Expand your creative arsenal by implementing the zero-th fret in your rhythms and leads

Explore open strings to create new textures, cluster chords, and scale voicings

It matters where we play our notes. Most of a guitar’s available tones can be fretted at several different locations - something impossible on pianos, saxophones, and most other instruments.

This opens us interesting creative choices - for example, there are five places to play the same B3 note, each with a different timbre, tension, and sustain (frets 19, 12, 9, 4, and 0 on the 6th to 2nd strings respectively).

We discover this idea very early on, learning to tune our guitars by matching the open strings to the 4th and 5th frets. But we generally neglect to explore the capability as much as we should from there - when soloing higher up the neck, the open strings tend to get forgotten. We rarely ‘look the other way’, missing out on a fascinating array of musical opportunities.

And there’s a lot of expressive power here. In fact, plenty of iconic guitar moments would lose their magic - or become unplayable entirely - if stripped of fret zero’s rich resonance (for just one example, the Crazy Diamond would lose a lot of its Shine).

This lesson will build your open-string awareness, allowing for new textures, patterns, and chord voicings. Your ear may find some of the movements counterintuitive at first, but they sink in pretty quickly if you play around with them enough.

Open string scales: the basic tones

First up, we should familiarize ourselves with the open string tones, and see how they relate to one another. There are five of them in standard tuning - E, A, D, G, and B, with another E on top. Together they form an Em(add11) chord, voiced as 1-11-b7-b3-5-1. Its harmonic vacancy allows it to ‘slot into’ several different common scale shapes.

Together, the open strings form an Em Pentatonic scale - play the string sequence 6, 3, 5, 2, 4, 1 for the ascent (also the notes of G major pentatonic). But hear how the constant zig-zag between low and high octaves removes a lot of the pattern’s familiar momentum. For such a simple shape, it can be hard to apply melodically. However, we can use these five basic tones to build fuller scale shapes, bringing stronger emotional resonances.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

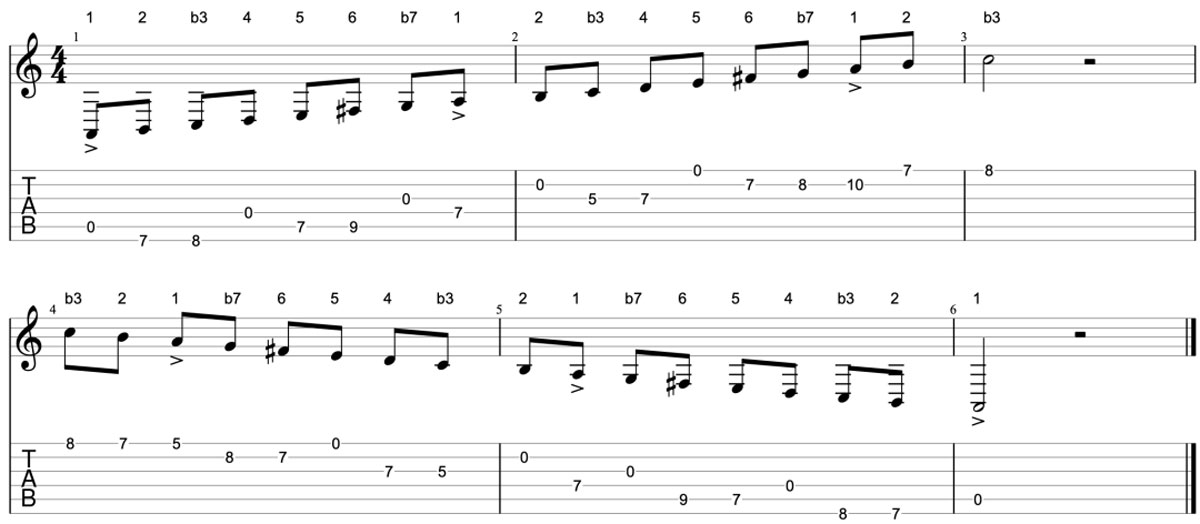

Ex. 1a - The ‘Harp Dorian’ shape

Our E-A-D-G-B note set fits right into in many heptatonic (seven-note) scales. Most importantly, they are all part of D, G, and C major, meaning they also match the following modes:

- Dorian in E, A, D

- Phrygian in F#, B, E

- Lydian in G, C, F

- Mixolydian in A, D, G

- Aeolian in B, E, A

- Locrian in C#, F#, B

Of these, I find that scales starting on the 6th and 5th strings are easiest to work with first, as you can anchor the unevenness of the other tones with a strong, low root. Out of this subset - E Dorian/Aeolian/Phrygian and A Mixolydian/Dorian/Aeolian - we will focus in on one particularly versatile way of playing A Dorian.

I call this shape the ‘Harp Dorian’, as it’s deliberately designed to maximize the use of open-string resonance, leaving as many harp-like ‘trailing notes’ as possible. Try it out - you have to keep things very accurate to get the full sustain, and might want to grip the fretboard at more of a right-angle than usual to avoid accidental string mutings. Listen to the strange textural unevenness and the swirling harmonic colour left at the end:

Hear how much of a difference the open strings make. Compare the orderly, ‘normal’ A Dorian shape to the uneven resonances of the Harp Dorian - recorded with identical guitar and amp settings:

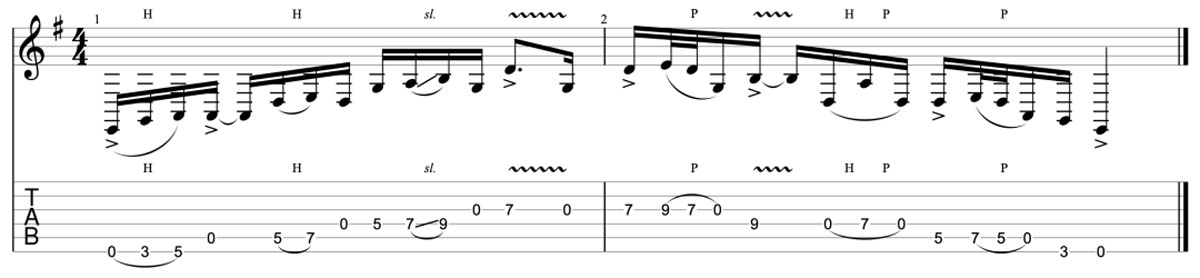

Ex. 1b - 'Harp Dorian' melodies

The key to improvisatory fluidity is to be able to ‘sing inside’. So move around the scale, familiarizing yourself with where each note lies and what happens when you jump between them.

You can write licks in the normal Dorian shape and then switch some of the notes to the open strings. Sometimes it works well, sometimes less so, but experimenting will increase your awareness. Here is one example of a standard A Dorian lick, again followed by its ‘harpified’ version:

Mess around with the scale pattern, and run through different ways of fragmenting it (e.g. ‘up three steps, down two’, or ‘skip every third note’). Find out what permutations sit best with your own musical inclinations - play around enough and the fluency will come.

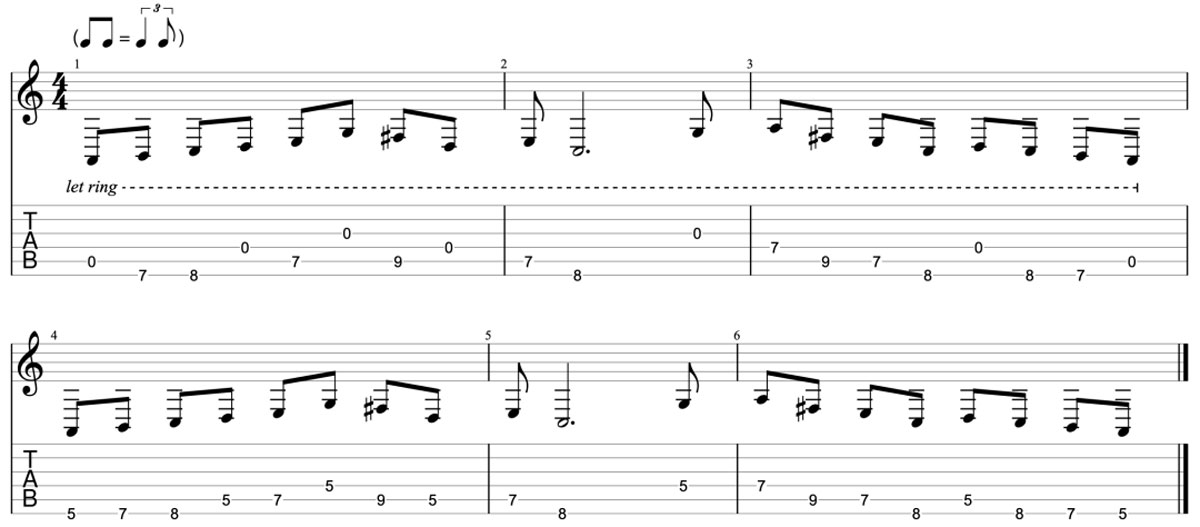

Ex. 2a - Adding open strings to Em Pentatonic

As mentioned, the five open tones of the guitar correspond to the notes of Em Pentatonic. This allows us to drop them into any other position of this scale without worrying that we’ll go out of key. The following pattern is one straightforward way of doing this - notice how this time, we don’t hold the open notes, only ‘pass through’ them:

Ex. 2b - Kaleidoscopic octave flurries

The real fun begins when we start adding embellishments. The shape above is crying out for some hammer/pulls, which allow us to create rapid-fire, heavily ornamented lines with ease. Here is one such take on the scale - it is ‘kaleidoscopic’ rather than ‘vocalistic’, built from cascading, unsingable patterns:

Ex. 2c - Ascent and descent patterns

You can move up and down the neck in similar fashion. The open string notes act like a physical ‘break’, giving you more time to switch between different strings and scale shapes. To demonstrate, here is the idea in a short question-answer lick:

Open-string pentatonic flurries are a great way to add intensity and general spice to your soloing (try them with a wah pedal...). But be careful how you use them - if you’re anything like me, it’s often tempting to just roll around through the shapes rather than focusing on the most musically coherent phrasings. After all, the more physically ‘guitaristic’ a pattern is, the more tactile satisfaction it tends to bring, and the easier it is to overuse. So always consider what a lick is saying, and how it creates tension, momentum, and release.

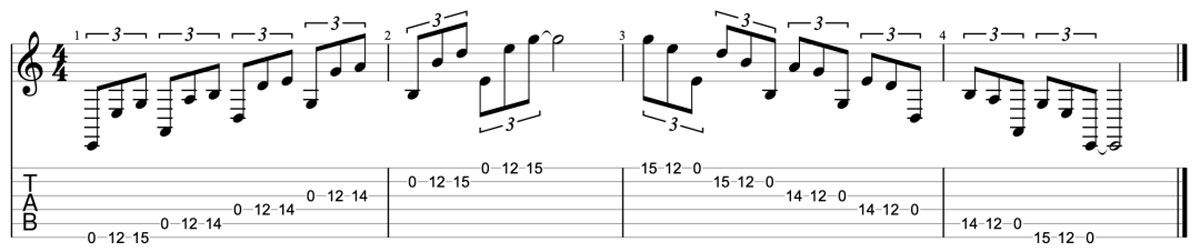

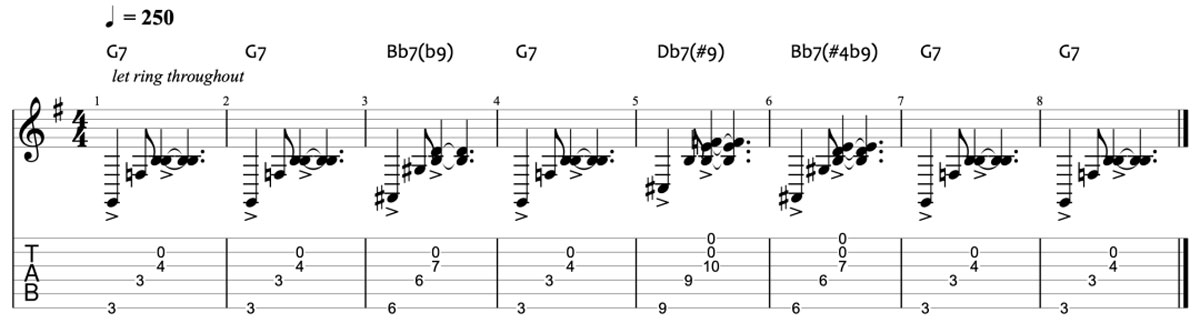

Ex. 3a - 12-bar ‘pedal point’ blues

Now we turn to some chordal ideas, applying open strings to a 12-bar blues. Here we use them subtly, adding an unchanging B tone on the open 2nd string. In European classical harmony, keeping one note constant throughout a deviating chord sequence is known as ‘pedal point’, although it is traditionally done with a droning bass tone (the ‘pedal’ of its name is that of the church organ).

The perpetually resonating B string recolours the basic blues chords without actually changing the harmony very much. The voicings are gradually extended, going from E7 to A9 to B7, then A11. The B string functions as the 5th, 2nd, and high root of E, A, and B:

The sound is floatier and more expansive than a standard blues rhythm part, with odd quirks and tensions. The A11 voicing in Bar 10 contains a ‘tone cluster’ - meaning that it has 3 adjacent scale notes in the same octave (the C#, D, and E on strings 1-3). Hear how the slight overdrive really brings out the dissonance of it. While easy on a piano, the guitar’s wide tuning means that tone clusters are difficult to reach without incorporating the open strings.

Ex. 3b - 8-bar ‘deranged’ blues

Try playing basic chord progressions in different keys, getting a feel for which shapes work best with which open strings. Here is one variant I particularly like, which adds the same open B string to a ‘deranged’, diminished bluesy pattern in G, with root movement in minor 3rds.

Some of the basic shapes become more markedly misbalanced by the B than in the example above (this time it is the 3rd, b9th, and b7th of the chords), again accentuated by the overdrive. But the constant tone also brings a harmonic consistency to proceedings - everything but the B is in a constant reshuffle, pivoting around this static tone.

And while most constant tones we come across tend to be low drones on the root, this one is a high 5th (a.k.a. a perfect 12th):

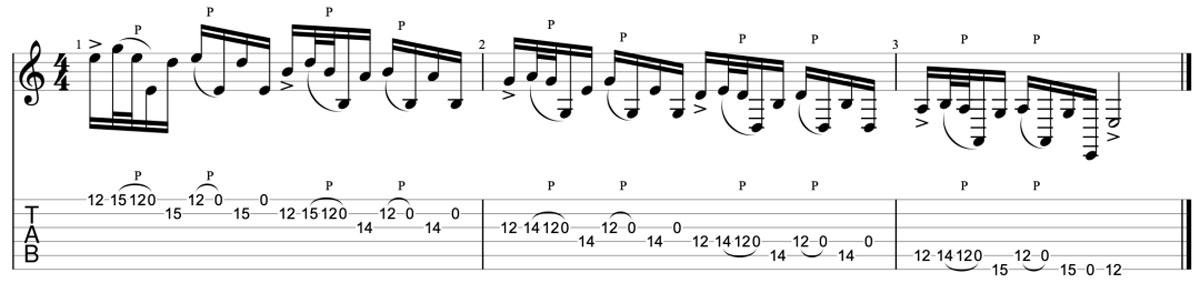

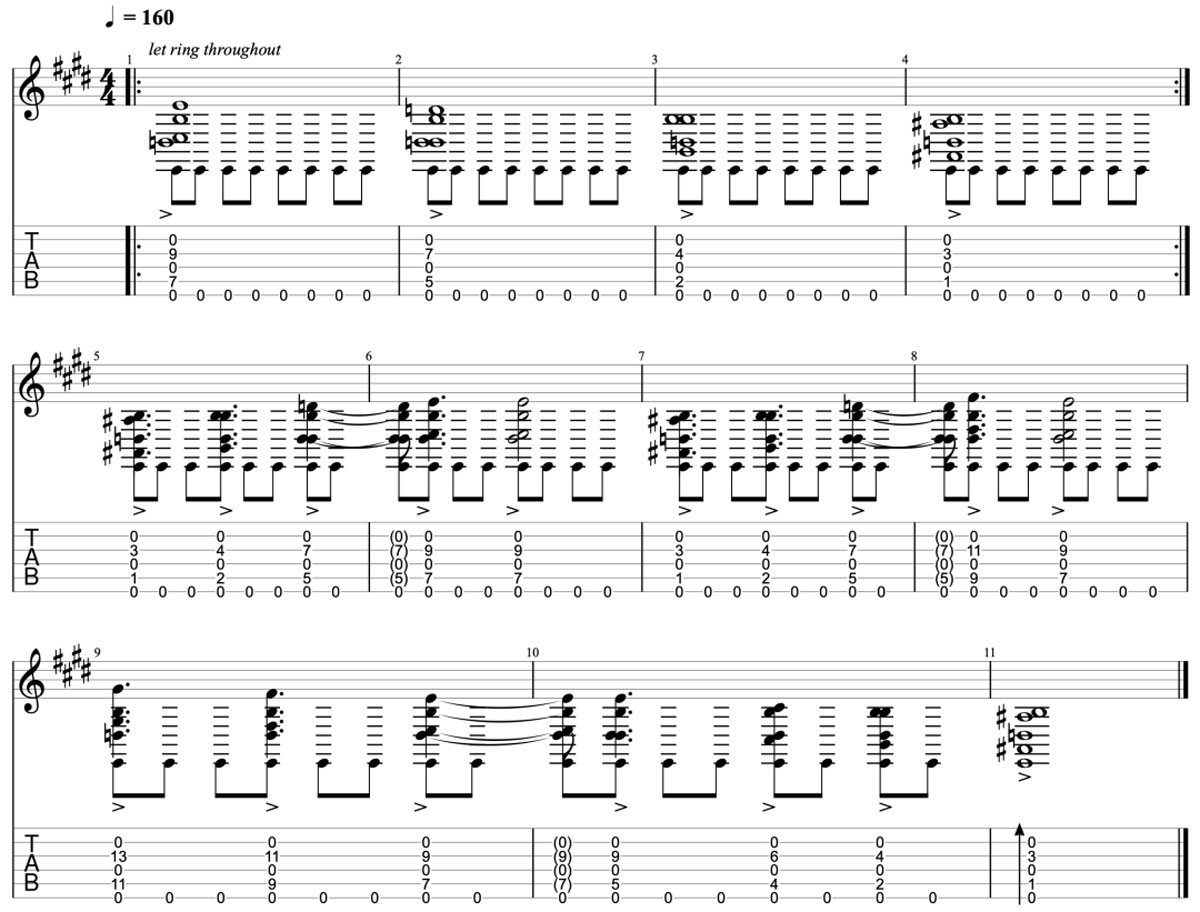

Ex. 4 - Vertical octaves in Raag Vachaspati

Finally, we will explore another dimension of open string playing - the ability to really let loose with our strumming. We do this sort of thing from the very start with the beginner chord shapes, straining in our early days to make sure each unfretted string is resonating properly.

We can also strum hard using octaves. The exercise below draws on the vertical approaches of Indian classical music. When learning the sitar I quickly discovered that virtually all played up and down just one of the 23 strings, with the rest being used for harmonic texture and percussive emphasis.

(See my article on the sitar for more, as well as previous guitar lessons on Raga Basics and Hindustani Melodic Ornamentations.)

We can replicate some of this vertical, sitaristic feel by using octaves fretted on the 5th and 3rd strings. Placing them here removes the open A and G tones from the equation, freeing us up harmonically (A and G are the 4th and b3rd in the Em Pentatonic, arguably its most dissonant notes).

In this exercise, we use this freedom to explore a curious framework - the Lydian Dominant, ‘Overtone’ scale (1-2-3-#4-5-6-b7 - mode 4 of the Melodic Minor). Known as in India as Raag Vachaspati, it is more familiar to Westerners as the basis for Danny Elfman’s The Simpsons Theme:

As ever, play around with different intervals and see what you come up with. Don’t think about things in terms of exact harmonic interrelations, just consider how each octave position has its own level of ‘crunch’ (e.g. compare the pure consonance of the very first chord with the clashing dissonance of the very last - wholly dictated by their relation to the open strings). Think carefully about how much overdrive to use - I’ve over-spiced things a little to highlight the contrasts.

It’s important that we use the guitar’s characteristic strengths in our playing. This sounds obvious, but I’ve heard a few jazz guitarists say that use of the open strings is limiting, as we can’t transpose our lines so easily that way (“the ideal is to play like a horn, man”).

While I love learning moveable horn lines, I feel that it’s just one of many approaches (why wouldn’t you use all the tools available to you?). We’re guitarists, and should call on the unique facets of our instrument - so, don’t forget the power of the zero-th fret. These are just a few of the countless ideas found there.

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.