How to solo over relative major and minor chords

It's one of the oldest tricks in the book, used by everyone from the Beatles to Neil Young and Pink Floyd, but playing around the major and minor tonalities can produce melodies that stick in the mind forever

Countless classic songs have been built using familiar combinations of relative major and minor chords. As you may know, if you start from a major chord, for example, G, its relative minor is rooted three half steps lower; in this case, that would be Em.

Likewise, if you start from a minor chord, say, Am, its relative major chord is three half steps higher; in this case, that would be C. Songs such as the Beatles’ This Boy, John Lennon’s Instant Karma, Neil Young’s Rockin’ in the Free World, Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here, Tom Petty’s I Won’t Back Down and many others are built from the shifting axis between relative major and minor chords.

The focus of this column is on devising melodies over relative major/minor progressions by connecting the common chord tones these pairs of chords share.

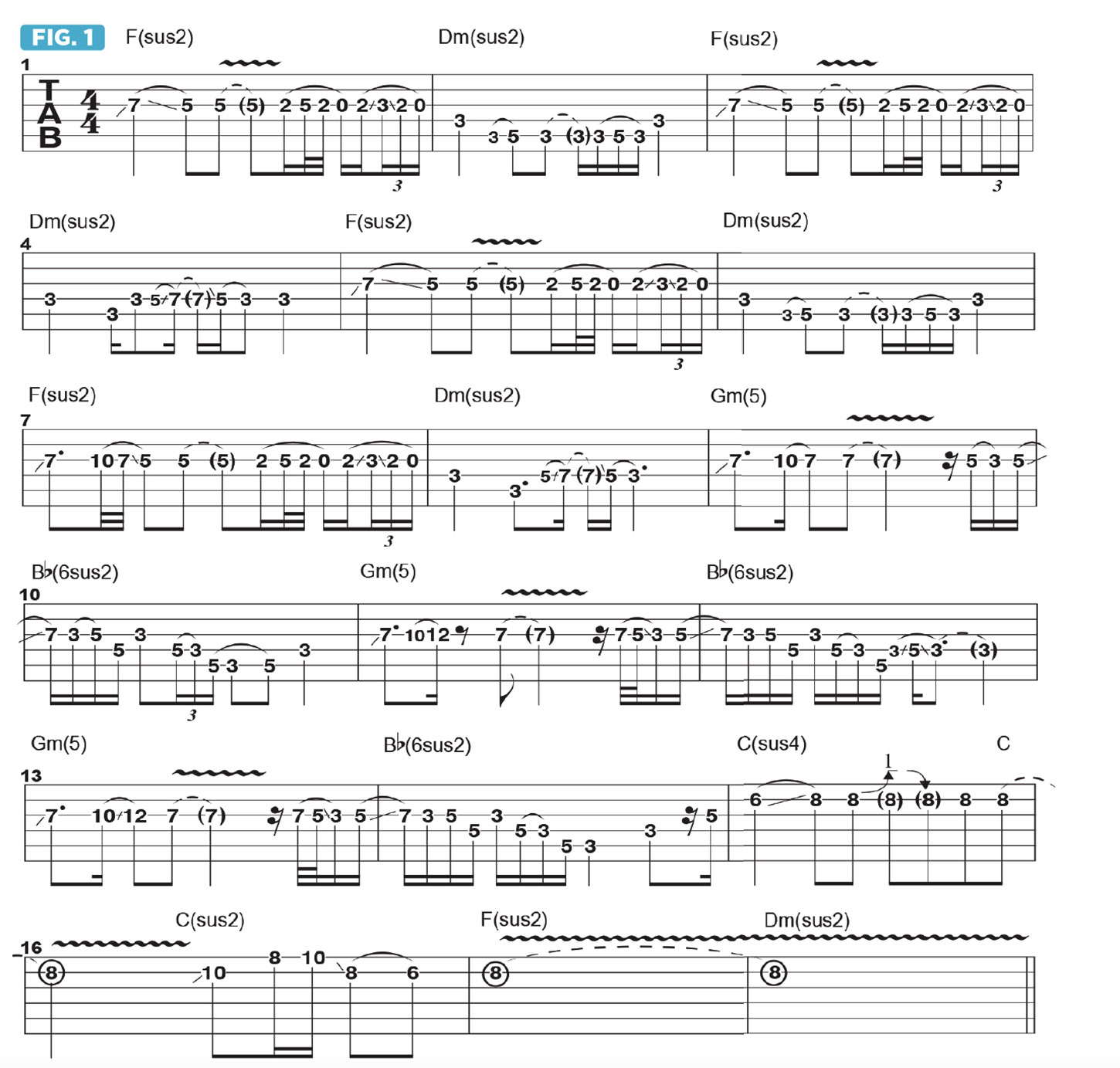

Figure 1 is a melodic line played over 16-bar chord progression that’s based on two different pairs of relative major and minor chords. The first eight bars are played over a repeating two-bar chord change consisting of one bar on F(sus2) followed by one bar on Dm(sus2).

Broadly, the melody is based on the F major pentatonic scale (F, G, A, C, D) over F(sus2) and D minor pentatonic (D, F, G, A, C) over Dm(sus2). As you can see, both scales are made up of the same five notes.

I introduce an extra note to F major pentatonic, Bb, which is the 4th of F. Adding this note gives us what’s known as the F major hexatonic scale (F, G, A, Bb, C, D). This scale works well over both F major-type and D minor-type chords, and other related chords as well, as demonstrated in our sample solo.

The articulation of this melodic line is essential to the way it is intended to “speak.” I begin with ascending and descending finger slides between D and C on the G string, followed by a double hammer/pull between A, C and G and then a double slide and pull-off between A, Bb and G. Utilizing slides, hammer-ons and pull-offs in this way is known as legato (smooth and connected) phrasing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

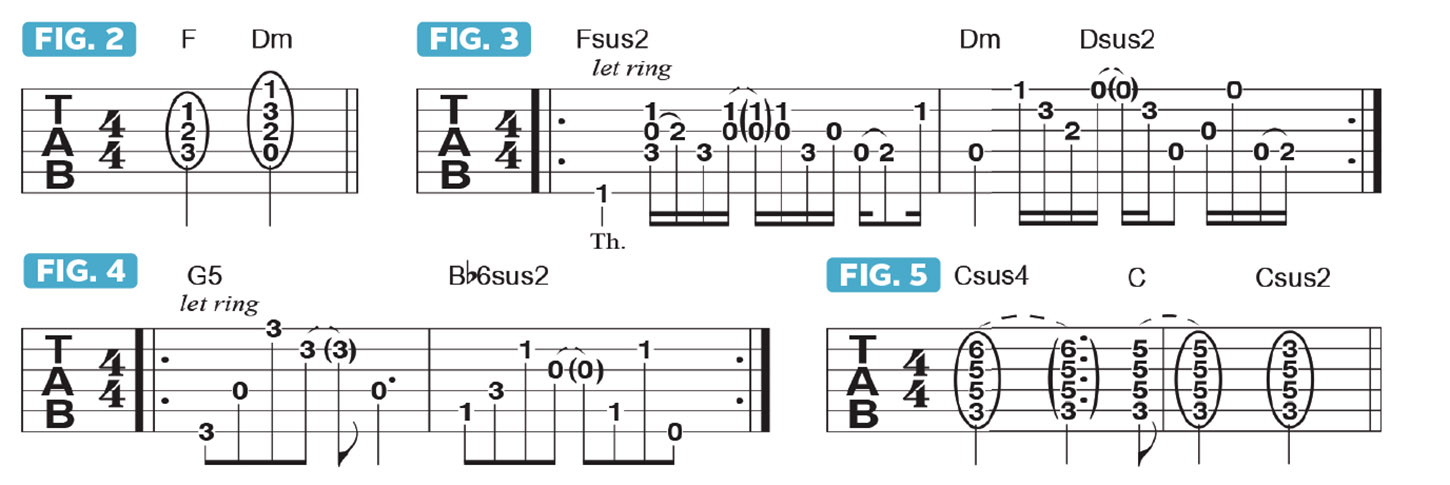

Figures 2 and 3 focus on F-to-Dm and how the rhythm pattern under the single-note line is articulated.

Bars 9-14 of Figure 1 modulate to the relative key pair Bb major and G minor, with the relative minor chord, Gm (actually just G5 here) occurring first, followed by Bb(6sus2). To improvise over these chords, I use the relative scales G minor pentatonic (G, Bb, C, D, F) and Bb major pentatonic

(Bb, C, D, F, G). As you can see, the two scales consist of the same five notes, starting from either G or Bb. Legato phrasing is employed once again for the lines played over these alternating chords. Figure 4 details the arpeggiation of the accompanying chord voicings I use for my backing track here.

The progression then wraps up with the V chord, moving from Csus4 to C to Csus2, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.