Enrich your solos by incorporating major pentatonic and hexatonic scales

Diversify your compositional palette with this essential primer

Understanding major-type scales is an essential element in learning to solo on the guitar. The seven-tone major scale, also known as the Ionian mode, contains all intervallic degrees within a given octave; in simple numbers, 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (8).

The specific designations for the major scale are 1 (root note), 2 (major 2nd), 3 (major 3rd), 4 (perfect 4th), 5 (perfect 5th), 6 (major 6th) and 7 (major 7th). The formula that describes the distance, or intervallic measurement, between the successive degrees of the major scale, indicated in whole steps and half steps, is W, W, H, W, W, W, H.

That means that there’s a whole step (W), the equivalent of two frets, between 1 and 2, between 2 and 3, and between 6 and 7, and a half step (H) between 3 and 4, and between 7 and 8, with 8 being the root note (1), one octave higher.

When it comes to improvisation, the major scale is often reduced to a smaller subset of notes, such as the five-tone major pentatonic scale, spelled 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, or the six-tone major hexatonic scale, spelled 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

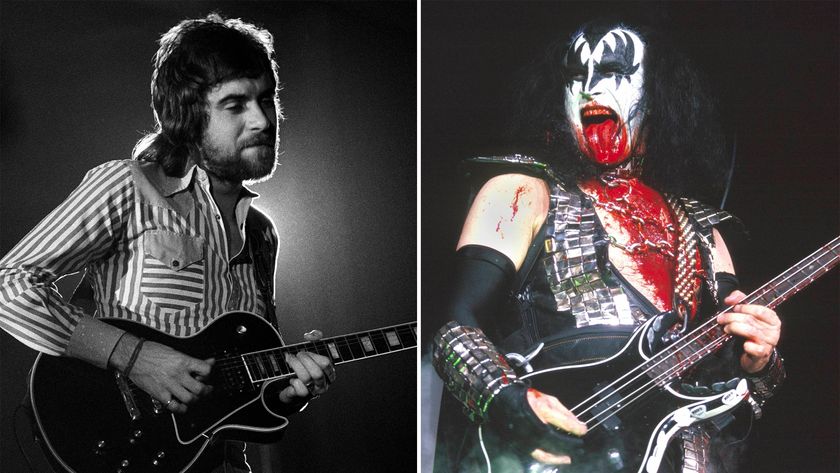

Major pentatonic, and its relative mode, minor pentatonic, form the bedrock for soloing in blues and rock, and examples can be readily found in just about every solo by guitarists such as B.B. King, Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton.

Two legendary players, Duane Allman and Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers Band, relied upon the major hexatonic scale so often, most notably in the ABB classics Melissa, Blue Sky and Jessica, that it is referred to by many as the Dickey Betts scale, since Betts wrote these songs.

In the previous two columns, I presented all the fretboard positions for the E major pentatonic and hexatonic scales, so now let’s put these overlapping scales to use in an improvised solo.

FIGURE 1 illustrates a repeating chord progression along the lines of that heard in the solo section of Melissa, and FIGURE 2 offers an eight-bar improvised melody played over it.

Bar 3 begins with a shift from 2nd position up to 4th, via a finger slide, followed in bar 4 with a shift up to 7th position and then quickly back down to 5th and 2nd positions.

Bar 5 illustrates the usefulness of the open top two strings when soloing with these scales, and bars 6-8 utilize quick shifts between 2nd, 4th and 6th positions.

Let’s now take a similar approach with scale patterns located higher up the neck. FIGURE 3 begins with E major hexatonic lines in 4th position, played mostly in straight 16th notes, and bars 3 and 4 employ upward shifts to 5th, 9th and 12th positions. Bars 5-8 then have us moving in a seamless manner between the 9th and the 12th positions.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.

Want to play Master of Puppets the right way? Here's how to get faster at downpicking so you can chug like James Hetfield

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe-840-80.jpg)

“The intensity of Rory’s guitar playing – the emotion, the sound and his incredible attack – was mindblowing for me”: Joe Bonamassa pays tribute to the late, great Irish blues-rock icon Rory Gallagher