Referencing the Chord Changes While Soloing

This month, I’d like to discus the art of improvising over a key change, using a modulation of chords that are a half step apart.

My favorite example of this type of modulation can be found on one of the most influential instrumental jazz pieces of all time, Miles Davis’ “So What” (Kind of Blue), which is built around a two-chord progression (Dm7 and Ebm7) that was also later used by John Coltrane for his famous composition “Impressions.”

At the time “So What” was released, in 1959, it was quite a radically unorthodox practice to simply stay on one chord and in a single mode for eight and 16 bars at a time, as happens throughout the piece, earning it the designation “modal jazz.”

Seventeen bars into the tune’s repeating 32-bar form, the key changes from D minor to Eb minor, returning to D minor eight bars later, in bar 25.

FIGURE 1 presents a condensed version of the “So What” progression, abbreviated to eight bars, with the half-step-up modulation to Ef minor occurring in bars 5 and 6. FIGURE 2 shows the bass line that I chose to play over the chord changes in the video demonstration.

To me, something to avoid doing when soloing over this progression is to simply play the same melodic lines over each chord and shifting them up a half step for the modulation to Eb minor. FIGURE 3 is an example of what not to do: the Dm arpeggio is simply moved up to Ebm to follow the key change. FIGURE 4, however, starts out the same way as FIGURE 3, but when it gets to the Ebm7 chord it ventures into new territory that is less predictable, using a common tone, F, to create differing lines while connecting them in a musical way.

While there is no great secret to playing over these types of changes and no avoidance of practice required, things are made much easier through an understanding and awareness of common tones and their applications. As we just saw, using the F note as a common tone creates a melodic thread that connects the two different chords and key centers—it’s the minor third of Dm and the ninth of Eb minor—and enables us to build lines around it, keeping the F note but changing the surrounding notes as the chord shifts underneath.

This same concept may be applied to the other common tone between these two chords, C, which lives in both the D Dorian (D E F G A B C) and Eb Dorian (Eb F Gb Ab Bb C Db) modes. In fact, if you were to only play the notes F and C over the entire progression, you’d avoid hitting any dissonant notes (I hesitate to use the term “wrong notes,” especially when it comes to improvisation, as any note can be made to work, given an effective treatment). Doing so might not be very exciting, but you should try doing it, just to get used to the sound of each note over each chord.

In FIGURE 5, the focus is placed on the C note as the common tone (it’s the minor seventh of D and the major sixth of Eb), and in FIGURE 6 I try to accentuate both common tones, F and C.

With this type of progression you can apply these principles: 1) Resist moving the exact same phrase to the new key, to avoid the sound of “following;” 2) Seek out common tones and use them to “pivot” to the new key. These techniques will certainly make your solo ideas sound more interesting, musical and creative.

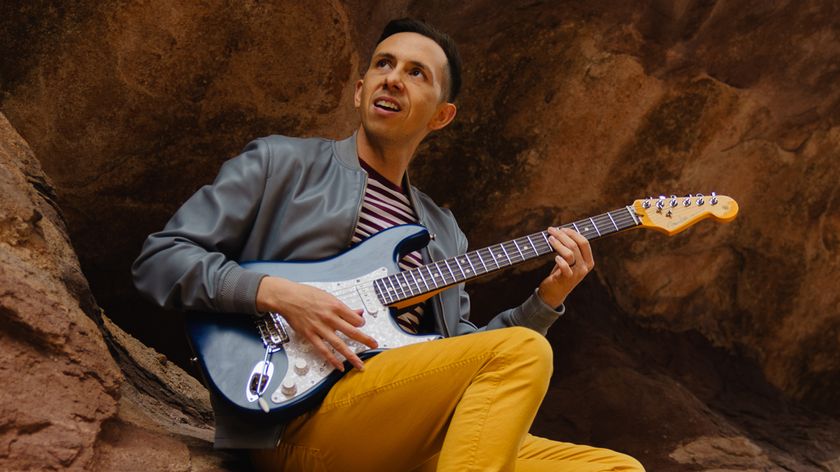

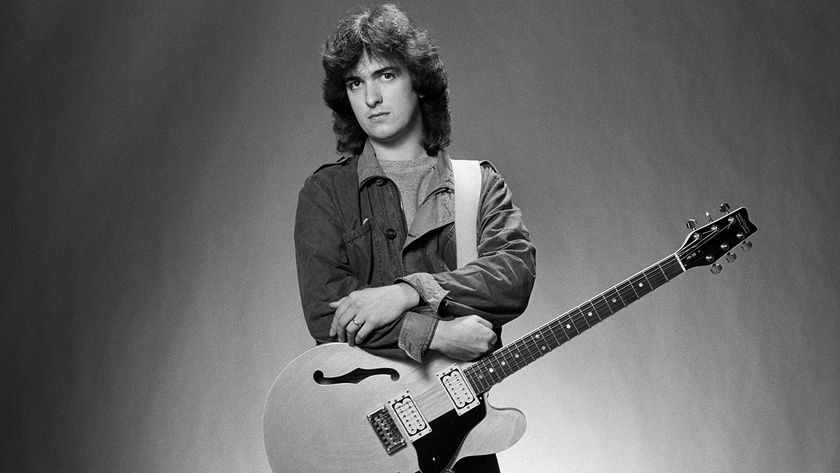

Alex Skolnick photos from lesson video by Tom Couture | www.tomcouture.com

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe-840-80.jpg)