When you compare that with the version that has Mitch on drums, it’s markedly different. The R&B funk vibe is there. It becomes a different song.”

Hendrix was clearly searching for the right rhythm section sound for the material he was developing. A lot of the 1969 recordings seem like an effort to arrive at a definitive basic track over which Jimi could record vocals and the filigreed layers of guitar overdubs that were essential to the Hendrix magic.

But was the material really worth that much effort? Most of it is blues-based stuff or blues covers, which was not unusual for the time. Blues records were extremely popular in 1969, and blues-based artists like John Mayall, Canned Heat, Johnny Winter, and the Al Kooper–Mike Bloomfield tandem were enjoying major success. Traditional blues artists like B.B. King, Albert King and John Lee Hooker were also crossing over to the rock audience in a big way.

But the preponderance of blues-based material among Hendrix’s final recordings seems to disprove theories that he was onto some bold, new progressive jazz-rock direction. And if the folks at Reprise were expecting another Hendrix hit on the order of “Foxey Lady,” Purple Haze” or the guitarist’s popular cover of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” they would have been disappointed; there is certainly nothing of the sort to be found among the tracks on People, Hell and Angels. If anything, at the end of his life Hendrix seemed to be heading back to his bluesy roots. And few people had more of a right to go back there than him.

“By the time I got onboard, I’d say his direction had kind of changed,” Cox confirms. “Some of his songs from that time, like ‘Freedom,’ ‘Up from the Storm’ and ‘Dolly Dagger,’ were based on little riffs that we’d come up with together back in the early Sixties. Some of them were insane at the time. Jimi would say, ‘Man, if they heard us play some of this stuff, they’d lock us up.’ We didn’t write any of that stuff down. We remembered it. Jimmy called them ‘patterns.’ I call them ‘musical riffs.’ We had a lot of them in our heads.”

Another virtue of the Record Plant, complementing its great gear and a penthouse vibe, was the fact that it was right around the corner from the Steve Paul Scene, at the time one of New York’s hottest rock and roll clubs. Hendrix would drop by to jam with artists on the bill, including one notable run sitting in with the Jeff Beck Group. He’d also round up musicians from the club and bring them over to the Record Plant to hang out and cut some tracks, perhaps most famously tapping Steve Winwood (Spencer Davis Group, Traffic, Blind Faith) and Jack Casady (Jefferson Airplane, Hot Tuna) to play on “Voodoo Child” from Electric Ladyland. But that kind of thing went on all the time, according to Cox.

“We’d start at eight P.M. but maybe stop at around 12 or one in the morning and go out. And at that time, the Scene, Ungano’s and a lot of clubs like that had a lot of the big artists playing there. Jimi would say, ‘I’m recording over at the Record Plant, come on by.’ And we’d go into studio B at four A.M. or so and just have fun for a couple of hours. I was the new kid on the block. Didn’t know a lot of people. And all of sudden I’m jamming with Stephen Stills, Johnny Winter, whoever.”

Or even some lesser lights of the rock fraternity. On the evening of April 21, 1969, Hendrix and Cox stopped by the Scene and ran into members of the Cherry People, a group that had got to Number 45 on the 1968 pop charts with the psychedelic bubblegum track “And Suddenly.” They were in town to get out of their deal with Heritage Records and had dropped by the Scene to console themselves, having failed to secure a meeting with the head of the label. Their road manager, Al Marks, himself a guitarist, had met Hendrix backstage on a few prior occasions. On the strength of this, Marks made bold to approach Hendrix’s table. Marks has vivid recollections of the evening.

“Jimi said, ‘Sorry I don’t remember you. But hey, you play in a band? You got a drummer?’ I said, ‘Yeah, he’s right here.’ He goes, ‘You wanna do a session with us tonight?’ I looked at him: ‘You gotta be kidding. You serious?’ He goes, ‘Yeah, man, meet me at four o’clock at the Record Plant.’ He meant four A.M.”

Marks, Cherry People drummer Rocky Issac and guitarist Chris Grimes couldn’t believe their luck when they were buzzed into the Record Plant building and shown into the studio. Gary Kellgren was already in the control room setting up for the session. The three Cherry People were even more amazed when Hendrix himself turned up at around 4:20. He sent Marks out to park his Corvette while he set up the recording room to suit his requirements. Marks recalls Hendrix using a pair of Acoustic amps and cabinets for the session, which may have belonged to the Record Plant.

Once everything was ready to go, Jimi asked, “Okay, who’s the drummer?” Issac was duly installed behind the studio’s kit; Marks and Grimes were assigned to play percussion. Both Marks and Issac recall working through versions of “Roomful of Mirrors,” the Elmore James song “Bleeding Heart,” “Stone Free,” a freeform jam called “Drone Blues” and “Crash Landing.” But things didn’t go particularly well. Issac was extremely nervous and not at all used to Hendrix’s practice of just kicking into a song and expecting all the players to follow him.

“I went over to Billy Cox and said, ‘Billy, I’m used to learning a song first,’ ” the drummer recalls. “I don’t know what’s going on here, and I’m scared.’ And Billy said, ‘I don’t know what’s going on either, but I’ve got the advantage of having played with Jimi quite a bit and I’m able to follow him.’ I said, ‘Well, he’s not cueing me in or anything, and I keep messing up.’ He said, ‘Do the best you can.’ ”

The evening went downhill from there. “I think it was around 10 or 11 in the morning when we got done with ‘Roomful of Mirrors,’ ” Marks says. “Meanwhile, we’d gone back into the control room after every take while Jimi stayed in the studio. He wouldn’t come out into the control room. And Gary Kellgren had a bowl full of rolled joints and an ashtray filled with cocaine. After every take, we’d light up a joint and pass it around.”

“Anything you wanted to take was available,” Issac adds. “Alcohol, coke, speed, pot everywhere. There was plenty of everything. The whole time I’m having an anxiety attack. I couldn’t drink enough. I couldn’t take enough speed. I was falling apart. But Jimi was so generous and gracious. I felt he was disappointed. But he took me in the control room where he was mixing down ‘Stone Free.’ He sat me down at the controls and showed me how to pan the drums from left to right. Pretty soon I’m sitting there with him doing a mix.”

Also in the control room that evening was Devon Wilson, Jimi’s main lady at the time and the subject to the song “Crash Landing,” a forerunner to “Dolly Dagger” that finds Hendrix excoriating Wilson’s hard-drug use and the toll he saw it taking on their relationship. One of the famed late-Sixties’ supergroupies, Wilson was also involved with Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, Eric Clapton and Duane Allman at various times. She passed away under mysterious circumstances at New York’s Chelsea Hotel just six months after Hendrix’s death. Marks remembers her as, “very tall, very thin, very beautiful. She sat in the corner and just smoked. Didn’t talk. She was as high as the rest of us.”

So it is perhaps no surprise that the evening didn’t amount to much in terms of viable master recordings. “It was funny to watch Gary Kellgren as the night progressed,” Marks says. “He started messing up a little bit, and that’s when he called the session that night. He couldn’t make it sound right anymore, so it was like, ‘Okay, we’re done. We’re wasting time and tape.’ That’s exactly what he said. When the faders started looking like double faders, that was it.”

What is surprising, given the evening’s unrewarding musical trajectory, is that Hendrix asked Issac, Marks and Gaines to return for another session a few nights later. Jimi gave the drummer $400 for the night’s work and $100 each to Marks and Grimes, with the promise of the same again when they returned. When Issac got back to New York from the Cherry People’s D.C. home base for the second session, he garnered some further insights into his Hendrix’s life at the time.

He met Jimi at the office of his manager, Mike Jeffrey. A hard-bitten, old-school rock-and-roll business sharpie with a reputation as a gangster—some even say that he arranged Hendrix’s death—Jeffrey didn’t welcome Jimi’s latest protégé with open arms. He clearly wasn’t pleased to fork over cash to cover hotel, meal and incidental expenses for Issac and another member of the Cherry People, guitarist Punky Meadows, who hadn’t been engaged to play on the session but had tagged along to meet Hendrix.

“I felt like Mike Jeffrey would have rather just taken a gun and shot me than given me two dollars,” Issac says. “Jimi knew he was getting robbed, moneywise, but I don’t think that was the big thing for him. He wanted some freedom, it seemed to me. Jimi and I were talking, and he told me, ‘I’m so fucking unhappy. All the guy [Jeffrey] wants me to play is ‘Foxey Lady’ and ‘Purple Haze’ over and over and over. Everything I write he wants to sound like that.’ I think he was at a point where he had to do something. He was so unhappy with management. He didn’t say anything about being unhappy with Mitch or Noel Redding. And of course he didn’t say anything unkind about Billy Cox. But he did say that Mike Jeffrey was just about to kill him.”

Fortunately, everybody stayed away from the control room ashtrays during Hendrix’s second session with the Cherry People, on April 24, 1969, which yielded the take of “Crash Landing” heard on People, Hell & Angels. “Jimi came in very businesslike and knew what he wanted to do,” Marks recalls. “It wasn’t the same social atmosphere as the first night. He was very direct and to the point. Apparently he had listened to the roughs. He came in and said to me, ‘Okay, if you’re going to play maracas, you need to do this, this and this. He directed each musician. He had like a bandstand thing to hold sheet music. There were blank sheets of paper on it and he was writing lyrics for ‘Crash Landing’ as he was playing. He’d tell us to keep going and he’d be writing down lyrics and starting to sing them. Then he’d say, ‘Okay, from the top…let’s go.’ ”

“He was magical,” an awestruck Issac recalls of Hendrix’s studio performances. “Seeing him in the studio was like seeing him onstage. Maybe not quite as much theatrics as he displayed onstage, but he didn’t make mistakes. There was genius there. That’s the feeling I got.”

“His fingers were the size of rulers,” Marks marvels. “They were huge!”

The evening also yielded a version of the aforementioned “Bleeding Heart” posthumously released on the Valleys of Neptune set and arguably more adventurous than the Cox and Miles version of the same tune heard on People, Hell & Angels. The more up-tempo feel and funk-jazzy chord substitutions of the Cherry People version certainly offer a more radical recontextualization of the Elmore James original than the straight-ahead slow-blues reading that Hendrix, Cox and Miles gave the tune. With all due deference to the “anything Hendrix ever did was sheer genius” crowd, it’s possible that the law of diminishing returns had begun to set in as 1969 wore on.

Certainly, the Cherry People’s eyewitness account of their two evenings at the Record Plant with Jimi Hendrix puncture the myth of Hendrix’s infallibility. It’s clear that many of Hendrix’s Record Plant evenings were more like a party than a serious attempt to capture master recordings. Cox takes credit for reining a lot of that in.

“By the time I got on board, all that kind of stuff changed,” he says. “It had to change if we were going to get any quality work out there. Jimi and I talked about it, and he knew what he had to do. He had to buckle down and get it together.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, Cox says that Devon Wilson’s visits to the studio became less frequent once the bassist was firmly ensconced. “It tapered off and she didn’t come in as often,” he says. “It changed. Prior to me getting onboard they’d say, ‘Oh happy day, let’s go out and just have some fun.’ But we kind of got to the point where we had to get down to brass tacks and get serious about the thing. The studio no longer became a place of play; it became a place of work. A sacred place. I told Jimi, ‘We’re lucky to be here. We have to make the most of it.’ ”

As one of the world’s biggest rock stars, and one notorious for his sexual prowess, Hendrix certainly didn’t lack for female companionship. The ladies were more legion than the joints in Kellgren’s “hospitality bowl.” But Hendrix’s relationship with Wilson cut deeper than that. It was a dysfunctional pas de deux of drugs, music and love.

“There were certainly other women in his life, but I think Devon was the one,” McDermott says. “She was the one who was fascinating to him, in terms of personality, obviously her beauty and also her outlook. It was a very passionate relationship between her and Jimi, but it wasn’t always steady. She was fiercely protective of him, in a certain way. I’m told by friends that she always thought she was advocating for Jimi and his best interest. Although, when Jimi built his own studio, Electric Lady, one of the things they did—and something she was very much in favor of—was put a closed-circuit camera on the door so they could see who was trying to buzz their way in. And there were many nights when Jimi would see Devon at the door and not let her in. He didn’t want the drama. But what person doesn’t go through that in that kind of relationship?”

Adding to the romantic turbulence in his life, Hendrix was in the midst of a full-scale business and legal crisis. When Chas Chandler walked, Hendrix lost not only the creative partner who had helped shape his most successful songs and recordings but also the “good cop” on his management team. As a former bassist with the highly successful British Invasion group the Animals, Chandler was a musician and could empathize with Hendrix’s musical aspirations and relate them to his business concerns far more harmoniously than the more mercenary Jeffrey. Hence, Hendrix’s remarks to Issac about Jeffrey’s just wanting him to play “Purple Haze” over and over again.

Legally, Hendrix was battling drug charges at the time, as well as a lawsuit filed by Ed Chalpin of music publishing company PPX Industries. Chalpin claimed that the guitarist had a contractual obligation to PPX dating from 1965 and thus superseding Hendrix’s management agreement with Jeffrey and Chandler. Chalpin stood to gain a sizable chunk of all revenue earned by the Experience and their three top-selling albums, if not all of it.

The compromise was to give Chalpin the proceeds from a Jimi Hendrix album, the live Band of Gypsys recorded on New Year’s Eve 1970 at the Fillmore East, plus a piece of any and all future Hendrix profits. While revisionist critical zeal has placed the Fillmore disc on an artistic par with Hamlet and the Mona Lisa, it was nothing more than a quickie live album banged out fast and cheap in order to chill out Chalpin. According to Eddie Kramer, Hendrix himself was less than pleased with the album.

“I don't know that it was something Jimi liked 100 percent,” Kramer says. “I think he was disappointed in some of the excessive [vocal] warbling of Buddy Miles. There was a tremendous amount of editing done on it. There was a huge amount of jamming and stuff that didn’t quite fit on the record. The editing was a little untidy at points. But having said that, I think it’s a wonderful example of Jimi being able to play with a reasonable amount of freedom.”

“Mitch had gone to England when Jimi got into the problems,” Cox recalls. “[Jimi] was threatened with a lawsuit. So it was decided that we’d do a concert album, and I said ‘Well, I’m in.’ That’s what friends do. And Buddy was around at the time.”

But the Band of Gypsys didn’t always fare as well onstage as they did at the Fillmore shows. A subsequent concert, at Madison Square Garden, was a notable disaster, the band retreating from the stage halfway through its second number, offering apologies to the crowd. This proved to be the group’s final live performance. Events like these gave rise to turn-of-the-decade feeling that Hendrix had perhaps lost it. This impression was compounded by the uneven, somewhat shambolic performance that he turned in at Woodstock with his ill-advised, under-rehearsed and unfortunately named six-piece ensemble, Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. With Chandler gone, there was no one to tell Hendrix when he had a bad idea.

“I think the core band of Jimi, Mitch and Billy, were great at Woodstock,” McDermott says in defense of the guitarist and his ramshackle backing. “I think the other guys [guitarist Larry Lee, percussionists Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan] were trying, but they’d just never played something that big before, or with something that powerful. They were used to playing clubs and things like that.”

Larry Lee was another old buddy of Jimi’s who’d just come out of the Army, where he’d seen service in the Vietnam War. Lee would go on to many years of success as Al Green’s musical director and songwriter. But in 1969, he’d just begun making the uneasy transition from the killing fields to a society that had been radically remade in the wake of civil rights, the hippie scene, psychedelia, the sexual revolution and other sociocultural phenomena of the late Sixties. It was all a bit too much.

“Larry, God bless him, had just come back from Vietnam and wasn’t quite ready for the hurricane that was Hendrix’s popularity and all that went with it,” McDermott says. “Had Jimi employed him on select songs, you would have seen real value come out of his contributions.”

The two tracks on People, Hell & Angels that feature the Gypsy Sun and Rainbows lineup show them in a much better light than their Woodstock performance. Their studio recording of the ubiquitous “Izabella” is certainly tighter than the Woodstock rendition, with Lee effectively doubling Cox’s bass line much of the time and playing a supportive role overall. And those who mainly think of Larry Lee as the guy with the out-of-tune guitar and ridiculous headgear at Woodstock might be surprised to hear his artful jazzy comping on “Easy Blues,” a 12-bar jam from another one of Hendrix’s long nights at the Record Plant.

“I came up with this little riff,” Cox recalls of that impromptu recording. “I just kept playing it. I didn’t know the tape was going. Jimi looked at me and started laughing—jumped in and started jamming. We just did that to loosen up the fingers. We laughed because it was just a riff.”

“I think Jimi was really intrigued by the idea of having that second guitar, that rhythm guitar, in there,” McDermott says. “And Larry was a sympathetic figure. He wasn’t trying to out-duel Jimi or anything like that. He understood rhythm comping and things like that. And that’s one of his real benefits.”

“Larry was part of that same R&B thing as me and Jimi,” Cox adds. “He came from that time period. Jimi, at one point, felt like he needed assistance. Because a lot of times we were playing these riffs, the bass and the guitar together, but he wanted a guitar to keep doing that when he was playing solos. But he didn’t really need that. When the deal went down, he didn’t need any help.”

But what really brought an end to Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, in Cox’s view, was not musical considerations but the dictates of “the office,” by which he presumably means management. “That group had problems because the office didn’t want it to be,” Cox says. “And so it no longer was. [Management’s thinking was] ‘We started with this [three-piece power trio] formula. Stick with the formula.’ ”

In the midst of his own troubles and the search for a new, post-Experience musical direction, the legendarily generous Hendrix still had time to help out his friends. That side of him is reflected on People, Hell & Angels by two tracks where he happily played sideman to some of his old cronies. One of these recordings is a high-energy, old-school R&B track “Let Me Move You,” led by vocalist and sax player Lonnie Youngblood, with whom Hendrix had worked in the mid Sixties. Youngblood and Hendrix’s Record Plant recording of “Let Me Move You” is arguably the most outstanding track on People, Hell & Angels, an absolute scorcher.

“Just listen to what Jimi’s doing, comping under Lonnie,” McDermott says enthusiastically. “Crazy!”

The rhythm section of Hank Anderson on bass and Jimmy Mayes on drums is so unquenchably on fire that one wonders why Hendrix didn’t just draft them to be his new backing band. He’d worked with Mayes around 1966 when they were both in the touring lineup of Joey Dee and the Starlighters, a group that had scored a big hit back in 1961 with “The Peppermint Twist.”

“Yes, you could have seen Hendrix in a little club with Joey Dee in ’66,” McDermott says. “And then, six months later, he’s doing ‘Hey Joe’ and he’s a star in England. The time frame is amazing.”

And once Hendrix shifted operations from the Record Plant to his own brand new studio, Electric Lady, in mid 1970, one of the first projects he undertook was to overdub some hot guitar on “Mojo Man,” a track by the singing duo of Arthur and Albert Allen, a.k.a. the Allen twins. The two were old friends of Jimi’s and were recording at the time as the Ghetto Fighters. Like “Let Me Move You,” the tune offers eloquent testimony that Hendrix’s abilities as an accompanist and supporting player had been by no means diminished by his massive stardom.

Electric Lady was to have been Hendrix’s salvation—artistically, financially and otherwise. “The idea was, ‘Hey we’re going to stop paying the Record Plant a couple of hundred thousand dollars a year. Now we’re gonna have our own place,’” McDermott says.

“For almost a year and a half prior, Jimi had had no supervision. So a lot of time went into experimentation," Kramer says. “But as soon as Electric Lady was finished, he came in and it was like, ‘Wow, this is my place!’ The amount of work we accomplished in just four months—from May through August—was amazing.”

Today an institution on 8th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village, Electric Lady had previously been a venue called the Generation Club, which Hendrix had planned to purchase and turn into another hip Manhattan nightspot. “But Eddie Kramer was the guy who came in and said, ‘Hey, don’t just have a little night club with a recording studio. We’ll make this the best recording studio in the world!’ ” McDermott says. “Eddie explained it to Jimi, and Jimi said, ‘Okay, I trust this guy. We’ll do it.’ ”

While Hendrix had paid for the Record Plant sessions out of his own pocket, had had to take a loan from his record label to float Electric Lady, deepening his obligation to Warner/Reprise and giving the company additional leverage when it came to his forthcoming, vexatious and long overdue album. One reason why Gary Kellgren, rather than Eddie Kramer, had engineered many of the Record Plant sessions in 1969 is that Kramer was downtown getting Electric Lady together much of the time. And while Hendrix’s Record Plant sessions may have seemed like one long party out of bounds, the guitarist allegedly knew exactly where the gold lay among the mountains of tapes he’d piled up there in mid 1969.

“Eddie Kramer told me that one of the first things they did when Electric Lady opened in May of ’70, even before they actually recorded anything, was that he and Jimi went through all the tapes that they had pulled over from the Record Plant,” McDermott says. “And that Jimi knew exactly which ones he wanted to play. He was like, ‘Hey, listen to this one. I want you to hear this song.’ And it would be ‘Roomful of Mirrors’ from November 1969. ‘Ezy Ryder’ was another one. And they started to figure, ‘Okay, we’ll put a fuzz bass on this, and I’ll overdub some guitar…’ And then there were other songs where they said, ‘Our new studio sounds so good, let’s just recut this one.’ ”

Of course Hendrix never got a chance to do any of that. By July he was back on the road, playing a troubled tour of Europe with Cox and Mitchell. Cox flipped out on acid; not everybody shared Hendrix’s legendary ability to eat loads of LSD and still be more or less functional. The group was booed in Germany. “I’ve been dead a long time,” Hendrix said, all too prophetically, at the end of a bad night onstage in Denmark. A few days later, on September 18, he died in London.

There is clear evidence that Hendrix knew he was in trouble musically. “When he went to England, he looked up Chas Chandler about three days before he died,” Kramer says. “And he talked to Chas about getting the old team together. I could see why he was frustrated. I’ve always maintained that what he needed was a year off—a time away from touring and the pressures of the record company and management, a time to think about where he wanted to go.”

But had he lived and even been able to take some time off, would Hendrix, producing himself for the first time, have been able to pull a coherent album from the sprawling mass of variant takes and alternate lineups he’d accumulated during the year and a half prior?

“At one point, he made notes about making it a three-album set,” McDermott says, “which was pretty ambitious. It was around the time when Electric Lady opened. People, Hell & Angels was one of the tentative titles he’d written down, so it comes out of that period. He knew he had this bounty of material and he said, ‘Okay, we’ll make a three-album set,’ when he had Reprise banging on his door for just a single album.”

McDermott is certain that, had Hendrix lived, he would have finished the sprawling album, if only because of his financial obligations. “He had to pay back Warner Bros. for the loan he’d taken to build Electric Lady, and had made his first payment in August prior to his death,” he says. “And with the pressure of having to deliver the Band of Gypsys album to settle that litigation, I think you would have seen Jimi pull the record together. Now would he have been able to keep it a double, much less a triple? Who knows? Management and the record label might have said, ‘Hey, we need 10 songs and we need them now.’ Or Jimi may have said, ‘Give me a month and we’ll have the rest done.’ He made a lot of progress prior to his leaving for Europe. It’s certainly possible that they could have had something, if not for the fourth quarter of 1970, then the first quarter of the following year.”

So what we’re left with on posthumous releases like

People, Hell & Angels

and

Valleys of Neptune

are essentially basic tracks—or attempted basic tracks—waiting for overdubs. But so much of the beauty of Hendrix’s music lies in his gift for weaving gossamer webs of guitar overdubs and lyrics that combine hallucinogenic, Dylan-esque imagery with the wry wit of a soul shaman. Without those things, we’re left with something that feels, at times, painfully incomplete.

“I think the basic work tracks were there and solid,” Cox says. “The problem was words. A lot of times Jimi was lost for words, trying to put words together and make them right. And then his overdubs—that was his way of talking to you. The man was incredible with backward tapes.”

So newcomers to Hendrix are heartily encouraged to start with Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland, the finished masterpieces. Releases like People, Hell & Angels will mainly be of interest to completists, the “any Hendrix is good Hendrix” demographic, and the kind of trainspotter market that has sprung up in the wake of the Deadhead board tape-trading phenomenon.

As for the rest of us, rather than force ourselves into another semi-sincere rapture about another set of marginal Hendrix outtakes, it would be more meaningful and respectful to view them for what they are: the sound of a great artist trying to jam himself out of a jam, not at all sure of where he was going and not entirely in control of the steering wheel. These rough-hewn and half-hatched tracks actually become more poignant in that light.

At the end of the Sixties, who really knew where he or she was going? At the time, Clapton, Page, Beck and Townshend were also in the midst of major artistic transitions and career reinventions. Hendrix was certainly determined to get there with them. Two days before his death, he said as much in his final conversation with Billy Cox.

“He said, ‘Hey man, we gotta get back in the studio Friday and change a few little things and get it right,’ ” Cox recalls. “ ‘They’re raising hell about getting it out.’ And I said okay. We had maybe 15 songs he wanted to work on.”

Cox seems to have mixed feelings about the fact that—for himself and Hendrix, unlike most other musicians—“even our practice tapes have been exposed to the public. And all of my wrong, bad notes have been exposed. But, hey, people can’t get enough of Hendrix.”

Does he think Hendrix would have been comfortable with all of us hearing his works in progress?

“I don’t think so,” Cox says. “With the perfectionist he was, I think he would like to have something completed. That’s what he was all about. He was a perfectionist when it came to the music. One wrong note and he was upset. ‘Oh man, I messed this up.’ That’s how he was. That’s what made him Jimi Hendrix.”

Photo: Getty Images

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.