Bring a new dimension to your acoustic playing with this guide to percussive guitar techniques

How you can better utilize the acoustic guitar's rhythmic capacity

Every acoustic guitarist has experimented with the percussive tones of the instrument’s body. Not only is this inevitable - we’re all clumsy sometimes - it’s also an expression of something much more fundamental. Rhythm is, in many senses, the most basic element of music. As children we cannot help but bang on the objects around us - drumming is a vital part of how we learn about the world.

This innate percussive inclination is true all across the world. I was recently discussing North Indian rhythm with Debasmita Bhattacharya, a virtuoso of the Hindustani sarod (23-string fretless lute).

In her words, “Rhythm...is the closest part of music to nature, as we all begin life by experiencing the mother’s heartbeat...You can even have rhythm without sound - a deaf and blind man can experience the regular patterns in things...and books will have their own rhythms as you turn through the pages.”

The primacy of rhythm isn’t just a human phenomenon either - many different species show spontaneous rhythmic capabilities. California sea lions headbang to disco, Asian elephants sway to Gangnam Style, and biologists have established that Sulphur-crested cockatoos have 14 distinct dance moves (definitely more than I do). And watch what happens when you give an acoustic guitar to a capuchin monkey:

I’ve written elsewhere about how societies of the East and West tend to speak of their percussionists as a sort of ‘missing link’ between the civilized human world and the raw, unbridled physical expressiveness of the animal kingdom.

The stylizations of fictional drummers often reflect this - Animal from The Muppets, the strange sheep-like drummer in the Wine Gums advert, and of course the gorilla in the Cadbury commercial.

And us guitarists, despite being genetically human, are percussionists too. Almost all our music is rhythmic in nature, and virtually every genre uses a variety of non-resonant strums and strokes. So why not expand our primeval urges to the whole instrument? Below, we sample a few ways to get started with this.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

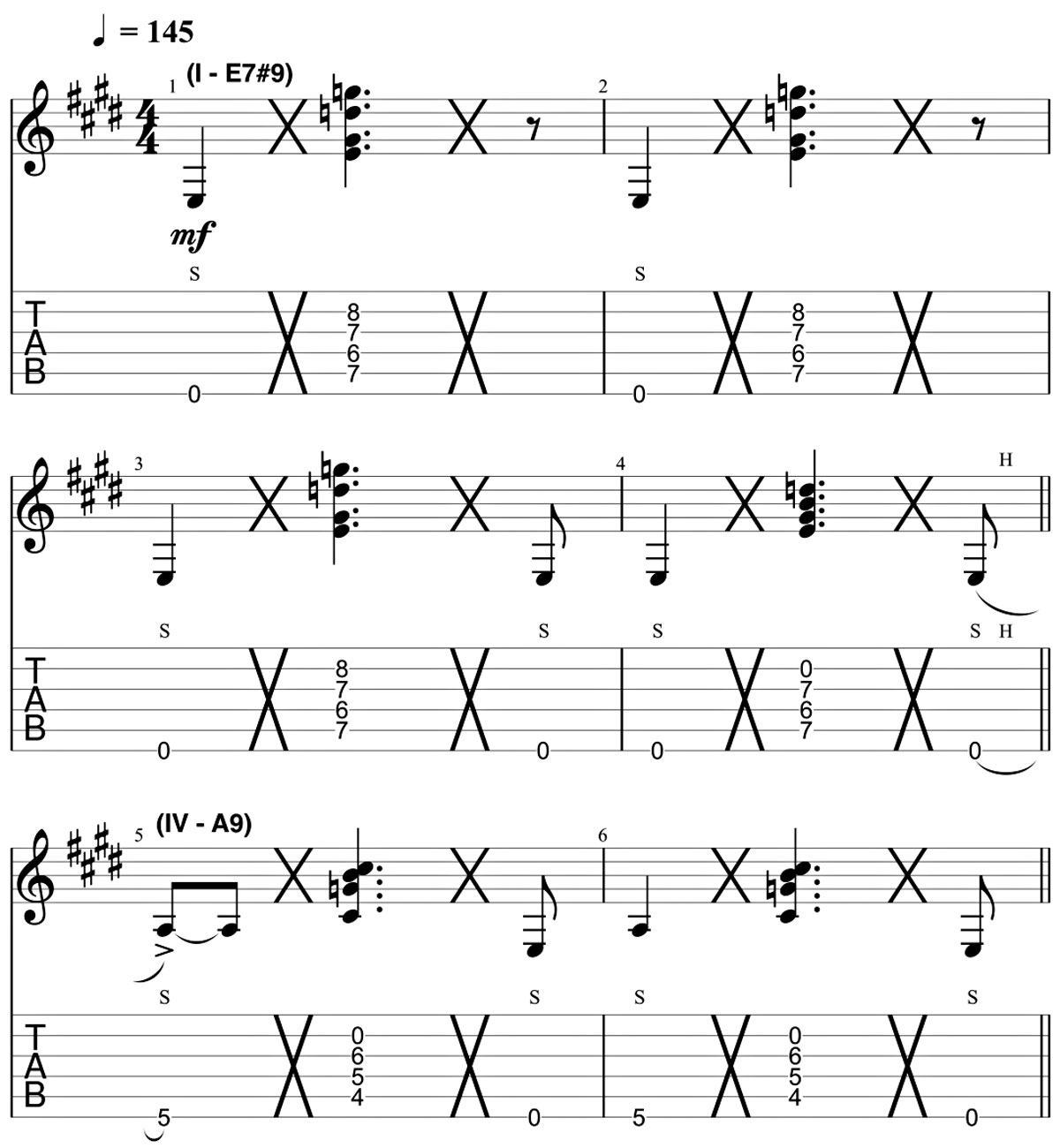

Exercise 1. Three-layered 12-bar blues

When incorporating percussive sounds, it can be useful to relate the tones of the guitar to a few common ‘drum types’ - low, resonant sounds are the kick, punchy mid-range textures are the snare, etc.

Once you know what sounds your guitar can produce, you can combine them to form kits. This helps you quickly build intuition for what to reach for - e.g. if, when jamming, you want a cymbal-type sound, your hands will be primed with a few different options.

For me, two of the most useful kits are the drum kit (kick/snare/hi-hat), and the backing band (drums/bass/chords). This exercise demonstrates how to apply the latter to a percussive 12-bar blues in E. Here, we set things up as follows:

- Bass: slap the 6th string firmly with the thumb

- Drums: tap just behind the bridge with ring & pinky fingers

- Chords: strum or slap the middle few strings with the index finger

Start by looping up the first chord, focusing on the quality of the sound for each movement, and think about how you need to move your picking hand index finger to maximise the harmonic strengths of each voicing. Getting the right overall balance of sounds is tricky, and requires a fair bit of practice.

You have to find your 6th string’s sweet spot for thumb slaps - places where resonance is even and strong, and maybe with a bit of controllable string buzz if you hit hard. It’s often closer to the bridge than for usual picking. (Bonus exercise: see how many weird and wonderful natural harmonics you can find by by slapping around just past the bridge side of the soundhole):

Try it at different tempos, and rejig the pattern, isolating and rearranging its elements as you go. Once you’ve mastered a few different shapes and grooves, you’ll have all the elements required to write your own. And as for all the exercises in this lesson, the golden rule is that you can get away with quite a bit of roughness and imperfection as long as you’re consistently nailing the rhythmic groove.

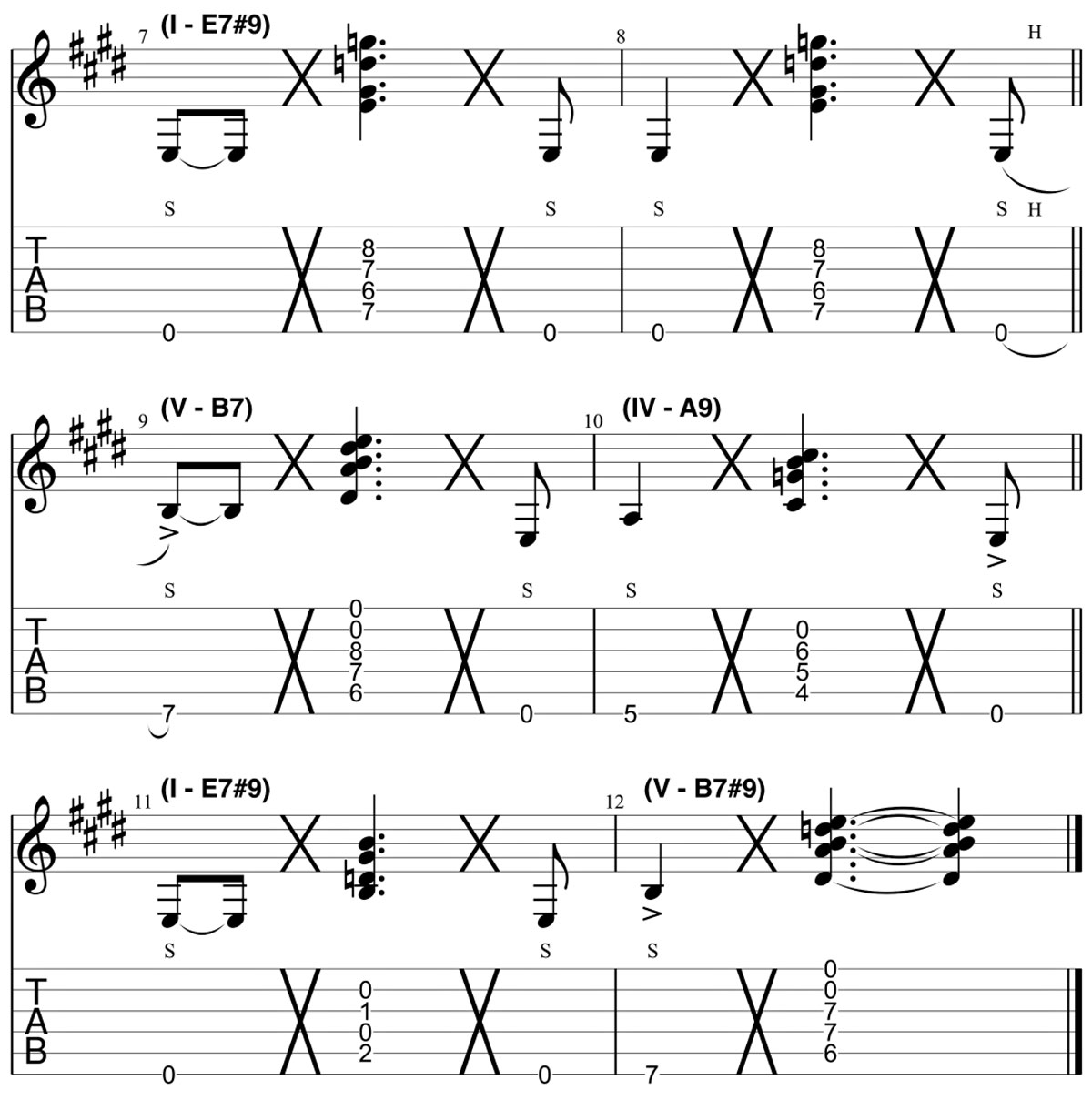

Exercise 2. Jazz swing and walking bass

Percussion is about hitting - the word derives from the Latin ‘percutere’, meaning ‘to strike forcibly’. But that isn’t the only way of producing sounds from the body. We can also slide across the surface to recreate various cymbal sounds.

Admittedly, this works better on some guitars than others (e.g. gloss surfaces often kill the slide), but is a lot of fun if you can coax some pleasing textures from yours. But before we begin, have a listen to some hard-swingin’ jazz for inspiration:

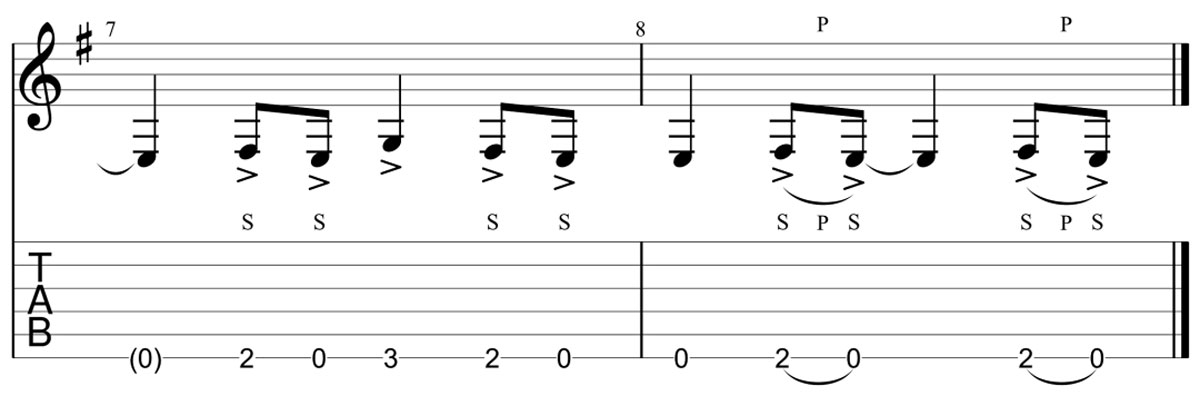

The following exercise explores some similarly jazzy swing rhythms, layering some ‘cymbal slides’ (played with the fingers) over a bassline loop (played with hammer-pulls on the 6th string).

The only way to learn to swing is by playing along with the masters, so put on some of your favorite jazz and settle into the rhythms. Nod along, or tap on your guitar, or your desk, or in your pockets while you’re out wandering - anything to get it in there.

The offbeat articulation is deceptively difficult to get right - swing, though borne of pure feel, reveals itself to be full of densely mathematical detail when subjected to academic analysis. Start slowly, focusing on getting the best actual sound textures you can - you can speed it up more quickly if you accurately nail down the movements first:

Exercise 3. Thumb-slapping independence

We can get percussive on the strings too. Rhythmic thumbing techniques are more prominent in the world of electric ‘slap bass’, with virtuosi such as Victor Wooten taking it to unprecedented modern heights. It has been around since at least the mid 60s - Larry Graham, bassist for Sly and the Family Stone and Graham Central Station, did perhaps more than anyone to popularize the style (although he calls it, perhaps more accurately, thumpin’ and pluckin’).

In his words, the innovation sprung from experiences performing live with his mother as a child: “My mum decided that we’re not going to have drums any more... that’s when I started thumping the strings with my thumb, to make up for not having that bass drum, and plucking the strings with my finger, to make up for not having that backbeat on the snare drum - so it’s kind of playing the drums on the bass”.

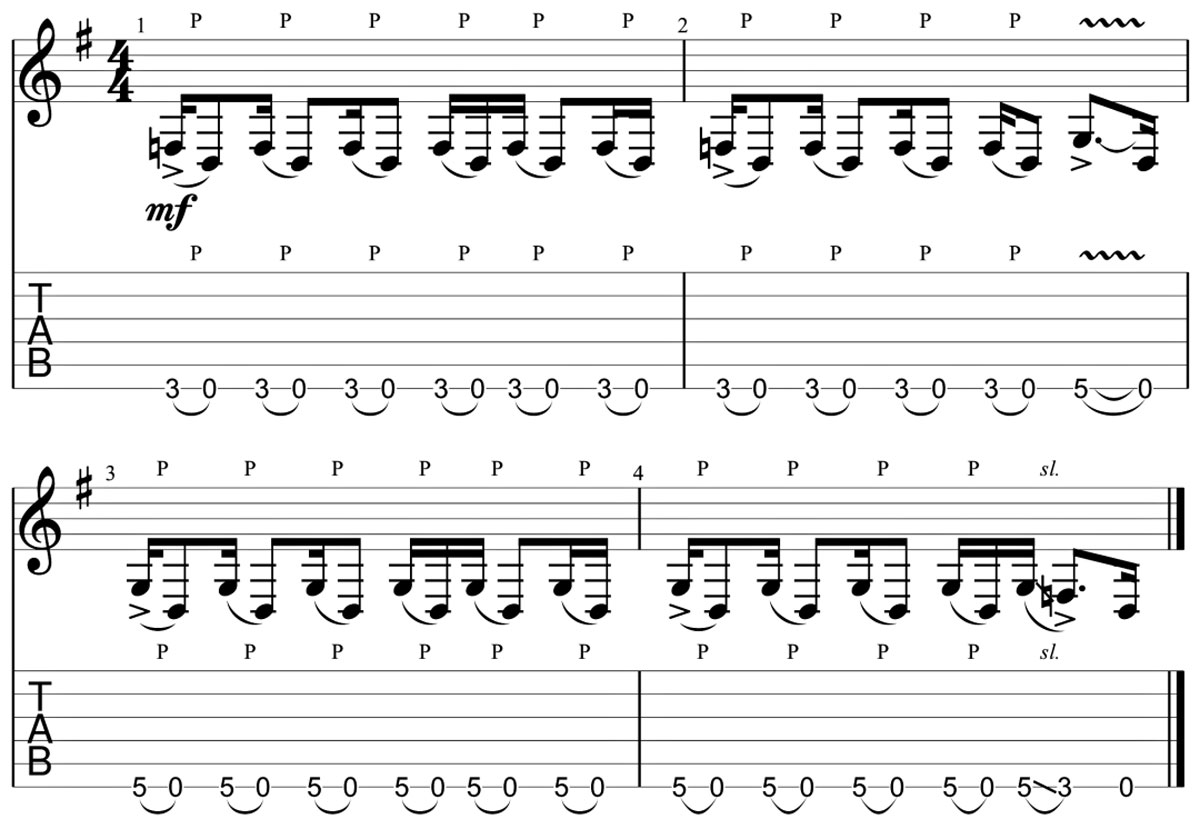

But unlike the standard electric bass, the guitar has an added capability here too - we can combine slap-style hammer-pull patterns with percussive body tones. This can create the craved ‘full rhythm section’ sound that is emblematic to much of the most exciting solo acoustic guitar music.

In this exercise, we have a go at the ‘full rhythm section’. Go to the furthest-away ‘corner’ of the body - an area that offers deep, strong bass tones as well as a snare-like ‘clack’. Again, get really familiar with the pattern as it is - some of the layered syncopations don’t easily slot into place at first - and then use it to create your own variants and grooves:

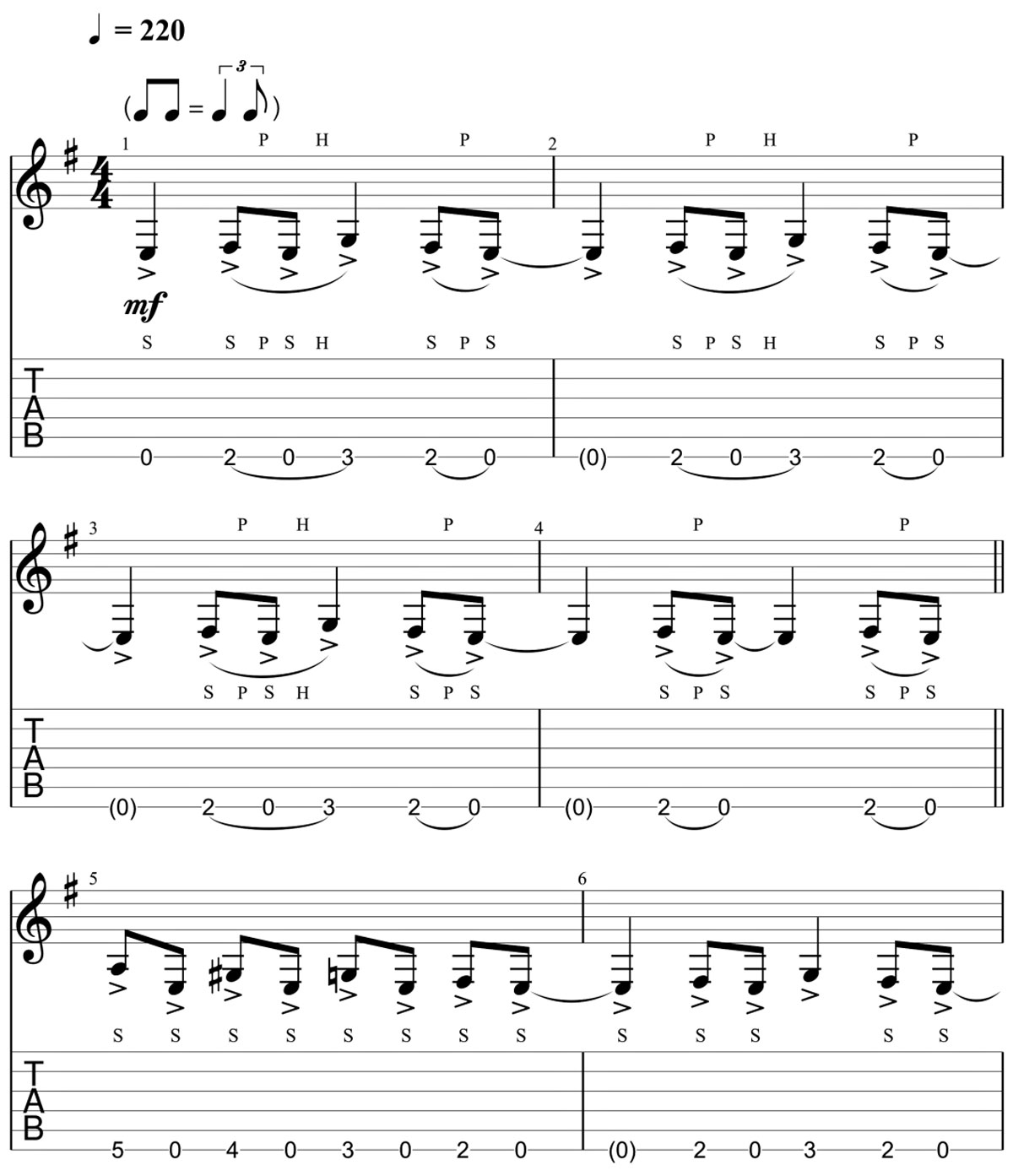

Exercise 4. Melodic percussion lines

The lead line of a piece doesn’t always have to be the melody. We can also use percussive sequences as alternate melodic voices - something done in almost every genre to varying degrees. Jazzers will be familiar with the idea of trading fours, where horn melodies alternate with unaccompanied drum fills, and fans of jungle, DnB, and other heavy electronic styles are used to percussion occupying the centre of the music.

Similar concepts are also prevalent in Indian classical music. Rhythmic imagination is vital to all of India’s classical traditions, with the tabla (in the North) and mridangam (in the South) playing prominent roles.

Performances are often just duets, leaving the drummer in an influential but exposed role. Musicians use various forms of interplay to explore the space, combining the spontaneous with the mathematical and architectural.

One such trick is the sawal-jawab - or ‘question-and-answer’ section of North Indian Hindustani music, where the lead melodic musician throws out phrases for the tabla player to copy or respond to. Watch bansuri bamboo flute master Pandit Rupak Kulkarni and young tabla maestro Ojas Adhiya in action at Darbar Festival 2018 in London. India’s classical arts may be devotional, spiritual endeavors, but they are often light-hearted and playful too:

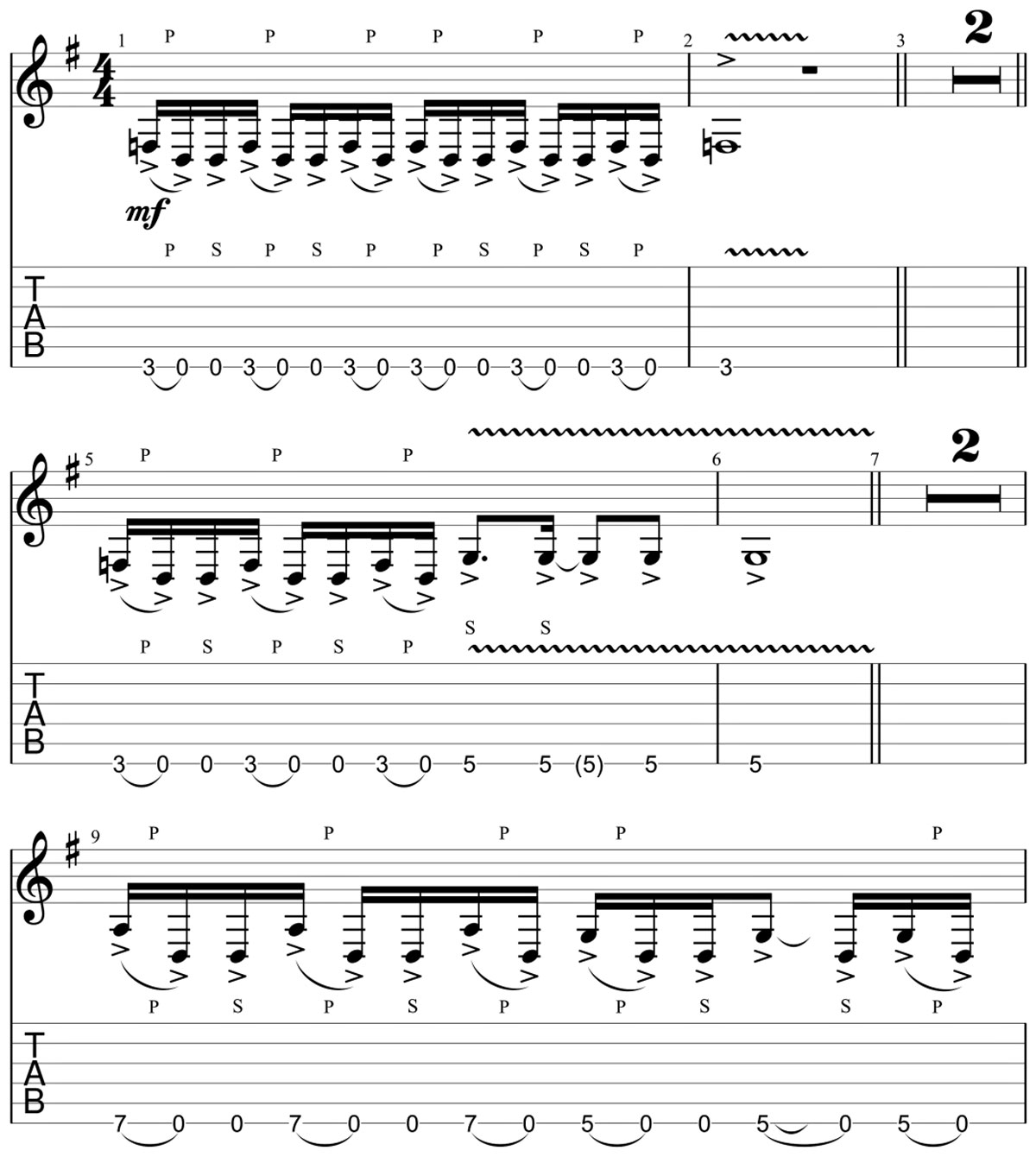

Our final exercise is a simplified take on the Hindustani sawal-jawab, recreating some tabla-style movements on the top of the body. This part of the instrument is less resonant, and consequently there is less variety between our drum sounds by default. Here, we separate out melody and rhythm, and use our (formerly) fretting hand to add a low kick sound on the strings. Try out something like this, and find your own patterns and combinations rather than copying mine exactly:

- Bassline: thumb slaps and hammer-pulls on the 6th string

- Snare, hi-hat: finger/thumb slaps either side of the guitar’s top ‘corner’

- Kick: palm slap the right hand onto the strings near the bridge, while muting them with the same palm

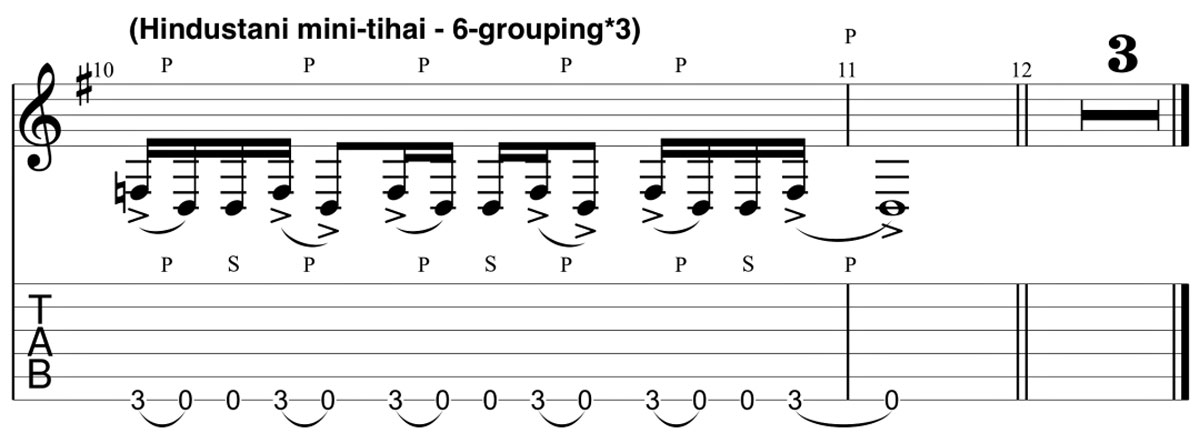

Note the quick rhythmic resolution pattern at the end. Known as a ‘tihai’ (literally meaning ‘three times’) it involves thrice-repeats a rhythmic phrase so that the final stroke falls on the first beat of the underlying cycle. (Read my full article on the tihai here, exploring why patterns of three have such a distinctive power to tell concise ‘stories’ in music, art, and literature. Indian rhythm is seriously fascinating!)

Learn from the masters: Jon Gomm's full drum kit

Fingerstyle master Jon Gomm is a man of many talents. He grew up learning folk, blues, and rock, and turned down a place at Oxford University to devote himself to the guitar, instead eking out a living playing jazz, blues, and country in small clubs.

Today he is renowned worldwide for his tastefully virtuosic acoustic approach, building on the acoustic innovations of the great Michael Hedges to push the outer limits of multilayered guitar playing. Watch his superb breakdown of how to recreate the sounds of the drum kit on the guitar:

His approach is more powerful and versatile than ours, but it is also - evidently - much harder. We can get there with enough practice, but all have to start somewhere (although it seems that Jon may have started somewhere quite different to the rest of us...I spotted him amongst the YouTube commenters on the capuchin monkey video above, saying: ‘rare footage of me as an infant’).

The adult - and outwardly very human - Jon Gomm rejects the idea of corporate compromise with labels, playing the music he wants to in smaller venues. He teaches widely, and engages with fans directly (I remember having a great post-show chat with him as a teenager).

You may well have seen his astonishing Passionflower already - also check out his excellent instructional series, Essential Percussive Guitar Riffs.

Percussive playing may allow us to inject some primal strength into our music, but is a sophisticated art to master. We must feed unfamiliar patterns to our minds and bodies, adding new types of sound to our improvisatory palette and drawing on a broader range of muscle groups than we normally would.

The basic mechanics of fingerpicking and tapping introduce other complexities too - e.g. with a plectrum we don’t really have to consider the ‘natural harmonics zones’ of the strings, but when thumb-slapping then we do.

And in general, fingerpicking and body tapping motions are more ‘3-D’ than simple alternate picking, at least in terms of what you have to worry about. And spare a thought for the soundman when playing anything like this live...(always soundcheck properly!).

This is a particularly fun area in which to ‘loosen up’ your approach to the guitar, on the levels of the musical, physical, and psychological. As ever, experiment in all directions - mute the open string tones with an elastic band, attach paperclips someplace, or stick on a tin lid like Mr. Guitaro 5000 so you can be better heard while busking on the NYC subway.

Further listening and learning

No rundown of percussive acoustic guitar would be complete without mention of the Candyrat label. Their YouTube channel has amassed hundreds of millions of views, creating something of a new global market and launching the careers of virtuosi such as Andy McKee, Antoine Dufour, Ewan Dobson, and Mike Dawes.

Also check out Erik Mongrain - his AirTap went viral, and seeing him perform a decade or so ago genuinely raised the bar for how precise I thought a guitarist could be throughout a whole live set. His compositional sense is far beyond most of his peers too...amazing musician. And see how Adam Ben Ezra does similar things on a double bass, and Kris Bowers too while playing Kendrick Lamar on a piano...

Read more about the surprising science of animal rhythm - a topic any improviser can learn a lot from - in this NPR article: “A psychology grad student at Harvard...amassed 5,000 video clips of different animals (very different - horses, cats, albatrosses, chimps, orangutans...), all purportedly dancing...

After eliminating nonmusical, autonomic and overly trained contestants, she narrowed the field to 39 animals who seemed to be spontaneously moving to a beat. Twenty-nine of them were parrots. The rest... were elephants. Asian elephants.”

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.