How to get the most out of four-note blues solos

Because the best blues players know that less is more...

There are many tutorials that advise on how to expand your vocabulary in terms of extra notes added to pentatonic patterns, referring to implied chord extensions or even superimposing one implied chord over another.

While I’m a fan of these lessons, it occurred to me that it might be interesting to flip this approach on its head and go in completely the opposite direction.

To that end, I’ve chosen just four notes from the B minor pentatonic scale (A, B, D and E) and not ventured outside of this self-imposed limitation at all – not even to play these notes in different positions.

This approach forces you to think more and play less, and is a very worthwhile exercise

Doublestops, slides and string bends are all fine, so there is at least some room to expand, but the whole point here is to work with what we have.

I even decided not to use a pick when playing the example solo. The theory is that if we remove the pressure to play harmonically complicated or technically challenging phrases, it may focus the mind in a more ‘musical’ way.

A beginner could grasp the concept of playing just four notes (any of which will fit at any point over the backing), but the challenge is to bring dynamics, melody and rhythmic interest, using the skills we would normally bring to more technically advanced playing.

At first, this is really difficult! I’m reminded of picking up a Les Paul at the end of the 80s and constantly reaching for a whammy bar that wasn’t there. However, after a few minutes I stopped playing out of habit and managed to focus on working within this limited palette.

Admittedly, I haven’t left as much space between phrases as I might normally (demonstrating ‘silence arranged for guitar’ isn’t known for attracting readers…), but the way this approach forces you to think more and play less is a very worthwhile exercise. Hope you enjoy this approach and see you next time!

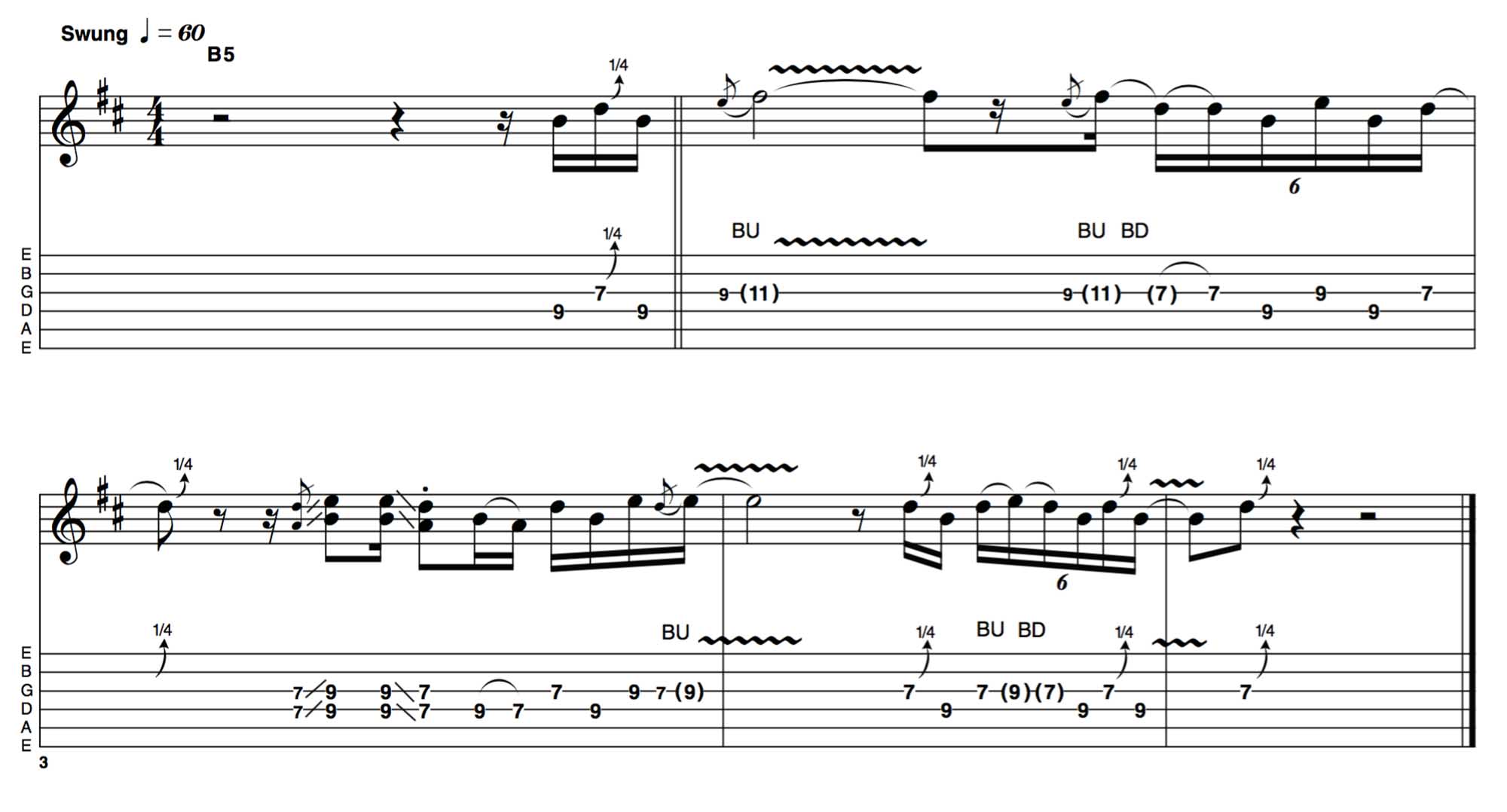

Example 1.

The first phrase establishes a few of the ideas used (some repeatedly) to take these four notes and turn them into music. It’s all about the inflections, via rhythmic phrasing and the manipulation of pitch with string bends.

This solo was actually more difficult to get on paper accurately than more traditionally ‘difficult’ phrases, which I guess means we’re dealing with musical content rather than scales - which is a good thing!

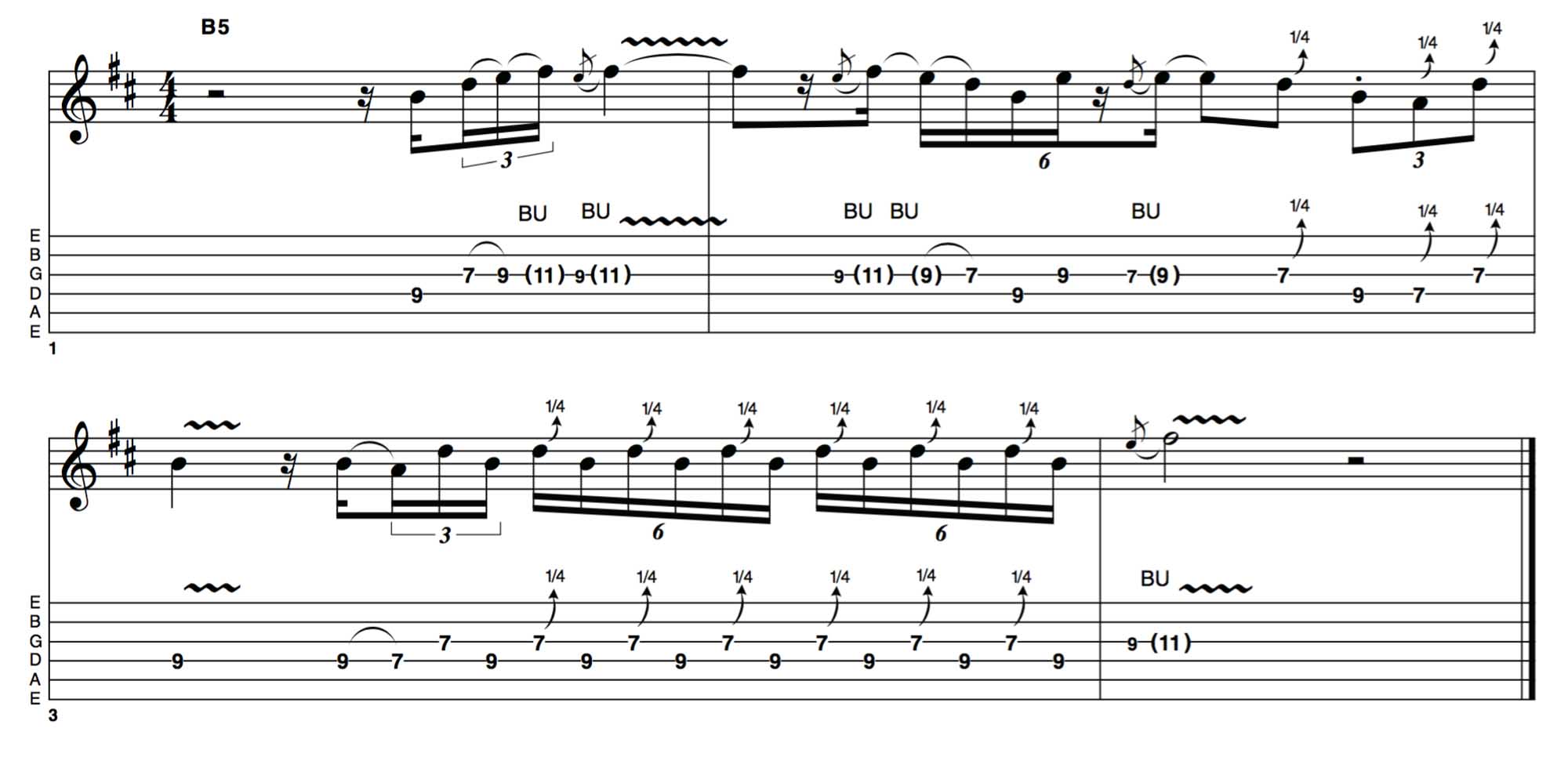

Example 2.

Although there's nothing wrong with simplicity or repetition, this phrase avoids too much of either by employing loud and soft dynamics, long held and short staccato notes, whole-tone and quarter-tone bends - which themselves vary.

A quarter-tone bend rarely means exactly that; it would probably be more accurate to say “slightly sharp," but that’s not a very practical system when writing music down. Other bends fluctuate between being as accurate as possible, sharp or flat.

Example 3.

If ever there was a demonstration of the quarter-tone bend in context, this is it! As with the previous examples, I’ve gone with string bends on both the 7th and 9th fret of the G string.

This seems more expressive than simply hitting D and E in sequence, though in the spirit of keeping things simple this does happen briefly at the end of the second bar, before heading into a sextuplet phrase similar to that in the last example.

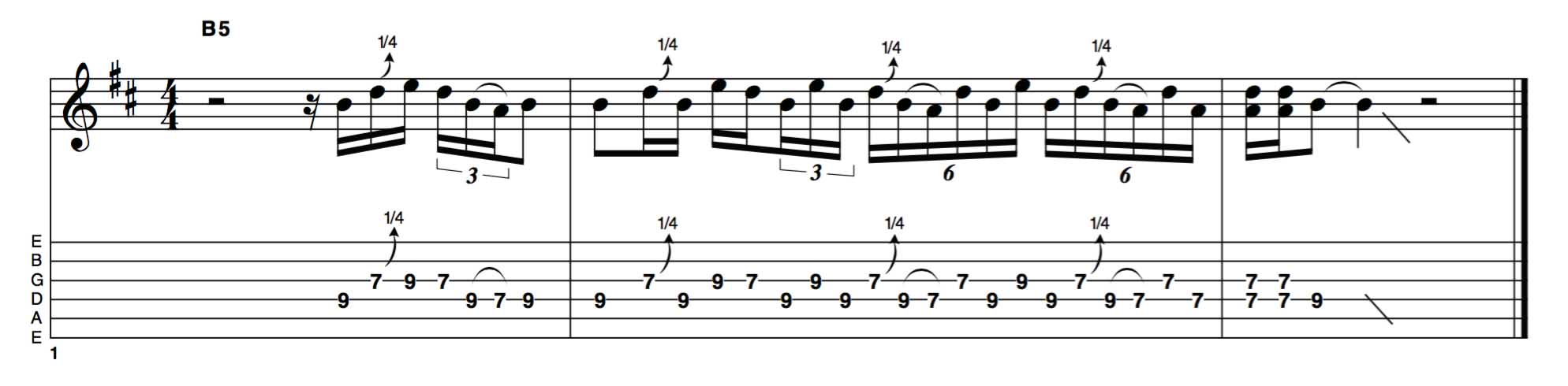

Example 4.

This example brings some variation to the sextuplet phrase, which I’ve leaned on fairly heavily in this solo to give a sense of dynamics, along with playing louder and softer. There are many more variants hidden away in this idea, of course.

And don’t forget the all-important space between phrases. This isn’t something I’ve featured too heavily here but it’s still an essential ingredient of a well-rounded and confident solo.

Hear it here

Albert King – Born Under A Bad Sign

It’s good to know the resurgence of blues music in the late 60s benefitted the original artists, as well as the new young torchbearers.

In 1967, Albert King released Born Under a Bad Sign. His minimalist style cuts through in the title track, plus Oh, Pretty Woman and Laundromat Blues, which showcases some of the super-wide string bends Albert was known for.

There are a few more notes at play here than in our example solo, but the approach is similar.

Albert Collins – Alive & Cool

Always cool, here we have ‘The Iceman’ live in 1969. The recording is pretty lo-fi, but that doesn’t take away from the experience at all.

Albert is in fine voice on both vocals and guitar on tracks such as How Blue Can You Get, Deep Freeze and Baby What You Want Me To Do.

Honorable mention should also go to the chilled Latin vibe on Mustang Sally - before it became known as a ubiquitous ‘function’ song.

Otis Rush – An Introduction To Otis Rush

I usually prefer not to go with any kind of compilation for suggested listening here, but the diversity of material from the different stages in Otis Rush’s career makes this an exception.

Check out his phrasing on I Can’t Quit You Baby, All Your Love and Crosscut Saw, the latter featuring some great examples of the minimalist phrasing/string bending that I’ve attempted to demonstrate in the example solo.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

“There are so many sounds to be discovered when you get away from using a pick”: Jared James Nichols shows you how to add “snap, crackle and pop” to your playing with banjo rolls and string snaps

Don't let chord inversions bamboozle you. It's simply the case of shuffling the notes around

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)