How to introduce “murder mystery” guitar chords to your playing – without getting your fingers in a twist

Altered chords should not scare anyone. Here are five shapes to explore when looking for a chord with some dramatic dissonance

In my previous column, we looked at the difference between extended and altered chords, and I wanted to give some further examples and explanations of how altered chords work in practical terms.

After all, the guitar can be a tricky instrument on which to conceptualise music theory! All but one of the examples here have been altered – namely, at least one note has been raised or lowered from where you would normally expect to find it in the ‘parent’ scale. We’ll talk about which one is the odd one out (and why) later.

We can get some pretty dissonant ‘murder mystery’ type chords without having to get our fingers in a twist.

However, most chords don’t present themselves to us neatly on the fretboard in linear scale order in the way in which they do on the piano keyboard. This can be off putting until you realise that virtually all altered chords are based around a small selection of more familiar shapes. Have a look for yourself.

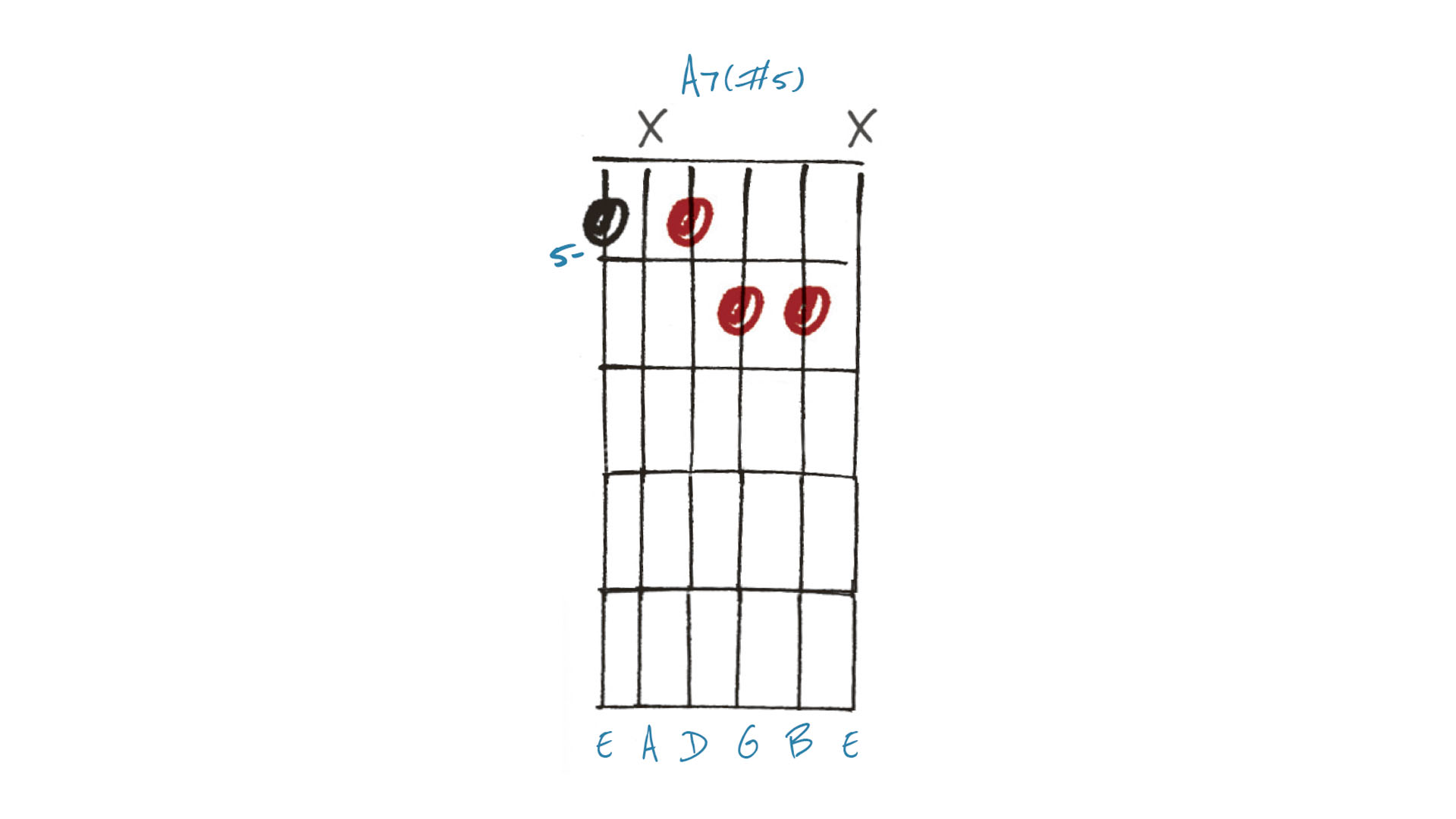

Example 1. A7(#5)

Based on the regular A7, this version omits the 5th (E) you might normally expect to find on the fifth string, but if we look at the second string there is a #5 (F) at the top. A #5th is often referred to as augmented, so if you see A7(aug 5) on a chord chart, this is it!

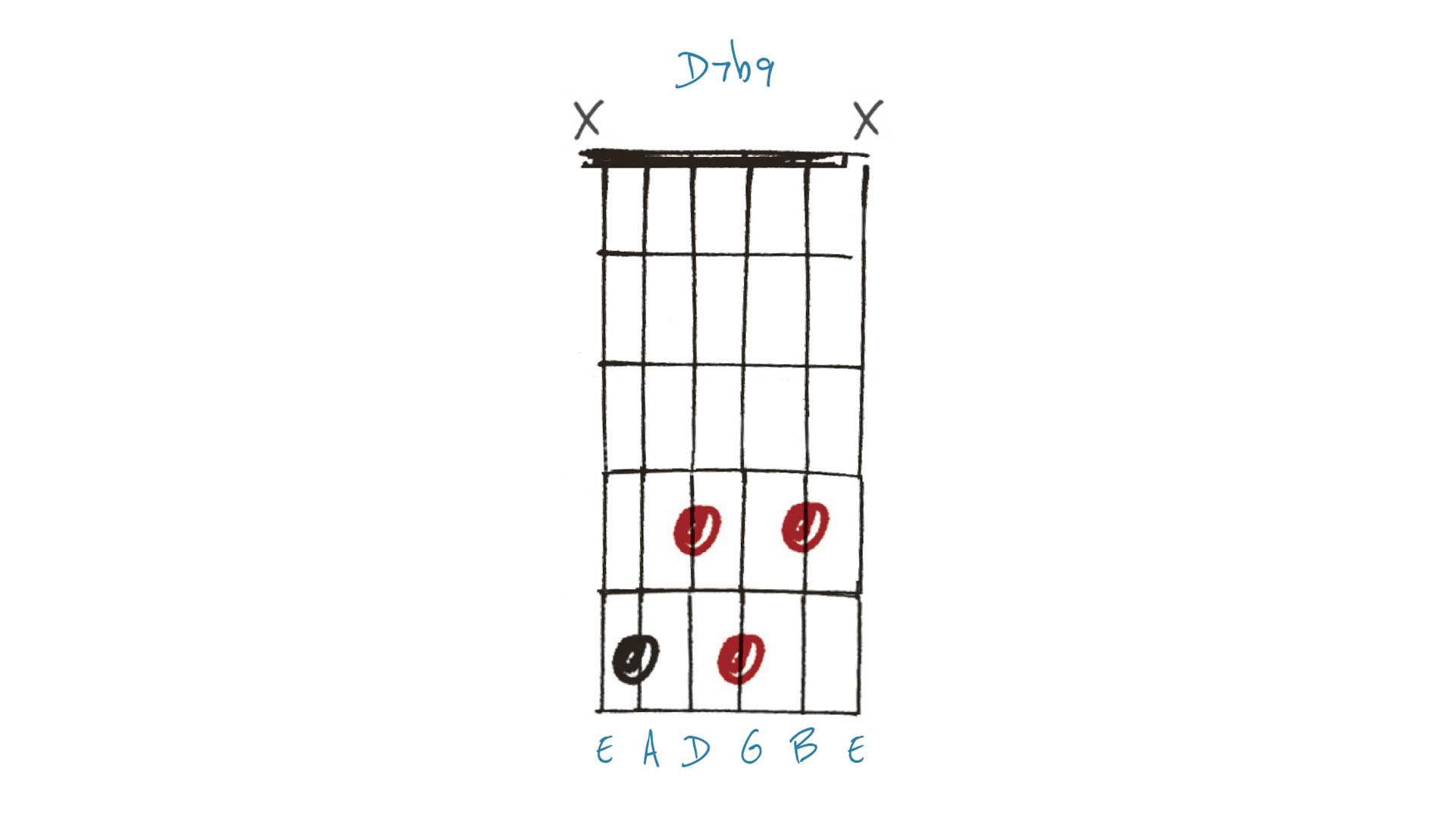

Example 2. D7b9

This would be a D9 chord, but if we look at it from low to high, we have: root (D) - major 3rd (F#) - dominant 7th (C) - b9 (Eb). The Eb/b9 is the note that makes this an altered chord. Play this after a D7(#9) and end with E minor and you’ll recognise a fragment of Pink Floyd’s Breathe.

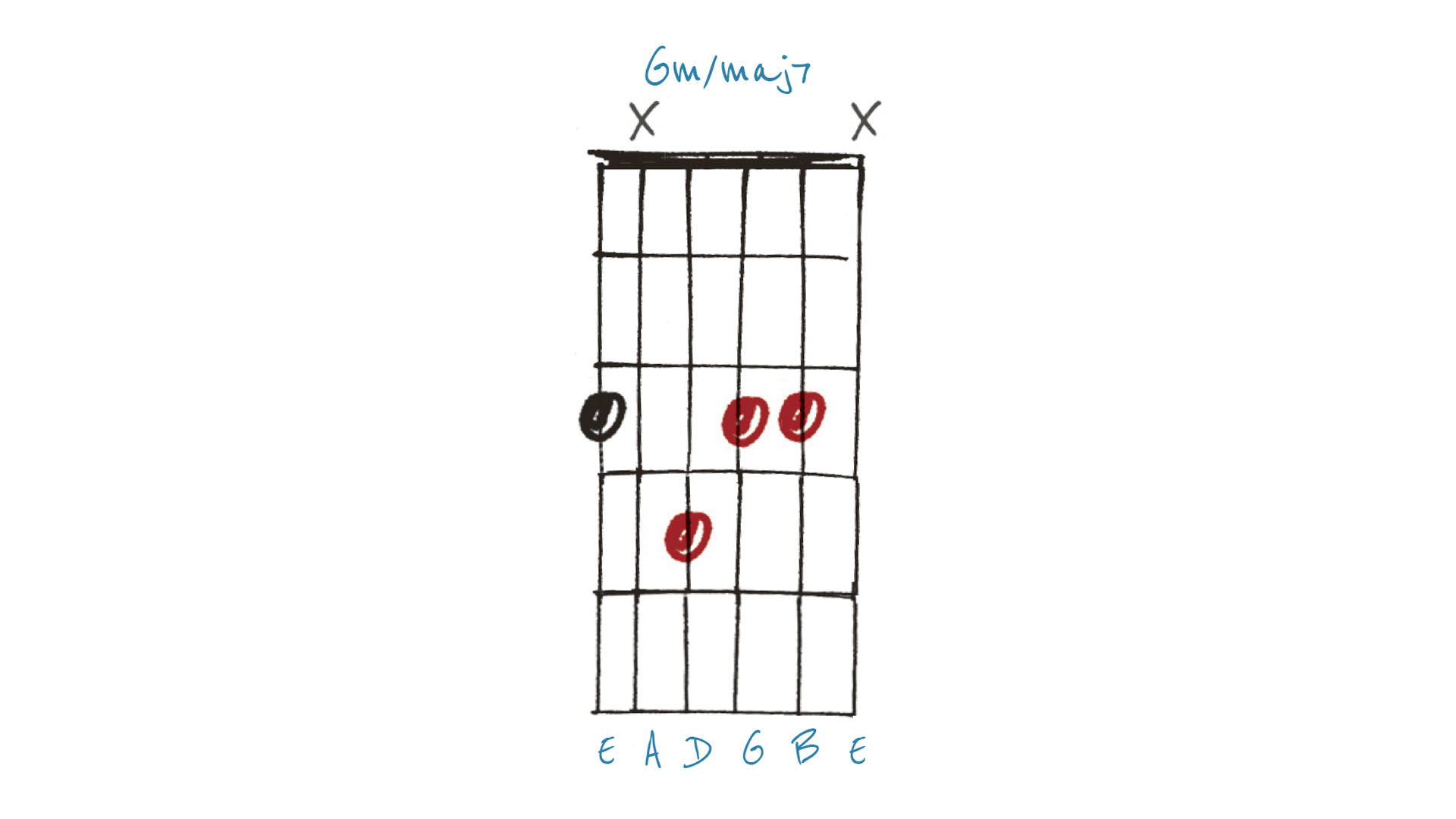

Example 3. Gm/maj7

This is based on a Gm7 chord, but instead of the dominant 7th (F), this features a major 7th (F#). We’ve just found the odd one out! A b3rd does not count as ‘altered’ in the theoretical sense, neither does a dominant/b7 or major 7th. Still a great chord, though.

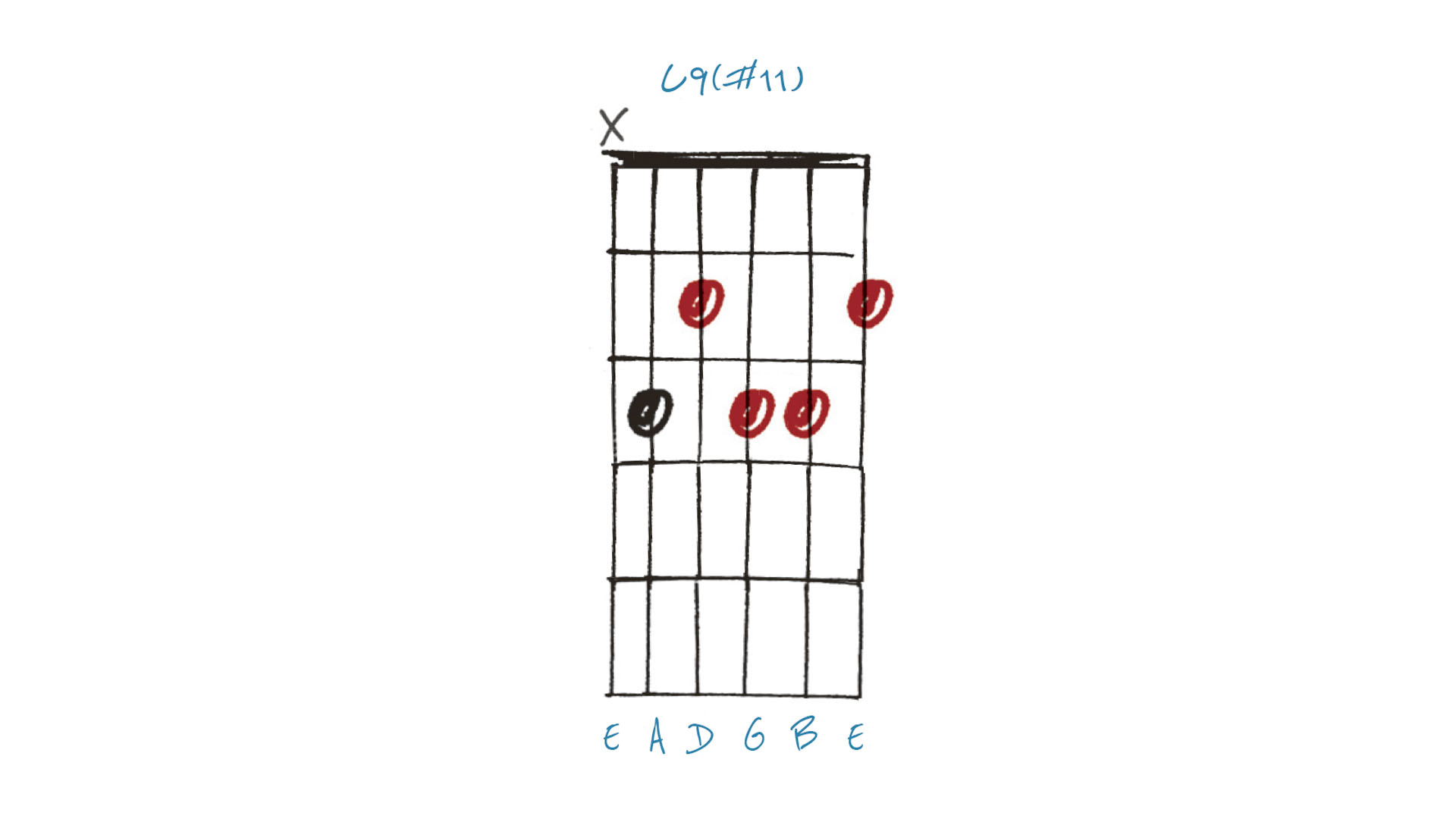

Example 4. C9(#11)

If you rake down across the strings slowly, this sounds like a regular C9 chord. However, once you get to the first string, that F# is raised, as opposed to the F you usually find in the C major scale. That’s why this is an altered chord. It’s much nicer than adding a regular 11th (F) on top.

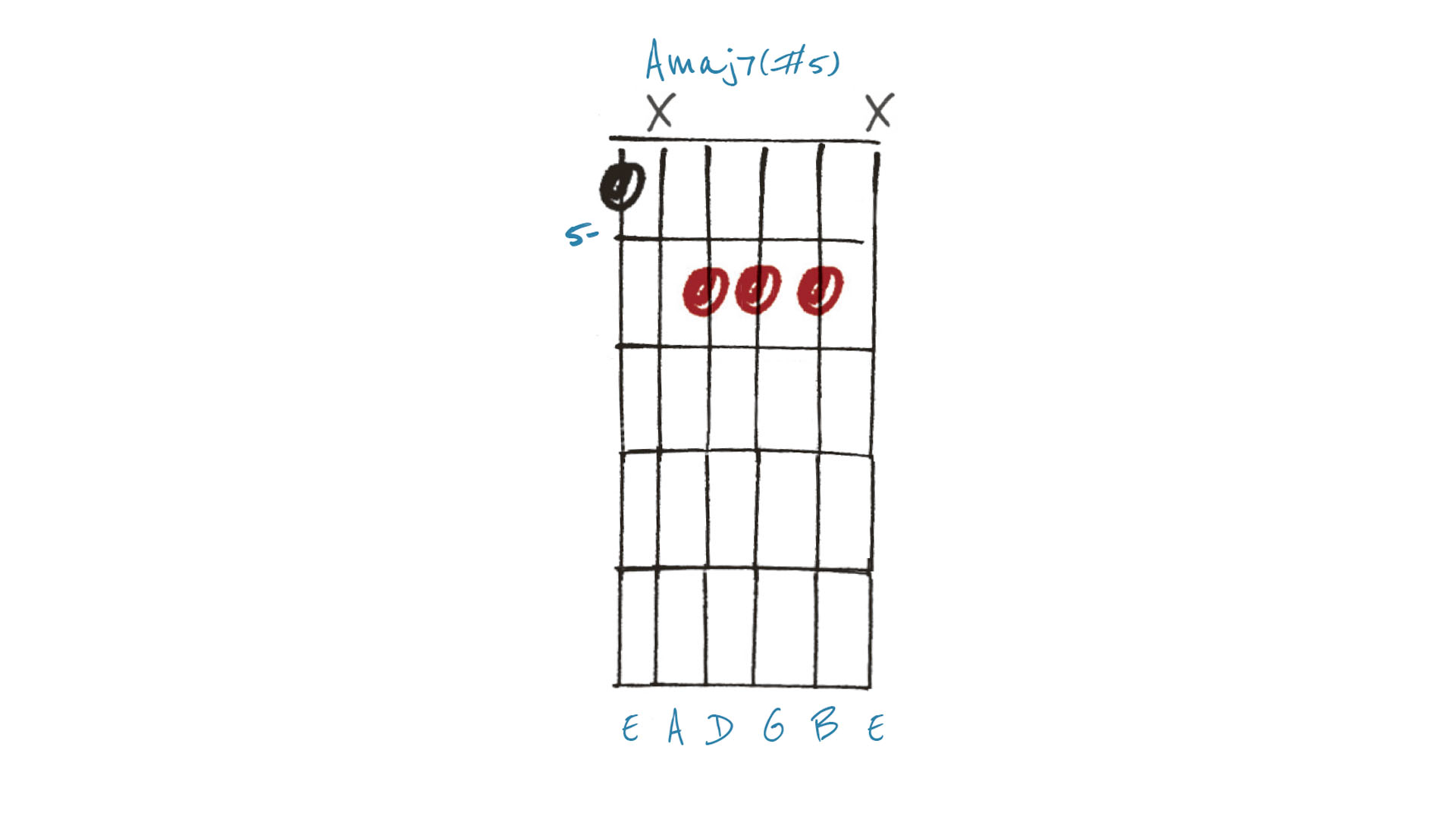

Example 5. Amaj7(#5)

This very dramatic chord is an Amaj7(#5). Shifting (altering) the 5th up a semitone from E to F on the second string takes us from pretty love songs to ‘murder mystery’ territory. It’s worth noting that using a dominant 7th in this chord (G) would bring us back to the A7(#5) of Example 1.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)