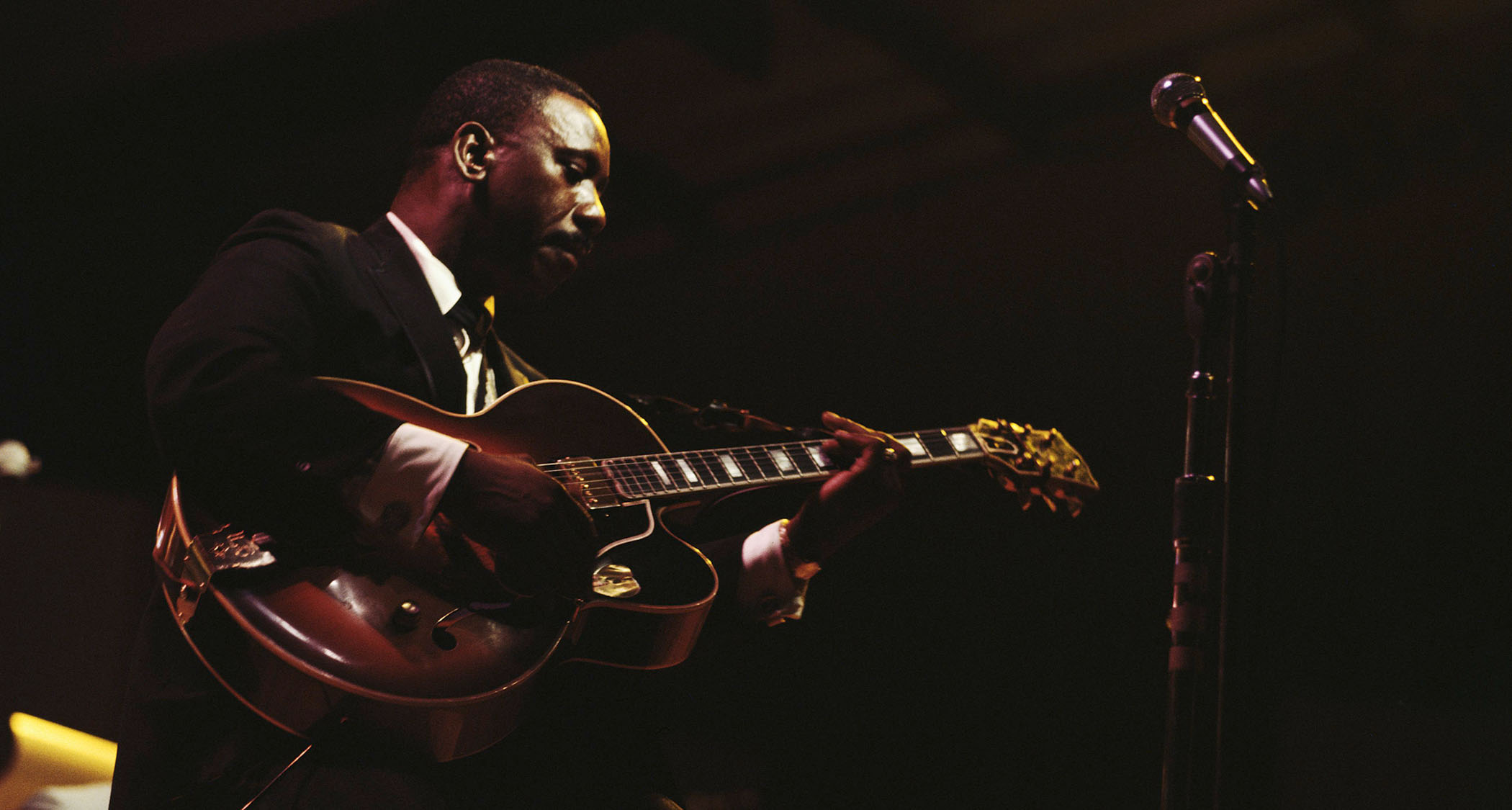

Learn the slippery soloing style of Muddy Waters

This improvisation on the Muddy Waters classic, Rollin’ Stone takes electric blues back to the source and plants an almighty hook in an E minor pentatonic lick

Muddy Waters is widely revered as being one of the most important musical figures of all time and the “father of modern Chicago blues.” His great many recordings, spanning from 1941 to 1982, are among the most important and influential of all time.

His 1948 single for Chess Records, Rollin’ Stone, set the template for many of his hit records to follow. In the early ’60s, certain young Englishmen joined forces based on their love of Chess Records, blues and rock and roll to form a band, taking their name from this early Muddy Waters hit, dubbing themselves the Rolling Stones, doing their part to ignite the soon-to-come British Blues explosion.

By the end of the ’60s, guitarists such as Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Johnny Winter had used the influence of Waters to forge completely new, trailblazing sounds in modern music.

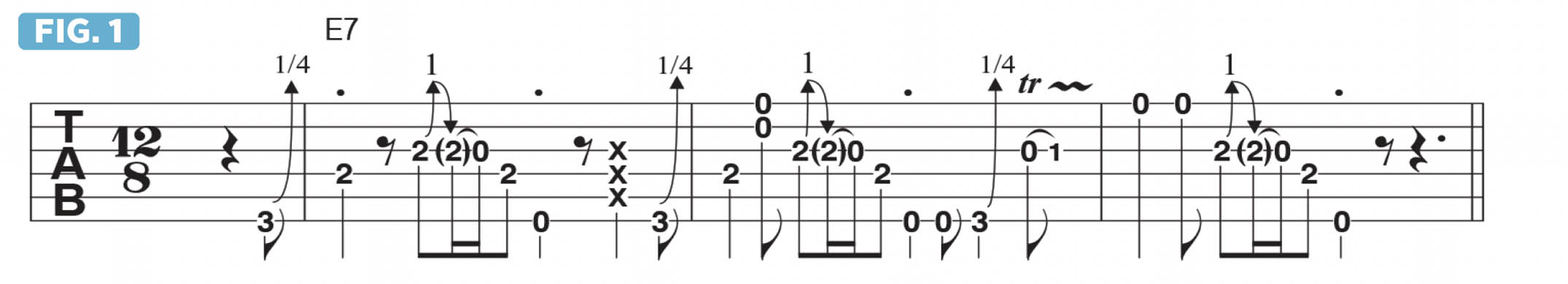

A great place to start exploring Muddy’s signature guitar style is this track, Rollin’ Stone. The song is built around a simple riff in E, based on the E minor pentatonic scale (E, G, A, B, D). As shown in Figure 1, the riff is played in 128 meter, with a pickup of a slightly bent low G note on the 6th string’s 3rd fret followed by E, on the 2nd fret of the 4th string.

On beat two of bar 1, an A note on the G string’s 2nd fret is bent up a whole step and released, followed by a pull-off to the open G string and a fretted E note. As shown in bars 2 and 3, this riff repeats with slight variations, as open strings and other rhythmic accents are added.

The bent-and-released A note serves as the “hook” in the lick, and Muddy would always place it on beat 2 as the song progresses. You’ll hear the very same thing happening in Jimi Hendrix’s classic song Voodoo Child (Slight Return), which was directly influenced by this Muddy Waters recording.

This type of slow 128 blues in the key of E is great for devising improvised ideas, as evidenced by the many great versions of Voodoo Child (Slight Return) recorded by both Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Muddy himself had a “part two” to Rollin’ Stone, which he called Still a Fool, and both Hendrix and Winter took the liberties to combine Rollin’ Stone and Still a Fool into a song that they both called “Catfish Blues.” Be sure to check out these incredible recordings!

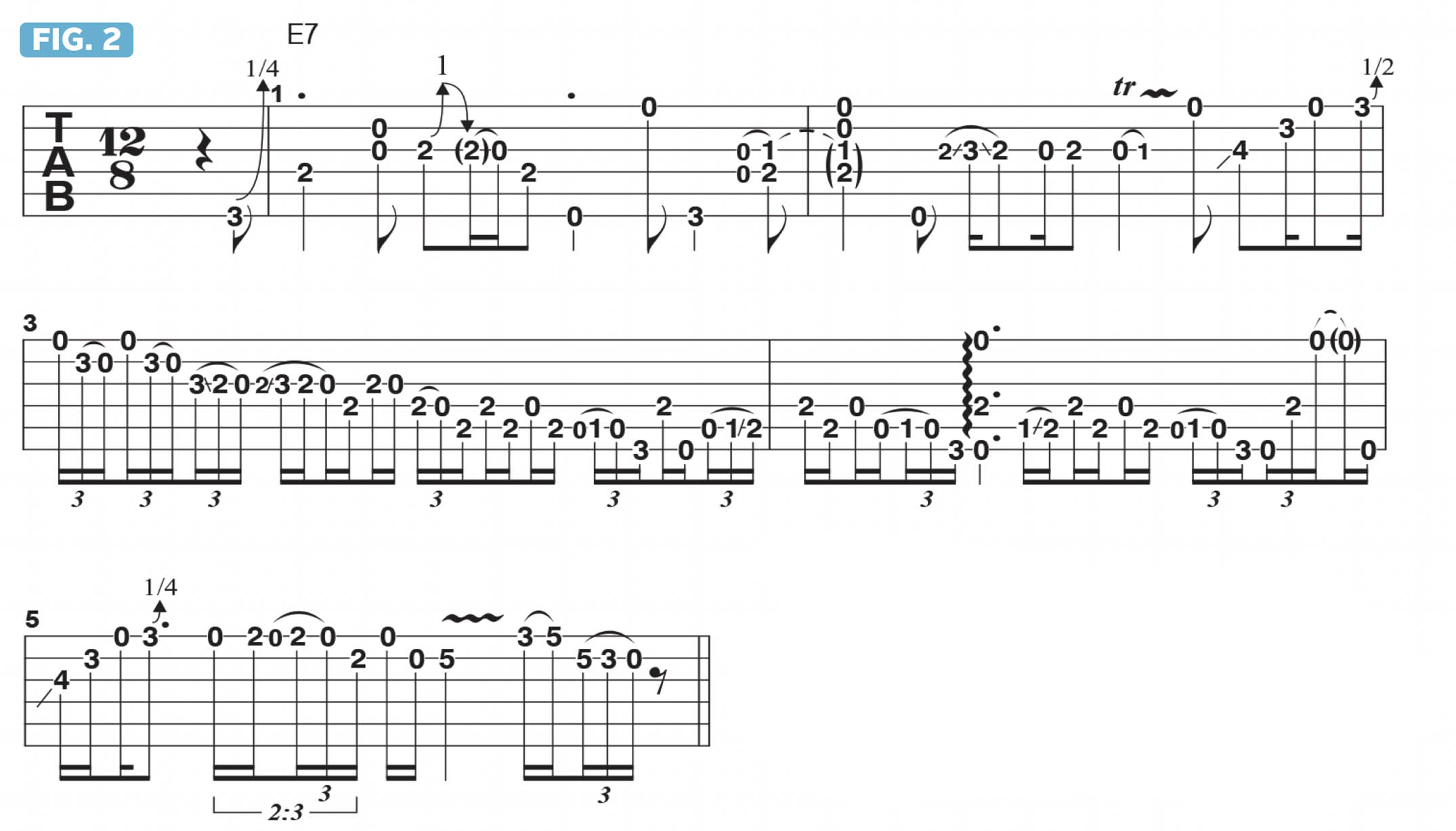

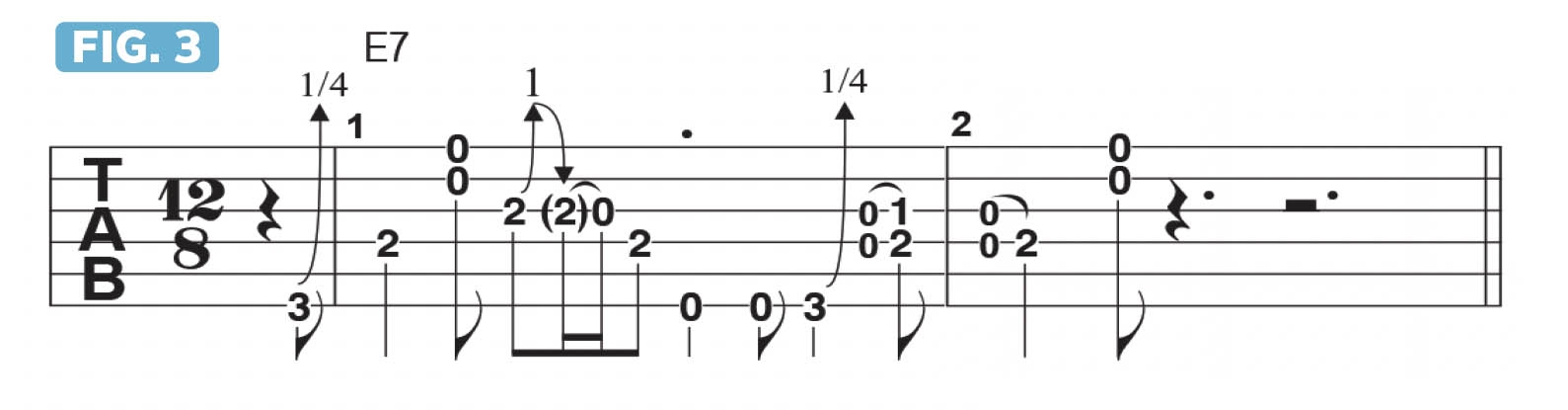

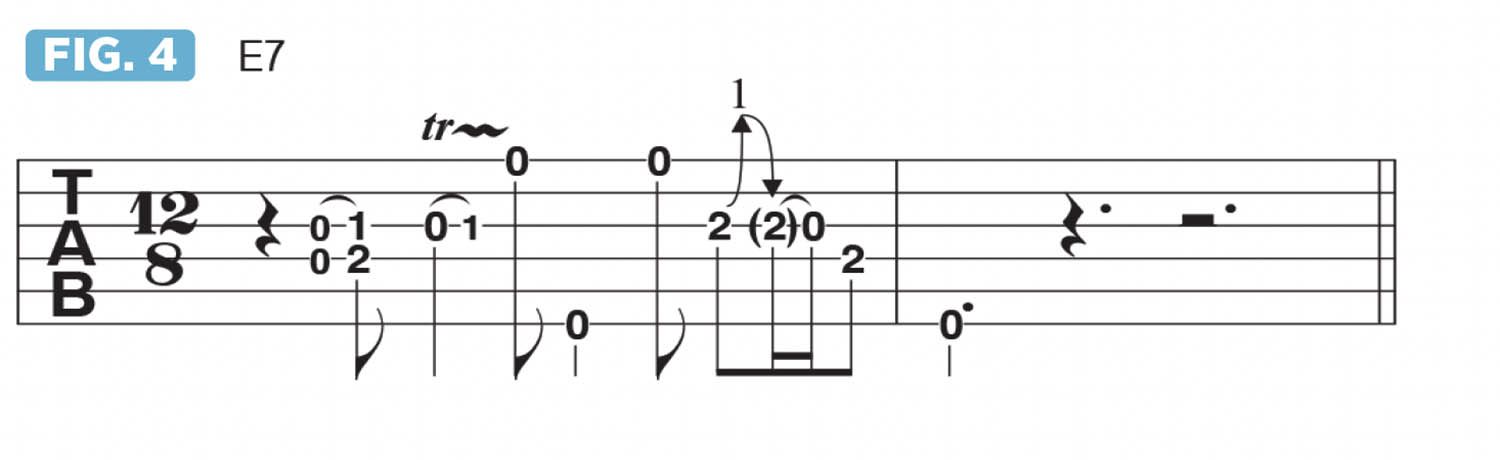

In Figure 2, I build off of the original lick by moving through different ideas based on the E blues scale (E, G, A, Bb, B, D). A simple twist used by Muddy, as well as Jimi, on songs like Machine Gun, is to hammer on E and G# together, as in Figures 3 and 4.

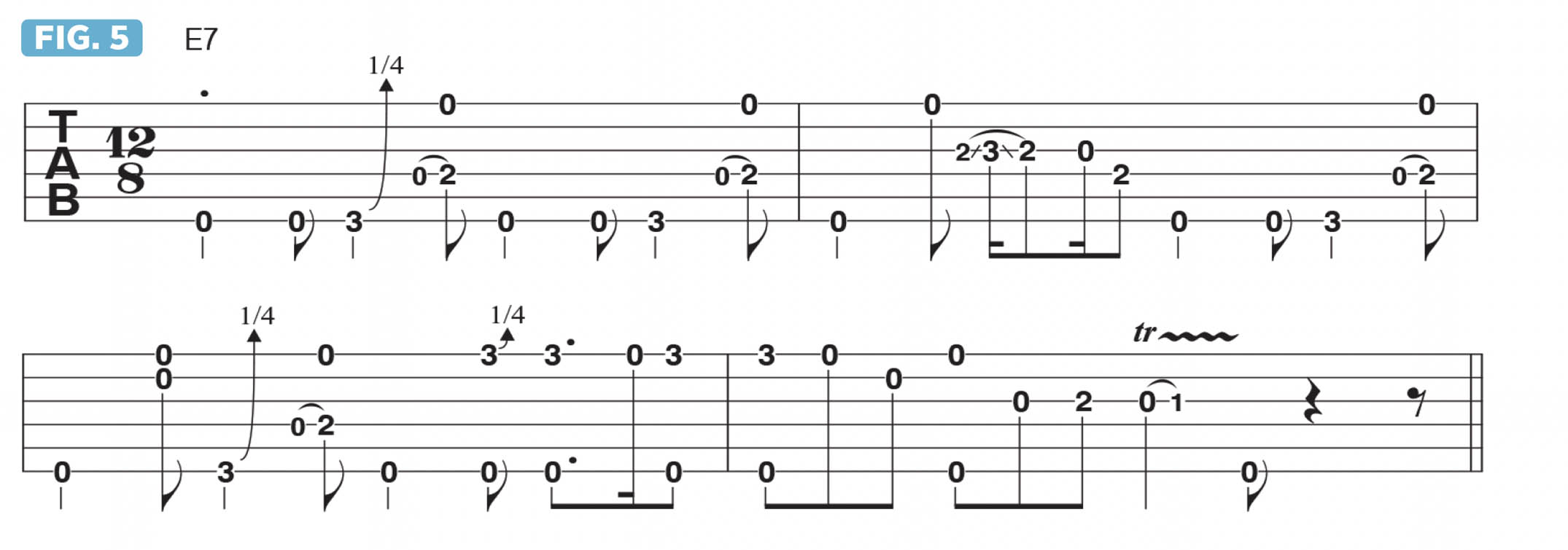

Before moving into more soloing approaches, let’s lay down a basic guitar accompaniment for the tune’s verse sections.

As shown in Figure 5, the phrase introduced in Figure 1 lays the foundation, with slight variations added that support the vocal melody.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.