Give your major-key compositions a moment of darkness by employing the 'four minor' chord

How borrowing chords from parallel minor keys can refresh your songwriting

Last time, I laid the theoretical groundwork for a look at some ways in which composers, when writing in a major key, have creatively 'borrowed' chords from its parallel minor key, which is based on the very same root note - for example, E major and E minor are parallel keys.

This is often done to insert a brief moment of musical darkness, or sadness, into an otherwise bright- and happy-sounding progression.

As promised, I’ll now reference some pretty well-known examples of this practice, starting with the use of the most widely borrowed chord in popular music, 'four minor', which in formal music theory is indicated by writing the lowercase Roman numeral 'iv', as opposed to the uppercase IV, which signifies four major.

The most common way the four minor chord is used in a major key is to play it after the four major (IV) and then follow it with one major (I), so that the progression goes four major, four minor, one major (IV - iv - I). There are countless examples of this clichéd but effective move in the vast catalog of modern music. Here are a few noteworthy ones:

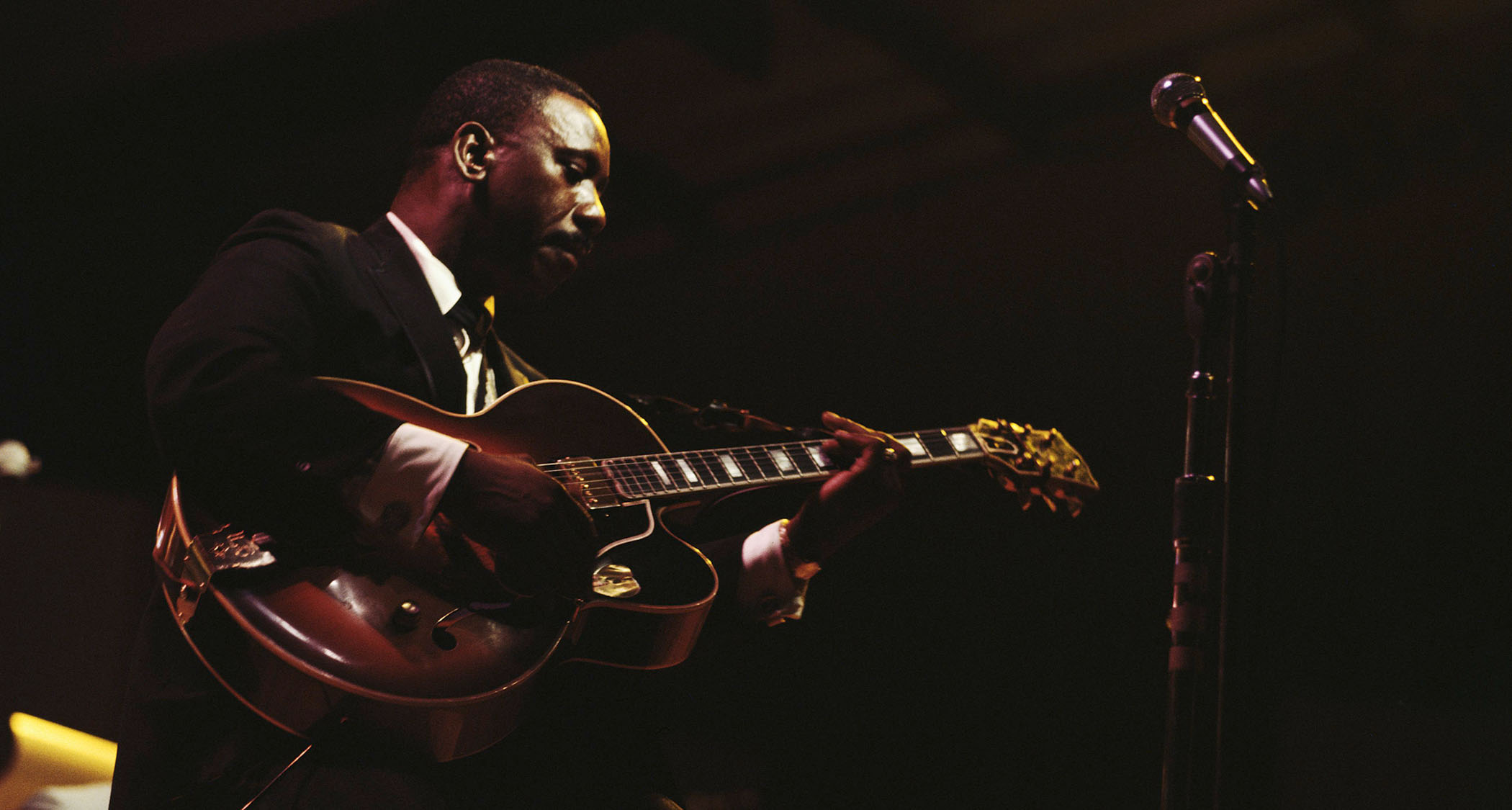

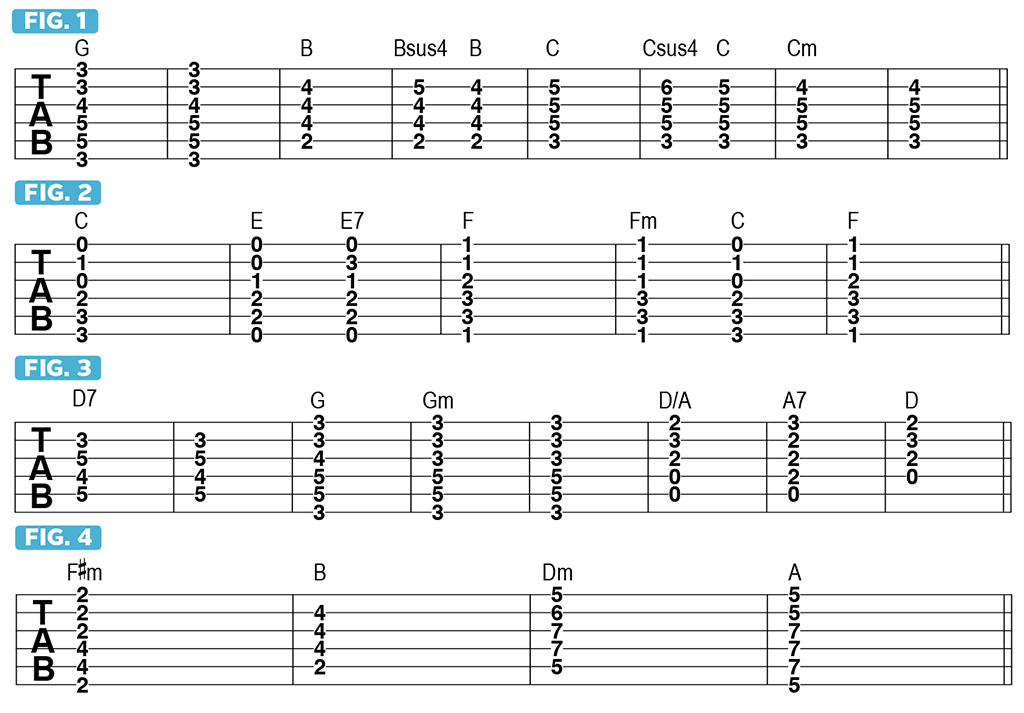

Creep by Radiohead is built entirely around a repeating four-chord progression in the key of G major that goes G - B - C - Cm, two bars on each chord. FIGURE 1 outlines the basic movement. It’s that Cm chord (first heard at 0:15 into the track), that gives the song its signature touch of melancholy.

Also in the key of G, the Eagles’ piano-driven ballad Desperado features a similar four-major-to-four-minor move - C to Cm - followed by a return to the one chord, G, first heard in the intro and again during each of the song’s verses, such as with the lyrics “why don’t you come to your senses,” with the Cm chord falling on that last word.

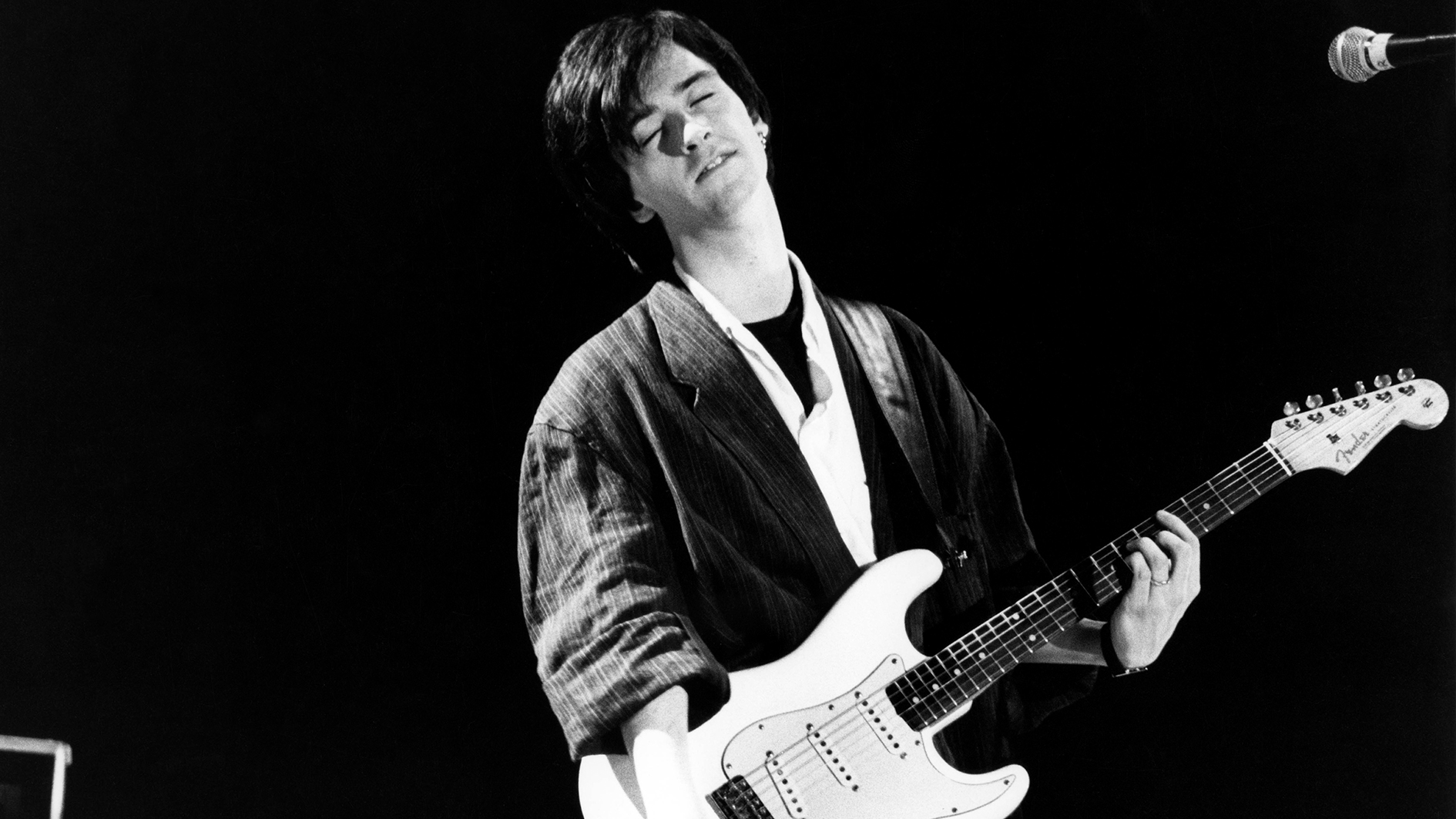

David Bowie used a similar progression to add emotional gravity to the verses in his classic Space Oddity, where, in the key of C major, the changes go C - E(7) - F - Fm - C. FIGURE 2 illustrates the basic movement.

Trey Anastasio of Phish, in the intro and verse progression to his beautiful acoustic-guitar-driven ballad Waste, employed this same IV - iv - I move (first appearing at 0:07), also in the key of C - F to Fm to C - as did Oasis in the pre-chorus to Don’t Look Back in Anger, first heard at 0:37.

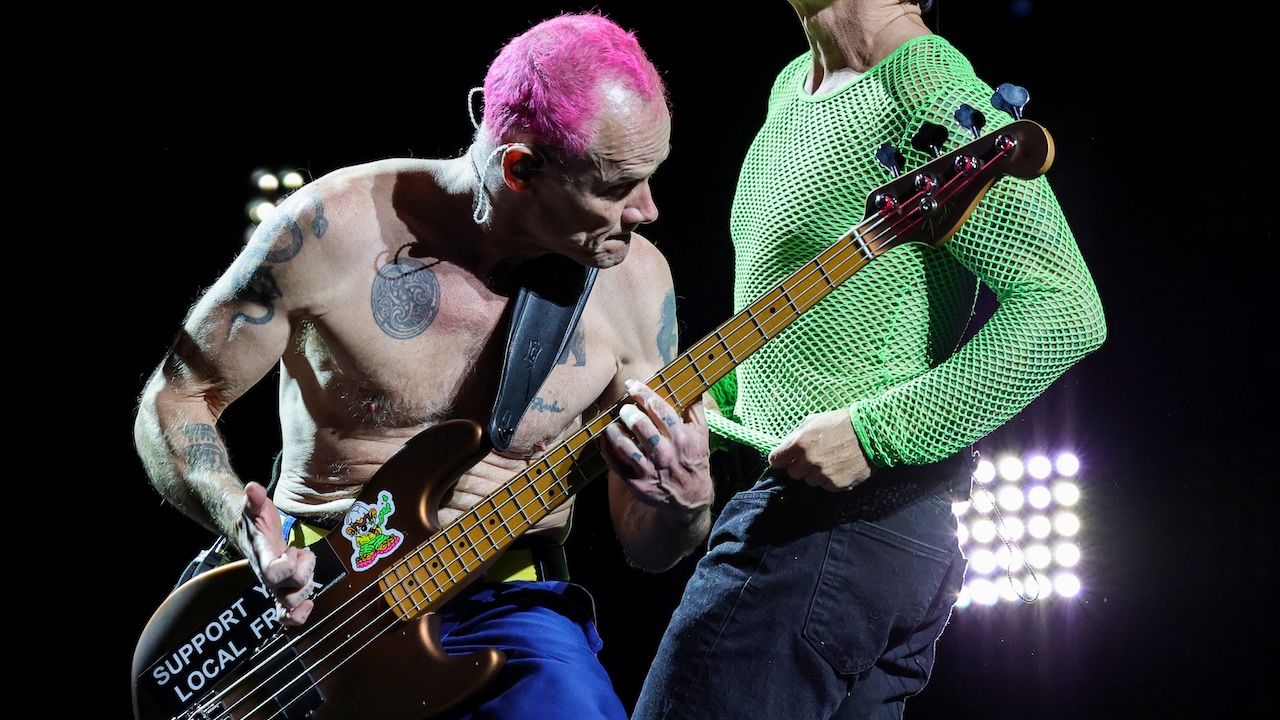

The great John Lennon used this same kind of 'four-major-to-four-minor' mutation, as it’s called (IV to iv) in several of his greatest songs with The Beatles, such as during the bridge section to If I Fell, specifically at 1:04, where, in the key of D, the progression goes D7 - G - Gm, then D/A (a D chord over an A bass note) to A7, which resolves finally to D, the one (I) chord. FIGURE 3 depicts a similar sequence, played as straight barre chords.

Lennon employed that Gm chord again elsewhere in If I Fell, but in a different way, skipping the four major chord (G) altogether and just going straight from one to four minor (D to Gm). The first occurrence of this is in the I - iv - V - I turnaround (D - Gm - A - D) played between the first and second verses, at 0:38.

The most poignant use of the four minor can be found at the end of the song, behind the words “if I fell in love with you, with the Gm chord played on “fell”.

In My Life, another of Lennon’s many early-Beatles masterpieces, offers two more great examples of the four minor chord’s use in a major key. One is during the verses (the first one beginning at 0:09), where, in the key of A major, the progression goes A to E to F#m, then A/G (an A chord over a G bass note), followed by D and Dm, then back to A.

The other usage of four minor (Dm) in this song can be found at the end of each chorus (at 0:37 the first time) and is brilliantly original, as Lennon goes from F#m, which, in the key of A, is the six minor chord (vi) to B, which would be considered two major (II), then, surprisingly, to four minor, Dm, which then resolves very sweetly to A. FIGURE 4 presents a basic barre-chord sketch of these cool and unusual changes.

Senior Music Editor “Downtown” Jimmy Brown is an experienced, working musician, performer and private teacher in the greater NYC area whose personal and professional mission is to entertain, enlighten and inspire people with his guitar playing.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.