Talkin' Blues: Rhythm and Touch

A blues phrase is made up of three ingredients: what you play (the notes), when you play (rhythm) and how you play (your touch and sound). When players focus mainly on the what—scale patterns, arpeggios, picking technique and so on—the result tends to be a solo with lots of notes in constant motion, but if you change your focus to the when and how, you can deliver a breathtaking solo while barely moving your fretting hand.

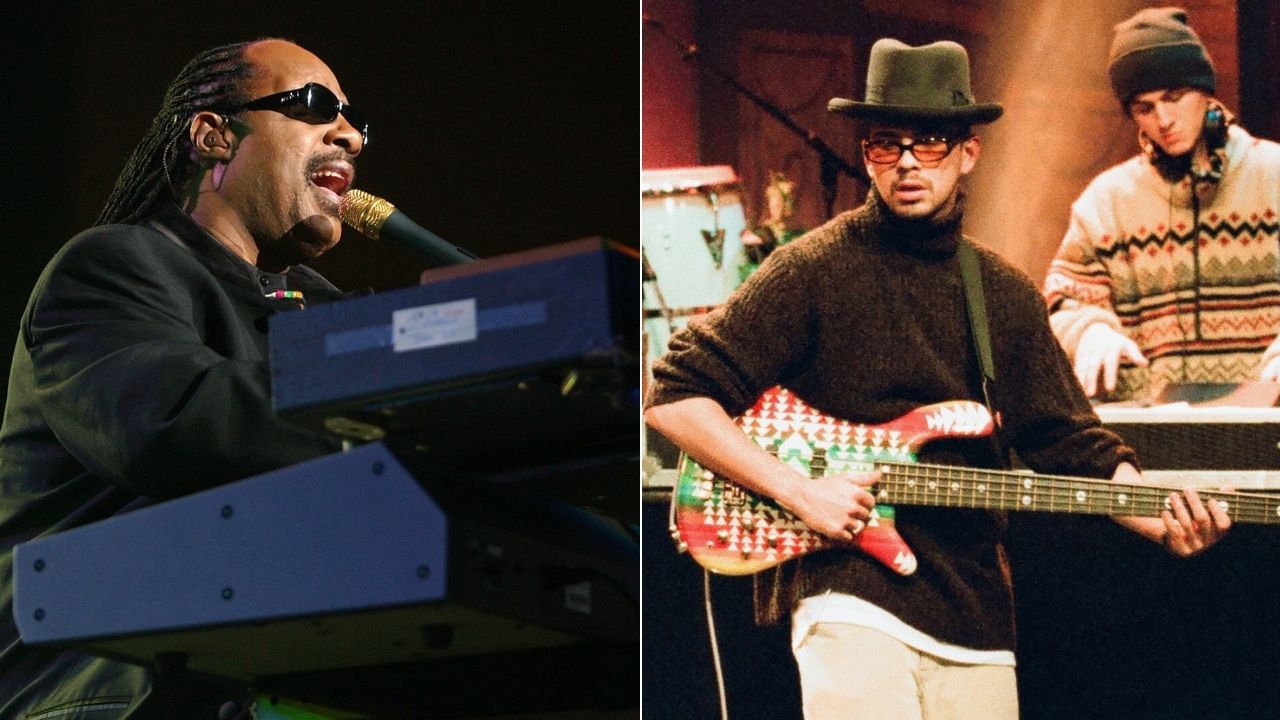

Exhibit A is “The Freeze,” a late-Fifties track by electric blues titan Albert Collins that delivers two minutes and 14 seconds of spine-tingling intensity with barely any melody at all—just four short riffs (similar to FIGURE 1) repeated over a stuttering one-chord groove. How does he do it? In terms of rhythm, Collins maximizes the sense of anticipation and forward energy by starting all phrases before the bar line, specifically on the and of “three” (“one-and, two-and, three-and, four-and…”).

The first two phrases end just before the downbeat, leaving you teetering on the edge of a rhythmic cliff, while the next two land more comfortably on the beat. Taken altogether, the four phrases create classic call-and-response symmetry. The defining quality, though, is Collins’ touch: he snaps the strings ferociously with his bare finger, grips each note like it’s the single most important task in life, and then gives you a couple of bars to think it over. The silence is as important as the notes. Equally important is the use of decorative embellishments to the notes—specifically the use of grace-note hammer-ons, string bending and vibrato—which really make the notes sing.

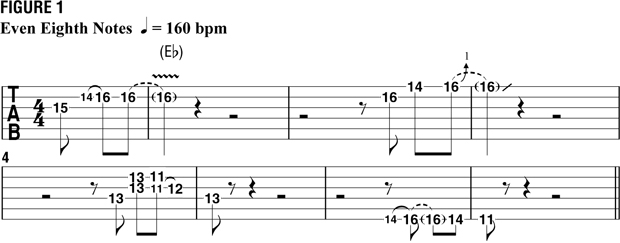

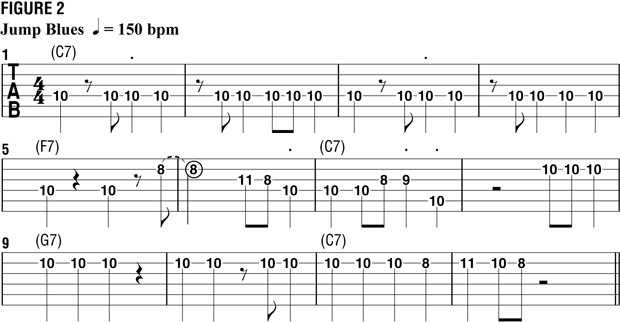

Even more rhythm-centric is the tenor sax solo on Wynonie Harris’ 1947 rendition of “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” similar to FIGURE 2. The bulk of the solo consists of just two notes—C, the root note, and A, the sixth, which becomes the ninth when played over the five chord, G7—but their syncopated energy perfectly complements the song’s message. More minimal still is Joe Houston’s 1954 shuffle “All Night Long,” where he pumps nothing but roots and octaves through his saxophone for six full choruses while varying only the rhythm, along the lines of FIGURE 3. These two examples demonstrate how effective the use of repetition can be to make a melody really stick.

In the end, it’s not a question of how many or few notes you play but rather how well you manage to convey your message to the audience. Burning licks have their place, but sometimes just that one note hit just that one way tells the whole story.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!