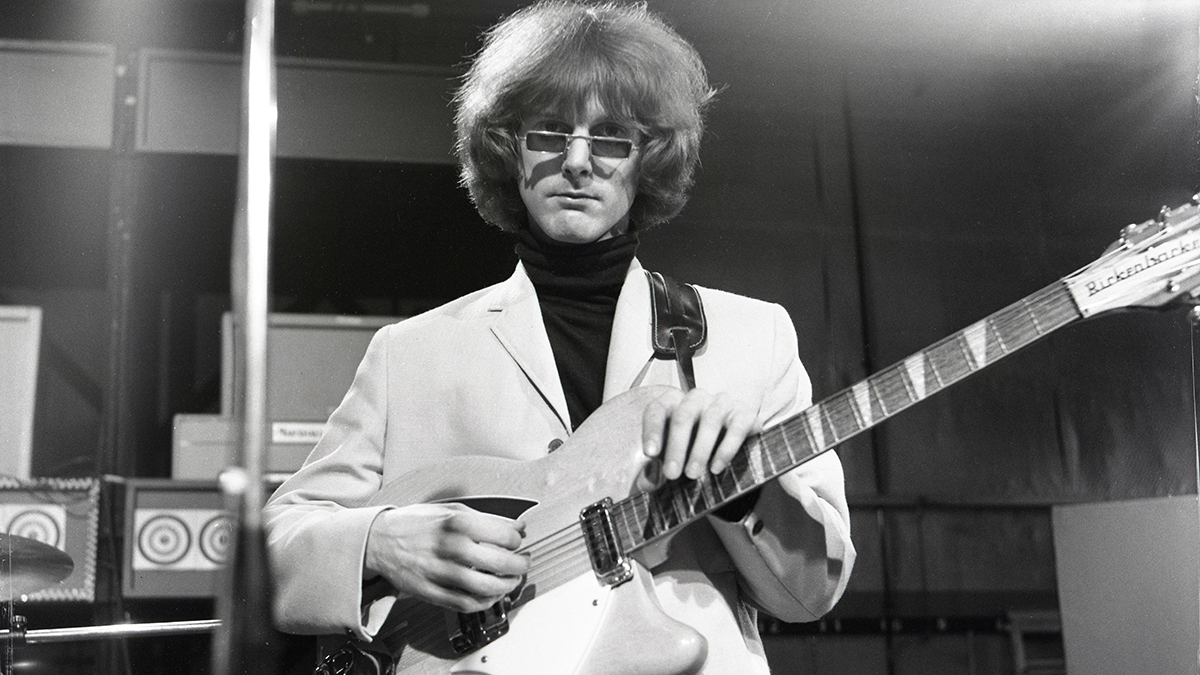

Rex Brown Recalls the Making of Pantera's 'Cowboys from Hell,' 'Vulgar Display of Power' and More

From the May 2013 issue of Guitar World.

While Pantera vocalist Philip Anselmo and the Abbott Brothers—guitarist Dimebag Darrell and drummer Vinnie Paul—were flinging insults at each other in the press throughout 2003, bassist Rex Brown remained largely silent.

His ex-bandmates viciously blamed each other for the demise of Pantera, the band that held the torch aloft for metal throughout the Nineties and paved the way for metalcore.

But Brown refused to choose sides. By then, he and Anselmo were performing together in Down, and fans might have expected he would take the singer’s side. But Brown continued to say nothing. Instead, he let the resounding notes of his bass express the pain and frustration he felt for what had become of his band.

“Vinnie drew this imaginary line in the sand,” explains Brown, who is currently wrapping up the second album by his new band, Kill Devil Hill.

“He said, ‘You’re either on our side or not.’ I didn’t want to take sides. Every fucking day before Dime was killed [in December 2004], Vinnie would email me when Phil would say something stupid in the press and go, ‘See what your boy said?’ I was like, ‘Dude, why is he my boy? Because I wanted to get out of your bus because you were throwing fucking tacos at everybody because you’d lost your mind on booze?’ The whole thing was ridiculous, but I never talked about it.”

Until now. In his revealing memoir, Official Truth 101 Proof: The Inside Story of Pantera, Brown stops short of blaming anyone for Pantera’s breakup and the subsequent murder of Dimebag Darrell. Instead, he and co-writer Mark Eglinton spend the majority of the book addressing the formation and development of Pantera through five legendary albums. In the process, Brown analyzes how four musicians that were once closer than most families grew apart because of their differences in personality, musical tastes and choice of extracurricular activities.

Brown has particularly strong recollections of the six major-label albums he recorded with Pantera. In this Guitar World interview, he gives us an unvarnished, no-holds-barred look at the making of those records and of his life with the original Cowboys from Hell.

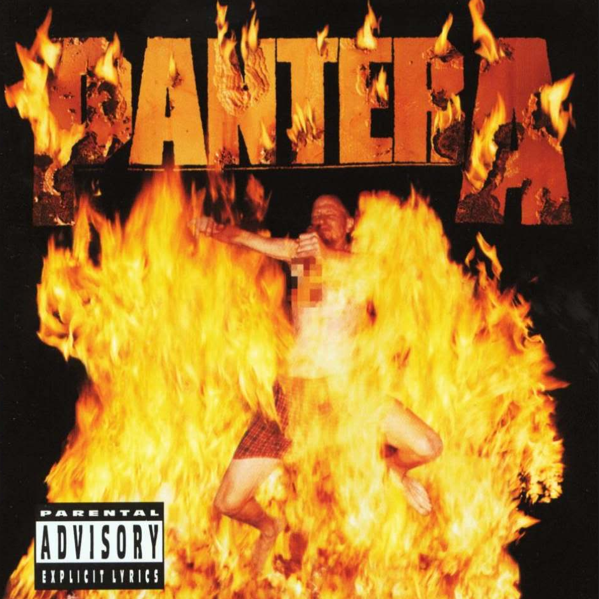

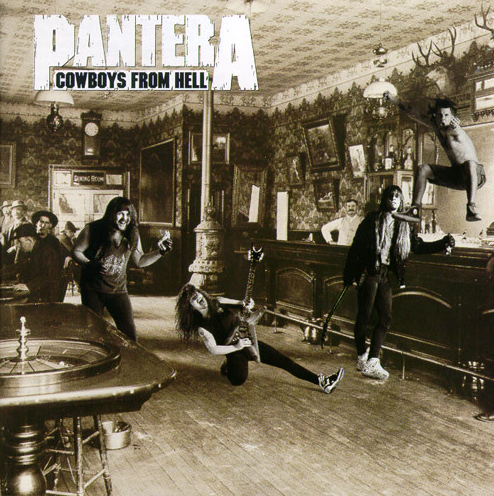

Cowboys from Hell (1990)

While we were writing the songs for Cowboys from Hell, we were listening to a lot of different kinds of music—a lot of Metallica, Slayer, Mercyful Fate and Minor Threat—and that changed our sound. We had grown such a huge following in Texas by then that we could play one set a night and draw 2,000 people. Since we didn’t have to play six shows a night anymore, we had more time to spend in the Abbotts’ studio [Pantego Sound], and we became total perfectionists.

Vinnie would lay down all the drums, then Dime would play guitar. We’d put the bass on last. We turned all the drum channels off, and I just played along with Dime’s track. That became known as “the microscope.” If something was off, we’d get a razorblade and cut and splice the tape. We didn’t have Pro Tools back then. And that’s what created our trademark sound, where the guitar and bass are just spot-on.

By that point, Dime had already surpassed all of his influences as a player, and we were making a lot of money playing Friday and Saturday nights within a radius of Dallas, Houston, Austin, San Antonio, Shreveport and New Orleans. Then, after getting turned down 29 times, we finally got signed to Atco. The thing is, that actually made our financial situation worse at first. We weren’t playing shows, so we didn’t have any money coming in. So I had to get a job. Me and our lighting guy, Sonny, got gigs putting up lights for fashion shows. It actually turned out real cool. We met all these fashion models, got laid all the time and made a month’s rent a night.

But playing with Pantera back then was even better. We were such good friends, and our chemistry was undeniable. Dime would make these riff tapes on his four-track and bring them in, and we’d turn them into songs. One day, Dime came in with this tape loop of a lick he played over and over in a high register. It drove us crazy, because he wouldn’t stop playing it. That’s what became “Cowboys from Hell,” and it was the start of the power groove every band follows today.

As much as you still hear that song, when it came out no radio stations would play it. One of my favorite memories is when we did “Cemetery Gates.” Dime already had the riff in the song where it starts getting heavy, but we didn’t have an intro. One day, I picked up an acoustic guitar and messed around with a part, which we recorded.

We recorded a piano in reverse so that it created this big swell of sound at the end of the section. When we put the acoustic intro together with the heavy part, there it was. That was huge for us, and that’s how all those sessions went. We were all working together with Terry Date, who we liked a lot, even though our first choice was [famed metal producer] Max Norman. But he canceled at the last minute and we got Terry, who we bonded with from the start.

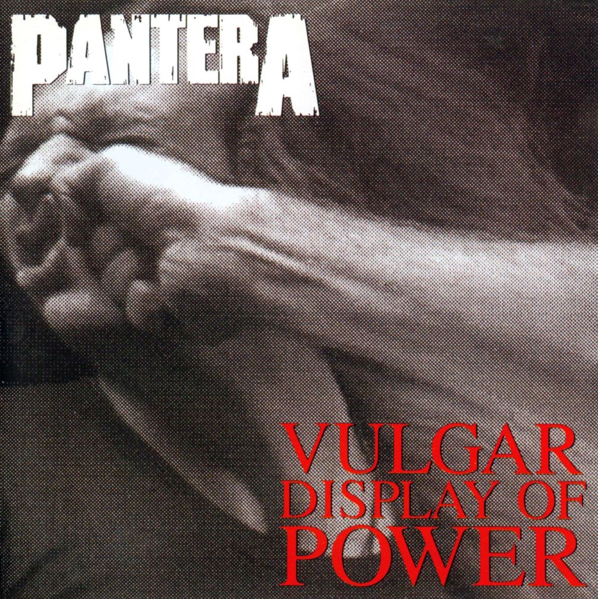

Vulgar Display of Power (1992)

When we got back from touring for Cowboys, the music scene had changed so drastically. You had Nirvana on one side and Metallica’s Black Album on the other. As good as that record is, it’s no Master of Puppets. We figured this was our chance to be the heaviest game in town. Dime had riffs pouring out of him. He’d bring them in, and it was hard to choose between them, because they were all so good. One time, Dime and Phil walked out and smoked a joint and came back with the idea for “A New Level.” A couple hits of weed and we were all flying. It was so easy to play, but it was the chemistry we had that made it sound so good. That’s how it was with us. I mean, anybody can write something like “Walk,” but to play it like we did, with that groove—that’s pure chemistry. Even “Fucking Hostile” is totally brutal but hooky as hell. This was the second record we did with Terry Date. He and Vinnie worked hand in hand to get the perfect sound, and Dime was writing riffs that were better than any band out there and taking his solos to an entirely new place. That record just came easy. All the riffs on Cowboys had been written by me and Dime. Philip came in with his own ideas on Vulgar, and that made us even heavier. After it was mastered, we had a tape of the record and we put it in a cassette player and played it for everyone at the label, and their jaws hit the fucking ground. If you play an album for someone and they say, “Yeah, man, I fucking love it,” that’s cool. But when nobody says anything after it’s done and they all have blank stares on their faces, and then someone finally says, “Holy shit!” then you know you’ve done something great. As blown away as everyone was by Vulgar Display of Power, it was the tour opening for Skid Row that changed everything for us. Vinnie had met up with them on tour and drank so much that he threw up all over their dressing room. But they had a good time, so they asked us to go on tour with them. Philip was really resistant at first, and I told him, “Look, there’s two ways we can look at this. We can view it the hard way and say, ‘Fuck you all! We’re gonna tear you apart!’ Or we can take the crowd with us every fucking night,” which is what we did. We turned all these hair farmers into Pantera believers. Vulgar was our second real record, so no one could say Cowboys was a fluke. The songs came out at the right time, and we tore it up every night.

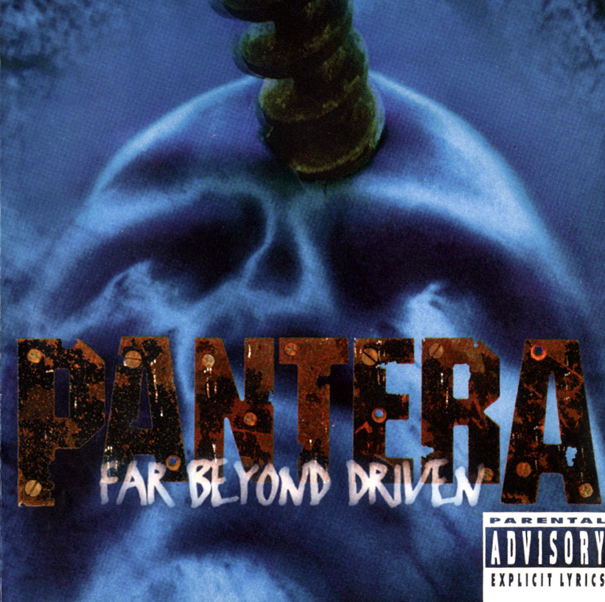

Far Beyond Driven (1994)It would have been easy for us to write another Vulgar Display of Power, but fuck that. We wanted to try something completely different that was even heavier. We moved everything up to Jerry Abbott’s new place in Nashville, and that’s the first time we started taking breaks between recording. We’d do three or four songs, put them on tape, let them sink in and then go back in and do more. That was about the time that Dime started messing around with the Whammy Pedal and Vinnie was getting completely crazy about getting this clicky sound on his drums, and that required a lot of takes and a lot of tweaking our sound. We drove Terry crazy. But we had been playing through the same gear for 500 dates between 1989 and 1994, so we felt it was time for experimentation, and we did tons of takes of everything, which is why it was our most expensive album to do. “I’m Broken” was the first single. That was a classic southern groove, and we remixed that thing 16 times. But we were raging. Take a song like “Good Friends and a Bottle of Pills.” Where the fuck does that come from? Out of the blue! We just bashed it out. Dime came up with a lot of those riffs at soundchecks, and he wrote other ones on the shitter. He always had an acoustic guitar in the bathroom. He’d go in there to take a dump and come out with an amazing song. We also covered Black Sabbath’s “Planet Caravan.” I played keyboards on it and fretless bass. Vinnie played congas. And Dime’s solo…to this day, I can’t listen to it. Just talking about it chokes me up. And Dime did it first take.Everything was happening. We renegotiated our contract with Warner Bros., and they gave us a huge amount of money each. When stuff like that happens, it can either ruin you and wipe the band out or you can bond together, which we did. Part way through the recording, we left Nashville and went back to Dallas Sound Lab, in Texas, and from then on it became one big fuckin’ party. We were boozin’. Vinnie was doing a lot of Ecstasy. Me and Dime were just taking little dabbles here and there, but Vinnie was out of his mind, and he was co-producing this thing, so he’d sometimes get real crazy. It took a long time to finish the overdubs, because the brothers were partying so heavy, but we were still “all for one, one for all,” even though Philip had moved back home to New Orleans when he was done with his vocals. That removed him from the equation, which was probably a good thing.

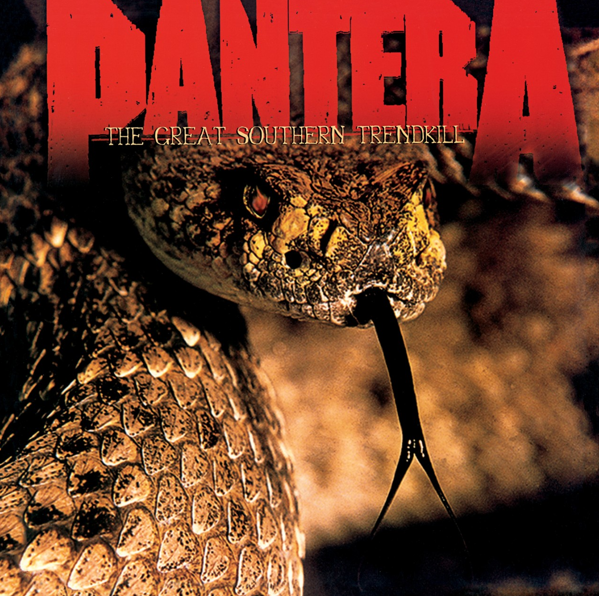

The Great Southern Trendkill (1996)Metal is a full-blown contact sport, especially the way we did it. So it was only a matter of time before Phil was gonna need something for the damage he caused himself. We used to jump 15 feet in the fucking air, and I’d usually land on my feet and feel the shock on my knees, which are shot now. But Philip would make these giant jumps and land on his fuckin’ ass. I used to always think, Fuck, man, that’s gonna hurt later.Back then, we would wake and bake. That was just a given. So that made us a little foggy. But at one point, I noticed Phil was fuzzier than usual. One day when we stared doing The Great Southern Trendkill, he looked at me and slapped his armpit [a technique to inflate a vein prior to shooting heroin]. I went, “What!?” I’ve never stuck a needle in my arm. I used to watch some of my friends shoot up, but I would never do it. No way. I hadn’t seen that reference in 10 years, and Philip doing that at me made me go, Oh shit! I hope he’s not doing what I think he’s doing. Sure enough, he was doing smack. And he was a wreck through the writing sessions of Trendkill. We were all so burned out by that point. A lot of the discipline and structure we used to have went out the window. I’m not crazy about two or three songs on the album, but there’s a lot of good stuff on it. It was all created very spontaneously. We didn’t go back and re-record anything.That record was even more experimental than Far Beyond Driven. Far Beyond still had a coherent structure, and on Trendkill there was hardly any. Dime wasn’t even bringing riff tapes in anymore. So we winged it, and Terry just rolled tape, and a lot of the random stuff we captured is pioneering. And of course, the more we worked on them, the more cohesive the songs became. It was the first time Philip didn’t track vocals with us, which left Dime leery, because he didn’t know what to do with the leads. But he got it done anyway, and it was killer. Just listen to “Floods.” That’s the three of us locked in, and it’s got all these different shades to it and all these dynamics, and Dime’s solo couldn’t be better. In the end, we were psyched about the record, and we toured it to fucking death.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.