How using the augmented chord in a minor drop progression can change your songs

Paul McCartney, David Gilmour, George Harrison, Tom Petty and many more have done this in their music, so why shouldn't you?

Continuing our exploration of the augmented chord, which, as you recall, is a major triad with a raised, or sharped, fifth - 1, 3, #5 - I’d like to revisit a topic that we covered way back in the February 2018 installment of String Theory, which is how songwriters have employed this painfully sweet entity as a passing chord within what many musicians refer to as the minor drop progression.

As a quick review, the minor drop begins on a minor chord, or triad, then has the root note descending chromatically, in half steps, first to the major seven, then to the minor, or flat, seven (b7), then the major six, while the initial minor chord’s third and fifth remain static, or stay the same, serving as common tones throughout the sequence. This results in a progression that goes minor, minor major-seven, minor seven, minor six. Or, expressed as chord symbols, m - m(maj7) - m7 - m6.

In this scenario, the drop occurs within the chord voicing while the bass stays planted, or pedals, on the starting root note. Well known examples of this move can be found in the intro and verses to Tom Petty’s Into the Great Wide Open, the bridge to Veronica by Elvis Costello and the verse to This Masquerade by Leon Russell, covered beautifully by George Benson.

Sometimes, however, a composer decides to remove the starting root note after the first minor chord and put the chromatic drop in the bassline itself, so that only the third and fifth of the initial chord remain as common tones after the first change. This makes the second chord an augmented triad, rooted a half step below the minor chord that precedes it, which creates a slightly different sound that, without the abrasive clash between the root and major seventh that occurs in a m(maj7) chord, is less dissonant and therefore easier on the ears.

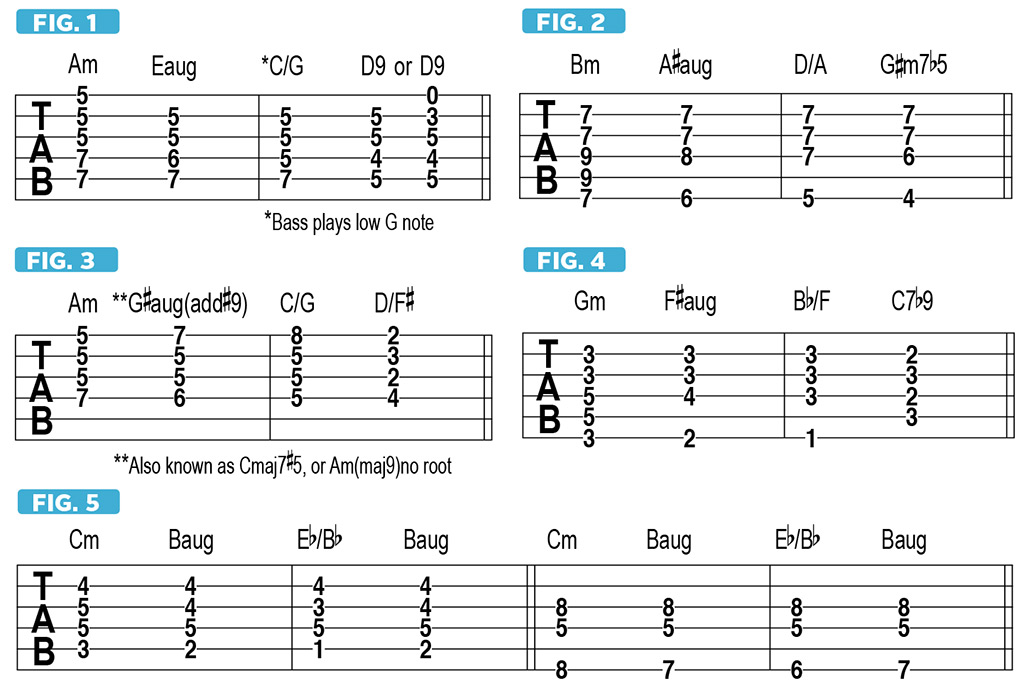

Probably one of the most recognizable and illustrative examples of this progression can be found near the end of each verse in George Harrison’s classic Beatles song Something, where the changes, played by organ and strings, go Am - G#aug - C/G - D9, similar to FIGURE 1. Interestingly, on the G#aug chord, bassist Paul McCartney goes up to a high E note, creating an inversion. (Remember, an augmented triad has three symmetrical inversions, so G#aug, Eaug and Caug are essentially the same chord.)

McCartney himself previously used a similar drop in the earlier Beatles song Got to Get You Into My Life, which is in the key of G, in this case starting it at 0:21, on the iii (three minor) chord, Bm. The part was arranged for horns, but FIGURE 2 translates the basic harmonic structure to the fretboard.

Getting back to the key of A minor, the iconic intro to Led Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven features a similar progression, but with a bittersweet twist, as guitarist Jimmy Page adds a high B note to the second chord in the progression, G#aug, making it G#aug(add#9), or Cmaj7#5 (C E G# B), although I think most people hear that in context as a rootless Am(maj9) chord (A C E G# B), à la the second chord in the famous jazz ballad My Funny Valentine, which does have the root present in the bass. Also noteworthy in Stairway is the contrary motion between the outer voices, similar to FIGURE 3.

Another classic example of this kind of application of an augmented chord can be found in Part IV of Shine on, You Crazy Diamond (Parts I-V), by Pink Floyd, specifically at 10:50, during the vocal bridge, or chorus, here in the key of G minor. FIGURE 4 outlines the basic underlying chord movement. Interestingly, the fourth chord in the progression, C7, has a flatted ninth (b9) added on top, which further accentuates the harmonic tension and dramatic impact of the phrase.

You Should be Dancing by the Bee Gees, which is also in the key of G minor, features a similar bass drop - in this case starting off the iv (four minor) chord, Cm, first heard at 0:30. Here, the changes go Cm - Baug - Bb/Eb - Baug, with the root motion reversing direction after the third chord and backtracking. FIGURE 5 offers two sets of guitar voicings for these changes.

Senior Music Editor 'Downtown' Jimmy Brown is an experienced, working musician, performer and private teacher in the greater NYC area whose professional mission is to entertain, enlighten and inspire people with his guitar playing.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)