If you're playing in a blues trio, you have an awful lot of freedom with your guitar parts – here's how to make the most of being the only guitar player in the band

These major-sounding blues ideas are ideal for those situations where you've only got the drummer and bass player for company

Whatever we’re playing or soloing on, it’s always essential to keep the basic chord harmony in mind. However, in a trio format of drums, bass and guitar this is especially important because there is nowhere to hide. I’m specifically thinking of John Mayer, Hendrix and SRV here.

The trio format gives you an awful lot of freedom to play around with different ideas, such as switching between major and minor, superimposing different triads over whatever chord the bass is implying (more on this in a moment), or leading the way with dynamics in terms of volume or rhythmic complexity.

Overall, I would consider this to be a major‑sounding 12-bar blues. Listening through these ideas, you’ll notice that there are times when the bassline uses the major 3rd along with the root and 5th. To be more specific, you’ll hear E (root), major 3rd (G#) and 5th (B) featuring in the first four bars, followed closely by a similar pattern transposed to A for the IV chord (root is A, major 3rd is C#, 5th is E).

Sometimes, the bass doesn’t outline the whole chord but just uses the root and 5th. In theory, this could free us to play minor pentatonic patterns, or even change the feel to a minor one for those chords. But given the strong major-context setup in the first few bars, this isn’t my recommendation…

However, it is my intention to demonstrate how straddling the gap between the minor and major 3rd with slides, trills and bends can enable us to use minor pentatonic shapes as a basis. And I’ve done this occasionally in this lesson’s examples below, along with plenty of major pentatonics and partial chords.

This is a fascinating area to explore and these ideas only scratch the surface, but I hope they will open up some new areas for you to consider.

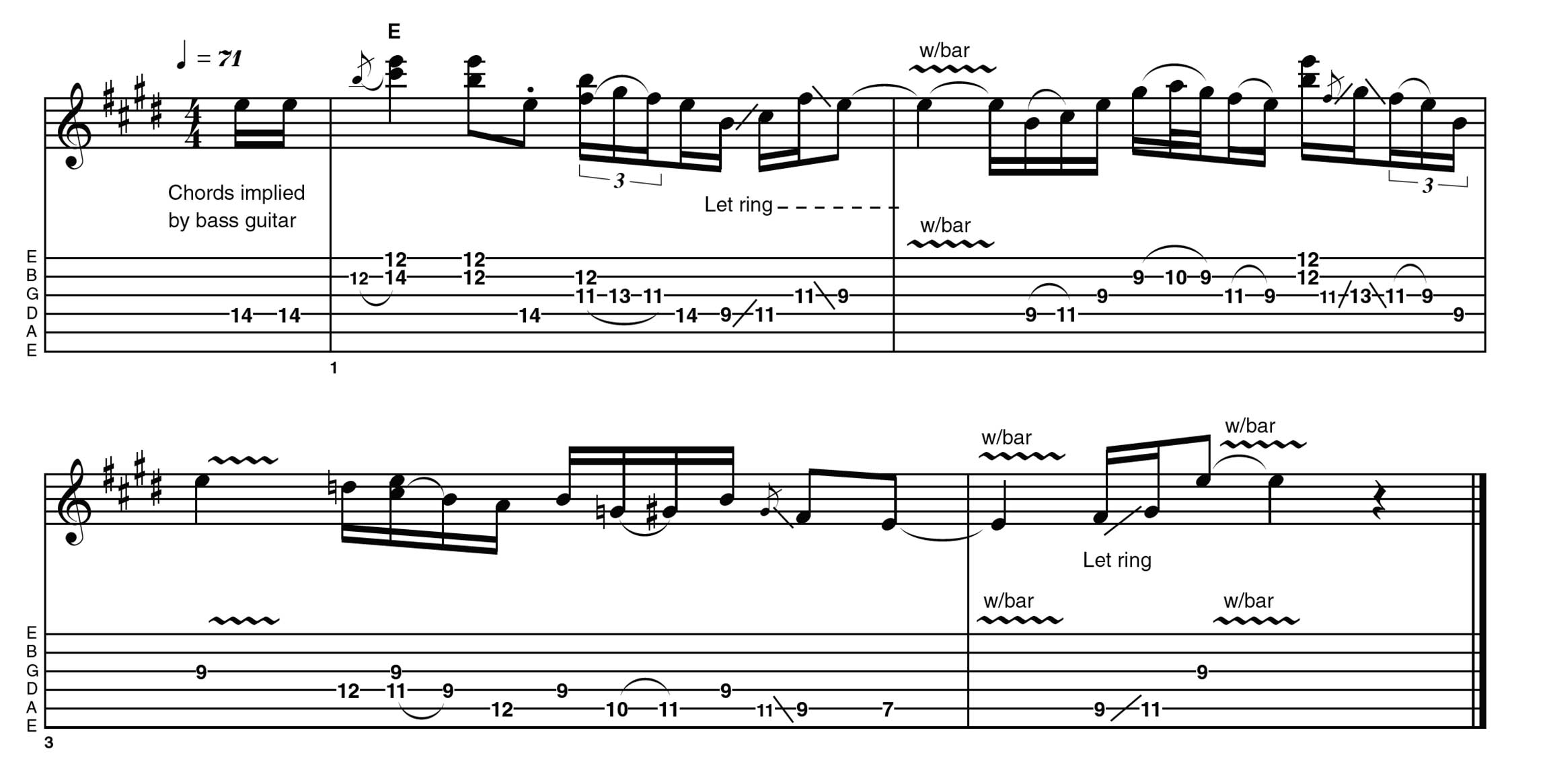

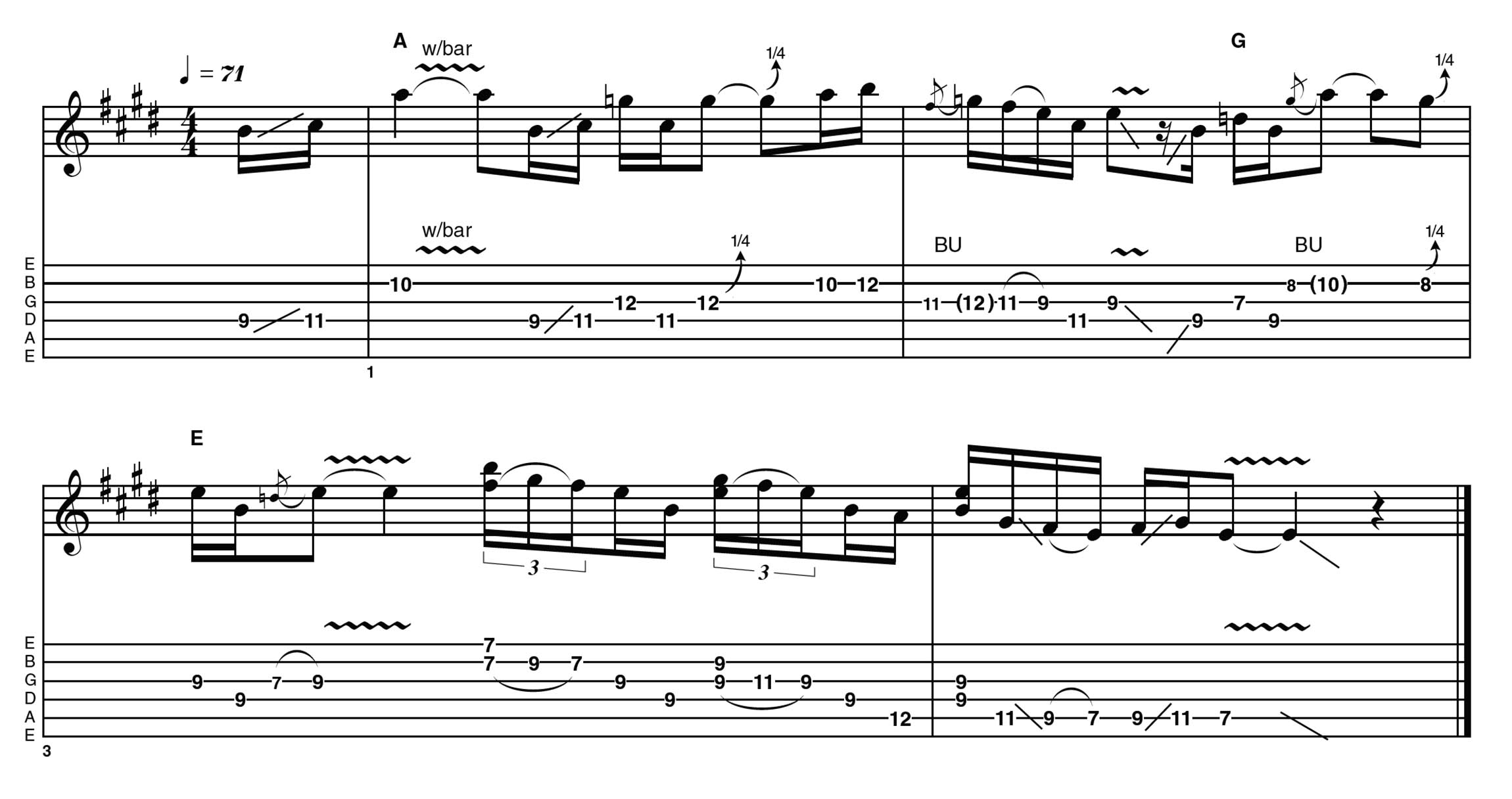

Example 1

I view this example as a hybrid of the major pentatonic, using shapes 1 then 5 and combining some doublestops, where I’m playing two notes of the scale at once by flattening my fretting hand’s fingers to form a partial barre.

There’s a brief hammer onto A in bar 2 to give a ‘sus4’ embellishment from outside the pentatonic shape, followed shortly afterwards by a D natural for an E7 feel. It’s not necessary to always be conscious of this level of detail in real-time, but remember these shapes.

Example 2

The implied chords here are A major, G5 and E major. I’m seeing the first two notes as part of an A major chord using the CAGED patterns – a full A major chord up here is the same shape as a C major chord down in open position. Blink and you’ll miss it, but this gives a great starting point.

After a play around with A7 (by including a few G naturals), I’m using the same CAGED approach for the G chord by moving two frets lower. The final doublestops are culled from the E major pentatonic, but you’ll notice some sneaky CAGED E major inversions if you look carefully.

Example 3

Moving to the V chord (B) then the IV (A) and a brief shift to G, we head for the ‘home’ chord of E major. I’ve started with the shape 1 E minor pentatonic – not the first scale we might choose, but it adds a nice bluesy touch.

Towards the end of bar 2, this switches back to a major approach with those doublestops. Note that I’m shifting down two frets to use a very similar pattern as a nod to the brief G chord. A short minor/major blues lick then lands at the final B7(#9) chord.

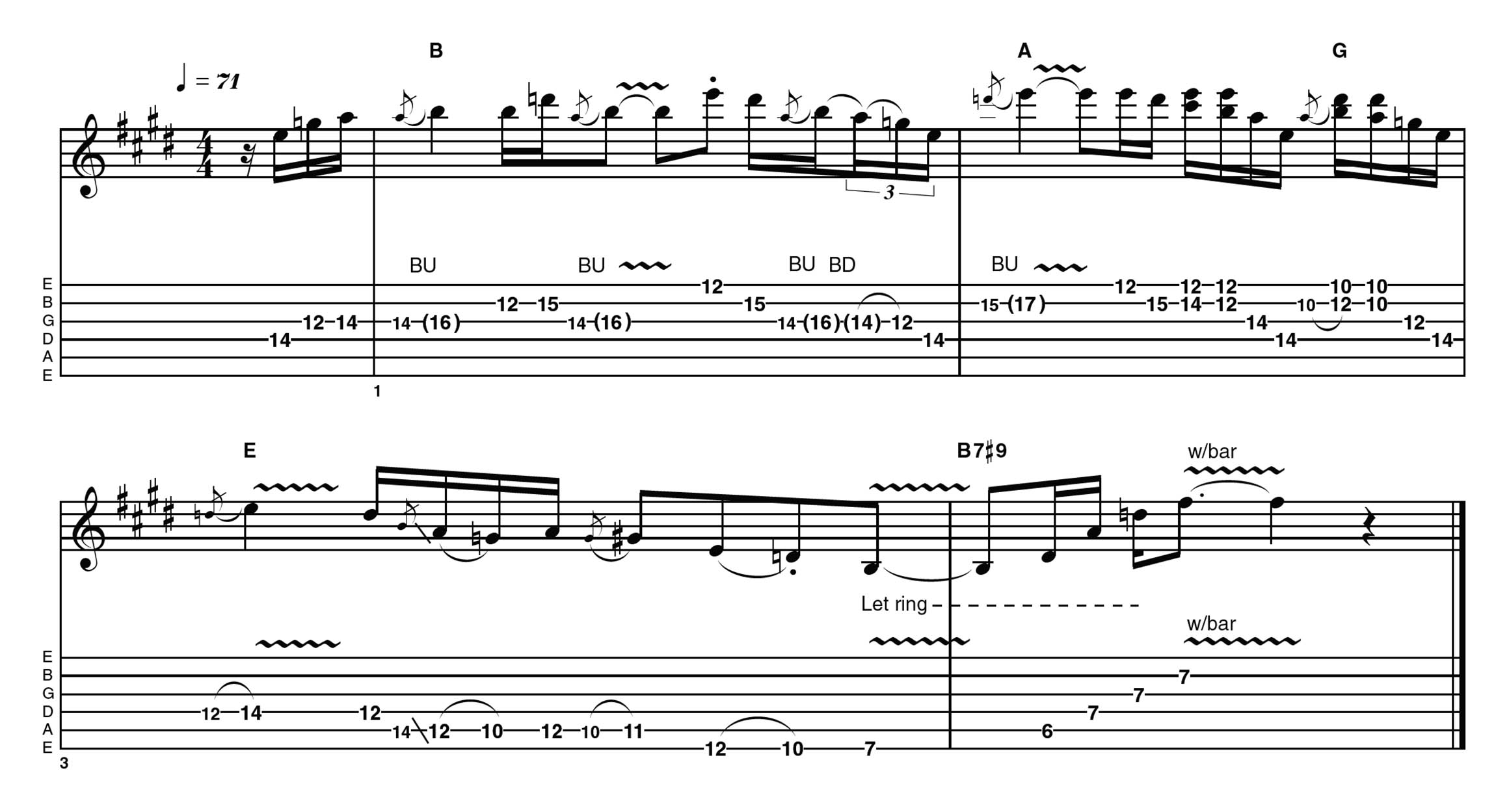

Example 4

An alternate take on the first lick, or the beginning of a second time round if you prefer, this starts strong with an open low E. We then work our way up the major pentatonic but add a bit of ambiguity with the bends in bars 2 and 3.

These bring in the 7th (D) and minor 3rd (G), albeit fleetingly. You’ll often find these patterns can be absorbed into your repertoire without always having to be hyper-aware of the chord tones, but that is a good place to aim for!

Hear it here

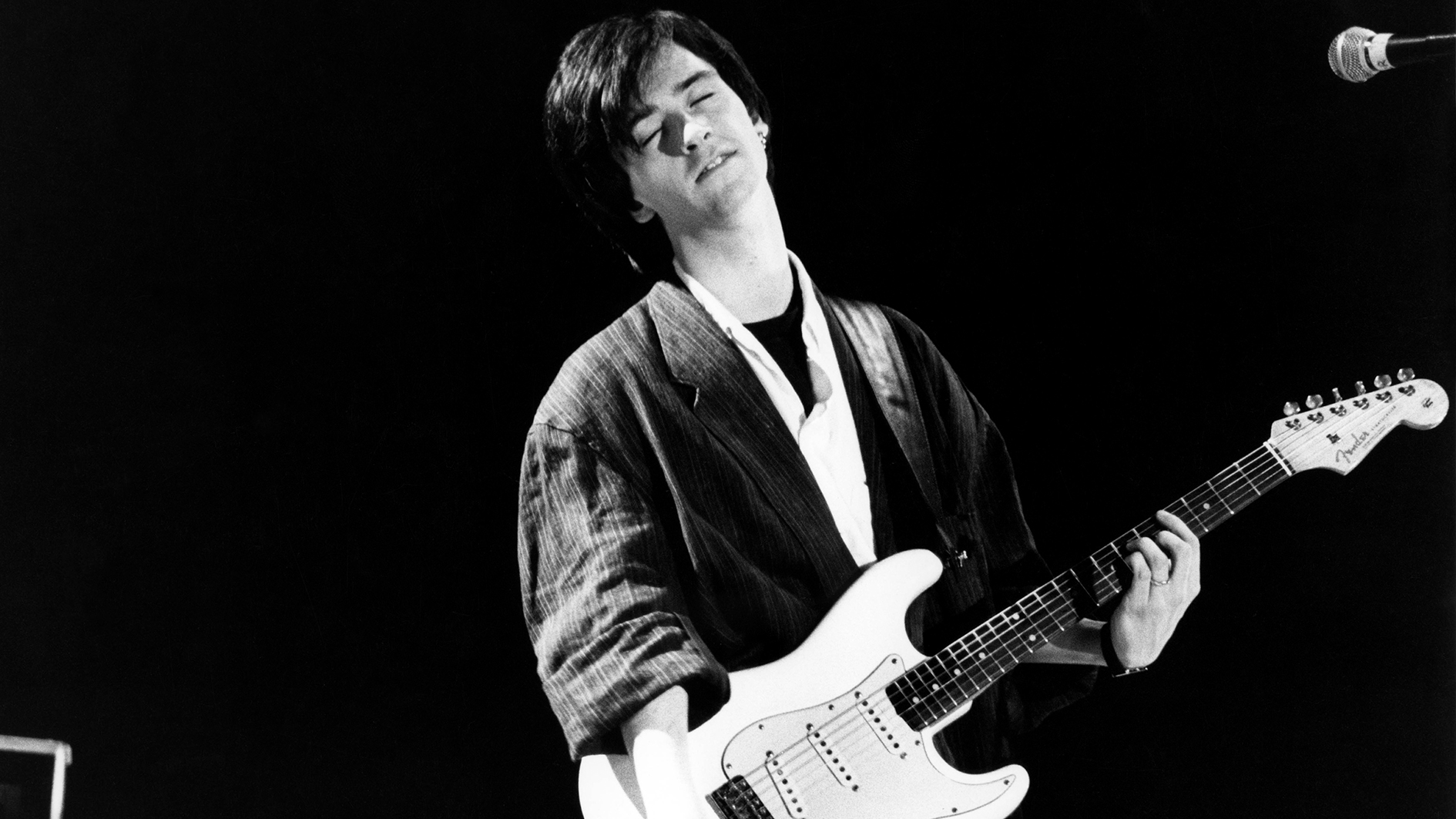

John Mayer – Where the Light Is (Live in Los Angeles)

John was already in the major league by the time this album was released in 2008, but anyone who had lingering doubts about his authenticity would be swayed by the masterful playing here. He’s right in the area we’re looking at around halfway through this version of Gravity.

There is also some nice doublestop work in Slow Dancing in a Burning Room, though at least some of this is played by the fabulous Robbie McIntosh. Also check out Bold as Love throughout.

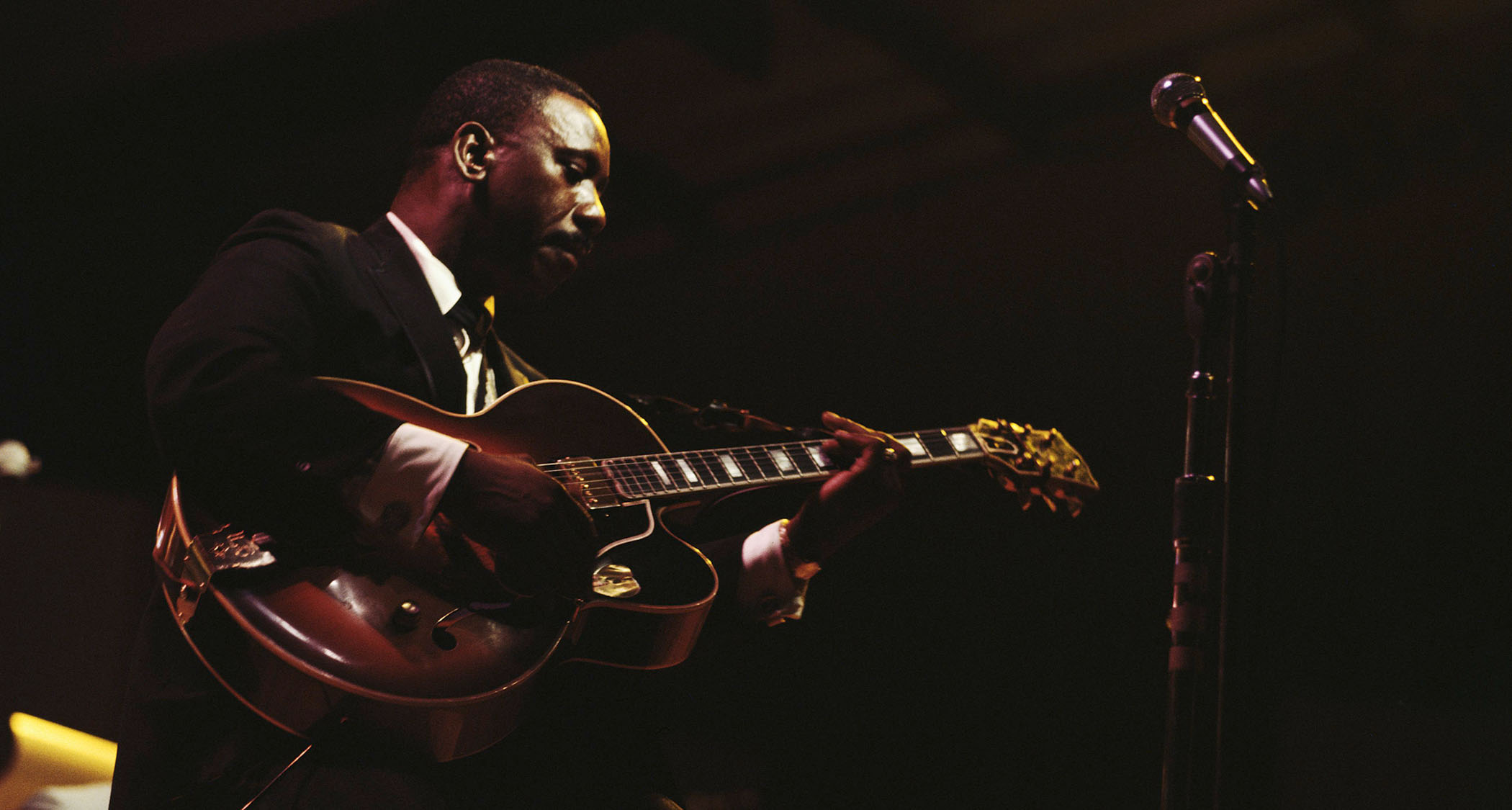

Stevie Ray Vaughan – Texas Flood

Recorded virtually live over three days in Los Angeles, Stevie is on fine form throughout, filling harmonic and rhythmic gaps with style. The title track is a great place to start, followed by Pride and Joy, where he manages to sound like two guitars playing the rhythm part!

Finally, check out Lenny. This remains one of his finest recorded performances, often cited in these pages and for good reason: it is a masterclass in this style of playing.

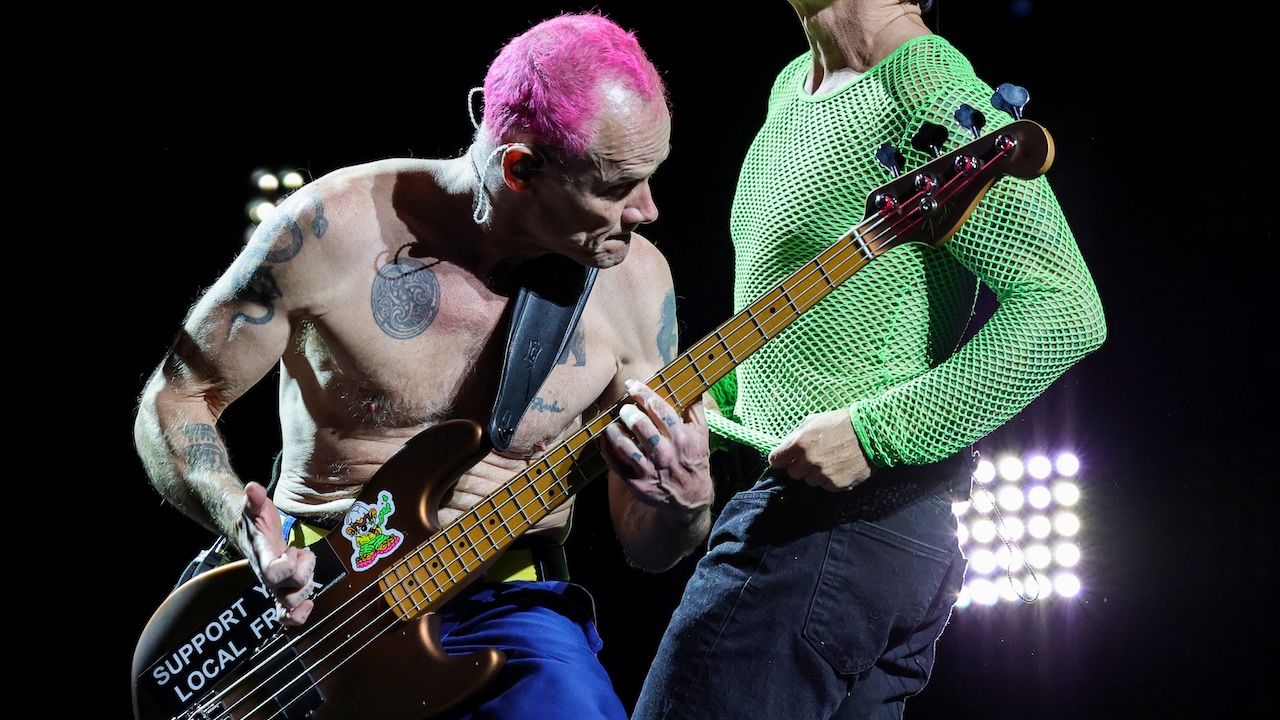

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Axis: Bold as Love

Obviously, there is much to be gained from listening to virtually all of Jimi’s work, but of particular relevance here are the title track, Castles Made of Sand and Little Wing, where Jimi blurs the lines between rhythm and lead, as well as between CAGED chord shapes and pentatonic patterns.

Jimi was a major inspiration for the other two players cited here and really knew how to fill out the sound of a trio, though there are also some overdubs on these studio versions.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.