How to play Motown rhythm guitar

R&B, soul, Motown, it all goes well with the blues – and with the following four examples, you can add a little invention to your rhythm game

Before we go any further, I want to define what I am calling ‘rhythm’ guitar. Many of the great blues artists such as BB King, Albert Collins and Albert King were soloists who didn’t really ‘do’ chords, but I wanted to have a play here with the guitar as a ‘featured instrument’ – not necessarily playing a solo or melody but not relegated to strumming inaudible block chords, either.

That said, the bass and drum backing provides very little harmonic detail, so it is also necessary that the guitar steps in here, while providing a bit of rhythmic and melodic variety. This sounds like a very tall order indeed, but if we talk through our options, hopefully you will see it is completely possible to develop a flexible approach that also allows for some spontaneity.

Another bonus is that the skills we sharpen here can be applied to any style or genre with a bit of imagination and a change of tone or pickup setting. I’ve gone with a soul/R&B/Motown vibe and played five short alternative takes over the same backing track.

These progress from almost entirely chords to quite a sparse single-note melody, with a mixture of approaches and chord voicings between those two extremes. I was imagining a producer asking me for different options (a fairly common scenario), including coming up with little ‘hooks’ in the form of embellishments or single-note lines. If you’re playing on an existing song, the vocal melody (or even the lyrics) can be a great source of inspiration for parts like these.

As you place your fingers on some of these chord inversions, you may also recognise fragments of pentatonic scale. This is all to the good – try to ‘file’ those realisations for future use. Hope you enjoy these examples and see you next time!

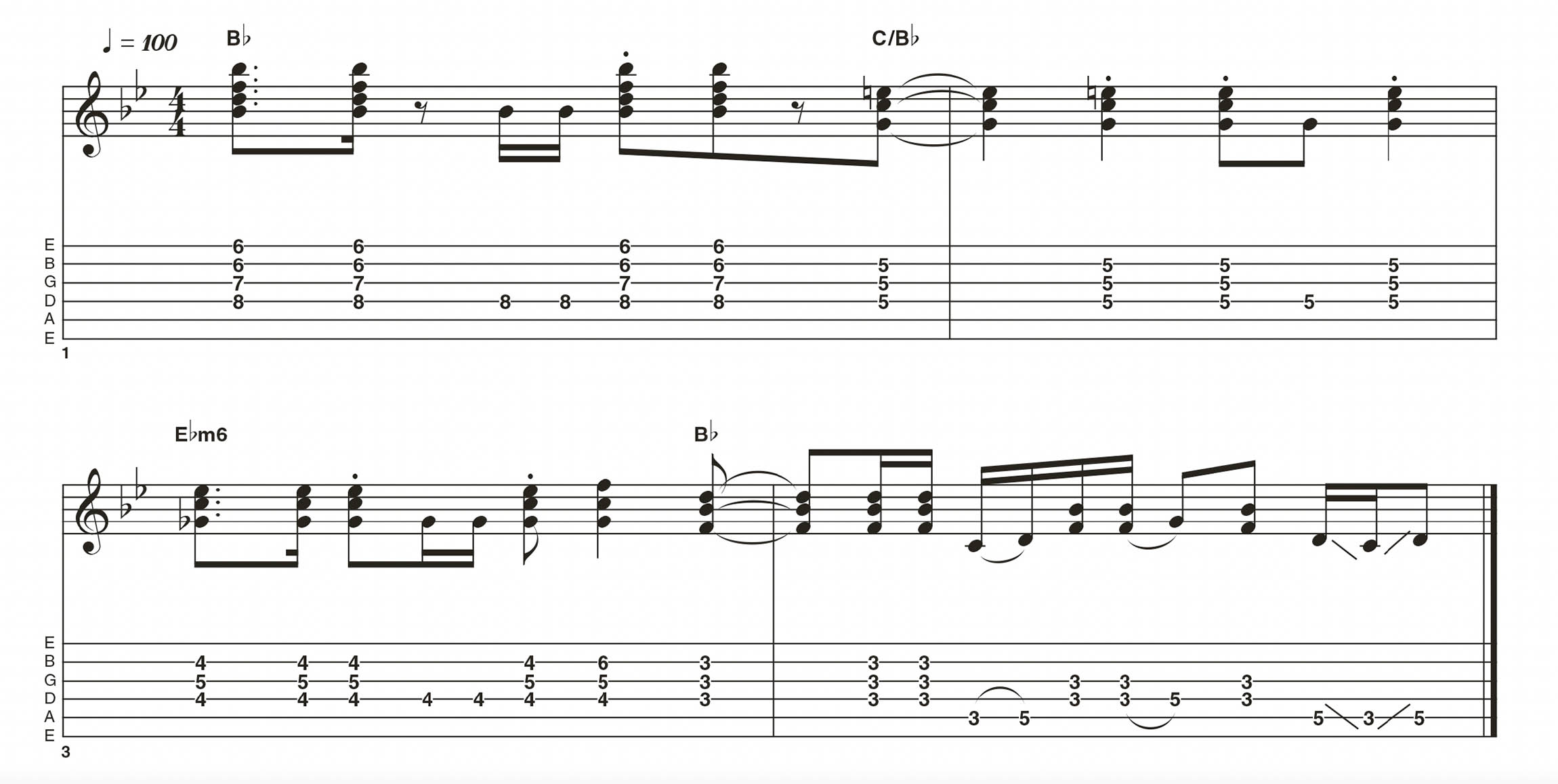

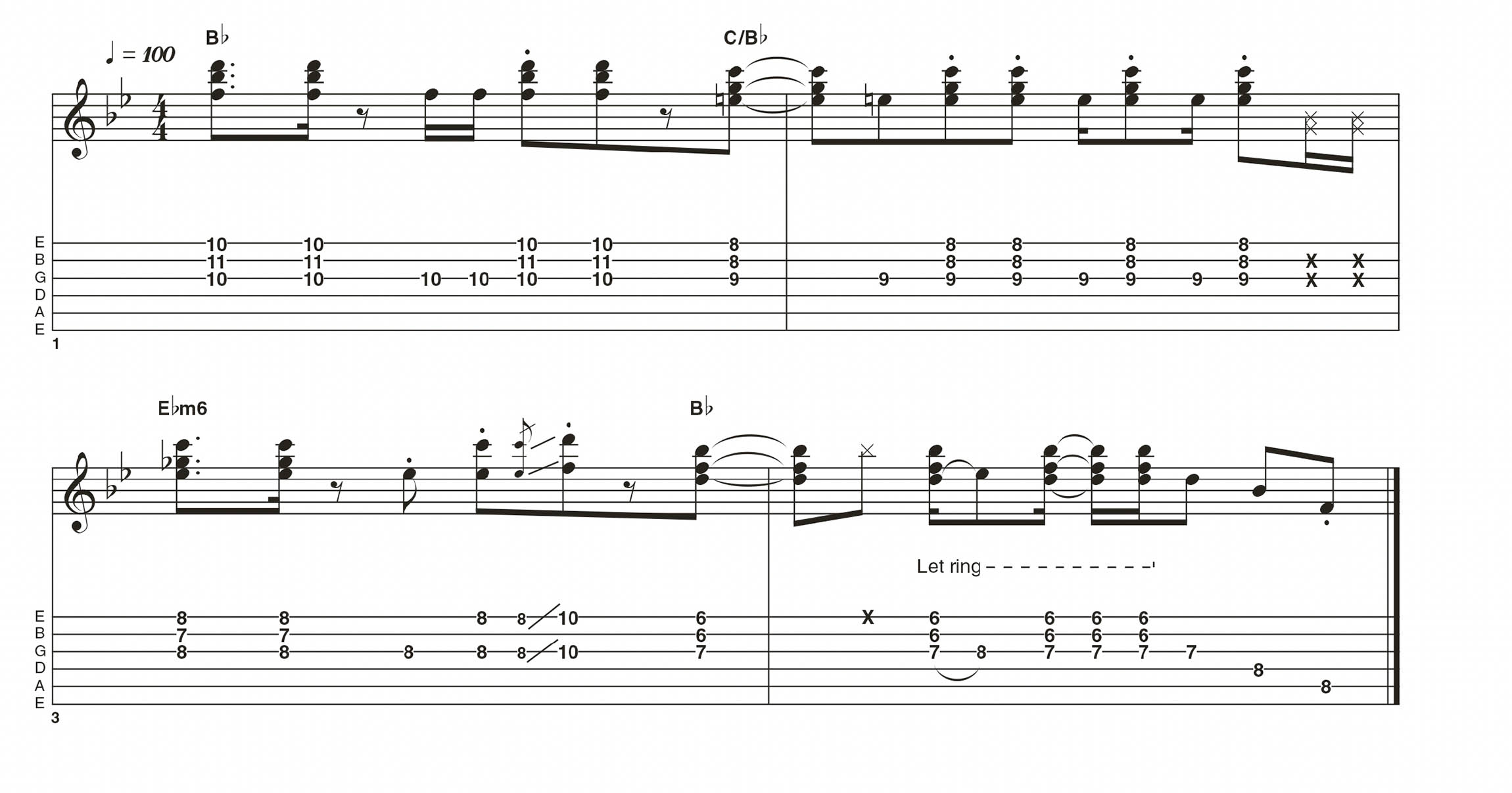

Example 1

This first example sets up the rhythmic and harmonic patterns that the other examples follow – albeit taking a few more ‘liberties’ as we go. The rhythmic feel is based mostly around a mixture of staccato and looser downstrokes.

However, you’ll see on the video that there are upstrokes in there, too, even if they don’t always connect with the strings. This helps keep any offset rhythms on track without feeling like you have to count each semiquaver to calculate whether an upstroke or downstroke would be best.

Example 2

Expanding on what I hinted at in the final bar of Example 1, this still outlines the harmony pretty clearly, but it allows a few doublestops to spice things up. Note the different inversions, which fall within the CAGED and pentatonic shapes.

If you’re working with a vocalist or soloist, be sure to choose your moments for these, for two reasons: you don’t want to intrude on their territory, and you want your embellishments to be heard.

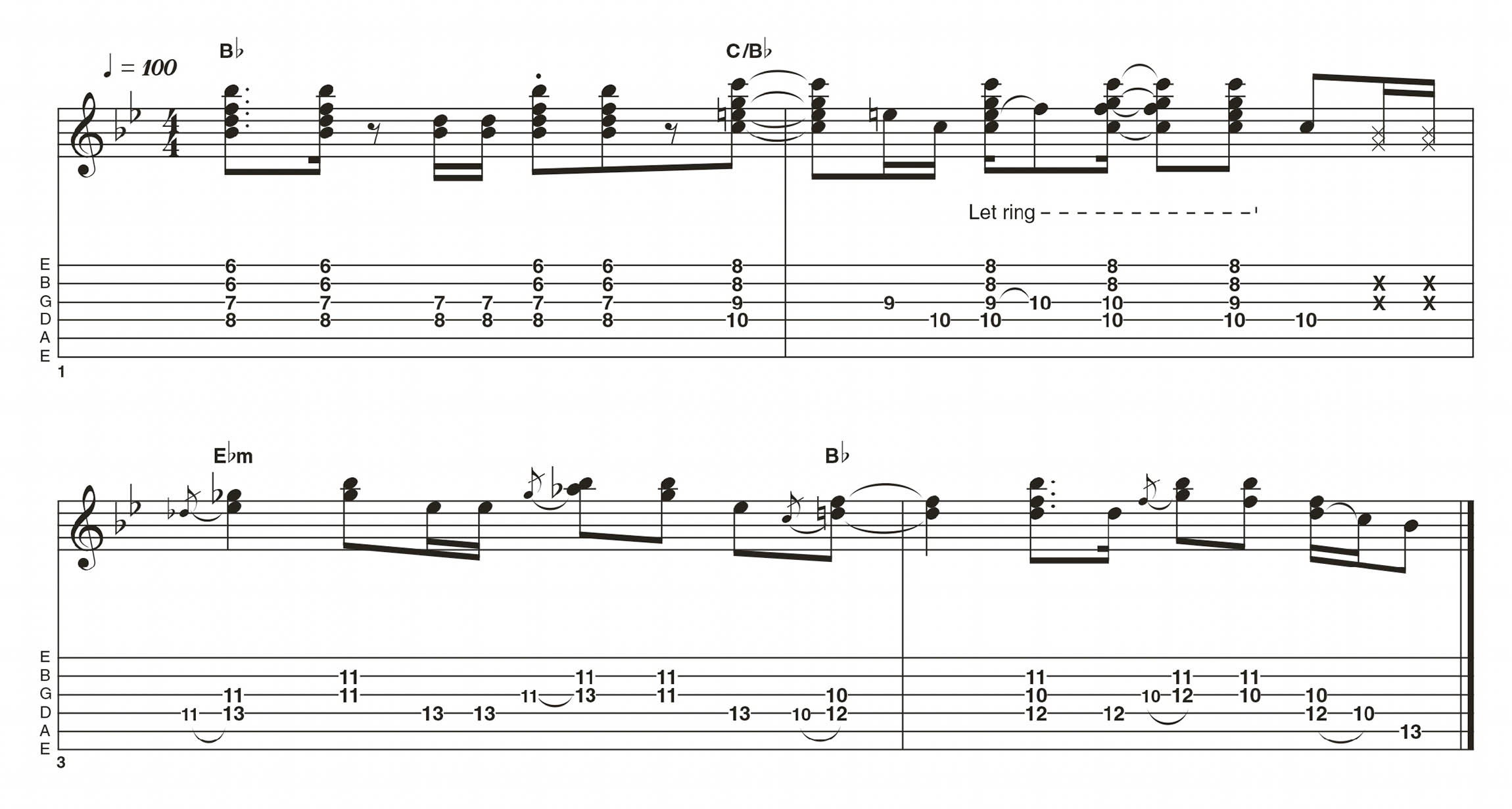

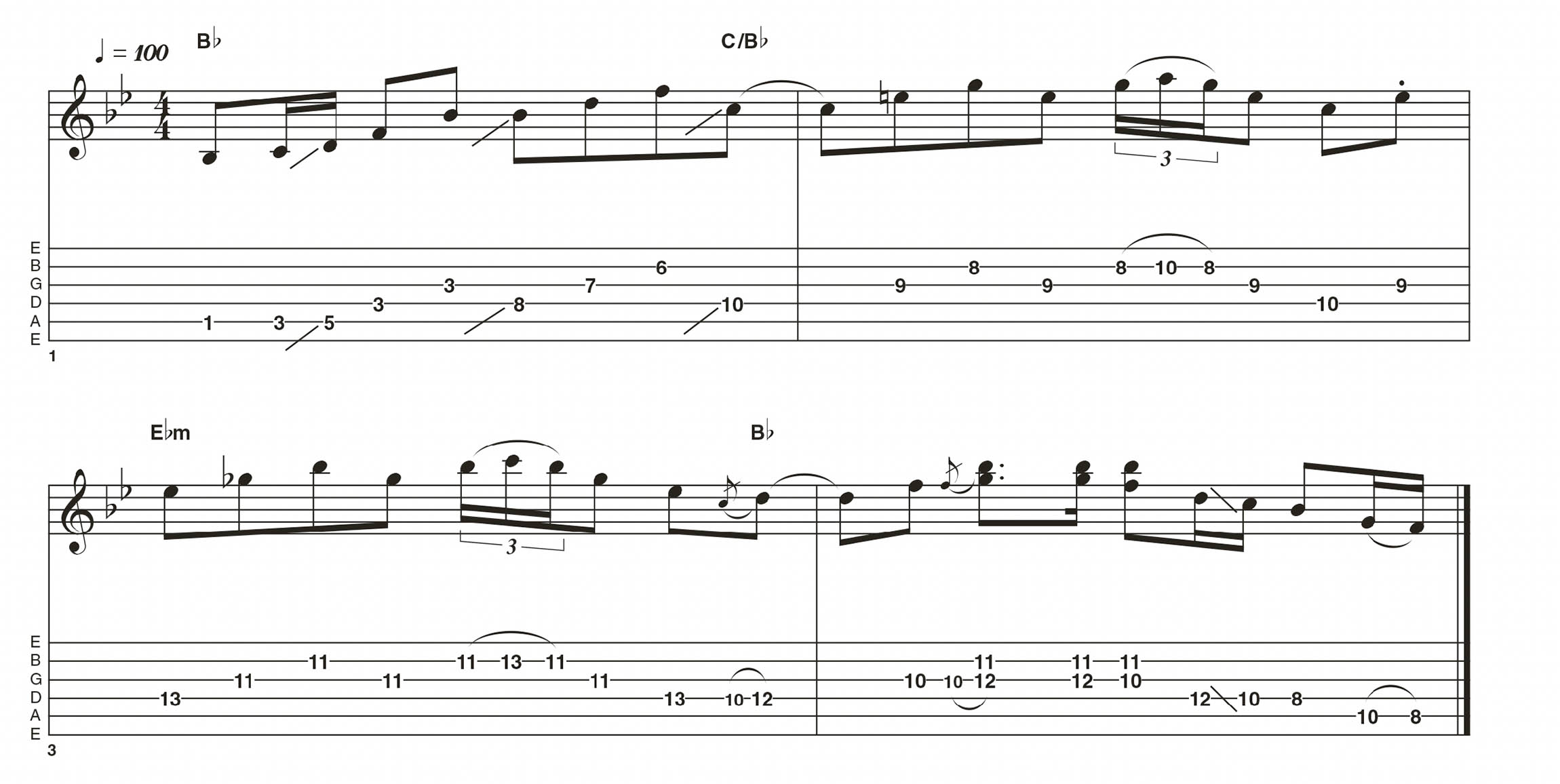

Example 3

Moving on up (pun intended) to a higher register, I’ve switched to three-note triads. This gives a little more focus to what would likely be quite a prominent part – and smaller chords are easier to move around! In this take, I’ve varied the rhythm a little, most noticeably in bar 2.

Notice how I’ve gone with the Little Wing school of thought for the Bb/sus4 movement in the final bar. Not so many embellishments here, but the nature of this part is pretty upfront anyway.

Example 4

A change to the bridge pickup here gives a different feel, which I thought suited this mixture of pentatonic melody and chord embellishment. After the initial melody, I’ve stayed within and arpeggiated some three-note versions of the chords.

Bars 3 and 4 feature a little hammer-on as a nod to the way Jimi Hendrix or Curtis Mayfield would embellish their rhythm parts, before the final bar returns to the pentatonic approach we started out with, only now we’re up around the 12th fret.

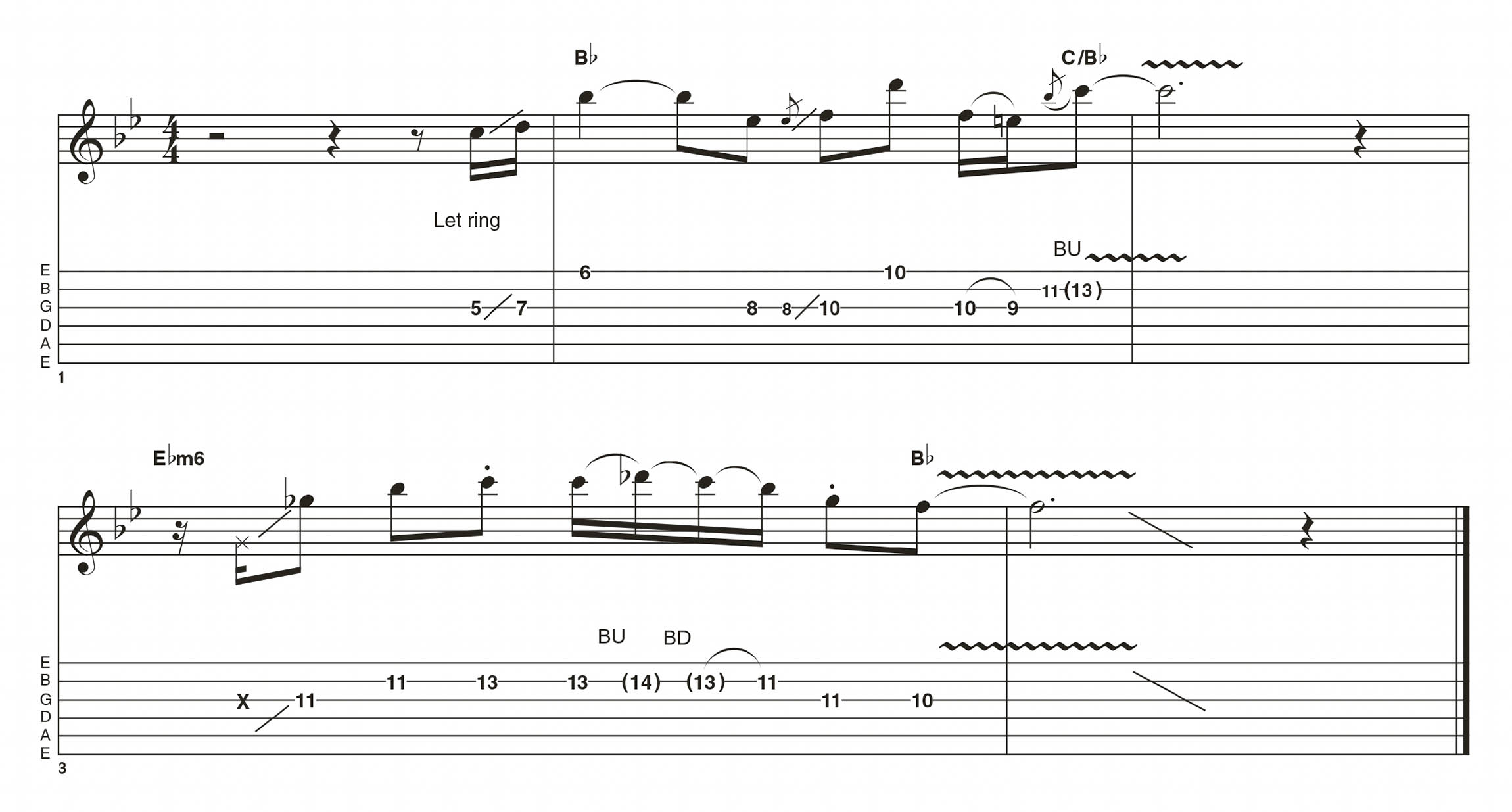

Example 5

More of a melody than a solo or rhythm part, this example uses some 6ths (in the way that Steve Cropper might) to outline the harmony, while allowing the flexibility to switch to a single-note approach without feeling the chords have abruptly dropped out.

A line such as this would benefit from a chord accompaniment from a ‘production’ point of view, but note that it does actually spell out the harmony far more than a ‘standard’ pentatonic solo might.

Hear it here

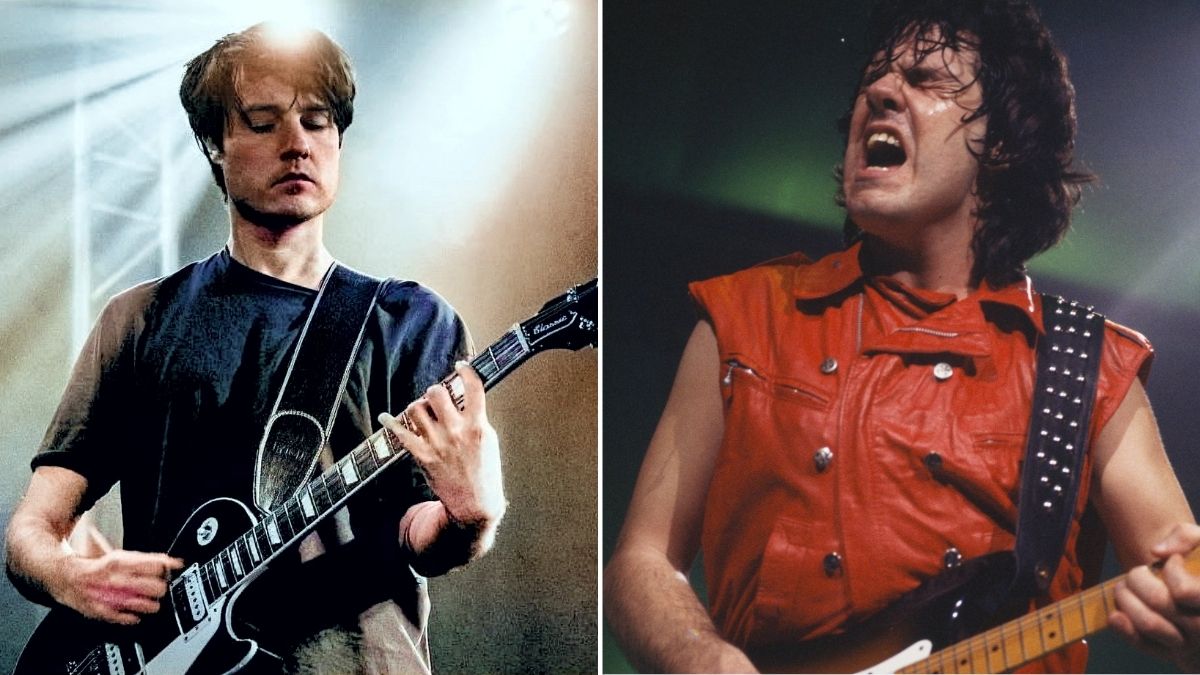

Robert White – Motown Anthems

Robert was an integral part of the Funk Brothers, along with guitarists Eddie Willis and Joe Messina. Their ‘one-for-all’ teamwork resulted in interlocking, complementary parts on many classics, but I’ve singled out Robert for his pentatonic intro on The Temptations’ My Girl, the Morse code-style octaves on The Supremes’ You Keep Me Hangin’ On, and the strummed chords that deliver the foundation for Stevie Wonder’s My Cherie Amour.

Curtis Mayfield – Roots

You’ll need to listen closely for Curtis’s inventive rhythm guitar in the mix among the orchestrations, but this is well worth the effort. Check out the way he weaves in and out of the rhythm on the anthem Get Down.

Other highlights include his embellished arpeggios on Keep On Keeping On, and Now You’re Gone is a great example of Funk Brothers-style complementary parts with staccato chord chops, wah textures and bluesy fills.

Tony Joe White – Tony Joe White

Funk and blues collide here with a neat side order of tasteful wah and Motown-style arrangements. Check out They Caught The Devil And Put Him In Jail In Eudora, Arkansas (worth it for the title alone!).

My Kind Of Woman brings some pentatonic riffs it would be easy to imagine Jimi Hendrix coming up with, and, finally, be sure to listen to A Night In The Life Of A Swamp Fox, with its mixture of chords, melodic figures and bluesy licks.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)