How to master arpeggios built from 7th chords

A little bit of theory goes a long way and can add tension and intrigue to your lead playing

A few columns back, I demonstrated a variety of ways to learn, practice and apply arpeggios based on triads. An arpeggio is defined as a “broken chord,” meaning the notes of a chord played individually and in succession. A triad is, as the name implies, a group of three different notes.

Most often, the term “triad”’ is used to describe the three notes that make up the most basic chord forms, which are major, minor, augmented and diminished, plus sus2 and sus4.

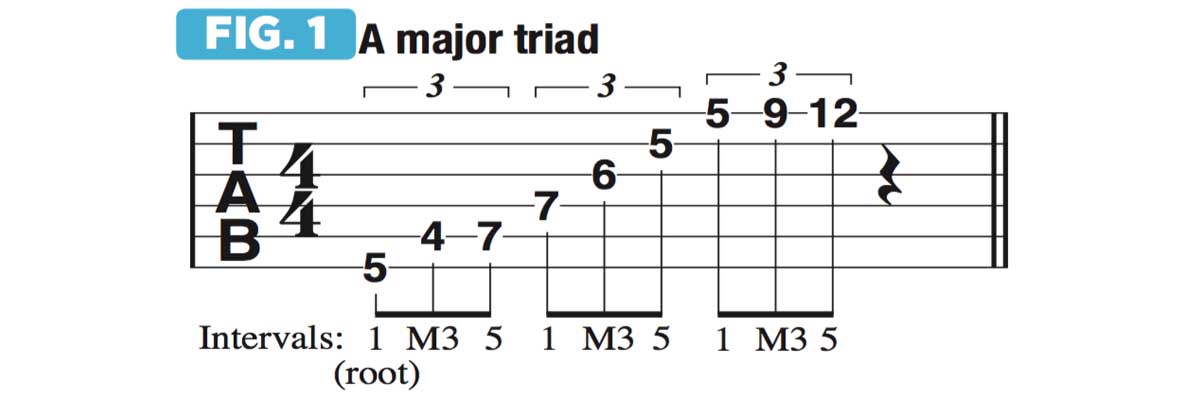

Figure 1 illustrates an A major triad (A, C#, E) played across three octaves. In previous columns, we examined chord progressions performed as a series of major and minor triadic forms.

Let’s expand our look at arpeggiated forms to 7th chords, which include an extra note. The most common triads are built from the 1st, 3rd and 5th degrees of a given major or minor scale (1-3-5, or 1-b3-5). As the A major scale is spelled A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#, the 1st, 3rd and 5th degrees are A, C# and E, respectively.

As you can see, this represents “every other note,” or notes that are two scale degrees apart, when starting from the “1,” A. We can easily expand to 7th-chord arpeggios by adding another note that is two scale degrees higher than the 5, or 5th.

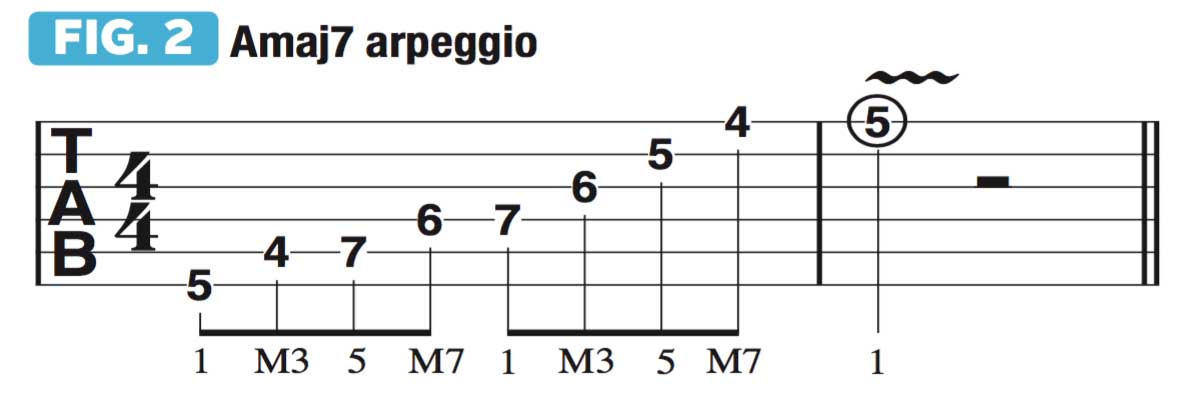

If we continue the “every other note” pattern, the result is 1-3-5-7. In the key of A major, those notes would be A, C#, E, G#. These are the notes of an Amaj7 (A major 7) arpeggio, which is illustrated across two octaves in Figure 2.

A great way to practice and memorize the Amaj7 arpeggio shapes is to play repeating groups of ascending and descending triplets. In Figure 3, the ascending triplet begins on the major 7th, G#, followed by the A root note and the major 3rd, C#.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The subsequent descending triplet starts on E (the 5th) and descends to C# and A, followed by a repeat of the first three-note pattern.

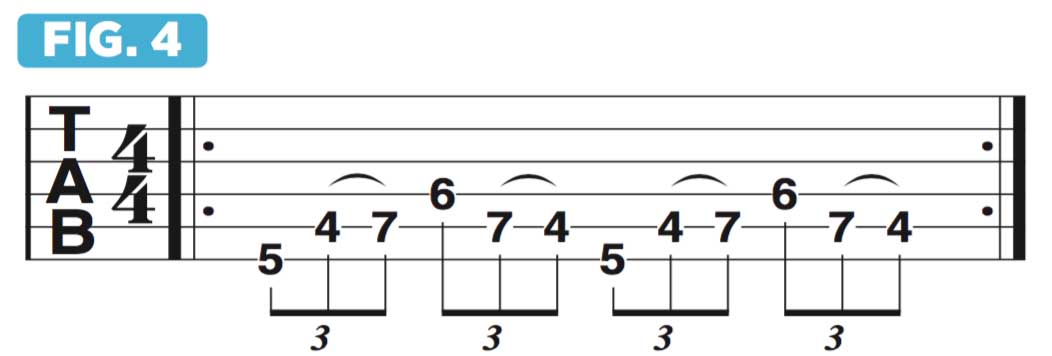

If we continually move up and start from each chord tone of the Amaj7 arpeggio (A, C#, E, G#) we’ll discover new three-note shapes. Figure 4 begins on the A root and ascends to C# and E, followed by a descending figure of G# - E - C#.

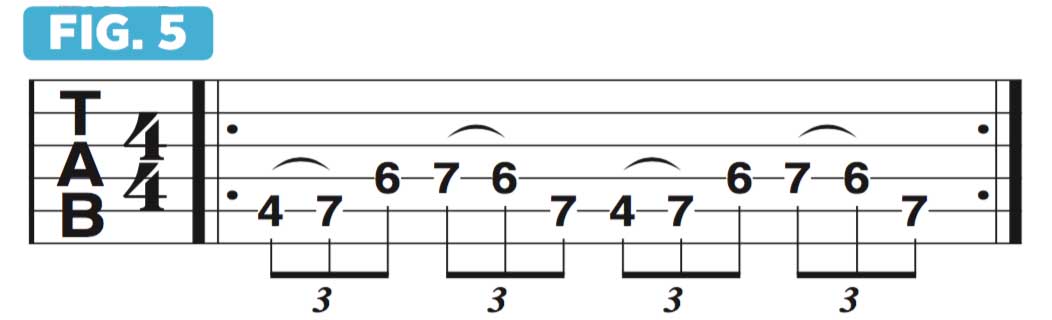

Figure 5 begins on the next chord tone, C#, and ascends to E and G#, followed by a descent of A - G# - E.

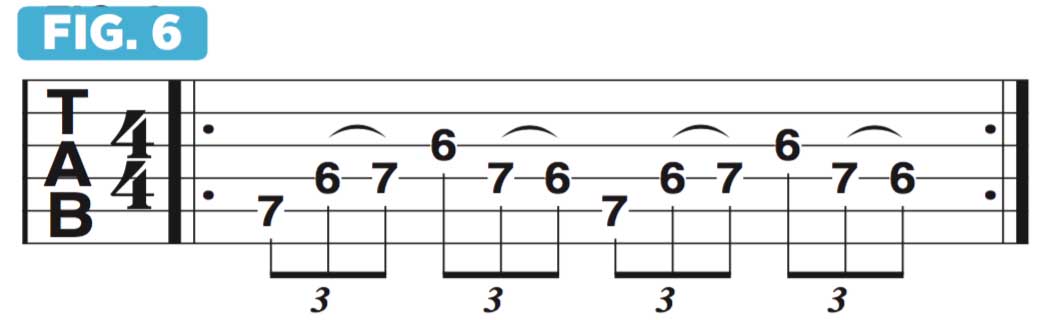

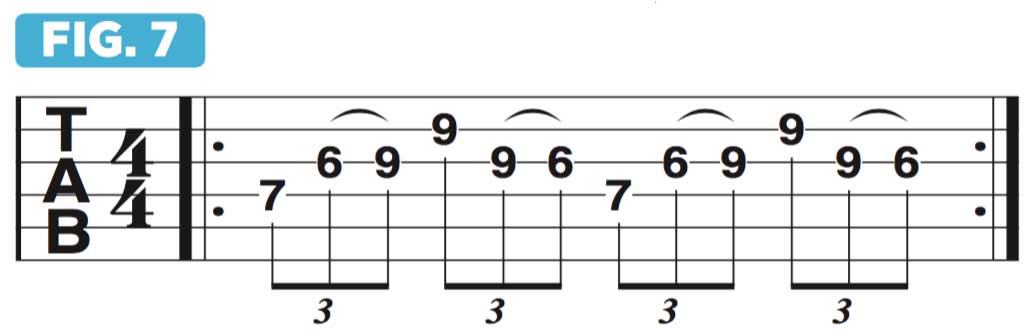

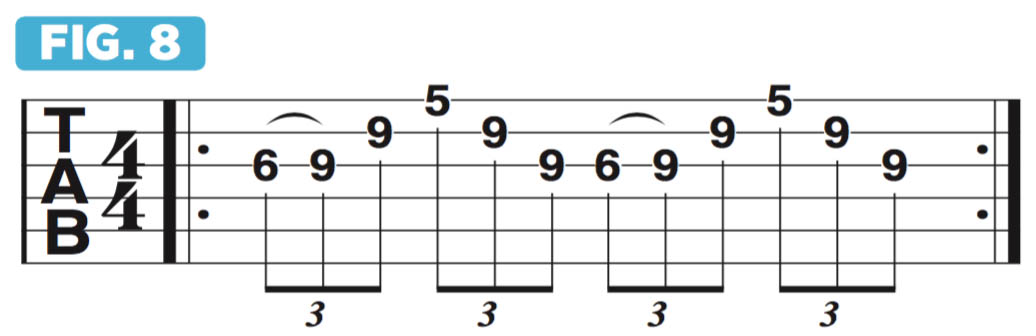

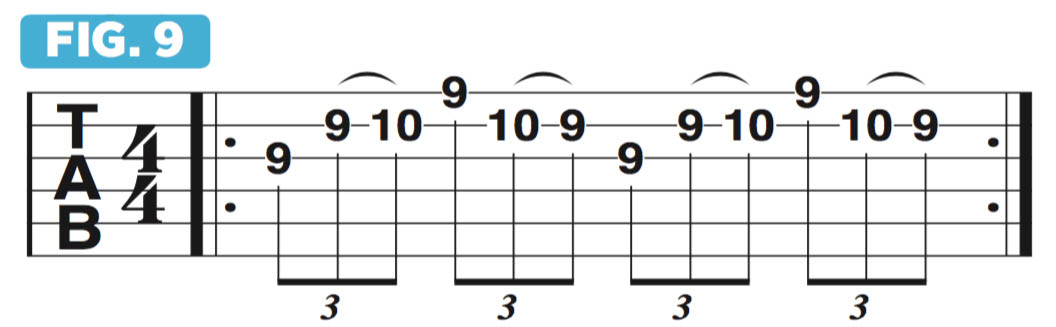

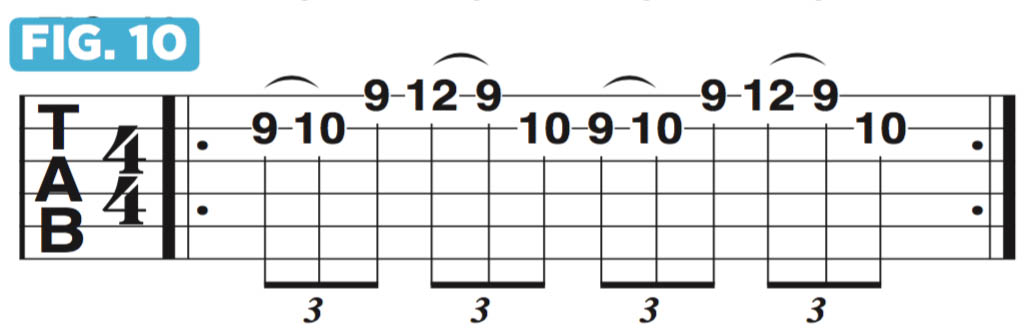

Figures 6-10 continue the process until we have played the initial form (G# - A - C# - E) one octave higher.

These 7th chord arpeggios can easily be expanded to include what are called the upper tensions or extensions, in the second octave of the form. This means that the initial 1, 3, 5, 7 chord tones of Amaj7 (A, C#, E, G#) will be followed by 9, 11, 13 in the second octave.

Keep in mind that 9, 11 and 13 are the same notes as 2, 4 and 6 (B, D and F# in this case) but played one octave higher. Figure 11 demonstrates how this works.

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.