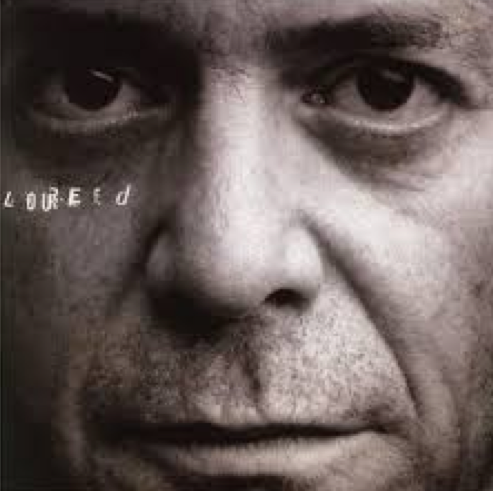

Lou Reed Talks About the Velvet Underground, Songwriting and Gear in 1998 Guitar World Interview

From the GW archive: This feature originally appeared in the September 1998 issue of Guitar World.

“Wanna hear more?”

When Lou Reed asks you a question, you know you’re being tested. For the past quarter of an hour, he’s been holding forth on the subject of power tube distortion. Now he wants to know if I’d like him to keep going.

Will an affirmative answer prove me a serious guitar aficionado, or a major chump willing to squander the precious interview time that Reed is so notoriously loath to grant?

Seated behind a big desk in his Soho office space, he looks like some intimidating schoolmaster, peering at me through frameless bifocals. Do I wanna hear more? Uh, sure Lou. Across the desk, Reed’s craggy face remains expressionless. “If your eyes start to glaze over,” he finally says, “you’ll tell me.”

Reed’s fanatical obsession with guitar gear is well known among luthiers and equipment manufacturers. It seems oddly out of character with his (slightly) more public persona as the great dark poet of American rock, the Godfather of Punk and recent subject of PBS television’s dignified American Masters documentary series. Avant garde art icons aren’t supposed to be gear whores. But then Lou Reed never does what he’s supposed to.

He seems to take perverse delight in confounding expectations and thwarting would-be theorists. He even puts his fans to the test. This has enabled him to reinvent himself repeatedly throughout the course of his 32-year career. And to write one of the most diverse, thoughtful and provocative portfolio of songs in all of rock.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

On Reed’s latest album, Perfect Night, he revisits many of his finest songs, re-exploring their variegated emotional terrain through the medium of amplified acoustic guitar. Recorded live at the July ’97 Meltdown Festival in London, the disc is an “unplugged” retrospective of Reed’s stunning career, from his earliest material with the hugely influential Velvet Underground right up to his latest work on the rock musical Timerocker.

As Reed explains in the following interview, it was a piece of guitar equipment—a feedback suppression device called the Feedbucker—that was the catalyst behind this new album. Is he putting us on? To quote the man’s own publicist: “With Lou, you just never know.”

Lou Reed was doing surprising things with guitars even before he started the Velvet Underground in 1965. As a staff songwriter for a hack mid-Sixties label called Pickwick Records, he penned and produced a dance craze single called “The Ostrich” which featured what the author called The Ostrich Guitar: a conventional electric with all six strings tuned to the same interval.

“I’d seen this guy—I think his name was Jerry Vance—tune the guitar where every string was the same,” says Reed. “I thought, ‘What an amazing sound!’ So I filed that one away.”

“The Ostrich” failed to set teenage America on fire. But one of the musicians on the recording date was the classically trained viola player John Cale, who soon joined forces with Reed, guitarist Sterling Morrison and drummer Maureen Tucker to form the Velvet Underground. With guitars, electrified viola and madly overdriven combo organs, they took feedback and noise to new extremes. Meanwhile, Reed’s lyrics took rock down a dark street where it had never been before, opening up a world of S&M fetishists, transvestites, junkies, pimps, pushers and prostitutes.

He drew his observations from books and life—particularly the social whirl surrounding pop art superstar Andy Warhol, who took the Velvet Underground under his wing, teaming them with the arrestingly beautiful German actress/model/chanteuse Nico for their first album, The Velvet Underground & Nico (Verve, 1967). Songs like “Heroin,” “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “Sister Ray” provided much inspiration for the punk rock revolution that would erupt a decade later.

The bondage/mutilation shtick so beloved of modern acts like Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson owes its existence to Velvet Underground songs like “Venus in Furs,” “The Gift” and “Lady Godiva’s Operation.” Today, the Velvets are a celebrated rock band; but they went largely under-appreciated in their own time. They were a bit too dark for the sunshine Sixties.

By the early Seventies, Reed had moved on to a solo career, membership in the glam rock elite and a commercial high point. His Transformer album (RCA, 1972), produced by David Bowie and Mick Ronson, became one of his best-selling records ever, propelled by the liltingly subversive hit single “Walk on the Wild Side.” Album rock radio played the heck out of Lou’s live opus, Rock and Roll Animal (RCA, 1974), particularly the disc’s version of the Underground’s “Sweet Jane,” which featured extended axe-twiddling from ex-Alice Cooper guitar men Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner.

Reed could have rehashed these successes and ridden the gravy train for decades, as many Seventies rock stars did. Instead, he chose to put out records like 1975’s infamous Metal Machine Music (RCA): 61 minutes and 43 seconds (four vinyl LP sides) of unrelenting, multitracked, tape-manipulated and audio processed guitar feedback.

In that one sustained, prophetic blast Reed set the stage for Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham, No Wave, Sonic Youth, The Jesus and Mary Chain, My Bloody Valentine and Noise Pop. The very next year he did a complete 180-degree turnaround and released Coney Island Baby (RCA), a subdued album with country rock overtones. With the arrival of New York’s CBGB’s scene circa ’76-’77, Lou Reed was acknowledged and lauded as the Godfather of Punk. His 1978 Street Hassle album (Arista) is charged with the nasty vigor of that vital new chapter in rock.

The Eighties brought Reed’s lyrics into a new phase. His penetrating observer’s gaze got turned inward. With the superb ex-Richard Hell & the Voidoids guitarist Robert Quine on board, albums like The Blue Mask and Legendary Hearts (both RCA, 1982) unflinchingly chronicled Lou’s own problems with relationships, drugs and alcohol. When, by the end of the decade, it seemed like Reed had tapped this confessional vein dry, he found yet another songwriting voice, one of his most powerful: the politically engaged, deeply enraged voice of the landmark New York album (Warner Bros., 1989).

Songs like “Dirty Boulevard” and “Busload of Faith”—both reprised on Perfect Night—have become the best-known Lou Reed songs since the Transformer era. New York also introduced Reed’s mature electric guitar tone—a keenly focused clean sound with incredible presence and formidable wallop. This tone has proven an ideal vehicle for Reed’s guitar style, with its distinctive use of finger vibrato in open chord shapes. In turning his attention to amplified acoustic guitar, Lou Reed has taken one further step in his lifelong quest for the purest yet baddest sound ever heard.

GUITAR WORLD: The Velvet Underground’s overall sensibility was markedly different from anything else happening in rock at the time. But on a purely guitaristic level, were you influenced by stuff that was going on?

I’d been listening to [avant garde jazz artists] Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman. Of course I was not trained to play like them. I couldn’t read and write music. I couldn’t even begin to think of having technique like that. But I certainly had the energy—and a good ear. So that’s what I was listening to, along with guitar players like James Burton and Steve Cropper.

Who doesn’t try to copy Cropper? He’s a great guitar player. You know, it’s not all about soloing. It’s about those parts that guys like Burton and Cropper played. And the Velvet Underground, we were about parts. Although some of the solo work grew out of having discovered feedback on electric guitar and liking that. I was just trying to get the good feedback and get rid of the bad feedback. It was a matter of where you stood in those days. It’s amazing I can hear anything today after doing that for a couple of years. I had my ears tested. I’ve been so lucky. I’d just be deaf after shows with the Velvet Underground. We were kids. Who knew anything?

Back then, especially.

They would have these tests saying, “Mice go deaf from being exposed to this.” So in all the clubs they’d say, “Fine, don’t bring a mouse to the club.” But we had a rule in the Velvet Underground: no blues licks. There were people who were really good at that. But that’s not what we were about.

Where did the notion first arise, for you, that the subject matter of songs like “Heroin” or “Sister Ray”—addiction, junkies, transvestite whores—was something that could be presented in a pop or rock song format?

Well, I’d been reading [beat writers] [William] Burroughs and [Allen] Ginsberg and [Hubert] Selby. I was a big fan of certain kinds of writing. I had a B.A. in English. So why wouldn’t I? It seemed so obvious and it still does. There was a huge uncharted world there. It seemed like the most natural thing in the world to do. That’s the kind of stuff that you might read. Why wouldn’t you listen to it, too? You have the fun of reading that, and you get the fun of rock on top of it.

It seems obvious now, but…

It seemed obvious then. Well, to me.

Sure, there had been protest music, folk music, but nothing like the level of literary realism you brought to it.

I can’t conceive how it’s anything other than the most obvious idea imaginable. If I’d written that stuff in a book, people wouldn’t have even looked sideways at me. Well, maybe they even would’ve looked sideways at me for putting it in a book. But I mean, this stuff existed long before I showed up on the scene. It’s in old blues songs.

And now you have gangsta rap and all the rest of it. Well, way back then, “Sister Ray” was all about that same kind of stuff. And “Venus in Furs,” I didn’t write the book. But what a great book to throw into a song. [The song, as well as the band’s name, was inspired by Michael Leigh’s book on sadism and masochism, The Velvet Underground—GW Ed.] All these things were available to write about.

In some ways, that makes it a little hard for me now. Because I’ve done that. I can’t write “Venus in Furs, Part II” or “Heroin, Part III.” Back then, though, that’s the kind of subject matter I was playing around with. But it was always balanced by what I thought were really pretty love songs. It’s kind of an odd juxtaposition. But I was someone who had a pretense toward writing. With the kind of background I had, the reading I was doing, the people I was around, all that was going on around me, it would have been strange if I was just writing “moon and June” songs. And if I did write that kind of thing, I felt I would really have to craft it. Which is what “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is. And “Pale Blue Eyes,” “Femme Fatale” and “All Tomorrow’s Parties.”

Is songwriting an easy or a labored process for you? Do you revise a lot?

I rewrite, yeah. I’m a believer in rewriting. That’s an old habit. I make things up on the spot—spontaneously. But in the end, I rewrite. I might get hung up on one word and keep on changing it until I feel it’s right.

Leonard Cohen once showed me some of his notebooks. For every song he writes, he’s got a big, thick notebook filled with variant lyrics and alternate versions. You don’t rewrite that much, do you?

Well, I do it on a computer. The computer, to me, is just a glorified typewriter. With the handwriting I have, I should’ve been a doctor. It’s completely unreadable. And you can revise really quickly on a computer. And then I get rid of the earlier versions. So I don’t have a notebook full of anything, because there is no notebook. You know, Leonard Cohen had one of the greatest opening lines ever in one of his songs: “Give me crack and anal sex.”

Yeah, that’s in “The Future.” Actually, it’s the start of the second verse.

See, there you go. That’ll get your attention. He’s trying to talk to you in an adult way. No one says to him “How could you say that in a song?” It would sound so absurd, because you’re talking to Leonard Cohen. But we were earlier than Leonard Cohen, when it came to that kind of lyric, anyway. The mythical Sixties.

What do you recall about coming up with the chord progression for “Sweet Jane”—that B minor substitution?

That’s the key to the whole song. That’s how it’s not “Twist and Shout” or any of the other three-chord songs that go that way. I remember sitting there playing this lick. To me, it’s one of the great, great licks to play. And it’s because of the B minor—that little hop to the minor chord. [The song is in D major—GW Ed.] And I said, “Sterling, you gotta hear this. Check this out.” It was exciting to do that. I still get a kick out of that. I don’t know why.

There’s something about those kind of changes. You don’t have that in jazz, really. You have it in rock. There’s just a great deal of satisfaction in going from a I to a IV chord. And I think there will be for as long as time exists. You heard those changes in folk music, hillbilly music, African music. You will always hear them. Of course, part of it is probably because that came from Africa in the first place. The real basic changes are very, very beautiful.

Was your main guitar for the Velvet Underground albums that Country Gentleman we see you with in all the pictures?

Yeah. A Gretsch. There was a guy named Dan Armstrong, and he wired that thing up nice. And then I went to San Francisco and met an electronics guy there, and had a repeater [i.e., echo] built into it, among other things. So I could seem to play faster than I really could. I made the guitar stereo, and then of course the gain went down and I had to put batteries in. I didn’t know what I was doing. I knew what I wanted to hear, but didn’t always understand the repercussions of what I was doing. Eventually it just ruined the guitar. I remember Dan took one look at it and wouldn’t speak to me for about a month. He was really upset.

I read somewhere that you took the frets off.

Not on that guitar, but on another Gretsch I had. We were experimenting around and thought a fretless guitar would be really cool. You’d have to be really good. But as a solo instrument it wasn’t a bad idea. That way you could slide into notes.

Photos from that era show you playing through a Fender Deluxe amp.

I still have it. Oh, what a great amp. But I hurt the speaker, finally, about two or three years ago. I accidentally threw a switch on my guitar that made the pickup a humbucker. That was it. They don’t make those speakers anymore.

The live set on your new album, Perfect Night, includes maybe the bitchiest song from Transformer, “Vicious,” and maybe the sweetest song from that album, “Perfect Day.”

What, you think of “Vicious” as a bitchy song? I think of it as a funny song. “Vicious, you hit me with a flower.” That’s pretty funny. Warhol said that. He said, “Why don’t you write a song called ‘Vicious’?” And I said, “What a great idea. I wish I’d thought of that myself.” It was so typically Andy. He just said, “Vicious, I hit you with a flower.” I thought it was very sweet. And also, how vicious is that? So, I added a couple of more lyrics that got a little more vicious. One line came from reading about some talk show host who was very anti gay. He told some caller, “Why don’t you swallow razor blades.” I thought, “Wow, that would make a great lyric.” So I threw it in there.

And although I said “Perfect Day” is sweet, there’s a hint of a dark side, too: “You made me forget myself. I thought I was someone else. Someone good.”

I don’t think I’m enormously different from everybody else. Everybody has had that experience in life. You’re with somebody who makes you feel like a king. Or above where you were. Your best self. [shrugs] You know, without putting too much weight on it, for Christ’s sake. But I love that song. There’s a bunch of songs I love. There’s that, there’s a song called “New Age,” and “Candy Says” which Grant Lee Buffalo just did the most beautiful version of. Which makes me enormously happy.

Is it fair to say that Perfect Night is a set of songs born of a marriage between an acoustic guitar and an amp?

It’s literally, literally fair to say that. I’d never heard a sound quite like that particular guitar going through that particular amp, using a real pickup. Not a piezo. I can’t stand piezos. So someone made me a real pickup. I plugged it into this amp I had, and it sounded fantastic, without doing anything. I was pretty shocked.

What kind of guitar? What pickup?

It’s a guitar built by a guy named Jim Olsen. An amazing guitar. And a Sunrise pickup. I’ve had acoustic guitars with those pickups in it before, but I never got this sound.

There was just something about that combination.

It’s all about combinations. As someone who’s always been in love with real old, pre-CBS Fenders, I always kind of judge things from that. That’s really the ultimate kind of experience where you just plug in and play and it’s all there: the sound, the push, the tone, the distortion, you name it. I have contemporary amps that work well for electric guitar for me. I’m a big fan of my Soldanos. And I have a few Jim Kelly amps I’d never part with. But as far as acoustic guitar goes, there’s an amp called the Tone King. They look really Fifties-ish.

The ones with the old television legs.

Yeah, like they should be in a motel. You plug an acoustic guitar into one of those and it’s astonishing. When you take an acoustic guitar and plug it into an electric guitar amp, the sound is usually terrible. There’s no bottom, or the bottom is exploding. But through the Tone King my acoustic sounded great. So the next problem, of course, is feedback. Not so much in the studio, because you can use a smaller amp and you don’t have a house P.A. system coming in on top of it.

But we did a show at [New York’s] Supper Club, and as soon as I sat down and started to play, the guitar and amp started feeding back like crazy. So I called my friend Pete Cornish, who has built me all kinds of rack systems and multi foot pedal setups over the years. This year’s problem for Pete was, “How do I get rid of the feedback and not lose the tone?” And he built me a thing he called the Feedbucker. I told him which strings were the offending ones. There were two of them. So he built me a box with two knobs—one for one string, one for the other. You get feedback and you dial it out. Oh, I love it.

A distinctive quality of your playing style has to do with the finger vibrato you often use in open chord shapes like A and D, and in other fretboard positions as well.

Oh yeah, I’ve been learning, practicing, doing that forever. Finger combos off a chord while you’re doing that vibrato. If you have a ratty tone, it’s fucked. But if you have a nice tone, you can do some great stuff. I like when you can feel it here [strikes center of chest]. Be it electric or acoustic, I think that’s one of the ways to pick a guitar out. I like to feel that vibration. But I remember when I was playing with Robert Quine, I was doing my vibrato on the strings and he said, “Oh wow, you do it backwards.” In other words, “you do it wrong.” [shrugs] But that’s the way I do it. I’ve tried doing it the other way, but the sound that I like is the opposite. But hey, to each his own.

So you do it vertically or horizontally? [laughter]

That way [mimes horizontally], or down. Very rarely up. Although I’ve been practicing that a little recently because B.B. King, Albert King, they all do it up.

Well, Albert played upside down.

Which’ll really go show you. What an amazing guitar player.

The songs on Perfect Night encompass your entire career, from the Velvets to current days. Did you plan it that way?

Yeah. I got together with this band I’ve had a while [Mike Rathke, Fernando Saunders, Tony “Thunder” Smith], and we just began trying things out in this new all-acoustic setting. I said, “Let’s throw out the old set list. Out of 400 or 500 possible songs to perform, let’s see what we come up with.” And that’s what we did.

How did “I’ll Be Your Mirror” come up?

[Photographer] Nan Goldin had wanted to use it as the title for a show she had at the Whitney Museum [in New York]. That started me thinking of the song, and I started playing it. It’s really made for that [acoustic format]. There’s not a huge difference that takes place between the versions. Except maybe it gets warmer, which is fine with me.

You’ve written songs in just about every pop genre and style at one time or another. Is that in any way an outgrowth of your first professional gig as a staff writer at Pickwick Records?

That’s really just an outgrowth of loving pop and rock. People are surprised sometimes when I tell them some of my favorite songs. I like some really stupid stuff.

Like what?

You know what I mean. Like, I wrote a song called “Banging on my Drum.” [from Rock and Roll Heart, RCA, 1976] When I say stupid, I say that affectionately. I’ve never really gotten into jazz songs. So, like, when I did a Frank Sinatra song—we did “One for my Baby” [on bassist Rob Wasserman’s Duets album], but we turned it into a shuffle. Or when we did Kurt Weill’s “September Song,” we played around with it and made it more into a rock song. [This track was part of the PBS TV show and album, September Song, the Music of Kurt Weill, and also appeared on a multi-artist disc called Lost in the Stars—GW Ed.]

Because that’s what I like. Probably one of my favorite songs ever would be Lorraine Ellison’s “Stay with Me Baby.” [A Philadelphia soul singer, Ellison released “Stay With Me” on Warner Bros. Records in 1970—GW Ed.] Lorraine Ellison. Whoa. A Jerry Ragovoy production. Wow. I was also nuts about James Burton.

And Roy Orbison when he played guitar—“Ooby Dooby.” That’s the kind of playing I go out of my mind over, to this day. The solo [James Burton’s] on [Ricky Nelson’s] “Hello Mary Lou.” Although I never went out and got that James Burton model Tele. I think it’s strung with, what? .03s? Invisible strings. I’m very happy with the guitar I have now. I always wanted one guitar that does everything, which is just about impossible. But this guitar comes real close to being the ultimate guitar.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.