Harness Joni Mitchell's acoustic imagination with this lesson on dulcimers, altered tunings and cluster chords

A deep dive into the singer-songwriter's aptitude for experimental tunings, and how you can incorporate them into your own compositions

For Joni Mitchell, songwriting is as much about crafting a tuning as it is about choosing the chords, melodies, or lyrics. Her creative process is a fluid, intuitive blend of many musical elements, drawing on ideas spanning blues and banjo techniques to jazz harmony and indigenous folk songs.

By her own estimation, she has used more than 50 different tunings over the years – or 80-plus if you count capo'd variants.

Her expansive, imaginative approach to tuning has roots in her earliest creative experiences. Born to a military father and a school teacher mother in small-town Canada, she was drawn to painting and poetry before music as a child, obsessing over the former in particular.

But despite an irrepressibly inquisitive mindset, Joni struggled to find inspiration in her school curriculum – save for a bond with one encouraging teacher. She describes this nameless early influence as “a great disciplinarian in his own punk style... more of a social worker or a renegade priest... [he] extracted the individuality of his pupils, creating monsters who were almost ungovernable within the rigidity of that system. We nearly drove our next year's teacher nuts.”

Similarly, the rigid strictures of classical piano lessons did not enthuse her: “I wasn't into music....I wanted to do what I do now, which is to lay my hand on it and to memorize what comes off of it and to create with it. But my music teacher told me I played by ear, which was a sin, you know”. She asked for a guitar, but her mother – reportedly wary of its “hillbilly associations” – got her a ukulele instead.

When she did eventually get an acoustic, she taught herself from a book by banjoist Pete Seeger, also learning old blues numbers – notably the ‘Cotten picking’ alternating bass style of Elizabeth Cotten’s Freight Train.

Even at this early stage, she was used to switching between different instruments and string layouts (four-string ukulele, five-string banjo ideas on a six-string guitar, etc). Additionally, a serious polio episode had weakened her hands, probably making the physical ease of slacker tunings more attractive.

As a young, unknown performer she was entranced by seeing guitarist Eric Andersen play in a Detroit nightclub. Andersen, who had studied the slide tunings of Muddy Waters and Mississippi Fred McDowell, recounts that Joni “hated playing guitar in standard tuning... boring, missing many musical regions she had in mind”.

“I was playing in E, D, and G tunings. Afterwards we went to her lovely home. She was curious about these tunings, so I showed her...”. They would go on to record and perform together, and remain close friends today (Joni is godmother to Eric’s daughter).

The E, D, G tunings mentioned by McDowell are [E-B-E-G♯-B-E], [D-A-D-F♯-A-D], and [D-G-D-G-B-D]. Joni used them as fuel for decades’ worth of multidirectional exploration – though she went far further in before long, these are the starting points in many ways. So here they are, tuned with a little bluesy roughness and imperfection:

Below, we get stuck into a few of Joni’s most distinctive tunings and ideas. In keeping with the initial foundations of her own approach, we’ll be treating them more like ‘color palettes’, without so much explicit focus on harmonic or intervallic analysis.

In her words, “I was a bad English student because I was good in composition, but I wasn't good in the dissection...I didn't like to break it down and analyze it in that manner.” This, of course, is absolutely no barrier to harmonic or expressive sophistication.

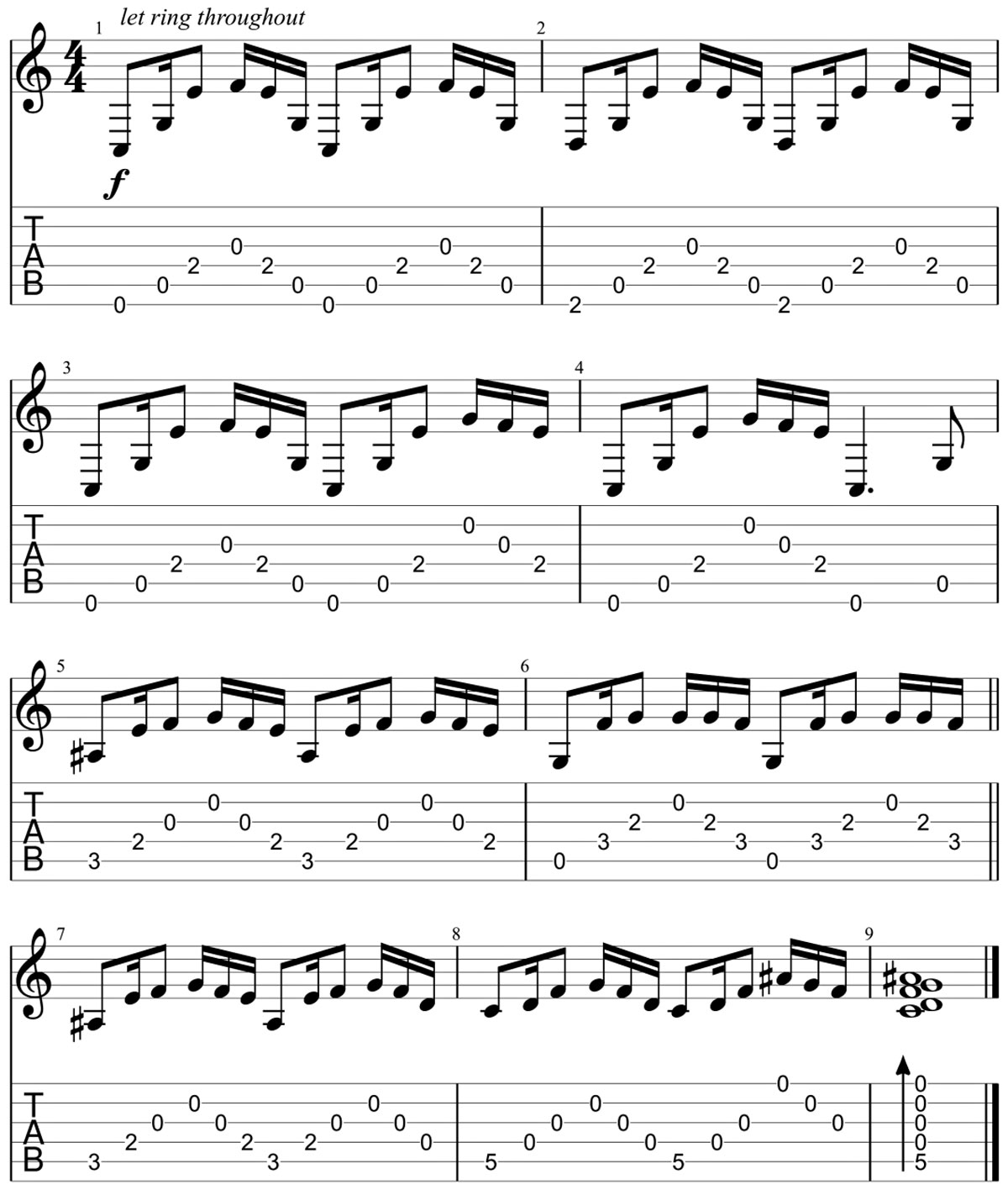

Exercise 1. Hejira-style tuning (C-G-D-F-G-Bb)

Joni’s fascination with blending folksy melodies and nuanced jazz harmony reached its most seamless heights on her collaborations with Jaco Pastorius - an extraordinary musician, often described as ‘Hendrix of the fretless bass’. She describes what led to their partnership:

“I had tried all along to add other musicians...Nearly every bass player that I tried did the same thing. They would put up a dark picket fence through my music, and I thought, why does it have to go ploddy ploddy ploddy? Finally one guy said to me, ‘Joni, you better play with jazz musicians.’”

Jaco overdubbed several sublime bass parts for Joni’s 1976 album Hejira – an Arabic term she loosely transliterated from a dictionary, meaning ‘rupture’ or ‘break with the past’, and signifying the migration of Muhammad to Medina (in Joni’s words, she was searching for a term which meant ‘running away with honor’, a recurring lyrical theme throughout).

The album’s title track presents a perfect balance of their distinctive sonorities. For Joni, it was “probably the toughest tune on the album to write”, with lyrics tackling a recent breakup with jazz-rock drummer John Guerin (...although three tracks later, Blue Motel Room muses on whether the relationship could be rekindled).

It was also one of Jaco’s first experiments with overdubbing, something he would later famously apply to the live setting with a loop pedal. On Hejira he recorded four separate layers of bass, combined sparingly with Joni’s two not-quite-identical guitar parts:

In the exercise below, we approximate Joni’s tuning for Hejira. It is generally considered to be C-G-D-F-G-C, which here we will tweak to C-G-D-F-G-Bb. If, like the track, we take our open 6th string as the root, we can see the arrangement as follows - this is about as much ‘theory’ as we’ll get into in the whole lesson.

(n.b. once you’ve tuned the 6th string, the ‘fretmatches’ are the frets you press to tune the next one over, i.e. instead of ‘5-5-5-4-5-x’ for standard tuning):

- Notes: C-G-D-F-G-Bb

- Intervals: 1-5-2-4-5-b7

- Fretmatches: 7-7-3-2-3-x

The study below explores this tuning with some of Hejira’s characteristic fingerpicking patterns - although it works fine with a pick too if you can handle the string-skips. Hear how the open strings allow for floating, harp-like resonations, which hang in the air and recolor all the notes around them, being ‘recharged’ back to full volume with each cycle of the fingerpicking sequence:

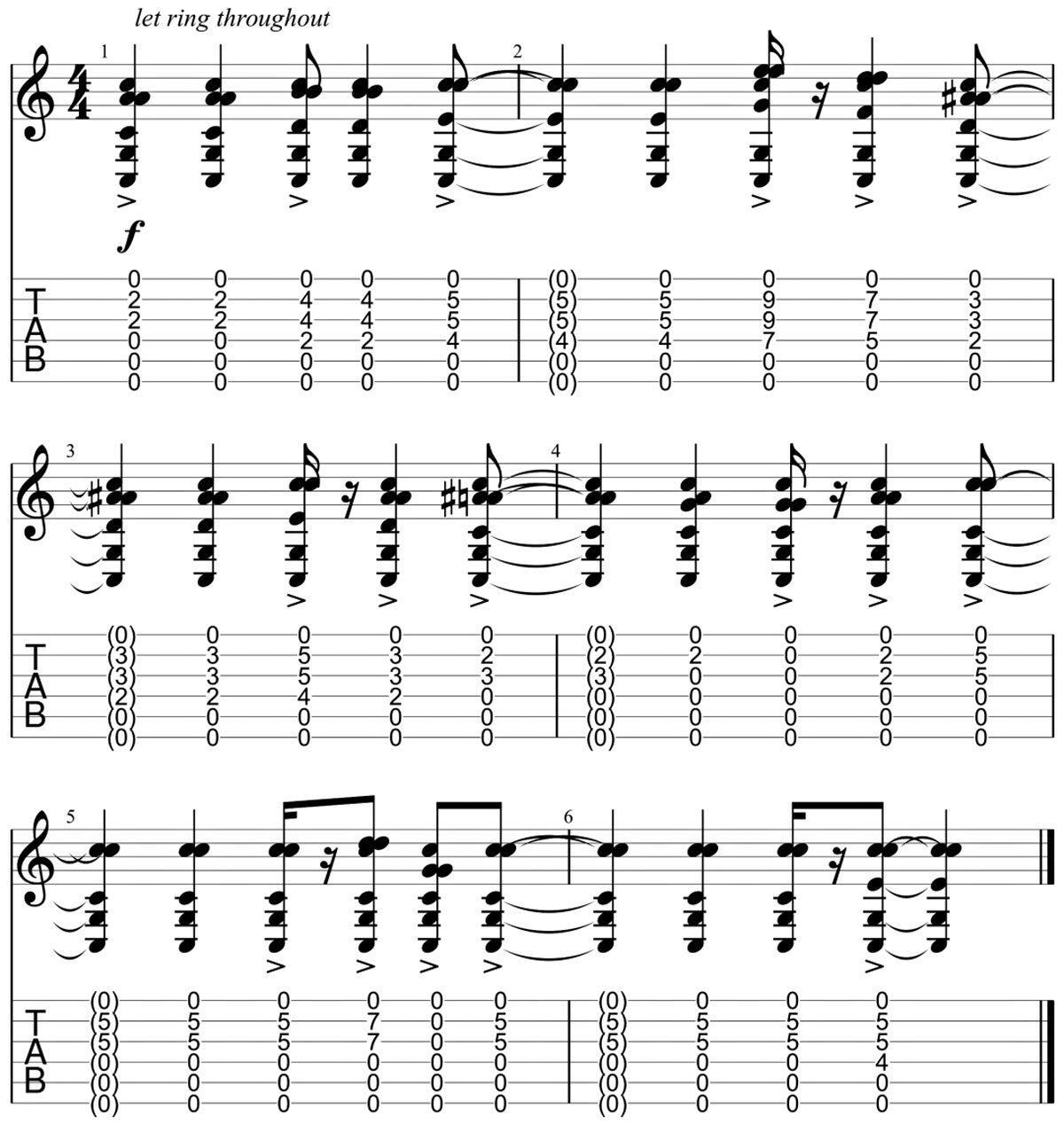

Exercise 2. Appalachian dulcimer tuning (C-G-C-G-G-C)

Joni didn’t just play guitar and piano. She also recorded and performed on the Appalachian dulcimer, a 3-to-5-stringed folk instrument placed flat on the lap. Joellen Lapidus, who first introduced her to the dulcimer, tells the story:

“One day I found out there was going to be the Big Sur Folk Festival and I thought to myself, ‘I'll make a dulcimer and call it the Festival Model. And I'll sell it to either Joni Mitchell or The Incredible String Band.’ They were both my idols at the time....I told all my friends and they said yeah, yeah, yeah. So, anyway, I went out into woods, looking for inspiration, and there were these beautiful red, wild columbines. And I just thought, ‘That's it.’”

“I brought it to the festival...and I saw Joni walking down the path, and I just put the dulcimer right in front of her... She said, ‘Oh, what is that instrument?’ And I said, ‘It's a mountain dulcimer.’ She said, ‘Well, what does it sound like?’ So I played for her and I told her, I said, ‘You know, this is something that you could really get into, because it's all open tunings..."

Joni immediately saw what Joellen meant, and went on to play the dulcimer some of her best-known songs, including Carey, A Case of You, All I Want, and California. Her approach to learning it gives us core insights into her guitaristic thinking, too – she bought it without really knowing anything about how it was supposed to be played, so had to work it out herself based on her own intuitions and musical desires.

She explained the beginnings of this journey in a 1996 interview: “The only instrument I had ever held against my knee was a bongo drum...so when I started to play the dulcimer I beat it. I just slapped it with my hands...” She would retain this percussive essence, supplementing it with other non-traditional ideas including characteristic palm-muted strums.

In fact, the only dulcimer instruction she ever received in these early days was when Joellen briefly showed her a few strumming techniques around the time of purchase. And Joellen, a self-taught player, had in turn adapted her style from her main skill as a folk guitarist.

But these two ‘outsiders’ are now hailed as pioneers by the global dulcimer community - Joni for doing more than anyone before or since to popularize their instrument in the public eye, and Joellen for how she “sings and plays the dulcimer with complex rhythms, while incorporating a variety of musical genres from folk to jazz to Arabic...”

In this exercise we go ‘back to source’, imitating Joni’s guitar-derived dulcimer style with some open-tuned, folksy chords on the actual guitar. In keeping with her general musical approach, she turned to a variety of different dulcimer tunings over the years, and even rearranged the strings for a time, putting the bass in the middle for a less ‘directional’ strumming resonance.

Here, we approximate the common ‘perfect 5th’ dulcimer arrangement she used on Carey (DDAA), tuning to a wide, pure-toned setup of C-G-C-G-G-C from low to high:

- Notes: C-G-C-G-G-C

- Intervals: 1-5-1-5-5-1

- Fretmatches: 7-5-7-0-5-x

Your strings will probably sound buzzy and slack. To some degree this is part of the dulcimer tone we want, although shorter-necked guitars and thinner string sets may struggle a bit when tuned very low.

We also have to contend with ‘inharmonicity’: essentially, the fact that the physical vibration of a string is essentially a small, ever-shifting set of ‘bends’, meaning that – in literal terms – all strings always ring a little sharp (as they do with any type of bend).

In standard tuning we don’t really need to worry about this very much, as the effect is minuscule, but it comes into play with low, loose tunings, especially if we pluck forcefully. Hear inharmonicity in action on my down-tuned 6th string:

So in the exercise below, be careful not to pluck too hard, or push down on the fretboard with undue force. In the exercise we imitate the dulcimer’s limited range of strings by only fretting on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th strings, just using the others to add color and textural depth:

Insights from Joni’s paintings

Joni famously described herself as a “painter derailed by circumstance”. As detailed above, her first creative passion was visual art rather than music - in her teens she studied with painter and interior designer Henry Bonli (he found her “an argumentative pupil”), and later enrolled at the Alberta College of Art before dropping out aged 20. She continued painting throughout her career, designing many of her own album covers and receiving acclaim for gallery exhibitions.

All facets of creativity are inextricably interconnected – especially in Joni’s case. Many of her tracks have corresponding paintings, made in tandem, and in several interviews she refers to how she visualizes sound itself, seeing it as “colors and shapes”.

She would often draw or paint to settle nerves and pass the time before concerts, and describes sometimes having to be “dragged away” from the activity when it was time to get onstage.

It’s useful to think of Joni’s approach to tuning in similar terms. For example, you can just pick up a guitar and play it, but you can’t start painting without deliberately picking out which colors you want to put on the brush.

In essence, Joni treats the tuning process like this ‘color selection’ step – each one brings its own tones, shades, and densities, meaning she can draw on a fuller overall spectrum in her work. To her, confining yourself to standard tuning is like ignoring all the other paint pots.

So to get closer to her music, have a look at some of her intriguing visual art too - for example her vivid self-portraits, and Morning Glory on the Vine, a book of watercolors originally produced for friends which includes a striking portrait of close friend Neil Young.

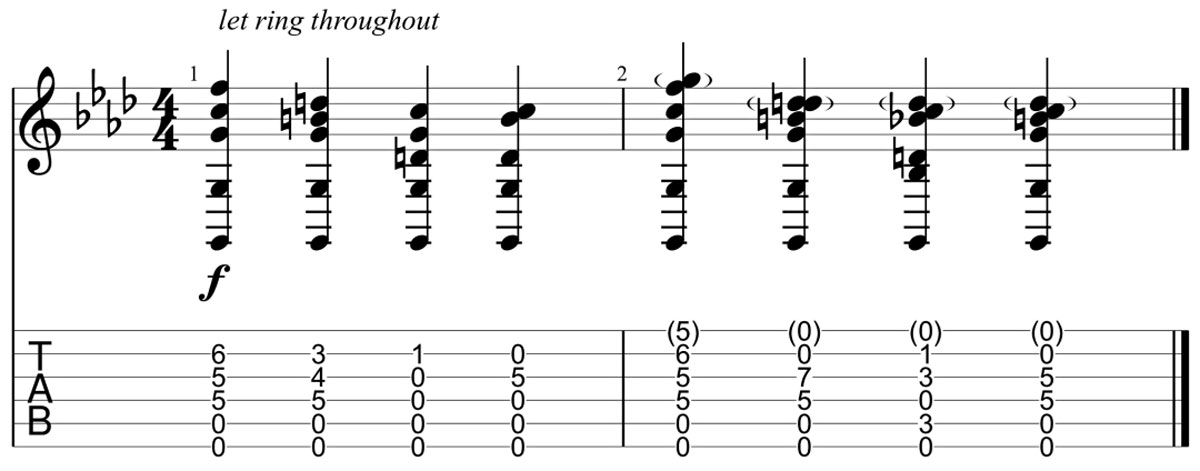

Exercise 3. This Flight Tonight-style tuning (G-G-D-G-B-D)

For the final exercise we turn to one of the few non-piano songs from Blue, one of her best-known albums. As noted by guitarist Howard Wright, This Flight Tonight takes a tuning of Ab-Ab-Eb-Ab-C-Eb, essentially the blues open G we heard at the start (D-G-D-G-B-D) moved upwards a half-step, with the 6th string lowered to a whole octave below the 5th for some ‘slack thwack’. Here’s how we can mirror this idea while minimizing retuning:

- Notes: G-G-D-G-B-D

- Intervals: 1-1-5-1-3-5

- Fretmatches: 12-7-5-4-3-x

Joni was consistently frustrated by the exacting nature of her early art lessons. In this spirit, I’m just going to give you a brief chord sequence for this one, which aims to capture the character of her ambiguous, cycling resolutions (as she christened them, “Joni’s weird chords”). See what you can draw with these starting colors:

Round-up

Of course, this lesson is only a small window into what is now a long lifetime of tuning explorations. Joni’s arrangements gradually moved lower down as the pitch of her voice dropped with age, and she contended with the added complexities of touring by simplifying her system, bringing along five separate Ibanez jazz guitars, each strung differently to allow for a clear tone at different tensions.

Ever keen to experiment, she played through a Roland VG-8 synth for a time, which allowed her to digitally alter the guitar’s tuning without actually retuning the strings themselves.

If you want to use Joni’s other tunings as starting points, see the heroic, fan-compiled List of guitar transcriptions sorted by tuning pattern on her website, along with a superb Tips for guitarists playing Joni songs page, covering such things as string gauges, fingerpicking techniques, and her mildly microtonal, James Taylor-style ‘stretched tuning’. Her legacy, deservingly, is in little danger of being forgotten by today’s guitarists.

The purpose of this lesson isn’t really to teach specific tunings. It’s more to remind us that we can take a ‘step back’ in our creative process, making deliberate choices about the natural colors of our tuning patterns as well as about the chords and melodies we set to them.

So for each of the exercises above, explore how you can recolor things by further altering the strings. Before long, you’ll have stumbled into some entrancing sonic spaces, that you wouldn’t otherwise have been able to dream up. And you’ll never run out of new tunings to explore...

Further learning

See more lessons on the Raga Junglism ‘World of Tuning’ - everything you didn’t realise you wanted to know about guitar tuning, from musical manuscripts from ancient China through to modern scientific insights into string vibration and the cognition of sound. Give me feedback too!

Read the curious tales of Joni’s guitars: “The first professional instrument she owned was acquired back in 1966, when she received a 1956 Martin D-28 from a Marine captain. The captain was in Vietnam when his tent was hit with shrapnel, injuring him. The captain had two guitars inside his tent at the time.

Joni claimed this Martin to be her best guitar ever. She wondered if the explosion did something to the modules in the wood, since the guitars sound was incredible.”

Hear from Joni herself in a rare, revealing NPR interview (Joni Mitchell At 75: Trouble Is Still Her Muse): “Her music has consistently made her vulnerability clear. And it is not the pretty kind. In another excerpt from an interview played at the concert, Mitchell complained of ‘being stereotyped as a magic princess ... you know, the sort of 'twinkle, twinkle, little star' kind of attitude’. Vulnerability, in Mitchell's songs, is often dissembling...”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.

“There are so many sounds to be discovered when you get away from using a pick”: Jared James Nichols shows you how to add “snap, crackle and pop” to your playing with banjo rolls and string snaps

Don't let chord inversions bamboozle you. It's simply the case of shuffling the notes around

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)