Wah pedal tricks and techniques: how to expand your creativity with this classic effect

Incorporate polyrhythms, vowel patterns, and Hendrix-style licks into your playing

Invented in 1966, the wah pedal instantly added new dimensions to the sound of the electric guitar. Though simple, it offers limitless possibilities - here, we explore a few open-minded approaches to wah playing, and cover some different ways to conceptualize what it can bring to our music. And make some really psychedelic noises in the process.

Bradley J. Plunkett, though never himself a guitarist, is a bonafide hero of guitar history. He grew up tinkering with home-built radios, and was working as a young electrical engineer for the Thomas Organ Company in 1966 when his boss came to him with a challenge: could he find a good way to control the different tones of an amplifier using a potentiometer - a freely variable resistor - rather than a normal switch with a fixed set of positions?

He recounts the story in a 2005 webzine interview: “I went back to my bench and thought about it for a while and talked to a friend of mine, who was a somewhat expert on tunable oscillators - and came up with a circuit... As it turned out, it sounded absolutely marvelous.”

“It was okay when it was standing still, but the real effect was when you were moving it and getting a continuous change in harmonic content. We turned that on in the lab and played the guitar through it - this friend that I worked with played the guitar. I turned the potentiometer and he played a couple licks on the guitar, and we went crazy...”

After combining their new invention with a foot pedal from a portable organ that was lying around in the workshop, they had the world’s first all-in-one wah pedal.

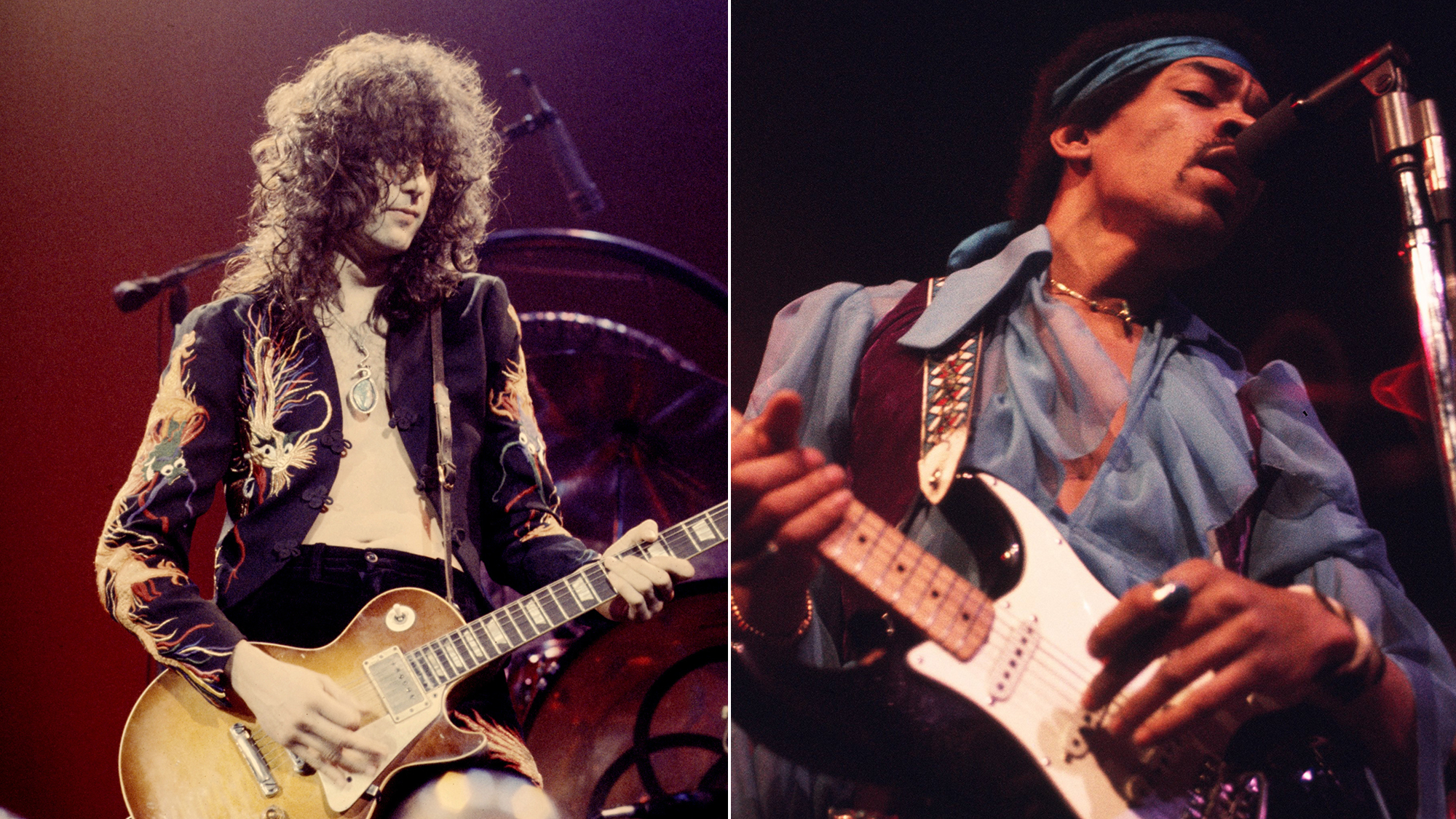

Brad describes its reception: “The thing took off like crazy... Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix... somebody said to me one time, ‘You know Brad, I think that thing you invented changed music’. It's a really fun thing to think about...but in those days I was more into electronics, oscilloscopes, and oscillators than I was into rock 'n' roll.”

Brad would remain devoted to his craft, going on to patent over a dozen more electrical innovations, while his pedal would rapidly transform the sounds of late-'60s psychedelic rock (although interestingly, the acoustic ‘bell wah’ muting technique had already been a staple of jazz trumpet and trombone for decades by this point).

Below, we explore a few ways of using the wah’s varied capabilities to bring new creative dimensions to our playing, and also go a little further into how it actually works.

Exercise 1. Emulating the tremolo

No other pedal sounds like the wah, but the wah can be used to mimic certain other effects. In this example, we imitate the ‘tremolo’ sound - a rapid volume oscillation found on many guitar amps.

If we can find the ‘sweet spot’ with our wah, we can achieve a similarly dramatic effect with a ‘controlled shake’ of the foot. While not strictly a volume oscillation, it gives a similar flavor:

And given the fine, immediate control provided by the wah, we can actually use our imitation more flexibly than the ‘real’ tremolo functions on an amp or pedal - e.g. making it wider, or matching it to whatever rhythms we may be playing. And it’s good to leave things a bit messy too - this is kind of unavoidable anyway given the pedal’s continuous response pattern.

Here, we aim for precisely three oscillations over each of the main 4 beats of the 12:8 - once ‘rock’ for each of the 12 eighth notes. Try out some familiar pentatonic patterns while holding this wah pattern constant - and hear the subtle ways it can recolor long, wide bends (a trick first explored in depth by Hendrix himself):

(Bonus exercise: separate things out, playing everything except the bend ‘unadorned’ but going hard on the wah when you do bend. Or flip this round, playing the bend straight and the rest tremolo'd. )

And try turning the drive up, and ‘unison bending’ more prominently against the 2nd string for some added dissonance - hear how the frequencies phase in and out, almost orbiting around each other at times. And similarly, try syncing and unsyncing the wah rhythm to the shapes of different vibrato patterns.

Exercise 2. Polyrhythms: ‘wah beats’ and odd groupings

The wah pedal’s power to accentuate particular frequencies effectively gives us an extra ‘layer’ of emphasis to play with. In normal circumstances, we would probably accentuate specific notes in our soloing by just playing them louder.

But whatever tones your hands may be emphasizing, your feet can independently make others more prominent by rolling the wah towards the treble - effectively, adding another ‘layer’ of control.

And how better to explore musical ‘layers’ than with some polyrhythm? This phenomenon describes the layering of two rhythms against each other - for example, when three-cycle is played over the top of a two-cycle, such that both occupy the same total time period (a 3:2 polyrhythm).

Many say it feels like being pulled in two different directions at once, although strictly speaking it’s more being pulled in the same direction at two different speeds:

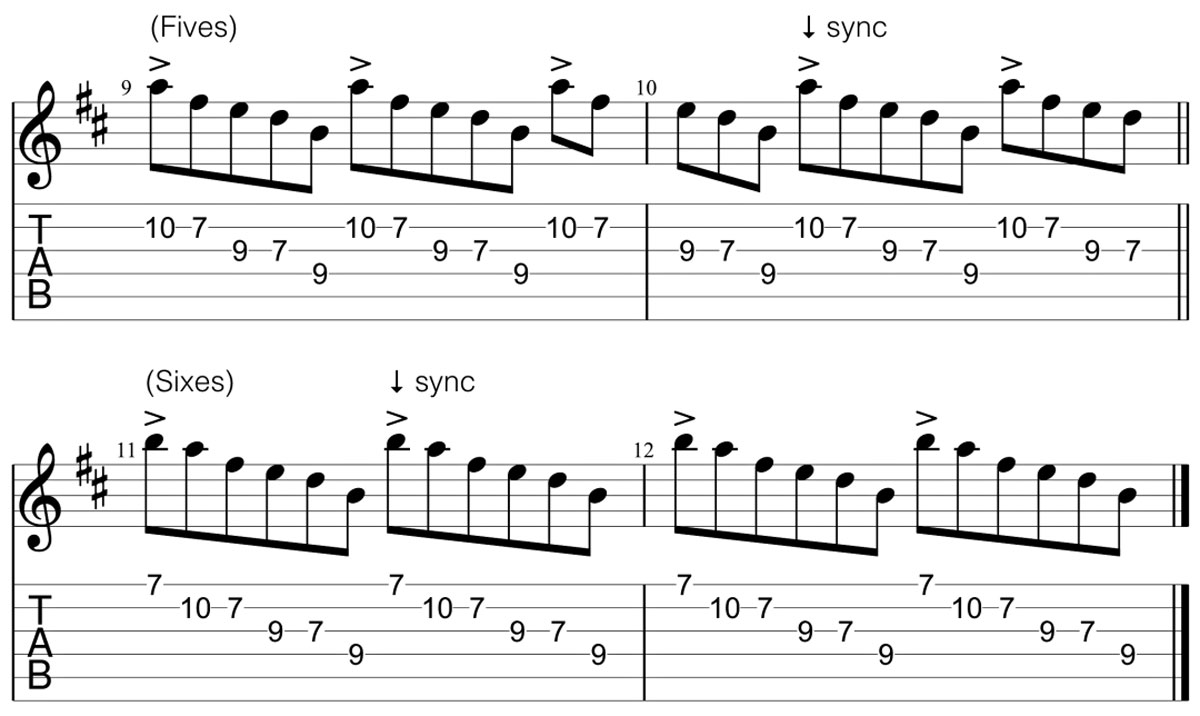

In the exercise below, the wah holds a steady emphasis pattern throughout, accentuating each main beat of the 12/8 (i.e. roll it to the treble to bring out every third note, as marked on the tab below).

You can then play other rhythmic patterns over the top, independent of the wah motion - and if you loop up any pattern that doesn’t sync to the wah, you’ll be creating a polyrhythm.

First, we play our ‘home groove’, staying on one note and syncing with the wah by playing every third stroke louder. Then, while keeping the wah pattern unchanged, we overlay a series of other rhythmic subgroupings, counting up through 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

This is difficult to ‘feel’ at first, but actually doesn’t take so long to get flowing the wah motion becomes second-nature - after all, everyone can already hum in a different rhythm to their footsteps. Really feel the wah-emphasized notes, and make sure they ring out clearly:

Take note of the ‘sync length’ - i.e. how long it takes until the two patterns both restart again at the same instant (marked on the tabs). This is key to using them effectively for longer phrases - or example, while the 3-groupings sync up tidily to the 3-part divisions of our ‘main beats’, the 4-groupings only sync up again at the start of each bar (three 4-phrases over 4 main beats).

The 5-groupings take an oddly-shaped 5 ‘wah beats’ to come back round, but the 6-groupings come round neatly, every 2 wah beats. You can employ these ideas for further rhythmic ambiguity.

(Bonus exercise: switch the layers round, i.e. pick every third note louder, and emphasize the first note of each subdivision with the wah. Or try ‘inverting’ the emphasis - i.e. deadening the first note of each pattern, etc. And to raise your improvisatory headroom, practice switching between all these approaches at will...)

n.b. If you’re enjoying polyrhythms...I have another Guitar World lesson on them, specifically covering the Ewe drum ensembles of West Africa. We demonstrate a few different ways of fitting layered 12/8 rhythms onto the fretboard, and learn about some of the cultures and beliefs behind the music.

We also discuss how to keep the learning process intuitive rather than mathematical - in the words of Ewe master drummer C. K. Ladzekpo, “Ewe drummers “don’t think...in terms of beats and numbers...we hear emotions”.

Exercise 3. Chordal control: drawing different shapes

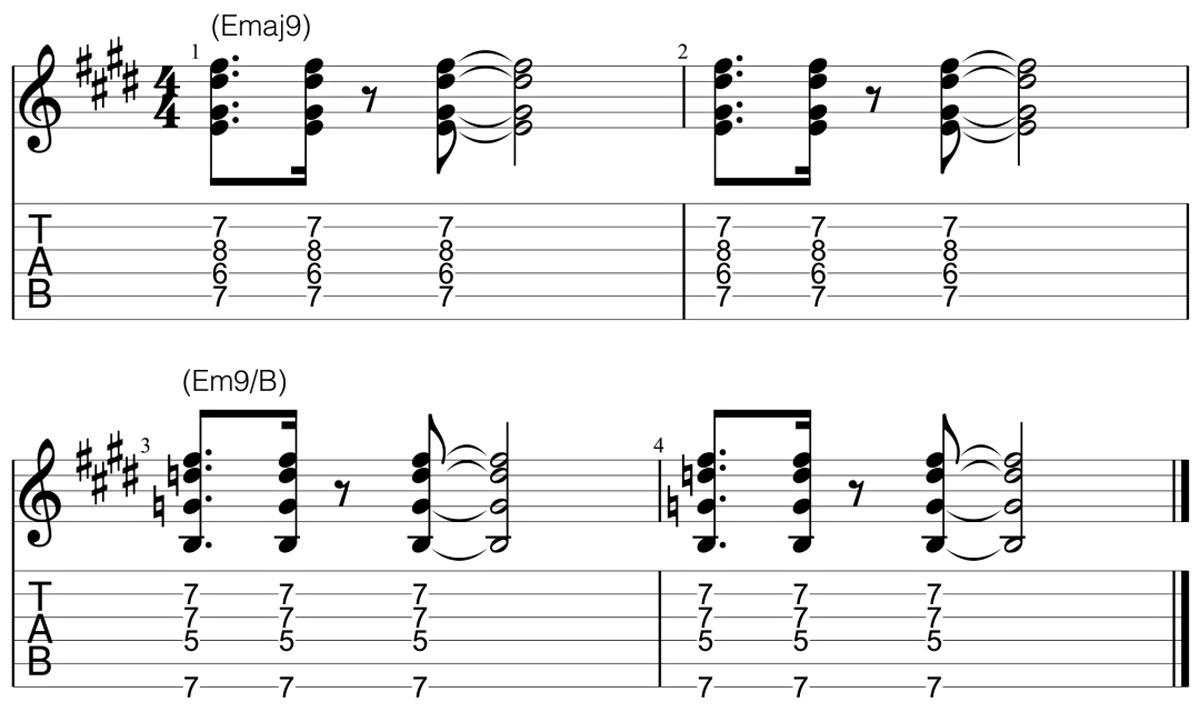

We can use the wah to ‘humanize’ our rhythm playing, drawing subtly different patterns with it to bring out the character of each chord in a progression. Use the sequence below to explore some of the fine detail and varied momentum shifts allowed by the wah.

There isn’t much point notating the precise detail of the wah movements - for one thing, different models of pedal vary markedly, as do our guitars and amps. So instead, just try to consciously draw particular ‘shapes’ over some harmonically rich chord patterns - see example voicings below.

Keep your chord choices simple for now, and notice how higher voicings will respond differently to the wah. See where you think each chord’s ‘sweet spot’ is - it will move depending on what register you’re playing in:

One trick to help really internalize things is to silently mouth along to the ‘syllables’ of the wah. Or to sing them aloud - it doesn’t matter if you sound a bit ridiculous, as this is just about building a deep intuitive connection between the wah and the voice. Probably don’t end up gurning too hard on stage though.

How a wah pedal actually works

Just as you don’t need to understand a guitar’s circuitry in order to play it, you can make a wah sing without knowing about the electronics inside it. But we may as well learn a little more about these things while we’re at it.

In technical terms, a wah pedal is a ‘bandpass filter’ - it filters the signal, only letting a particular ‘band’ of frequencies pass through. It has a ‘resonant peak’ at its ‘low-pass roll-off frequency’ - meaning that the strongest frequencies it allows through will be those just above the lowest that are allowed at all.

The pedal allows you to quickly shift where this band is in the sound (a ‘spectral glide’), from bass to treble. Contrary to popular opinion, a standard wah doesn’t actually ‘boost’ any frequencies - it just filters out others, although this of course changes the operation of other effects further down the chain. Give some shape to the science with Paul Graham’s video demo:

Exercise 4. Speech sounds & assorted noises

Above all, the wah’s vocalistic nature is what makes it unique. It’s called a ‘wah’ pedal for pretty clear onomatopoeic reasons - we’ve probably all ended up mouthing the shape of the word naturally when playing one. And the human voice is principally set apart from other acoustic ‘instruments’ by its flexibility to switch between different vowel sounds (otherwise we could ‘play’ lyrics on other instruments too).

Vowels are a bit like our ‘open strings’ - they’re unique in being produced with an open vocal tract - feel the unconstricted airflow of ‘ooo’ and ‘eee’, as compared to the closed shapes of ‘shh’, ‘ki’, etc.

The air vibrations produced by these resonant vowels are full of rich, harmonic overtones (more like strings, flutes, etc), whereas the vibrations of short consonants are dominated by higher ‘inharmonic’ overtones which die away quickly.

For evidence of this, make a short ‘ki’ sound and try and work out what pitch it is - your perception will be dominated by the ‘iii’ sound rather than the short non-resonant ‘k’. And as you already feel, the vowels themselves each demand a different shape of vocal cavity (i.e. our whole airway space).

Try sweeping through ‘ooo’, ‘eee’, ‘aaa’ while holding a steady note - feel how, as your throat opens, the sound seems to get ‘higher’, even the actual note remains unchanged.

In a sense, the sound does get higher - but only in the sense of accentuating higher overtones in the underlying note’s harmonic series. A bit like how a ‘jaw harp’ works - or when you run along the 6th string and hear all the natural harmonics come out in sequence (for a proper, in-depth explanation of overtones and the harmonic series, see my GW article on guitar tuning in fine detail):

The bass-to-treble (heel-to-toe) sweep of a wah will, roughly speaking, approximate the different vowel sounds of our spoken language. This is why it can sing, and why it can make our solos sound so much more.

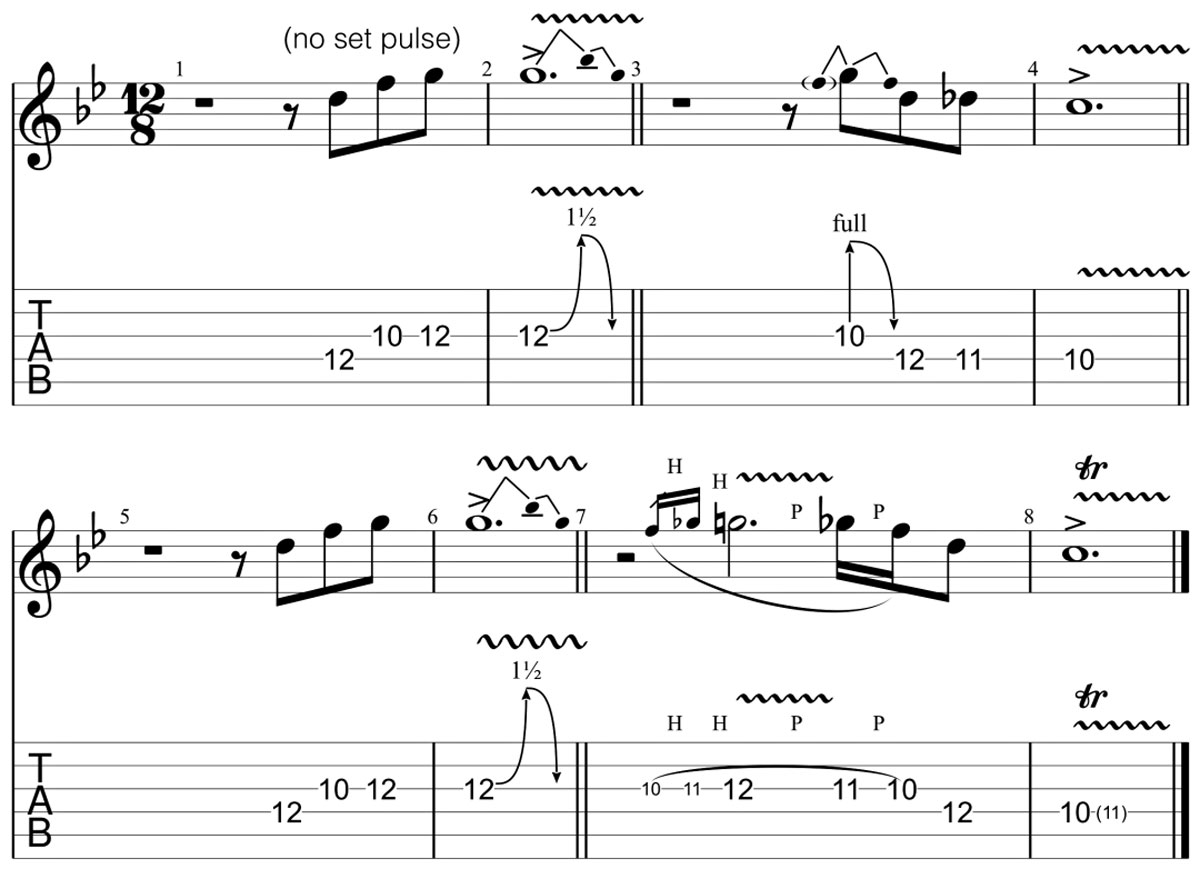

Our final exercise examines this, again turning to Hendrix for inspiration - specifically the intro to Still Raining Still Dreaming from Electric Ladyland.

Right when the first beat comes in, he briefly makes the guitar ‘speak’ with some curious bends and wah motions. We could analyse the actual notes he plays - but the reason this lick always jumps out at me is that it seems to break free of really being a melody at all. It’s like our brains start classifying it as speech instead, at least for a fleeting couple of seconds.

So the exercise below, which recreates something similar, is just a starting point for messing around, and making whatever strange noises you want to - talking, crying, laughing, etc.

Try imitating the flow of sentences you read out first (...start here), and make ‘conversations’ - just generally make a bit of a fool of yourself and loosen yourself up a bit.

Then, laugh at yourself... with your wah. (And if you really get to grips with all this, you can use your guitar itself to apologize to your flatmates when they come in and tell you to turn the noise down.)

(Bonus exercise: try different shoes, or no shoes - and then switch feet.)

Further directions

These are only a few of many different avenues for using the wah creatively. If you play with a loop pedal then a wah can be incredibly useful as a filter in its own right - it gives a strong, flexible band response, making it ideal for avoiding clashing frequencies and a ‘soupy’ overall sound in the live setting (e.g. I set mine more towards the heel to record walking basslines and chords, and then solo over the loop with a more treble-heavy wah position).

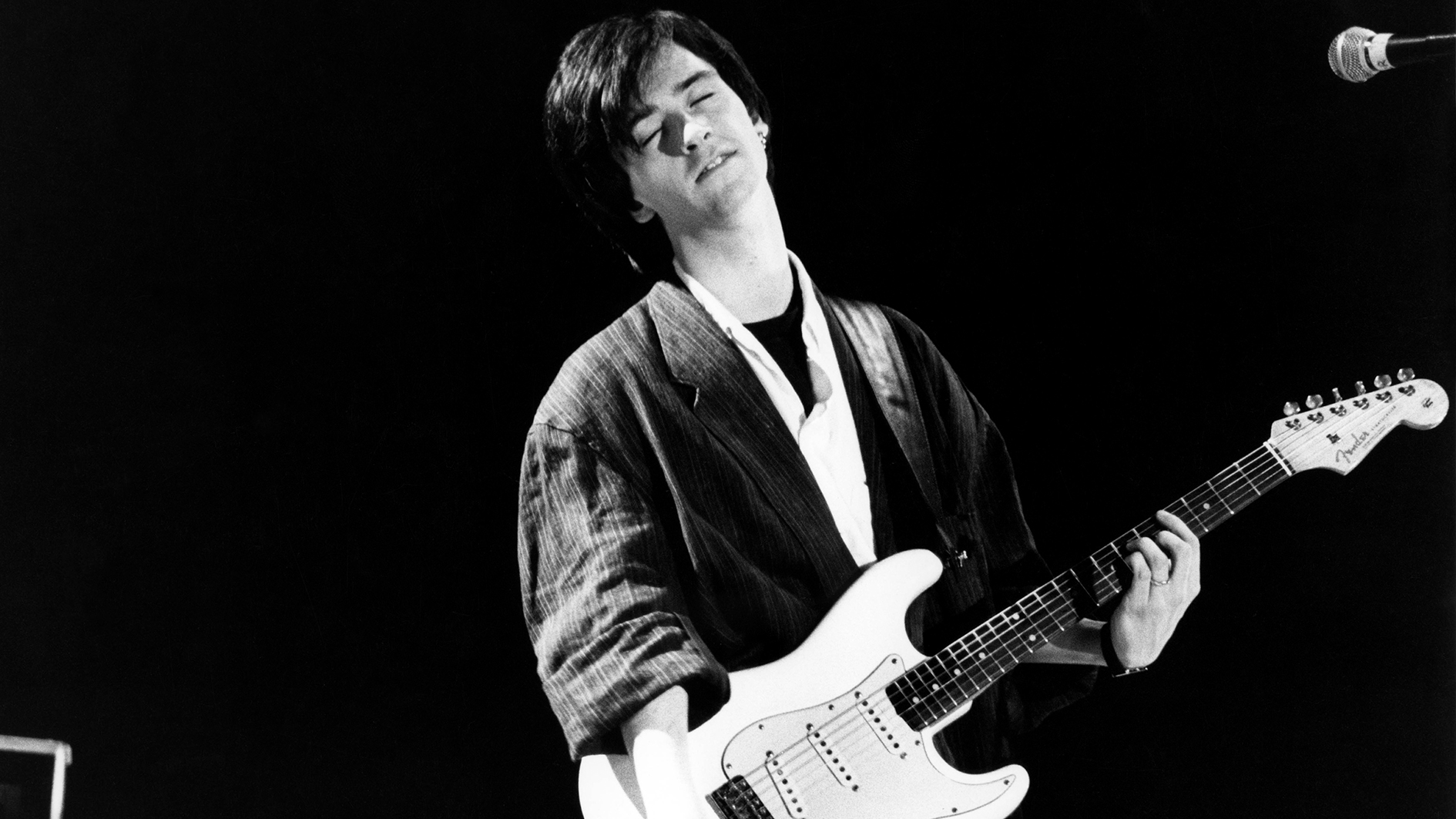

You can also try imitating a wah sound with your pickup selector - not that practical, but can be a useful flourish, and also gets you used to playing around with the different tones it brings (I often just leave my Strat’s pickups at the neck position and lazily control things from elsewhere in the chain: tone dials, volume, wah, amp dials, etc).

In the end, this lesson is less about the specific details, and more about giving the mind some structure for how it can approach a curious area of music. It’s about relaxing into the strange sounds and thinking a little differently, trying to build intuitive control over what is effectively a new dimension of sonic expression.

And of course, listen to the masters - Hendrix, SRV, Zappa, Eddie Hazel, John Frusciante, and many others.

Further listening and learning

Read Marsha Vdovin’s full webzine interview with Brad Plunkett for more on the life of this hidden guitar hero: Former UREI Engineering Director Tells the Story Behind His Famous Inventions.

Delve into the natural patterns of our spoken (/improvised) language - learn about strange linguistic study fields such as ‘adjective ordering’, and understand what ‘ablaut reduplication’ is all about. It all feeds into our music!

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)