VH1 Save the Music: How to Break Away from the Open Position and Discover New Chords Higher Up the Neck

Hello, everyone. My name is David Haiman, and I teach guitar classes to fourth- through sixth-graders at PS/IS 180 in Harlem, New York City.

In this column, I’d like to share with you a neat, fun approach I use to help my students explore the upper areas of the guitar neck in their chord playing.

After learning a handful of stock chord shapes in first and second position — what are commonly referred to as “open” chords or “cowboy” chords — it can be liberating for your fretting hand to venture beyond the first three frets, move up the neck and get acquainted with the sweet sounds of chords played in the higher positions.

In this lesson, I will show you how to build what are called triads based on each step, or degree, of a major scale, using the guitar-friendly keys of D, A, and E to demonstrate. Each of these keys allows us to employ one of the open low strings, which we will allow to ring as a droning, unchanging bass note — what is known as a pedal tone — while we switch chords on higher strings. This approach produces a musically appealing sound, one used to great effect by world famous guitarists like Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, the Who’s Pete Townshend, Roger McGuinn of the Byrds and R.E.M.’s Peter Buck.

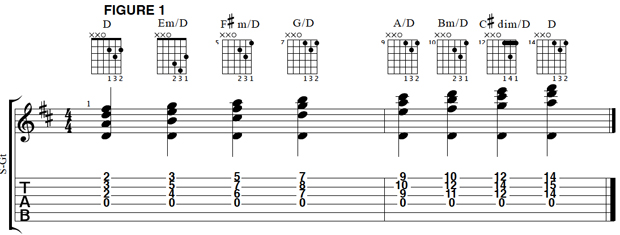

We’ll start by strumming a familiar open D chord then “walk” up the D major scale on the top three strings to generate a set of triads that reside in the key of D major (see FIGURE 1). After playing the initial D chord, switch your fingers to what would be a familiar-looking D minor shape, shift that shape up two frets, then strum the top four strings. This gives you an E minor triad over a D bass note, indicated by the chord symbol “Em/D,” which signifies “E minor over D.”

Now move that same minor shape up two more frets, which will give you F#m/D (“F sharp minor over D”). Continuing to seventh position, return to the major shape and strum. This is G/D (“G over D”). Now slide that same shape up two more frets to A/D (“A over D”), then move up another two frets and switch back to the minor shape for Bm/D (“B minor over D”).

The shape for the diminished chord, C#dim/D (“C sharp diminished over D”), is 12th fret on the G string, 14th fret on the B string and 12th fret on the high E. You’ll want to barre your index finger across the top three strings to finger this chord, as indicated in FIGURE 1. Finally, we end and resolve our chord progression by playing the original D major shape one octave higher and 12 frets above its original position. Now play the same same eight chords in reverse order.

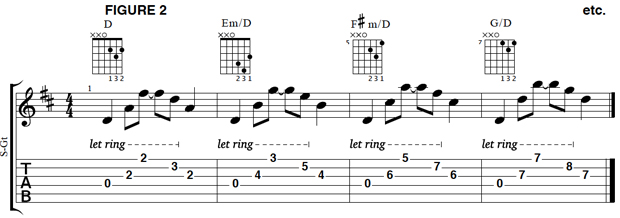

FIGURE 2 presents a musically interesting way to play the chords from FIGURE 1 as arpeggios, or what are commonly referred to as “broken chords,” letting the strings ring together as you pick out the individual notes of each chord to create a nice flow of notes. I leave it to you to continue the pattern up the neck with the remaining chords you’ve just learned.

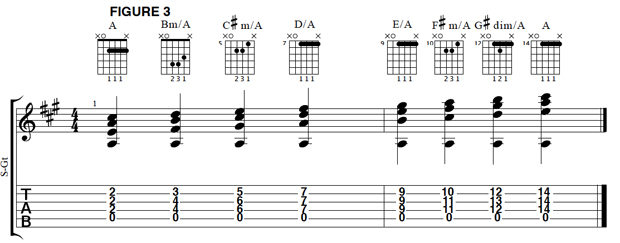

Now let’s try doing the same thing in a different key. FIGURE 3 shows a similarly generated chord scale, this time in the key of A and on the middle four strings. As we had done in FIGURE 1, we’re “walking” up a major scale on three strings at the same time, in three-part harmony, while sounding a bass pedal tone on an open string with each chord.

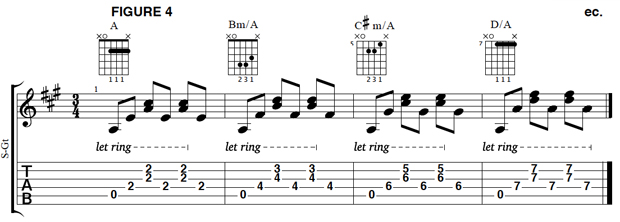

For the chords A, D/A and E/A, barre your index finger across the D, G and B strings. FIGURE 4 presents a nice, rolling arpeggio pattern in 3/4 meter that you can apply to all the chords from FIGURE 3.

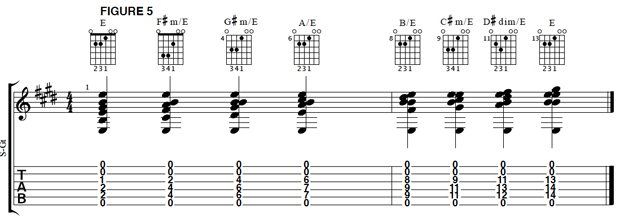

Let’s look at one more key. FIGURE 5 illustrates an ascending chord scale in the key of E major, this time with the open low E string used as a bass pedal tone and fretted notes played on the A, D and G strings. In this case we’re adding a neat twist to the proceedings by additionally including the open B and high E strings as pedal tones, along with the low E. Doing so creates a set of very rich-sounding, shimmering chords that include added “color tones.”

Try coming up with your own variations on these arpeggio patterns, and see what happens when you mix up the order of the chords in each progression, ascending and descending. One can imagine many songs being composed this way. Two examples that come to mind are Led Zeppelin’s “Ramble On” and “Melissa” by the Allman Brothers Band, both of which use some of the chords shown in FIGURE 5. Have fun experimenting with these progressions. Perhaps your own original songs may emerge from them!

Photo: Rob Davidson

David Haiman teaches guitar classes to fourth- through sixth-graders at PS/IS 180 in Harlem, New York City.

The VH1 Save The Music Foundation is a nonprofit organization dedicated to restoring instrumental music education programs in America¹s public schools, and raising awareness about the importance of music as part of each child¹s complete education. Get involved at vh1savethemusic.org.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“There are so many sounds to be discovered when you get away from using a pick”: Jared James Nichols shows you how to add “snap, crackle and pop” to your playing with banjo rolls and string snaps

Don't let chord inversions bamboozle you. It's simply the case of shuffling the notes around

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)