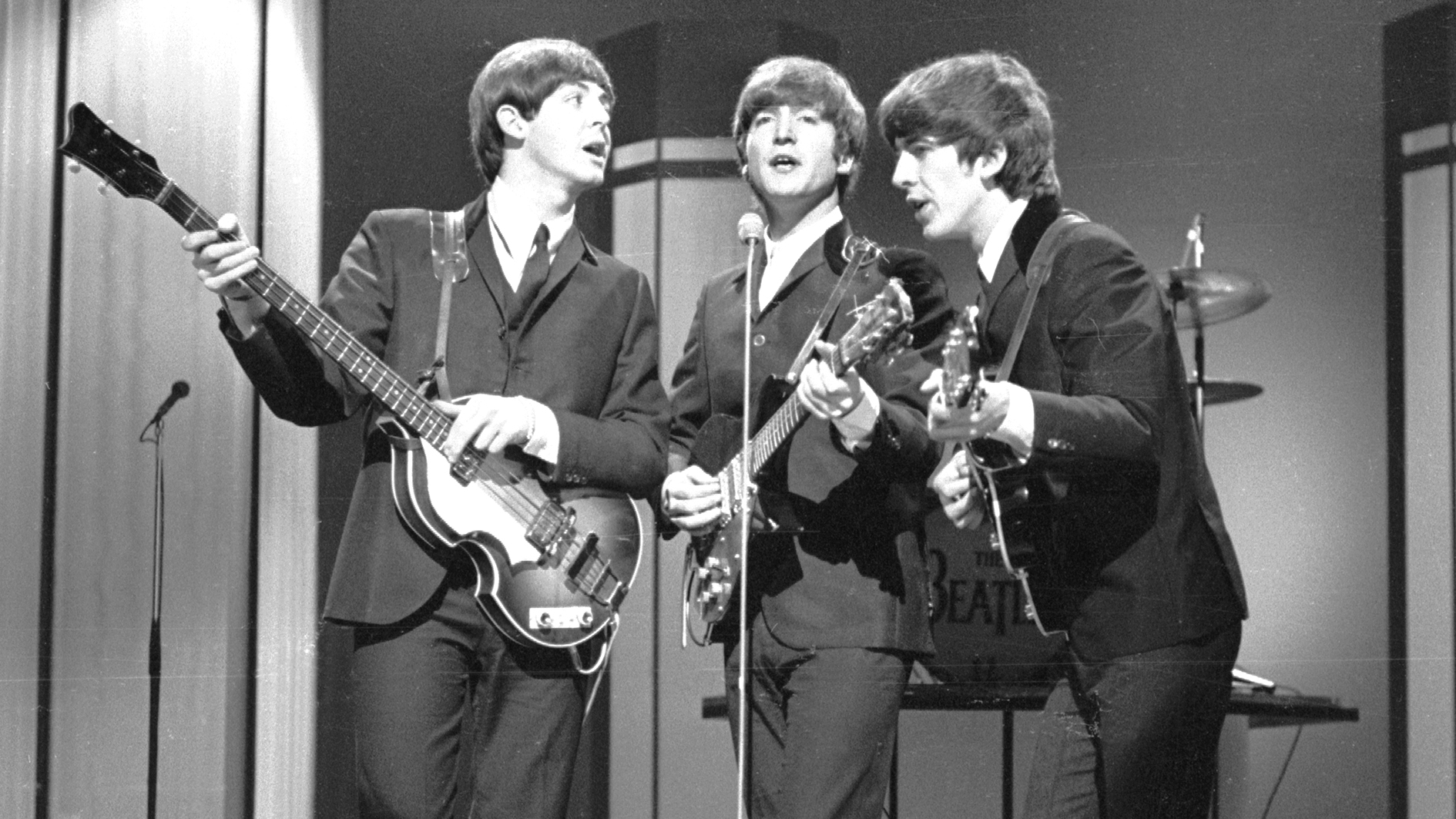

The Beatles' 50 greatest guitar songs

Charting George Harrison, John Lennon and Paul McCartney's very best six-string moments from the Fab Four's sprawling catalog

As Peter Jackson's landmark documentary, Get Back, finally sees the light of day, Guitar World is celebrating the 50 best guitar moments from the band's hit-making history.

The Beatles were such talented songwriters that it’s easy to overlook the fact that their music has some great – and occasionally groundbreaking – guitar work.

In assembling this list, we looked beyond our personal favorite songs and reflected on where John Lennon, George Harrison and Paul McCartney showed their talents as guitarists, whether in a solo, a riff, a technique or by their astute selection of instrument and arrangement.

For some songs, we’ve gone a step further and analyzed the guitar work to give you insights into the magic that makes these moments so special. Enjoy!

50. Across the Universe

Album: Let It Be… Naked (2003)

John Lennon considered the Beatles’ recording of this 1967 composition “a lousy track of a great song,” dismissing even his own work on it.

He was too hard on himself: his imperfect acoustic guitar work and vocal delivery effectively work in service of the song’s sincere devotional message, though overdubs of strings, background vocals and electric guitar obscured the delicacy and intimacy of his performance.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The release of Let It Be… Naked in 2003 set the record straight, offering a bare-bones acoustic mix of the track that even Lennon might have approved of.

49. Flying

Album: Magical Mystery Tour (1967)

The strongly pulsing tremolo on the rhythm guitar makes the instrument sound as if it’s riding slightly behind the beat, giving the song a druggy languor appropriate to its title. (In the film Magical Mystery Tour, Flying accompanies scenes shot high above the clouds).

The crystalline acoustic guitar that appears about 13 seconds in lends the song a country vibe, culminating in a tasty double-stop lick that lazily meanders down the fretboard. Heavenly.

48. Helter Skelter

Albums: The Beatles (1968)

It’s not a stretch to say the Beatles prefigured heavy metal’s doomier side with this 1968 Paul McCartney track.

For this recording, McCartney set aside his bass duties and strapped on his Fender Esquire to deliver the track’s brash rhythm work, while Harrison performed the searing leads on Lucy, the 1957 Les Paul Standard gifted to him by Eric Clapton.

But the best work here is performed by Lennon on, of all things, a bass (either a Fender Bass VI). His sloppy but inspired playing propels the song along and provides its main rhythmic interest.

47. Yesterday

Album: Help! (1965)

McCartney’s melancholy, acoustic guitar-driven ballad marked a symbolic, pivotal point in the Beatles’ career as a band in that it was their first song in which any of the members – three in this case – did not participate in the performance.

McCartney tuned his guitar down one whole step for this song (low to high, D G C F A D) and performed it as if it were in the key of G, with the detuning transposing it down to the concert key of F.

This may have been made for the sake of putting the vocal melody in a more optimal key for McCartney; it certainly made the bass notes sound deeper and richer, while the slackened string tension contributed to the thicker texture of the chord voicings.

46. For You Blue

Album: Let It Be (1970)

Written by Harrison, this seemingly straightforward blues workout in D stands out as a bouncy oddball in the Beatles’ catalog.

Not only is it one of the band’s few forays into 12-bar-blues territory; it also finds Lennon stepping into the uncommon role of lead guitarist, supplying a spirited solo and fills on a Hofner Hawaiian Standard lap-steel guitar in open D tuning.

To make things even weirder, he uses a shotgun shell as a slide. In addition, there’s no bass on the recording; McCartney performed on piano and the song received no overdubs.

45. Free As a Bird

Album: Anthology 1 (1995)

Released in 1995 as a post-mortem Beatles track built upon a John Lennon home demo, Free As a Bird makes a valiant attempt to resurrect the spirit of the group’s glory days.

While some will quibble about the lackluster songwriting, it’s hard to find fault with Harrison’s stinging slide work. Starting off with a few restrained lines, Harrison lets his playing soar on the solo, the one moment in which the song truly takes flight.

44. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

Album: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

Recorded quickly in a single session, this rocking reprise of the album’s opening track features some fiery lead guitar work from Harrison.

Written as a bookend to the album-opening title track, the reprise is both faster and a whole step lower than the original, although halfway through it modulates up a whole step. (Modulation is a technique rarely found in the Beatles compositions, And I Love Her being another example from the group’s catalog – see entry 30…)

43. I Will

Album: The Beatles (1968)

This quiet love song, written by McCartney, features only him on lead and harmony vocals, two acoustic guitars and scat-sung “vocal bass,” with Lennon and Starr providing percussion.

McCartney overdubbed, on top of his main, strummed guitar part, a second, melodic part played in a rockabilly lead style reminiscent of Elvis Presley’s lead guitarist Scotty Moore, picking out syncopated, ringing melodies built around a first-position F6 chord shape with decorative, bluesy hammer-ons from the minor third to the major third.

Years later, Cars guitarist Elliot Easton played a similar line on the chorus tags to My Best Friend’s Girlfriend.

42. The Ballad of John and Yoko

Album: 1967–1970 (1973)

In this 1969 musical telling of Lennon and Yoko Ono’s wedding and honeymoon, Lennon’s acoustic strumming sets up the song’s infectious rhythm, while his electric guitar fills play call-and-response with his vocals.

The track was written and recorded in April of that year, fresh off the sessions for Let It Be, in which the group attempted to get back to their rock and roll roots. That might have inspired Lennon’s musical direction with this track, which he closes with an electric guitar riff reminiscent of Dorsey Burnett’s Lonesome Tears in My Eyes, which the Beatles covered early in their career.

41. Yer Blues

Album: The Beatles (1968)

Lennon wrote this 1968 song as a rude sendup of the electric blues boom that had taken London by storm, but the suicidal feelings he expresses were a sincere articulation of how he felt trapped both in his unhappy first marriage and in the Beatles.

Likewise, his primitive two-note solo could be regarded as mocking disdain for the genre’s slick white imitators, but he plays the riff until it’s as raw as his emotions. He would pursue this proto-punk style of guitar playing further on his 1970 solo debut, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.