Up to 11: a full harmonic-melodic analysis of Nigel Tufnel’s genre-bending Trademark Solo in Spinal Tap

How the pre-eminent guitar hero draws on classical, Indian and freeform jazz approaches to sculpt his game-changing leads

More than 35 years on from their rapid rise to stardom, Spinal Tap continue to provoke a diverse range of musical, cultural, and philosophical reactions.

Critics and scholars disagree about the true nature of the group’s creative accomplishments - while some hail the bold, genre-defying sonic directness of England’s loudest band, these voices, perhaps ironically, are often drowned out by a shrill, high-minded chorus who unthinkingly dismiss Tap’s work as immature or treading water in a sea of retarded sexuality and bad poetry.

But I, speaking as a jazz guitarist and Indian classical musicologist, can discern a rich tapestry of ideas in Tap’s music, one that these pretentious, untrained naysayers have clearly missed.

My current work involves detailed study of how Hendrix, Coltrane, McLaughlin, and other pioneering Western improvisers have drawn from the rich cultural heritage of the Indian Subcontinent. Naturally, this process has also catalyzed fresh insights into the ultimate origins of other music - chiefly, in the form of the theory proposed here.

In short, I believe there is irrefutable evidence that guitarist Nigel Tufnel’s infamous ‘Trademark Solo’ not only borrows from Bach and modal jazz, but also that it draws core inspiration from the ancient Hindustani tradition of North India. The theory is elaborated in detail below, as I subject Tufnel’s 48-second solo to a comprehensive melodic, harmonic, and scalar analysis.

My workings, in line with the piece itself, are broken down into four sections: ‘dense chromatics & wailing bends, ambiguous melodic fragments, cacophonic feedback layers, and atonal violin scrubbing.

To the very best of my knowledge, every point of technical and theoretical analysis below is, in a literal sense, completely accurate - although the connections and conclusions I draw from them may prove more controversial. Before we embark on our voyage, let us first bask in the unpredictable, rhapsodic majesty of the Trademark solo itself.

1. Dense chromatics and wailing bends (0:11 - 0:24)

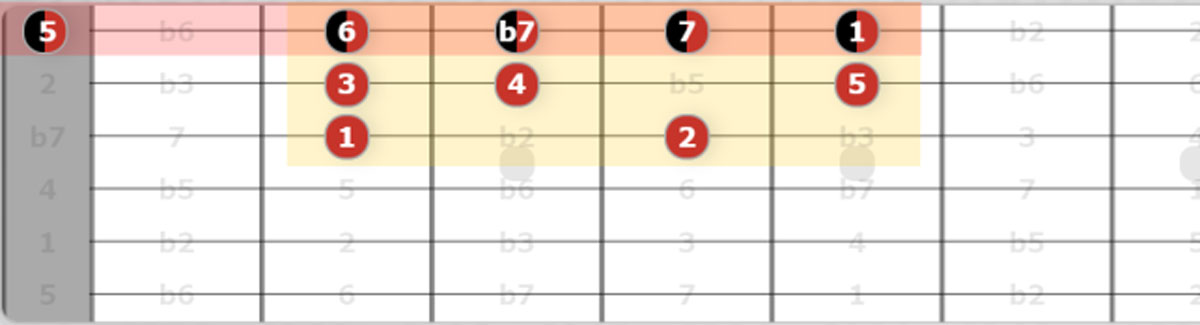

Tufnel’s composition opens abruptly, alternating complex note clusters with dramatic bends along the high E1 string. He begins by playing rapid ascending-descending flurries on frets 0-2-3-4-5 - tones which, to me, clearly imply the upper half of A Bebop Dominant, an octatonic jazz scale built from the Mixolydian mode.

Tufnel’s notes, it has to be said, match with few established Western scale forms - but slot neatly into this one as the 5, 6, b7, 7, and high root.

Observe how the patterns fit together in the diagram below - by moving the perfect 5th to the open E, he can play the majority of the scale on just one string. A full implied octave of A Bebop Dominant (1-2-3-4-5-6-b7-7-8) is notated in red, while Tufnel’s tones are marked in the blackest shade of black available in the transcription software.

In turning to this scale, he harks back to early jazz pioneers such as Charlie Christian, the guitar star of Benny Goodman’s late-1930s swing groups. Perhaps Tufnel, a leading advocate for volume, feels a particular affinity with Christian - who was, after all, one of the first ever guitarists to go amplified.

After a couple of iterations, Tufnel moves the fretted portion of his quasi-melodic fragment up a semitone, going from 02345 to 03456. Again, there are jazzy flavors: similar ascending half-step modulations form the bridge sections of many ‘AABA’ modal classics, including Miles Davis’ So What and John Coltrane’s Impressions.

Tufnel uses the device here to showcase what we might call meta-chromaticism - in other words, taking a chromatically-tinged base pattern (the 2345) and then chromatically modifying it again (by ‘pushing it upwards’ a semitone to 3456). And his use of repeated, even-numbered cells hints at Pat Martino’s octavistics concept of chromatic expansion.

This fret-shift, though at first fleeting, brings a characteristic harmonic ambiguity. His new note set (03456) now, of course, implies Bb Bebop Dominant (a half-step up from A), which turns the static open E tone (effectively a pedal point) into a dissonant b5.

He may be drawing on the Japanese Taishikicho scale (akin to the Bebop Dominant with a tritone added), perhaps a product of the band’s enduring popularity there. But this time I think the inspiration came spontaneously, from deep within.

Three high bends break up these meta-chromatic passages, introducing further harmonic complexity. First he plays 12(14), a classic whole-tone bluesy motion, but subverts its reassuring familiarity next time around with 12(13), a more mournful half-step. The third and final bend brings fresh surprise, turning into an intricate three-part motion of, roughly speaking, 11-(12-13).

This imaginative multi-step movement could be an approximation of India’s microtonal alankar ornaments, best exemplified by the legendary sitarists of the Imdadkhani lineage (read my full guitar lesson on alankar here). And interestingly, the combined fret values of the bends (11-12-13-14) mirror his original chromatic pattern (2-3-4-5), effectively transposing it upwards by a major 6th.

Tufnel’s unaccompanied, rhythmless setting - somewhat unorthodox for heavy rock - increases the dramatic resonance of the bends. His thinking here may be influenced by the famous alap-jor-jhalla sections of a traditional Hindustani recital – long solo explorations that introduce the tones of the raga in question, leaving the performer poignantly, almost painfully exposed.

Right hand analysis: It’s tempting to say that his many muted, non-resonant pick strikes are the result of enthusiasm outstripping technical proficiency.

But, given the diversity of the ideas above, we can’t discount the possibility that there are some deliberate, subtle cross-rhythms in play here, perhaps akin to jazz piano virtuoso Brad Mehldau’s famed two-handed independence. If so, any dud notes would arise not from the limits of the musician, but from those of the guitar itself.

2. Ambiguous melodic fragments (0:24 - 0:31)

[Listen from here] The solo continues with some slow, scattered melodies, seamlessly bridging the harmonic complexity of the previous section with the harsh sonic explorations of the next. Tufnel first outlines an E minor arpeggio on the E1 and B2 strings.

In terms of absolute intervallic values, the arpeggio is played in straightforward ascending order (1-b3-5), but the final 5 is in fact voiced an octave down on the open B string, effectively creating a second inversion Em shape from low to high (5-1-b3). After further shuffling these notes up a little, he then takes a different harmonic turn, bending up into a high G# - the major 3rd of E.

This fluid minor-to-major transition could again arise from modal jazz, but may also have origins in Indian forms such as Raag Jog, a bluesy creation that, in taking the notes 1-b3-3-4-5-b7-8, somewhat resembles the famous Hendrix chord (an altered dominant shape commonly voiced on the guitar as 1-3-b7-#9).

In fact, Tufnel’s combination of slow, free-time arpeggios and thick, drive-laden tones recalls Hendrix’s iconic live rendition of The Star Spangled Banner.

Though less than 20 seconds into the solo, the imprints of both jazz and Indian classical are already abundantly clear. But we should not limit our quest to these bounds - Tufnel has always been a wide musical searcher, even at one stage studying Indonesian folk music (“when the people were riding those horses out West, the cowboys would come back and sing by the campfire… [it was] very close to the original Indonesian folk…”).

So we must consider broader possibilities as well. Perhaps his unorthodox note sequences draw on the tight, mathematical stipulations of early European counterpoint – for example, the major 3rd resolution above is effectively a Picardy third, a tension-relieving device in use since the Renaissance.

Tufnel’s Mach period is, after all, the stuff of legend, best exemplified in the delicate, lilting romance of Lick My Love Pump, a short study for solo piano. But, in the absence of more rigorous theoretical analysis, this remains a fringe theory.

3. Cacophonic feedback layers (0:31-0:46)

[Listen from here] Next, the solo expands beyond the bounds of melody and rhythm, inviting the listener instead into the realm of pure sound. First, Tufnel emphatically pick-slides down the thickest few strings, ending with a low, resonant A tone, vibrating at 110 Hz.

His thick, overdriven tone and notoriously loud amp stack accentuate the second overtone from A’s harmonic series - namely, a higher, justly-intoned E frequency of around 330 Hz. You can approximate this effect with your open A5 and its <7fr> natural harmonic.

And while it’s tempting to assume that Tufnel’s frequencies derive from his extreme volume and its associated feedback effects, they could also come from more abstruse sources - in a rare 1992 interview for Guitar World he cites the “organic overtones” he can produce with his hair and fingers (“if it’s part of your body, it’s totally organic, and it sets off a very beautiful resonance…”)

Not content with a mere six strings, he suddenly brings a second guitar into play, roughly kicking at it with his right foot. It is, as far as I can make out, tuned to a highly unorthodox microtonal system, and its harmonic matrix arrives shrouded in heavy layers of feedback and distortion.

I can pick out distinct flavors of Bb, Db, Eb, E, and G in the overall maelstrom, along with soupy lower notes including A and E, all of which are mixed with bends and wailing A440 tones from the first guitar (unsurprisingly, Tufnel has not succumbed to the false allure of A432 - a cheap, pseudoscientific fad, beset with contradictions that would be immediately apparent to a musician of his stature).

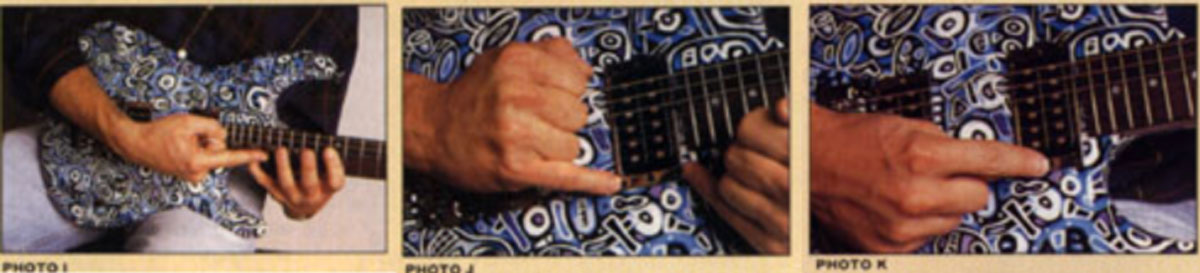

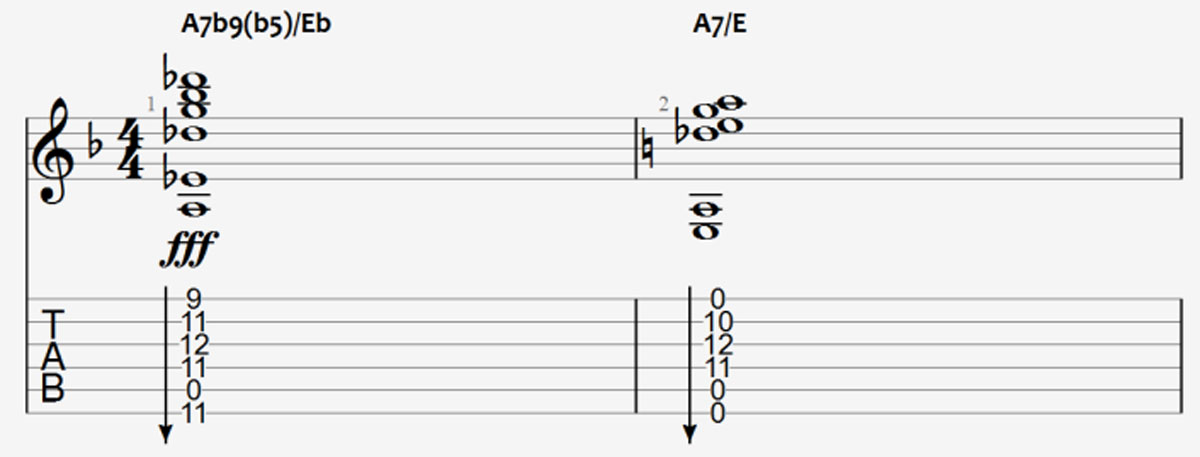

Perhaps this passage belies the influence of Smalls, who famously wore a Shrewsbury Town football shirt during his unfortunate incident at airport security. Whatever its origins, devising an exact, tone-by-tone recreation is, as yet, far beyond my ability. But you can use the chord voicings below to capture much of the core resonance and feel of this passage, even on a clean-toned or classical guitar.

The tritone-laden A7b9(b5)/Eb may suggest a heavily diminished or even polytonal species of bebop’s altered V chord, although it never resolves towards the expected I chord of D minor - despite this being, in Tufnel’s eyes, “the saddest of all keys”.

Retain his original kicking direction (E1→E6), and remember that our example is just a pale, equally tempered imitation of his microtonal sound palette.

After the first kick he pauses to roll the volume dial right up, then commences an aggressive, somewhat irregular series of further foot motions. You can partially replicate the thick, rubbery attack of his trainers with a super-heavy gypsy jazz plectrum. Also note how he (literally) sidesteps the guitar’s traditional upstroke-downstroke dilemmas, instead positioning it to allow for the novel use of across-strokes.

4. Atonal violin scrubbing (0:46-0:59)

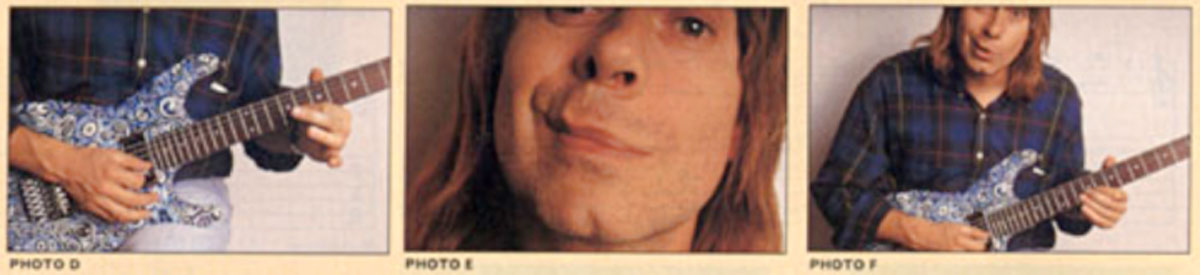

[Listen from here] Finally, the solo concludes with a nod of the head (or rather a series of impassioned, tongue-wagging grimaces) towards the avant-garde, as Tufnel picks up a violin and uses it to scrub forcefully across his original guitar.

Again, this droning experimentation points straight to India - where besides the idiosyncratic buzz of the tanpura is overtone resonance explored in such microtonal depth? Or with as many strings (16 now - just a few short of a sitar)?

Then again, his wall of sound also points to other, more modern feats of frequency architecture - notably The Well-Tuned Piano, minimalist pioneer La Monte Young’s landmark five-hour solo suite.

But while Young came to associate his composition with a precise shade of purple light, Tufnel’s chosen color scheme famously focuses on light’s near-total absence.

Tufnel’s meticulous mid-song retuning, nudging the violin’s A string slightly sharper, requires little further explanation. The act is at once touching and iconic, demonstrating not only his own integrity but also his deeply-held respect for the audience and their discerning ears.

Furthermore, his deliberate choice of such an idiosyncratically classical instrument must lend additional credence to the ‘Mach’ theory outlined above. And his use of the feet resembles the approach of church organists – surely no coincidence given the rarity of this technique in Western musical history?

But, on comparing Tufnel’s composition to J.S. Bach’s works for equivalent instruments, such as the Suite for Violin and Lute in A major (BWV 1025), it quickly becomes apparent that his abrasive sound palettes are far removed from the timbral norms of the European classical canon.

Evidently too far for some of our more closed-minded commentators - while Bach is lauded as “a colossus of Rhodes, beneath whom all musicians pass and will continue to pass”, Tufnel has been dismissed as “tasteless and gormless”, with a “musical growth rate [that] cannot even be charted”.

I remind such critics that Bach found little international acclaim until long after his death - but admittedly, what future civilizations will make of Tufnel remains to be seen.

I, for one, think that both artists can already be discussed in the same vein. At least in some respects. Consider the following passage from W. Somerset Maugham’s short story The Alien Corn: “She played Bach… in my nostrils there was a warm scent of the soil, and I was conscious of a sturdy strength that seemed to have its roots deep in mother earth, and of an elemental power, that was timeless and had no home in space…”

To me, these words also fit Tap’s infamous Stonehenge like a glove. Both draw on similarly grand temporal themes, tying them inextricably to the mysticism of the natural world (“hundreds of years before the dawn of history… hewn into the living rock”).

The band have also described the olfactory qualities of their Back From the Dead album (“woody notes…nuttiness as well”) - and who could forget Sex Farm’s earthy, agrarian lyrical metaphors (“getting out my pitchfork, and poking your hay…”)?

But the best embodiment of the Tufnel-Bach conflux is still, in my eyes, the Trademark Solo itself. Future theorists will doubtless trace the precise paths of contrapuntal confluence in more detail, but any sharp-eared listener can already feel how the two composers share much of the same essential spirit.

There’s nothing to practice - it’s all improv. You can’t practice it

Nigel Tufnel

Cellist Pablo Casals hailed the power of Bach “to strip human nature until its divine attributes are made clear, to inform ordinary activities with spiritual fervor, to give wings of eternity to that which is most ephemeral; to make divine things human and human things divine."

These elevated tributes could again apply just as fittingly to Tufnel’s solo. Likewise, the aptly-named Pitchfork Magazine‘s review of his performance evokes a charged, Coltranesque atmosphere: “Behold its closing moments, as he loses himself in the onrushing flow of sound, grimacing, even gurning as he peers beyond, straining to decipher his instrument’s deepest, innermost secrets.

Consumed by the act of improvisation, he is overwhelmed, liberated, pure – no longer a mere actor on some petty human stage, but, at least for a few fleeting moments, a living, breathing embodiment of the creative spirit itself”. In Tufnel’s own words, “there’s nothing to practice - it’s all improv. You can’t practice it”.

Importance of musical context

Perhaps a few branches of Tap’s vast stylistic tree are now a little clearer. But for now, we are still peering through thick leaves - in the end, my analysis unquestionably raises many more questions than it answers. Why the undeniable links to jazz, when Tufnel once dismissed the genre as “music based on fear…just a lot of wrong notes”? And when Tap’s Freeform Jazz Oddyssey only came about in response to his short-lived exit from the group?

The maestro’s long affinity with Indian music, though easier to trace, is no less complex, overflowing even at first glance with clashing, conflicting narratives. He famously played the electric sitar (“not as difficult…not as heavy…not as many strings”), including on Listen to the Flower People and Clam Caravan - originally titled Calm Caravan before an "unfortunate printing error."

His striking, emotive mouth movements on the Trademark Solo may draw from India’s sargam system of melodic vocalization - after all, David St. Hubbins once remarked on his fellow guitarist’s use of “barbershop raga” harmonies on the ensemble’s graveside rendition of Heartbreak Hotel (an eagle-eared observation - Tufnel’s melodic embellishment at 0:58 does indeed resemble the characteristic Ga-Pa-Ga-Pa-Dha-Ni sequence of Raag Kalavati).

These Subcontinental influences are not confined to the realms of sound. Tufnel openly cites how other aspects of Indian culture have affected his music (“I usually think of what I’ve had to eat; if it’s been Indian food…”), and once mentioned a brief discipleship under Baba Ram Dass Boot', a mysterious guru.

But while my own days studying under sitar master Pandit Shivnath Mishra typically began with dawn yoga and early-morning mantra chanting, Tufnel recalls his guru as having preached a core philosophy of “go to bed late, sleep late”.

It is unclear what else he may have picked up from his teacher, especially in the light of Tap’s Heavy Duty (“That meditation stuff can make you go blind…Just crank that volume to the point of pain - Why waste good music on the brain?”).

But the other hand, the lyrics of Rock ‘n’ Roll Creation appear to have plenty in common with the Vedic concept of nada brahma (transcendental vibration), the idea that sound is the ultimate foundation of our universe.

I recently discussed this topic with Dr. Trichy Sankaran, the master mridangam drummer of South India, covering the divine pedigree of his instrument: “Invented by Lord Ganesha, the elephant-god, or Nandi, the bull-god, [the drum] is said to have been played during Lord Shiva’s tandav creation dance, sending primordial rhythms echoing throughout the heavens as the universe was born.”

Compare this to Rock ‘n’ Roll Creation: “When there was darkness and the void…out of the emptiness…Rhythm and light and sound… Twas the rock and roll creation, Twas a terrible big bang…”

In St. Hubbins’ later analysis, the song “implies that the first thing God did was create rock ‘n’ roll…they talk about the "music of the spheres", the old Greek philosophers - they’re talking about the first thing that really happens, the beat…” Smalls elaborates: “It gave [God] the energy to do the rest of the job. What’s he gonna do, create the universe and listen to muzak?”

But other Hindustani collaborations have not gone as smoothly. The band recall the time they “had a guest drummer... a tabla player from India” called “something like Gomar, Dupar, or Gopak”, an experience they described as “awful… he kept getting carried away, and would mutter things under his breath… the geezer couldn’t count fours."

Seen this way, it is no surprise that Tufnel’s hybrid style avoids the angular rhythmic momentum and vocalized bol syllables of the Hindustani tala cycles, instead drawing more from India on the levels of the melodic, harmonic, and philosophical. For him, it seems that raga itself is the ultimate source.

Complex cultural interchange

It goes without saying that a short essay such as this can only scratch at the surface. For a fuller understanding, we must learn far more about Tap’s diverse musical inspirations, which seem to grow with each interview.

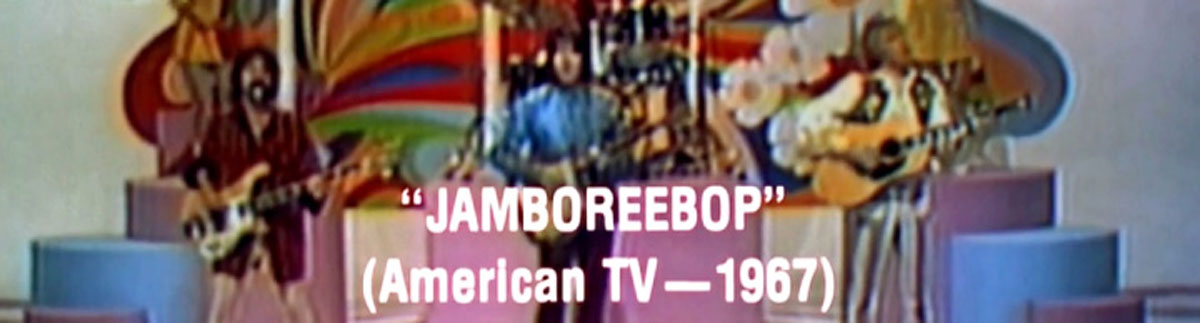

In a 2009 interview they reference recent immersions into reggae, Icelandic folk, and Brit-rap, adding new dimensions to a long career that has already spanned skiffle, flower-folk, rock ’n’ roll, psychedelia, experimental jazz, and liturgical heavy metal.

And though Tufnel mentions having composed some “trite, pornographic ditt[ies]” in the early 90s, he describes his songs of the next decade as “bardic - and, in many ways, Sephardic”, suggesting they draw not only from the wandering lyric-poets of the Middle Ages, but also from the devotional Jewish music of the Iberian peninsula.

Elsewhere he discusses the influence of “orangutans, whales, and other creatures of the night”, and recounts how he once went to Ireland, “to do some research, and saw a local rip a stag’s horn of its head, and blow it…the most beautiful sound…and really, the very beginnings of the music that inspired us."

But while these Celtic, Druidic links are already well-documented, what might he have drawn from ancient Sanskrit metaphysics? In particular, I feel his worldview rests inexorably on the concept of Saṃsāra (‘wandering’) - simply put, the cyclicality of creation. Just as the orbit of the sun has no discrete beginning or end, the sadhus of India saw that life itself is destined to loop around itself, locked in an unending cycle of death and rebirth.

Tufnel concisely elucidates this thought in saying that “when you’re dead... that’s actually the point at which you’re least dead”, and also in describing Tap as “ahead of our time, but behind the curve". Furthermore, he explicitly considers the group - which, tellingly, has itself disbanded and reformed many times over - to be “popular in the afterlife."

We can also find clues in the words the group assign to their music. Apart from the aforementioned Back From the Dead album, the title of Tonight I’m Gonna Rock You Tonight is, in a way, akin to the culturally ubiquitous image of the tail-eating snake, a self-looping, unresolved scene that fascinated Sanskrit philosophers for centuries.

See the geometry of this below - on the left, a graph in two dimensions, and on the right, a Möbius strip in three. (I’ll confess that I found the folding process pretty challenging…probably ended up working with it for about half an hour before everything came together).

Concluding thoughts

There are, of course, innumerable further horizons to explore. For one thing, many aspects of Tap’s enduring sociocultural influence have thus far gone unmentioned - in particular, the legacy of their seminal composition Big Bottom.

First released on the 1970 album Brainhammer, it boldly advocated a (literal) broadening of Western beauty standards, enthusiastically praising those who were “sitting on a great deal” long before similar sentiments became commonplace in hip-hop and R’n’B.

The song also served as the centerpiece of the band’s reformation set at Live Earth 2008 - an ecologically-inspired rendition which, fittingly, featured an army of 18 guest bassists (“physically you cannot overload the bass spectrum, it’s impossible...”).

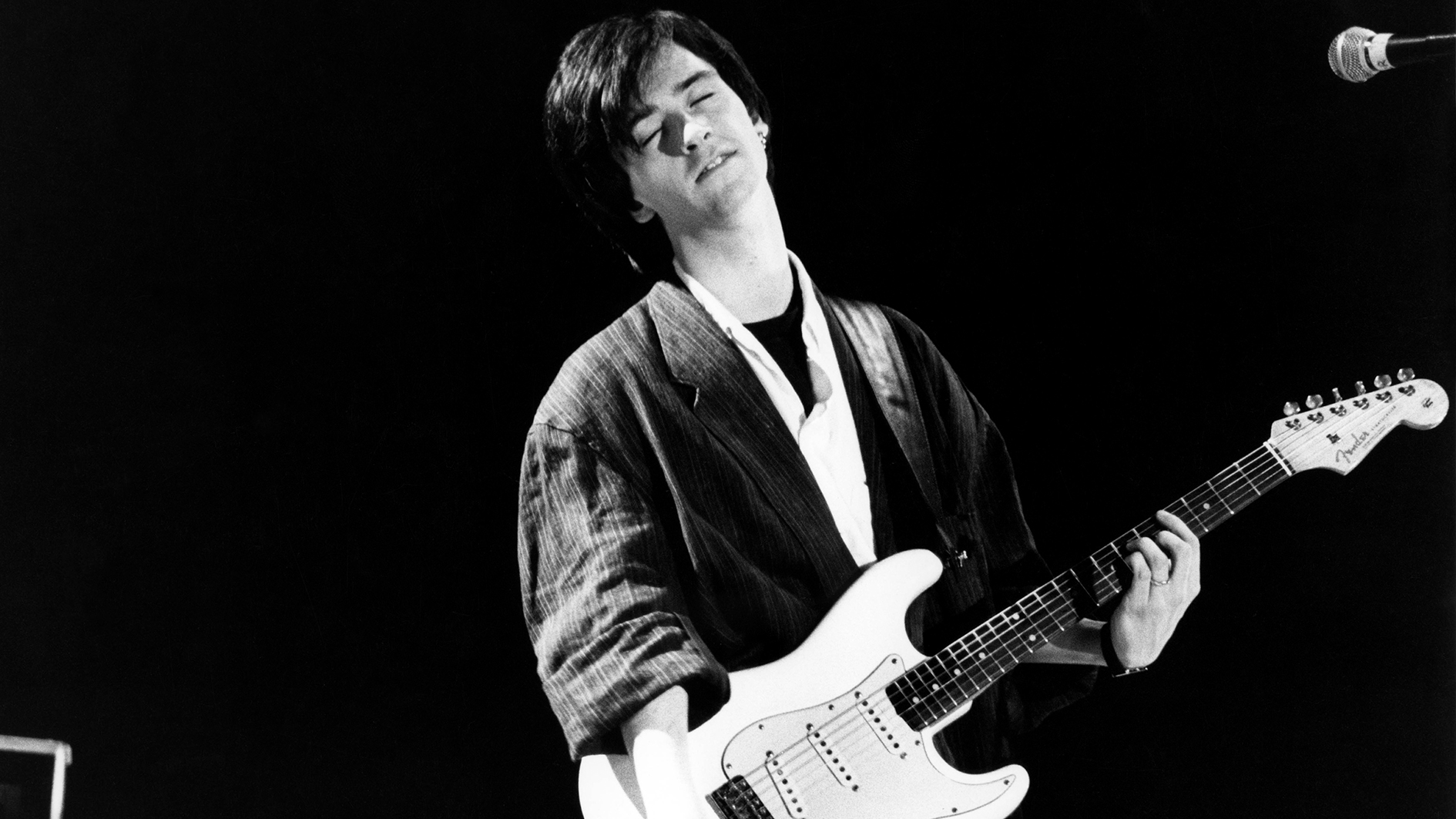

In fact, Tap have linked up with a wide range of stars over the years, including Steve Vai, John Mayer, and Elvis Costello. Joe Satriani was reportedly left “very frightened, mostly from the volume“, whereas Les Paul himself didn’t seem to be aware of Tufnel’s past work when they met on the Dennis Miller Show. But, surprisingly, his ever-growing collaboration list does not at present feature Jeff Beck, despite their uncanny stylistic similarities.

And as yet, I have not demystified the precise workings of his recent technical innovations, notably the one-piece Marshall Stack guitar and the prototype amp capo (“a big piece of rubber…pressure on the speaker”).

I have also avoided opening the Pandora’s box represented by the Nigel Tufnel Theory of Music, first expounded to my forebear Wolf Marshall in the 1992 edition of this very magazine.

Mainly because I don’t really understand it yet (“in music notation, the flat one looks like a little B [b], and the sharp one looks like crosses with a little square in the middle [#]... well my system replaces those with different-sized circles. The basis for this is Stonehenge…”).

As is by now well apparent, fresh questions arise at every turn. We should, however, pause a while before peering further into Tap’s musicological cosmos, and give our shaken, reshuffled minds a chance to settle.

Even the group’s freewheeling members advise caution here, contending from hard-won experience that rock music “will change your life, and not necessarily for the better” - presumably a sentiment also echoed by their quixotic lineage of drummers. But while we should, for now, remain patient, we can also draw upon newfound excitement for the infinite, unending nature of our quest.

In other words, we must rejoice in the knowledge that there will always be more to learn. Some, like Tufnel, may get closer than others, but no guitarist will ever truly reach their 11.

On this note, I leave the last lines to the great man himself: “People think, people create... The artistic process takes years. It’s a crackling sensation, a sort of electrical feel…”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)