How to Solo Over “Busy” Chord Changes

Before we move on from the minor jazz-blues progression, which we focused on in the last three columns (see them under RELATED ARTICLES), I’d like to offer one more lesson on the topic.

It's built around another featured original solo, in this case played over the harmonically “busy” set of chord changes I presented as the second example two lessons ago (see “Adding tension,” January 2017 issue).

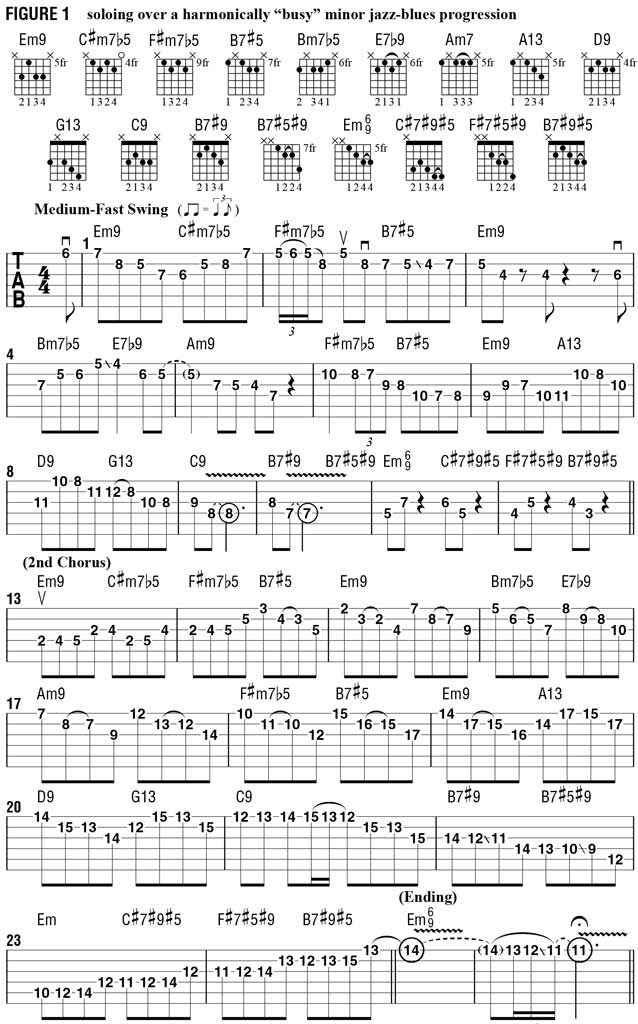

The solo, like last month’s, is played over a medium-uptempo swing groove in the key of E minor and spans two 12-bar choruses (see FIGURE 1). Only now, we have a lot more chord changes to navigate, with the goal of trying to acknowledge, or describe, them melodically.

With a few exceptions, almost every bar in this progression, which may be thought of as “minor blues on steroids,” includes two chord changes, making melodic improvisation and composition more challenging, in terms of reaction and action time.

As I almost always do in this type of situation, I’m strategically targeting a chord tone on each change, “hugging the navigational buoys” as I proceed through the “course.” Now you could very well just play E minor pentatonic or blues-scale licks over the entire progression and it would sound cool, but I think what I’m doing here sounds a little more interesting and musically compelling.

Here are a few highlights to this solo, which are good takeaways. The first involves the use of consecutive tritone intervals and substitutions, surrounded by space, which create an angular and quirky kind of sound, as demonstrated in bars 9–12.

The second is what I play over the progression’s numerous minor seven flat-five (m7b5) chords, or their substituted seven sharp-nine (7#9) voicings, for which I employ several different tactics—in bars 1, 2, 4, 6, 11–14, 16, 18, 23 and 24—that involve using either 1) the corresponding m7b5 arpeggio, 2) the Locrian mode (same set of notes as the major scale rooted a half step higher), or 3) the super-Locrian mode (also known as the diminished whole-stone scale, which is the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale rooted a half step higher).

Another highlight is the stringing together of minor-seven and dominant-seven arpeggios over the cycle-of-fourths root motion in bars 7 and 8, and again in bars 19 and 20, using either the natural or the raised, or “sharped,” second/ninth as a passing tone in each case. The star of the show, however, is the superimposition of a constant-structure descending minor add-two arpeggio shape, with a pull-off, that jumps around over all the various chords between beat three of bar 14 and the end of bar 18.

This kind of shape shifting technique is an exciting solo-building tool, one that gives melodic contour top priority.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)