Lonnie Mack and the Birth of Blues-Rock Guitar

Fifty years ago, during the short interlude between Elvis and the Beatles, there was a brief sighting of that rarest of species: the “instrumental hit record.”

Riding on the coattails of surf music came a spate of non-vocal bestsellers in styles ranging from cool R&B (Booker T. & the MGs’ “Green Onions”) to funky piano jazz (Ramsey Lewis’ “The In Crowd”) to shuffle blues (Freddie King’s “Hide Away”).

Joining them was a young guitar slinger from southern Indiana named Lonnie Mack, who in 1963 unexpectedly hit the charts with his instrumental cover of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis.”

Pumping his Flying V through a grainy-toned Magnatone amp, he attacked the strings with fast, aggressive single-string phrasing and a seamless rhythm style that significantly raised the guitar virtuoso bar and foreshadowed the arena-sized tones of guitar heroes to come. Well before the term was coined, “Memphis” defined blues-rock.

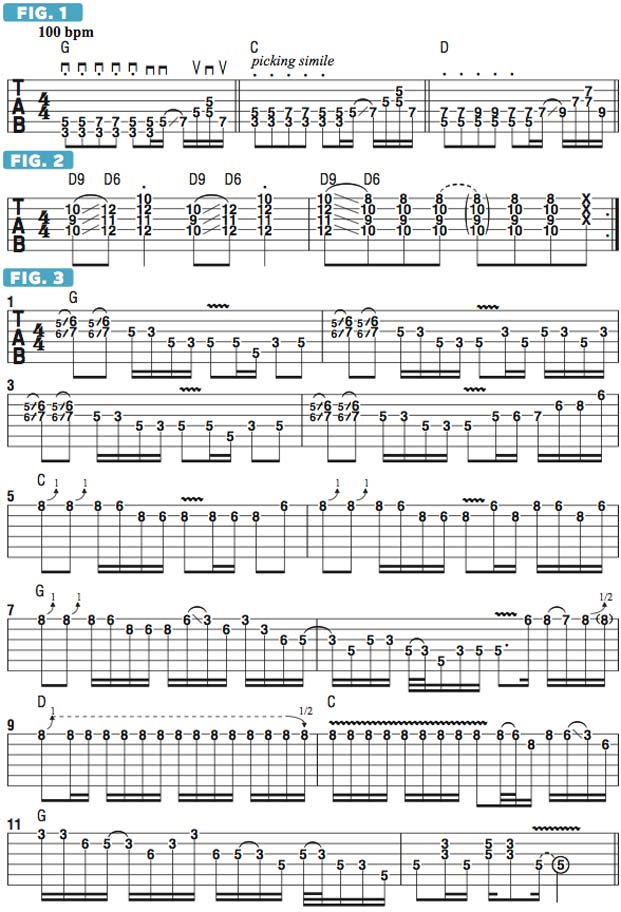

Apart from the title, Mack’s “Memphis” actually borrows little from the original. He converts Berry’s relaxed, proto-reggae groove into a driving, straight-eighth boogie (FIGURE 1 shows similar patterns for G, C and D chords that he arranged in 12-bar form) and folds just a hint of the melody into a big, bluesy chord figure similar to FIGURE 2. The highlights of Mack’s “Memphis” performance are his two solos, which showcase his driving, razor-sharp technique and impeccable command of timing and flow.

Each 12-bar chorus is a mini composition alternating between a repeated main theme and kinetic fills, similar to those presented in FIGURE 3. When playing this passage, pay careful attention to the quick position shifts; this kind of sleight of hand was a signature element of Mack’s flashy style. At the culmination of the last chorus, Mack debuts one of his signature licks, repeatedly picking a high, bent note while simultaneously shaking his guitar’s Bigsby vibrato arm (which, according to legend, was dubbed the “whammy bar” after Mack repeated the trick on his follow-up single “Wham;” you can also approximate the effect with wrist vibrato).

The British pop-vocal tsunami soon wiped instrumentals from the pop charts, but Mack’s no-nonsense, high-intensity approach remained a strong influence on generations of players to follow. You can hear it particularly in the overall approach of Stevie Ray Vaughan, an early disciple who eventually returned the favor by producing and guesting on Mack’s Eighties “comeback,” Strike Like Lightning.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!