“You should know the music so well that you could still play it perfectly while someone is screaming in your ear”: 15 pro guitarists share their tips for memorizing music

We've all been there. Or worse still, you're playing, all is well, and then the mind goes blank. Here, Ron "Bumblefoot" Thal, Joel Hoekstra, Marty Friedman, and a dozen of their fellow pros share their strategies for memorizing their parts

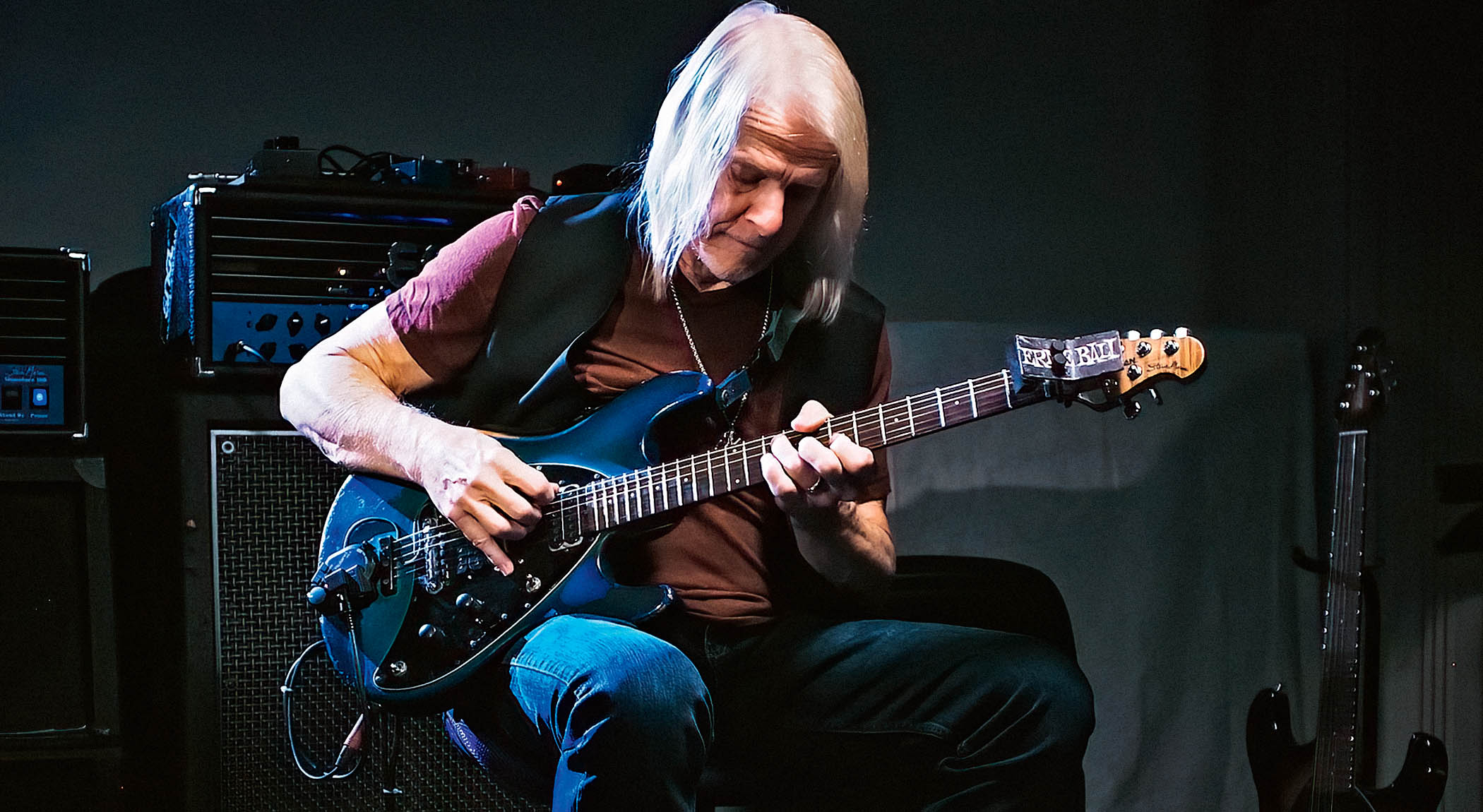

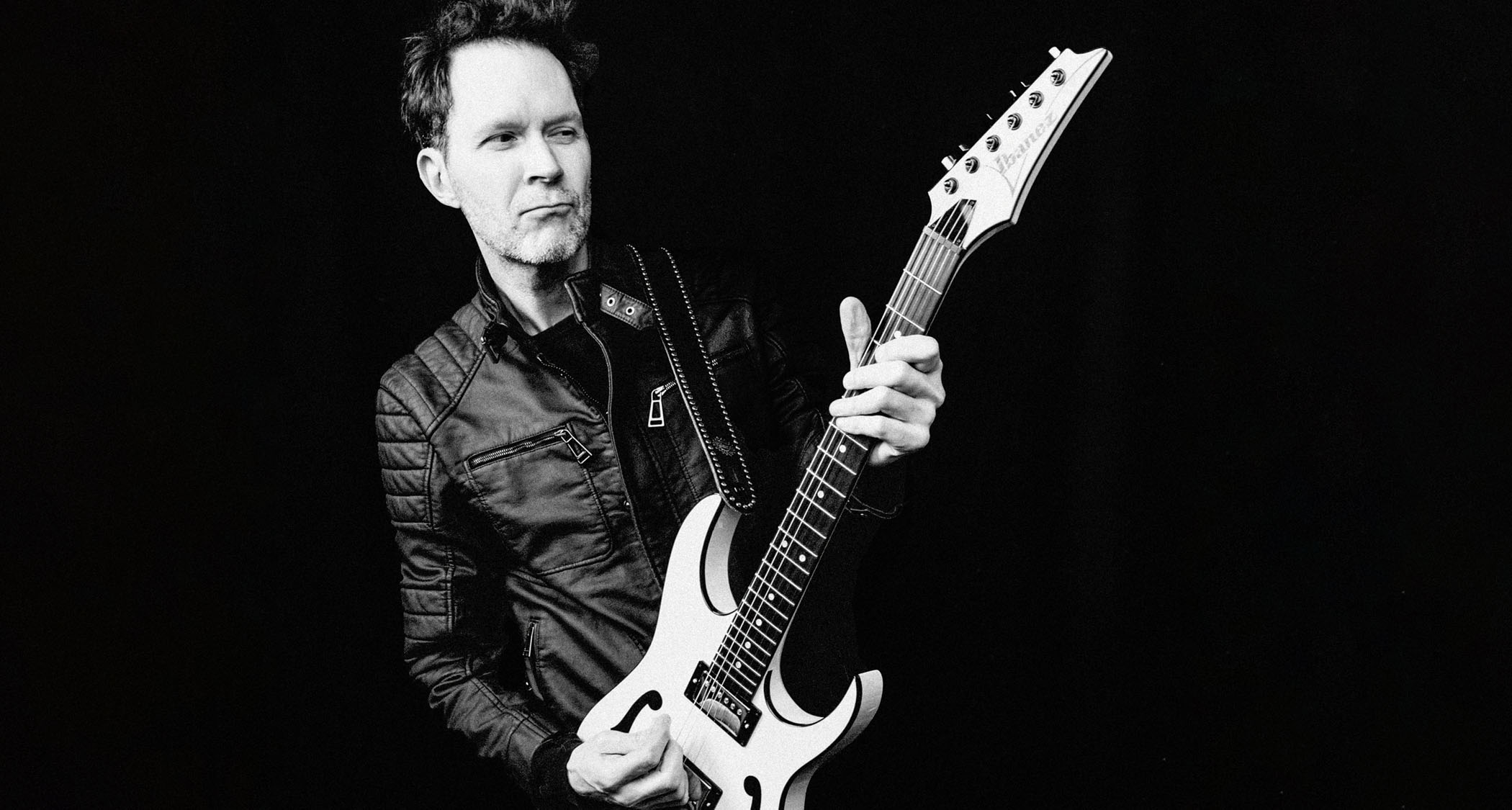

![[L-R] A composite image of Ron "Bumblefoot" Thal, Joel Hoekstra, Marty Friedman all taking a solo live: Bumblefoot plays his double-neck. Hoekstra has his white Les Paul Custom. Friedman wears a plaid shirt and plays his PRS signature model](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VPKUYFpK9bsjnQdzekheeb.jpg)

Although a mandatory requisite for being a musician, the ability to internalize music and perform it to an audience can be stressful and problematic. Yet, surprisingly, it’s a topic that’s rarely discussed.

Speaking to a roster of A-listers drawn from the worlds of rock, blues, jazz, prog, fusion, and more, it’s apparent that certain rules apply across the board, while others are specific to the artist or situation.

So, if you’ve struggled with memorizing melodies, song forms, arrangements, or parts, let the guys who do so under the pressure of big stages and highly discerning audiences help you get your own memory skills up to scratch. We put three questions to each of our guitarists, and here’s what they said...

How do you approach memorizing music for a particular performance?

Steve Morse: “Learn it by playing it repetitively (muscle memory), by hearing the music in your mind (musical memory), and by analysis (logical memory). Muscle memory is helped by starting slow and perfect, without stopping, in order to identify which sections need work. Listening to the music obviously helps memorization, and analysis should identify which keys are used, and then diagram the arrangement.”

Andy Timmons: “It depends on the level of complexity of the material. If a score is provided, I choose to not reference the chart first but learn by ear as much as possible. Of course the score is there for help with any difficult passages. I realized years ago that if I read first, it will take way longer to memorize a piece as opposed to using my ear, which has a much more direct route to my fingers. For the best way to memorize or ingrain, you must listen repeatedly. Absorb it so you hear it, not think it.”

Joel Hoekstra: “Well, nothing beats repetition. I usually eye a gig and my calendar and set the start prep date, and from then on at some point every day, that music is played. The final step is to play it with nothing else. Then, you really know the song form and aren’t relying on others.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Paul Gilbert: “Hopefully the songs are good. A good song is written with the intent of making the melody and arrangement stick in your head as quickly as possible. Lyrics can be more challenging, and can require some studying and self-testing.”

David Grissom: “Time is tight, so I listen when I am driving or walking, trying to internalize the form and parts. If it’s a one-off gig, especially if I'm busy, I write charts and load them into my iPad. I prefer to not use charts, but I’d rather do that and nail the songs than make a mess of things.”

Allen Hinds: “Well, a few years ago I used to do a few TV shows for Ricky Minor here in LA. Ricky and his staff were aware that I didn’t read particularly well, so they would send charts a week ahead of time. Now I can read somewhat, chord charts are no problem, but because we were doing TV cues and such, often there were odd meters and unorthodox notation.

“So as a matter of survival I would sift through each chart and decide where the trouble spots were, then repeatedly play through the tunes with charts until it was seamless; memorizing but still using the chart for the road map.”

Philip Sayce: “Repetition, repetition, repetition. Practice, practice, practice. Repeat! I just keep working on it until I’m not thinking about it any more. I want to get it deeply ingrained and I’m constantly focusing on how to make it better each time.”

If it's a particularly difficult piece, I spend time deciding on the best sounding and most foolproof fingerings for every note and religiously commit to them

Marty Friedman

Kirk Fletcher: “I generally listen to it a bunch. I’m a slow learner so I usually make little low-budget chord charts just to do a combination of listening and writing structures. It seems to help me.”

Shane Theriot: “I first create a playlist with all of the music that I have to learn and then just listen for a day or two without picking up an instrument. I’ll go for a run or long walk and listen passively while driving around in the car and make mental notes.

“A good amount of the learning is done for me during this process, and even if I don’t know the key of the song I can get close enough in my head with chord progressions, song structure, etc.

“A lot of my work is being done during this time. Later, when I pick up the guitar and start working on the songs, I find it easier to commit things to memory. I'll then pick out signature lines or maybe licks that need to be covered and get down the details like tones, guitars, chord voicings, etc.”

Marty Friedman: “If it's a particularly difficult piece, I spend time deciding on the best sounding and most foolproof fingerings for every note and religiously commit to them before doing loads of practicing. But for the vast majority of things, I think very little about memorizing, as the music just sticks to me after hearing it enough, and I can improvise my way out of most problems.”

Carl Verheyen: “Using my knowledge of harmony I can map out where the song is going. Modulations and simple resolutions often line up with the lyrics to provide that emotional bump in the music. An example is Goodbye Yellow Brick Road by Elton John. The verse goes: IIm7-V7-I-IV -b7maj-V7 back to I before it modulates a Minor 3rd up. The chorus modulates back to the home key.”

Nigel Price: “If it’s a jazz standard then I’ll learn the harmony, the tune, and often the words. If it’s a very ‘notey’ thing, like a bebop head, then it’s a case of listening to it at least a few times before even having a go at it. The most vital thing? Don’t leave it until the last minute. Sleep is a hugely important factor. Once you’ve nailed the material, then slept on it, it’s in there. It’s like your subconscious is absorbing it while you’re zonked out!”

Bumblefoot (Ron Thal): “I find it helps to break apart everything into ‘chunks.’ If it’s a complex line, take it in small sections, practice the sections, then practice them connected together. If it’s a song with a long arrangement, count the amount of times the progression happens and memorize those amounts as an order of numbers.

“It helps me if I take pen and paper and write out the music I need to memorize. I also play the song in different keys to really know it. And don’t always play to the recording when you practice, start playing it without it until you no longer need to hear the song as a guide.”

Brett Garsed: “The first place I start is listening to the music so I can internalize it. I have to make sure I can hear it in my head and actually have it playing in my head voluntarily. After that, it’s just a case of finding out how to play it on the guitar.”

Mike Keneally: “Decades ago, Bryan Beller told me that his process for memorizing new music which he wasn’t yet familiar with was to spend time listening to the songs over and over before ever picking up an instrument.

“This really rang true to me, and whenever time allows I'll spend days just listening to the material, at home and in the car, getting to the point where I know the song just as a song, as sound, before breaking it down and figuring out what makes it tick.

“At that point it’s just all grunt work: learning my part bar-by-bar, very slowly, internalizing all the subtleties, charting things out when necessary, and building up brain-memory and muscle-memory simultaneously.”

What do you find the most difficult aspects when memorizing new pieces?

Steve Morse: “The hardest part is creating an atmosphere of expectation and distraction, like a real gig! So you can try doing something unusual like playing it at a slow tempo (harder than it sounds). Nothing prepares you like playing in front of people though, (even if it’s your friends or family), so get used to being distracted a little.”

Andy Timmons: “Memorizing notes is one thing, remembering form can sometimes be a bit more challenging. Again, this is all solved by absorption. Listen repeatedly!”

Joel Hoekstra: “Having too many songs to memorize in too short a period of time. When I had to learn the Foreigner set in 24 hours, I worked hard for 1 hour 50 minutes and then took 10 minutes to lay down, close my eyes, and let my brain process.”

Paul Gilbert: “Memorizing involves a lot of time listening. If I like the music, then that is a pleasure. But if the writing feels arbitrary, it can be a slog.”

David Grissom: “If I start with a chart, I'm pretty much married to it unless I make the commitment to writing the chart only to help internalize the song. Oddly enough, I find doing a set of songs with similar feels and chords to be the hardest to memorize.”

Allen Hinds: “The hardest part is memorizing the forms. Take a song like Palladium by Weather Report; that’s not a typical AABA form, there are repeats with two measures added the second time. So things like that, where even a repeated section is different. Those are the hardest.”

Philip Sayce: “Maintaining focus. Shutting off all outside distractions and keeping a tight lock on my goal, which is to make the song sound like it’s breathing and living, and especially, grooving.”

Kirk Fletcher: “Not knowing how it will feel playing the music live with a band. Most of the time I learn music for myself or a sideman gig with no real rehearsal. So it’s difficult sometimes. Also if you have a bunch of songs that are similar, but with subtle changes. That can get challenging.”

Shane Theriot: “I usually don’t have any problems memorizing songs because I have done it so much. However, I would say the most difficult part can be having memorized a song and then dealing with an artist who ventures off the planned arrangement. There isn’t anything you can do for this except to keep your ears open and go with what the artist wants.”

Marty Friedman: “With my own music, nothing is difficult for me to memorize because it’s my music. What can be difficult for me is to memorize intricate parts written by other people. In those cases, I give myself very detailed mental cues as I prep, like ‘double time phrase,’ ‘first time end on F#, second time end on G,’ ‘move up after holding the long tone for three beats,’ etc - especially when I have to play many parts that are similar to each other.”

Carl Verheyen: “I find lyrics to be much harder to memorize than music. Especially if they don’t make sense! I live in a neighborhood with a few famous actors who memorize scripts on their morning walk. So I’ve learned to do the same with lyrics and chord progressions.”

Nigel Price: “With guitar I think it’s the fingering. To me, the muscle memory is the last thing to come, so it’s very easy to ‘wrong foot’ yourself, especially when hammer-ons and pull-offs are involved.”

Bumblefoot (Ron Thal): “Memorizing unusual arrangements is difficult. An extra beat of a chord in just one verse, stops and changes in unpredictable spots.. In contrast, simple songs can be difficult to memorize when there are similar chords in a bunch of songs with just slight variations in the order they’re played. It’s easy to confuse one part of a song for another.”

Brett Garsed: “Key centers, rhythmic nuances, etc. To be honest, it’s having it committed to memory and under the fingers to the point where you can really enjoy playing the music without having to think about what’s coming next.”

Mike Keneally: “For me, the rule-of-thumb tends to be the simpler the song, the harder it seems for me to memorize it. This might seem counter-intuitive, but it makes perfect sense to me. When I was learning Frank Zappa’s material it was pretty easy to internalize, because every peculiar melody or chord movement was unlike anything I’d played before. It was quicker to take up residence in my memory and stay there.

“Of course, it helped that I grew up loving the stuff, so it already felt like a part of me. In contrast, learning new Joe Satriani material was harder because his compositional building blocks are more subtle.

“In the initial stages of learning and memorizing it would be more of a struggle to internalize everything. So it’s even more important in such cases to just listen and listen again before learning to play it. Making charts when needed can help, too; they really help to keep subtle distinctions straight between different songs.”

Can you give us a few tips to help readers get better at not forgetting their parts while doing it for real, on stage?

Steve Morse: “Practice in different tempos, different scenarios, section by section, but very importantly, go over it in your head as much as you can. While you’re waiting, while you’re traveling, while you’re stuck in a line, try to visualize the music on your fretboard. Varying your approach strengthens the foundations of your approach.”

Andy Timmons: “Focus can be really challenging. The stage is such a different animal than the practice room. I have a tendency to want to engage with both band and audience (which, of course, is nearly impossible if your head is buried in a chart) so it becomes even more essential that the music is ingrained and second nature, so I can just play and project the music in the moment. Do mistakes happen? You bet. But at least I’m having a blast.”

Joel Hoekstra: “Repeat, repeat, repeat!!! I like to say that you should know the music so well that you could still play it perfectly while someone is screaming in your ear. There can be so many distractions live: a weird sounding in-ear mix, someone in the crowd doing something, or someone else in the band having a technical issue. Be mindful of playing down any distractions that could inhibit your performance.”

Paul Gilbert: “If I forget something in the song, I just hope that the band has enough musicians to cover for me, and then I’ll just turn my volume down until I find my place. In a three-piece band, there is no hiding, so I had better know the music. Or just go whammy bar crazy!”

David Grissom: “What fundamental tip helps improve not forgetting when on stage? Preparation and more preparation. Shorter practice sessions over a longer period of time if you have that luxury. Sometimes I visualize the song form as if I had a chart, and above all, if you make a mistake, laugh it off and enjoy being human!”

Allen Hinds: “I discovered the hard way; it’s one thing to know the song form while sitting in the comfort of your home, but when you step on stage or into an audition, you have to expect nerves, change of scenery, change of sound, vibe, just the moment of live performance, to put unexpected pressure on you. So you practice it 'till you can play at home, practice another five hours to account for nerves, and maybe another day for the unexpected. Because you should always expect the unexpected!”

Philip Sayce: “Certainly doing my homework. As I mentioned above, repetition and practice, rinse and repeat. Also, from time to time, if I can’t remember something for whatever reason, I’ll write out a little chart reminder and stick it on the floor. Overall, stay present in the moment and approach the music with a sense of joy, gratitude, excitement, and fun.”

Kirk Fletcher: “The best thing is being in the right headspace and relaxed. You can know the music inside and out and if you’re uptight or nervous you can mess up. Another tip I had to learn the hard way – when learning music for a gig, to really know it you should be able to play it alone, completely unaccompanied.

“I grew up playing music in church and the number one goal in church is for it to sound good and feel good. So when I played with the Italian pop star Eros Ramazotti for a tour, I had to learn the guitar parts of my friends Michael Landau and Tim Pierce, and attempt to get the right sounds, too. I learned a lot in the process!”

Shane Theriot: “I always aim to think ahead as to where I am in the song at any one time and, if possible, have a few cheat sheets or chord charts on the floor near my effects pedals. Often, especially when you are being filmed, you don’t want to be seen buried in a chart, so think of this is a back-up plan for when you don’t have enough time to commit it to memory.”

Marty Friedman: “Mentally bracing yourself for the fact that the concert itself will be an overwhelmingly different atmosphere from your bedroom, rehearsal hall, or even the sound check on the same stage, and on the same night.

“There will be tons of unnecessary sensory information bombarding you constantly, and as a consequence diminishing your concentration severely. Keeping that in the forefront of your mind during prep will help eliminate problems on the night.”

Carl Verheyen: “I mentally program into my performance practice a few places where I need to take a physical breath. This serves two purposes: first, it makes me relax before a difficult passage I’m about to play (particularly something that I always struggle with). Secondly, it helps me to visualize the overall architecture of the song and where it goes from here.”

Nigel Price: “You’ve just got to do the homework beforehand. I really can’t see any way around that (aside from taking music notation to the stage). If you don’t know it off by heart before you walk out onto the stage there’s no way you’re going to pull the rabbit out of the hat.”

Bumblefoot (Ron Thal): “The mind is in a different place when people are watching. So practice with eyes on you. Have people in the room when you run through the music, such as do an Instagram Live, something to put your brain in ‘performance mode.’ And cheat sheets with reminders about parts somewhere out of sight from the audience, if you reaaalllllly must!”

Brett Garsed: “I make sure I can perform the music without any accompaniment. If I’m relying on the drummer or bass player to cue me or remind me of sections, then I run the risk of them not playing the piece the exact same way and throwing me off. If I can play the song on my own from start to finish then I know I’ve got it under control.”

Mike Keneally: “It’s crucial to play the songs a lot before the gig, to the point where it becomes possible to shut off your brain entirely and let the muscle memory do most of the work. The muscles will retain aspects of the song far longer than your brain will, so often it’s a question of trusting that your muscles know what to do and keep the brain out of the way.

“For example, thinking too much about an upcoming difficult passage will almost always result in poorer execution of that passage than if you don’t think about it at all and just let your fingers do what they know how to do. There’s no substitute for playing a song a whole bunch of times. So make the time to do so, and the results will pay dividends for years.”

Jason Sidwell (BA Hons, MA, ALCM) was editor of Guitar Techniques, is senior tuition editor for Guitarist and has written/edited over 25,000 printed articles since 1998. He is an advisor/guest tutor for UK music academies, a director/tutor for the International Guitar Foundation (IGF) plus author of How to Play Guitar Step by Step (Dorling Kindersley) and tutorials for The Guardian and Observer. His unique Guitar Day UK teaching events have been running for over a decade. He is also a busy classical guitarist and theatre musician, has recorded with musicians such as Steve Morse, Paul Gilbert, Andy Timmons and Marty Friedman and has a broad cliental for studio guitar work.