Refresh your lead playing with Vinnie Moore's guide to superimposing triads within soloing sequences

This lesson will help you cast aside your go-to licks and think deeper about tonality

When building a guitar solo, I try to take a few different approaches in order to widen its musicality and offer myself more choices than simply sticking with phrases based on the minor pentatonic and blues scales.

One thing I like to do is take a broader view of the key or tonality I’m soloing in and utilize various triadic arpeggio shapes that are native to the tonic, or “home,” tonality and its related scale or mode.

The term triad generally refers to the root, 3rd and 5th notes, or degrees, of a scale, the root being the 1st. But it can also include a sus2 or sus4 instead of the 3rd, or an upper-structure tone of a more complex chord, such as a 7th chord, as long as it’s broken down into a three-note form (usually without the 5th).

The A natural minor scale, also known as the A Aeolian mode, is spelled A, B, C, D, E, F, G. Intervallically, in reference to the scale degrees, that’s 1(root), 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7. Within this scale structure, there are triads that relate to other chords.

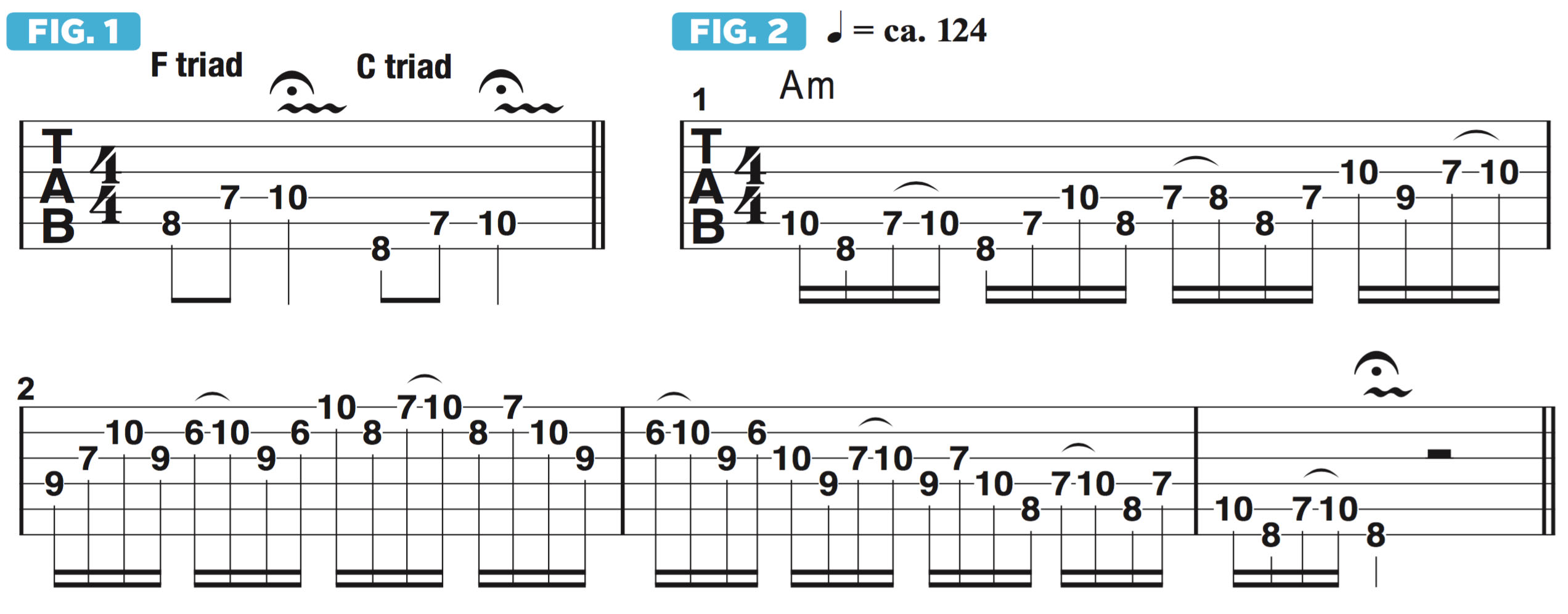

For example, Figure 1 shows the notes of the triads F major (F, A, C) and C major triad (C, E, G). As you can see, both live within the tonality of A natural minor.

These triadic forms can be found in every fretboard position. Let’s begin by building a phrase that stays within a specific one, namely 7th.

In Figure 2, I play a line built from a few different triadic arpeggio forms, or shapes, that all reside within the A natural minor scale.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I add an additional twist by playing the three-note forms in a rhythm of 16th notes, which are four-note groups, or “quads.” And so the “threes against fours” rhythmic phrasing kind of disguises the transitions from one triadic shape to another, making them less obvious.

I begin by outlining a C major triad, then, on the upbeat of beat 2, I move up to F major, and on beat 4 I switch to a B diminished (Bdim) triad (B, D, F). In bar 2, I move up again, this time to a three-note form of Fmaj7 (F, A, C, E), followed by G major (G, B, D). I then work my way back down across the strings in reverse order. Most of the notes are picked, but notice the use of hammer-ons within each shape.

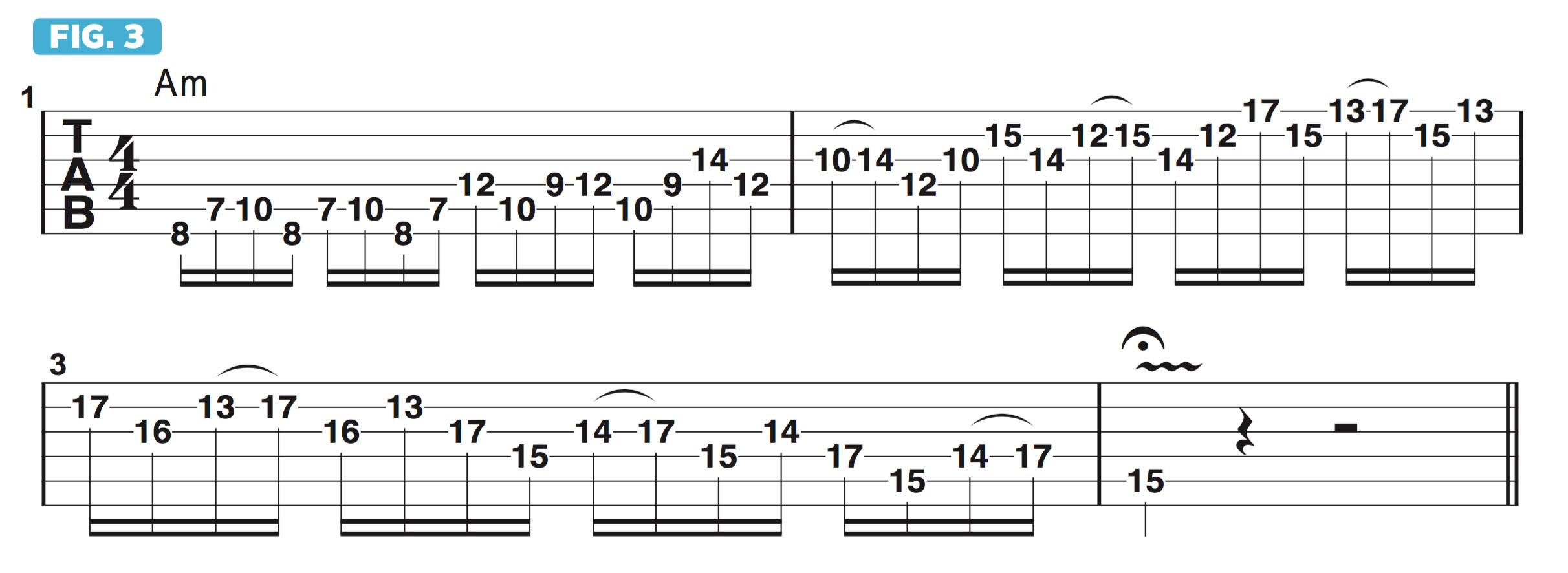

Another approach is to move up the fretboard diagonally, meaning that each new triad is initiated with a shift up to a higher position.

In Figure 3, I begin with the notes of a C major triad, but on beat 3 I move up two frets to outline G major then shift up two more frets to play a Dm arpeggio (D, F, A). On beat 2 of bar 2, I play a three-note form of Bm7b5 (B, D, F, A, minus the b5, F), followed by Dm an octave higher.

The line is then played in descending fashion, moving back down through each triad.

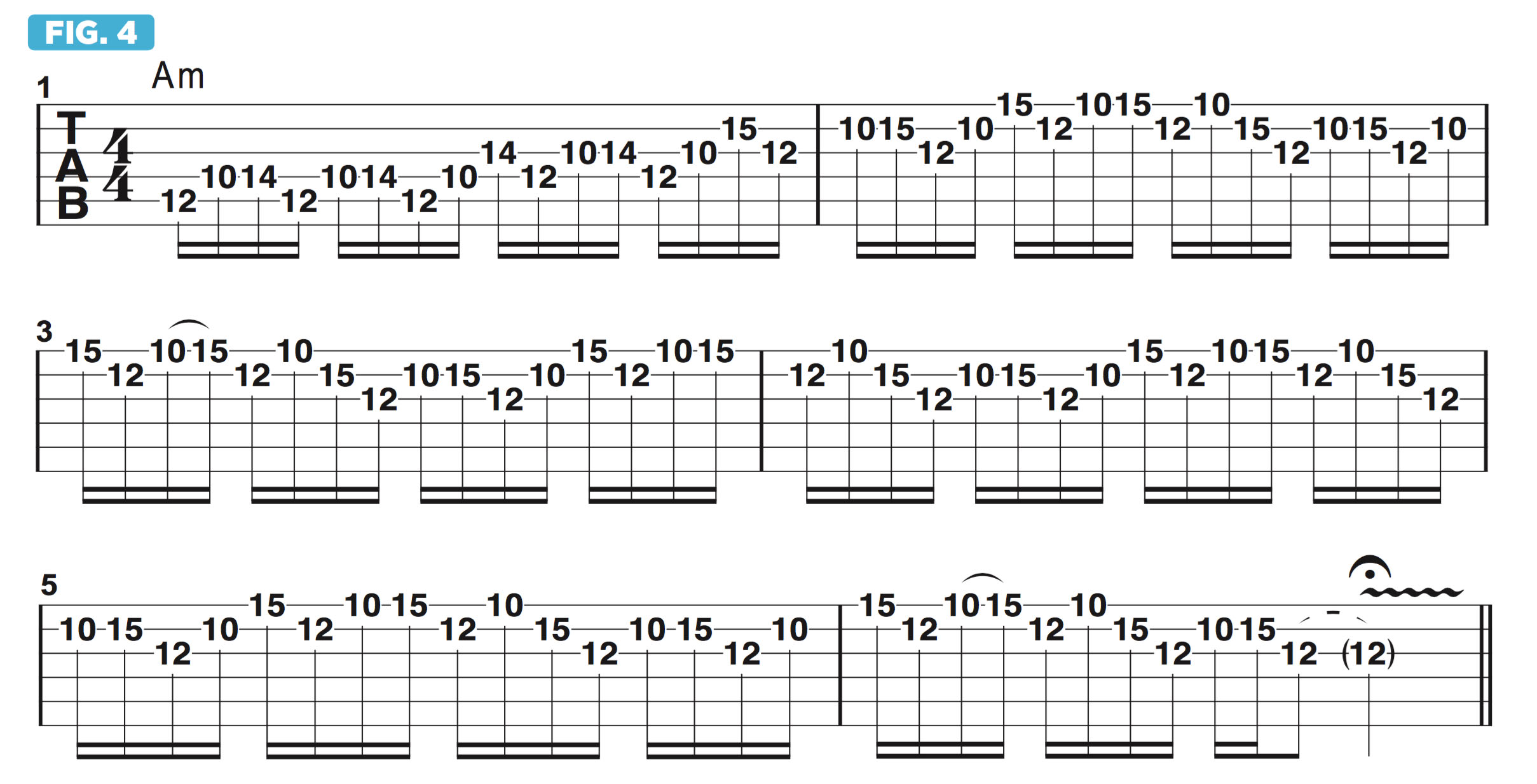

Figure 4 offers another approach, wherein I cycle between two triadic forms repeatedly, starting with Am to Dm, then Gsus2 (G, A, D) to G major (G, B, D).