How omitting the 5th in chords can open doors to a much wider musical vocabulary

A little chord theory can go a long way with new voicings freshening your approach to rhythm guitar

Anyone who has studied chord theory will confirm that the basis of a major or minor chord is the triad of root, 3rd (or b3rd) and 5th. Once we start altering or extending chords, though, the picture becomes slightly less clear. A sharp or flat 5th deviates from the norm, but it still refers to the ‘root, 3rd, 5th’ formula as a basis.

Sometimes, one of the notes from the basic triad is omitted altogether. Power or ‘5’ chords omit the 3rd, blurring the lines between major and minor. In extended chords (7th, 9th, 11th and 13th) the 5th is usually omitted – partly to keep these chords from sounding too harmonically ‘dense’.

The 5th is a very strong-sounding interval, lending itself more to rock than jazzy extended chords. Another reason to omit the 5th is because we only have a finite number of strings and fingers to work with and something has to give!

Ultimately, this can be a judgement call, but certain conventions have developed over time, so check out these examples to get you started.

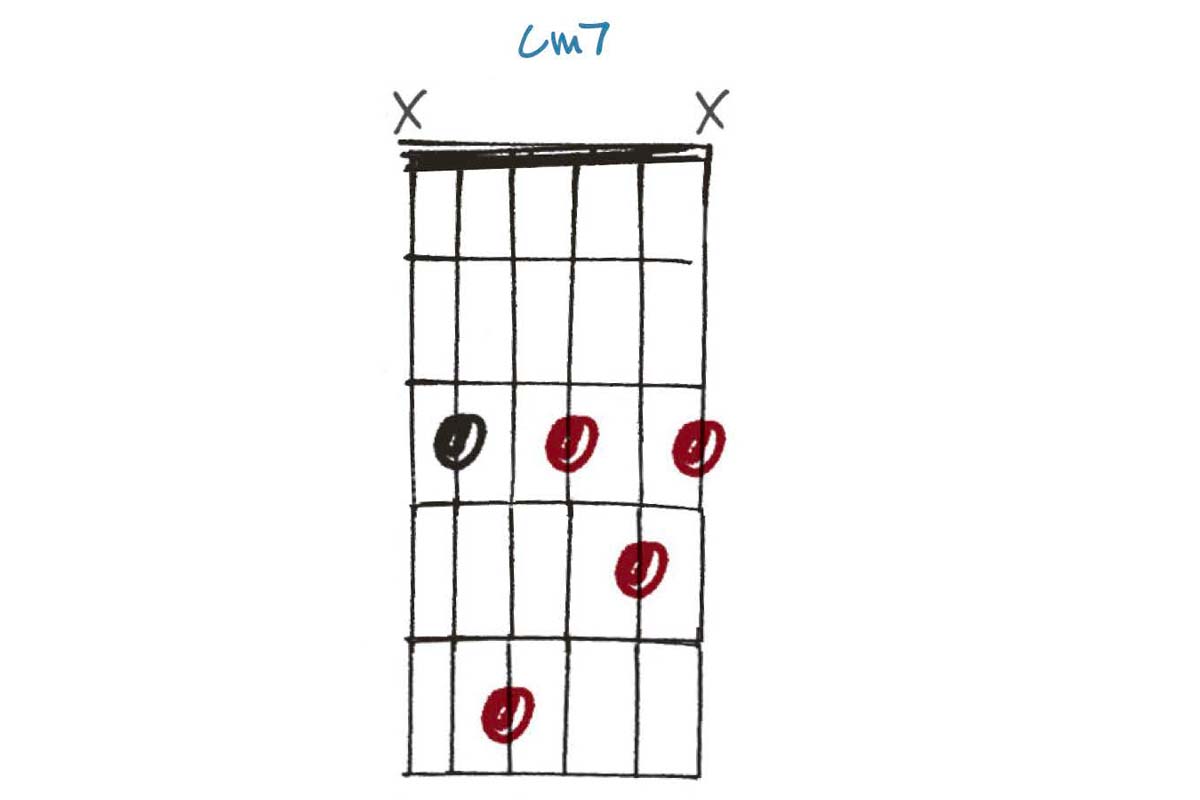

Example 1

This Cmin7 is here for comparison with Example 2: note the 5th (G) on the fourth string. This isn’t a problem at all. In fact, this shape is probably what the majority of us reach for when asked to play a minor 7th chord. However, there is another voicing available in Example 2…

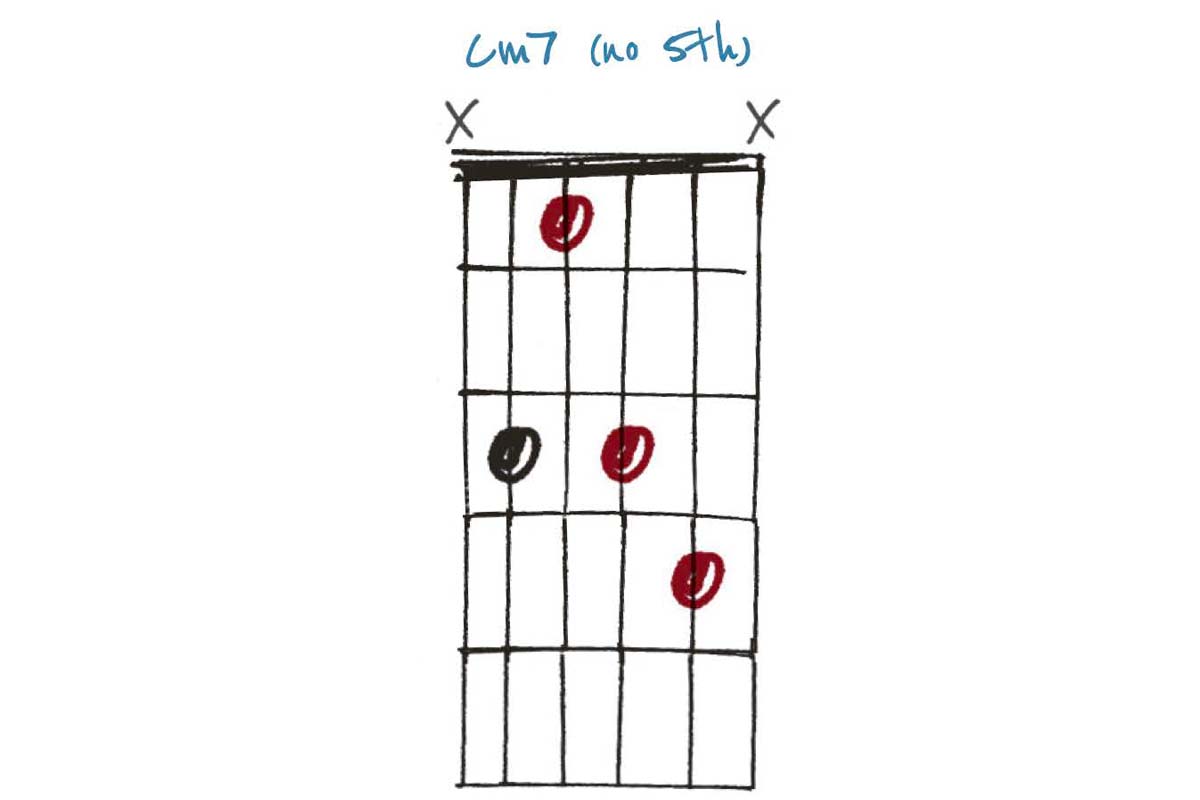

Example 2

This version of Cmin7 is somehow more ‘dark and mysterious’ sounding, less about the strong relationship between the root and 5th and more about the minor 3rd and (b) 7th. Sometimes chords like this are referred to as ‘shell’ voicings, as they outline the harmony minimally/without containing every note.

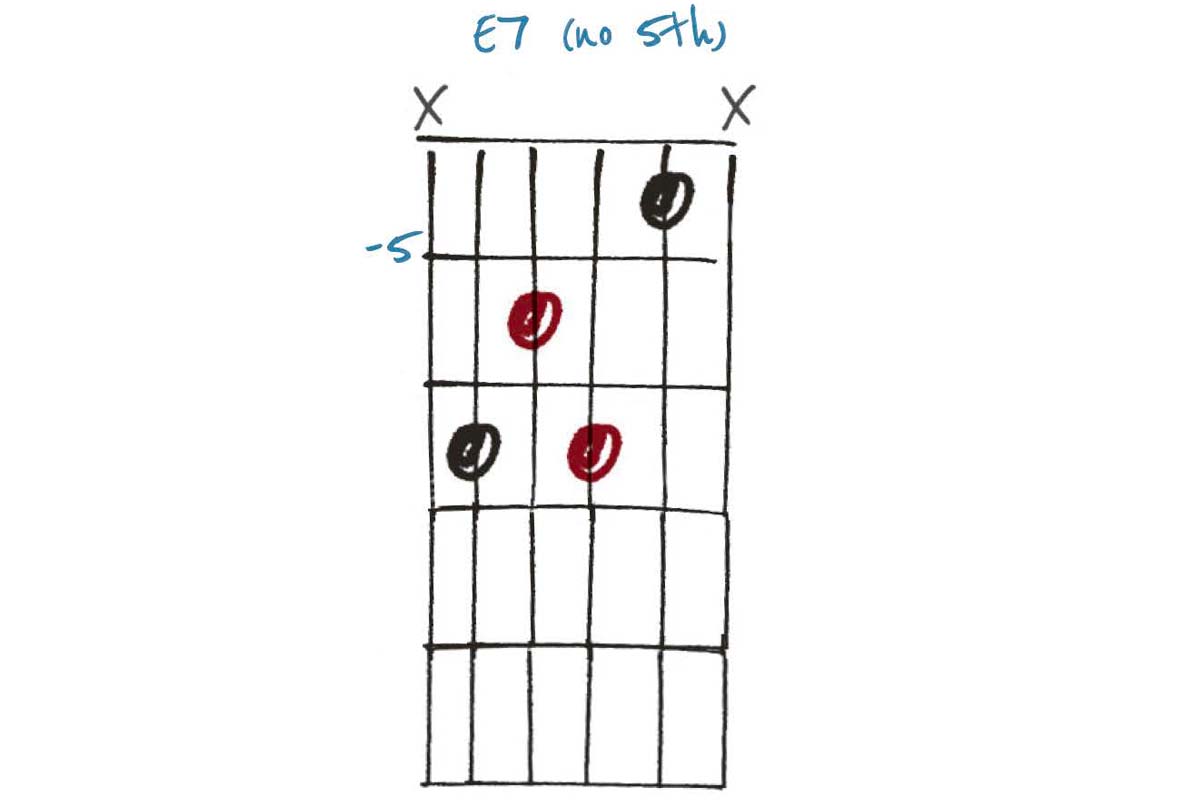

Example 3

This E7 (no 5th) gets its name from the D (b7), which in this case features on the 7th fret of the G string. There is no 5th (B) to be seen, which puts the focus on the major 3rd, b7th and roots on the top and bottom. Note this is essentially a C7 shape moved to a different position and can work at any fret.

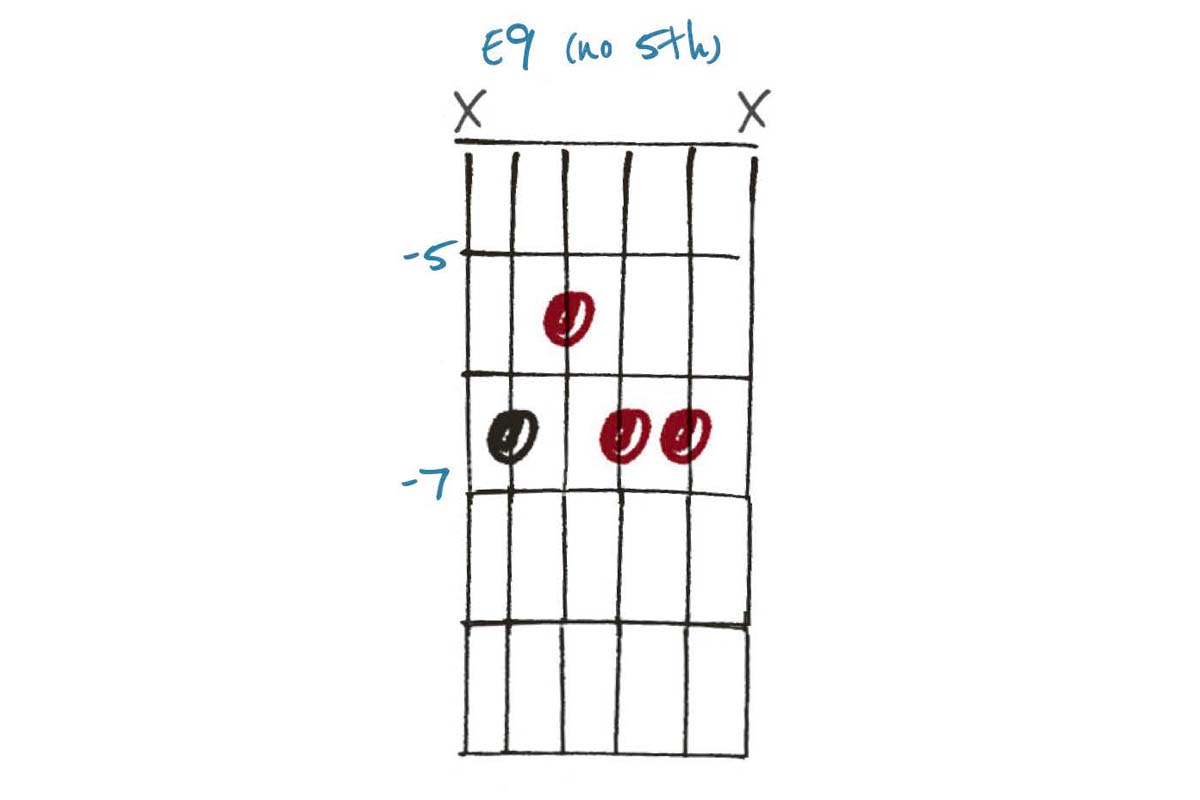

Example 4

Using the same basic shape as Example 3 but shifting the highest note up a tone to the 7th fret (F#) changes the chord to an E9 – or to be more precise E dominant 9th (no 5th), as the 7th (D) is actually a b7th rather than the D# you will find in the E major scale.

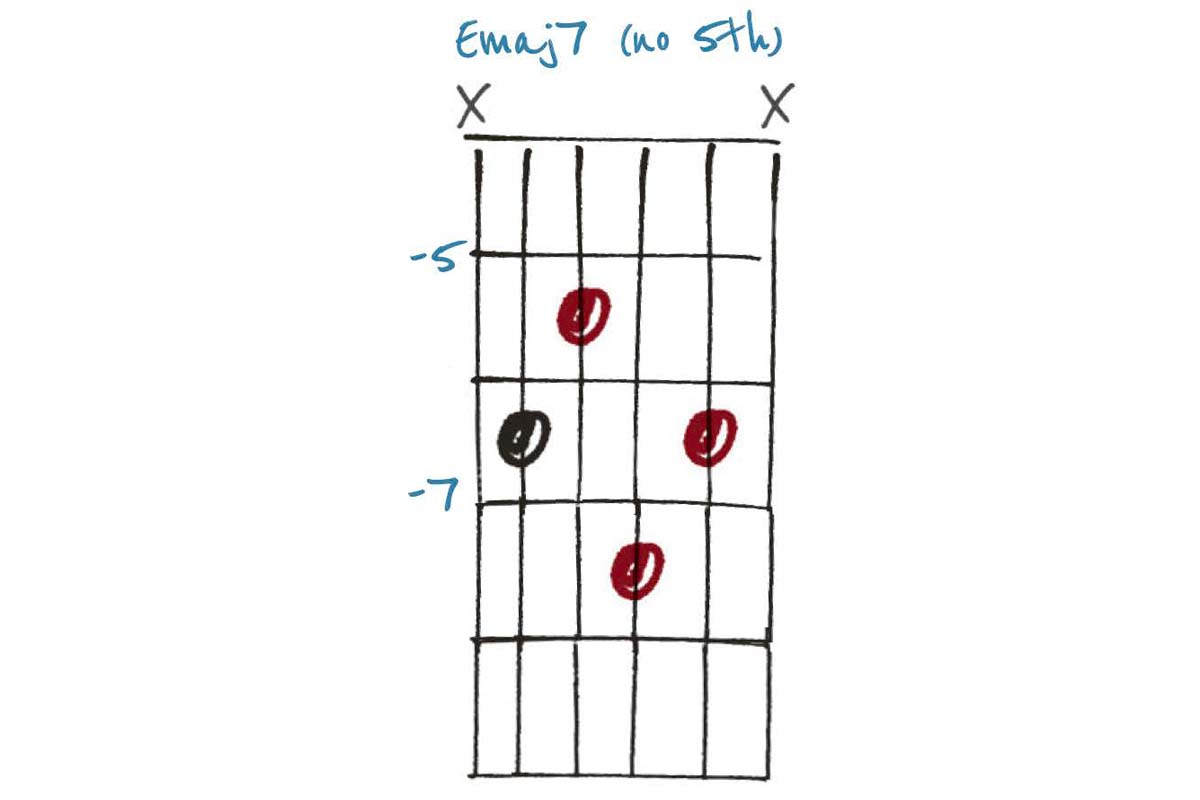

Example 5

Shifting the b7th up a semitone to use the D# from the E major scale makes it a major 7th, so this chord becomes an Emaj9 (no 5th), the ‘major’ referring to the 7th and the 9th being the highest extension – for which we always presume the presence of a 7th, or this would be an add9 chord!

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)