How to combine rhythm and lead in a blues guitar solo

Add variety to your blues playing by bringing the two disciplines together in the vein of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix

The distinction between ‘lead’ and ‘rhythm’ guitar has long been a very blurred line. In fact, guitarists such as Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan have managed to pretty much obliterate that line on many occasions.

Having the ability to bridge the gap between those two ostensibly different worlds can really open up the fretboard in a way that remains useful even when staying within strict rhythm or lead boundaries.

For this piece, I’ve used a harmonically sparse but relatively busy bass and drums backing. This allows me to sit back on a more chordal approach or venture into single-note territory with relative freedom, including whether I want to emphasise a major or minor feel, if you check out the whole solo.

As an overall dynamic, I’ve tried to set up an expectation of E7-A7-B7, with a B7#9 being very hard to resist at the turnaround – so I didn’t!

Initially using a mixture of doublestops, chord inversions and pentatonic shapes, I then move further into single-note territory as the piece goes on, coming back to state a full chord or a doublestop phrase here and there.

This is partly about balancing things to avoid sounding sparse, but equally where convenient shapes and licks present themselves. It’s always a good idea to have some ‘stock’ licks to work from – and to keep expanding that resource. By the last few bars, I’m mostly playing single notes, though these lines could be said to contribute to the perceived harmonic content to an extent.

If I had continued for another round, it might have been nice to drop down to some sparse chords and build up again, maybe using some more rhythmic patterns and space. Why not take these ideas as a template and use the backing track to develop further? Hope you enjoy and see you next time!

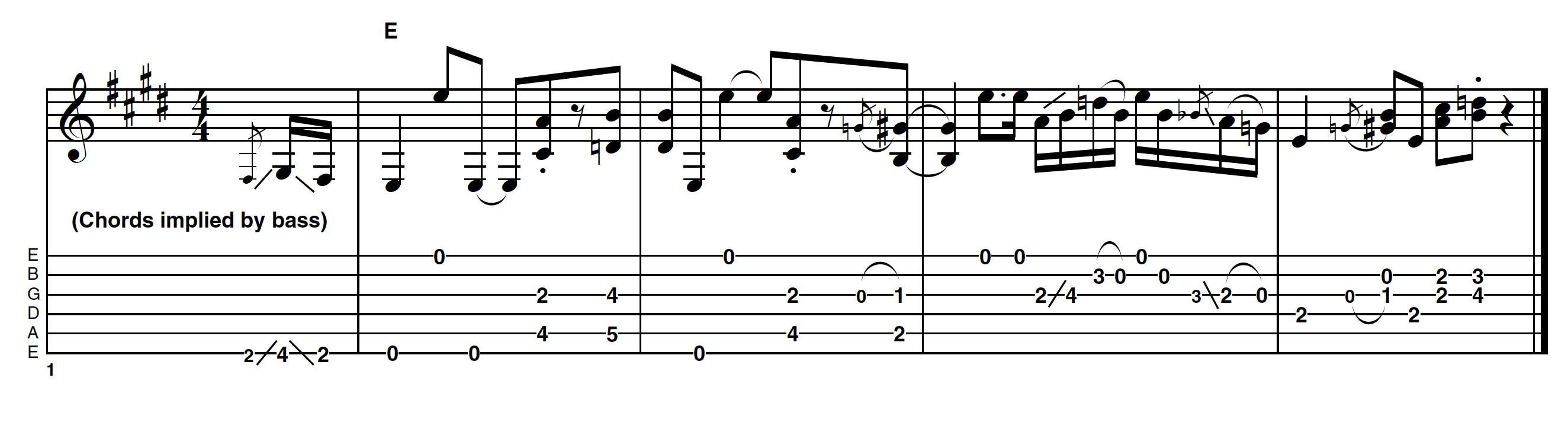

Example 1

Beginning with some classic ‘blues’ doublestops, mixed with some ringing open-position shape 1 pentatonic, this idea is about setting the stage and establishing a context.

Even the least musically knowledgeable listener will appreciate being given a context, and in these early bars of the piece it might be best to ‘keep your powder dry’, until some collective momentum has been gathered! I’m trying to demonstrate several ideas here, but why not play very sparsely and see how that feels, too?

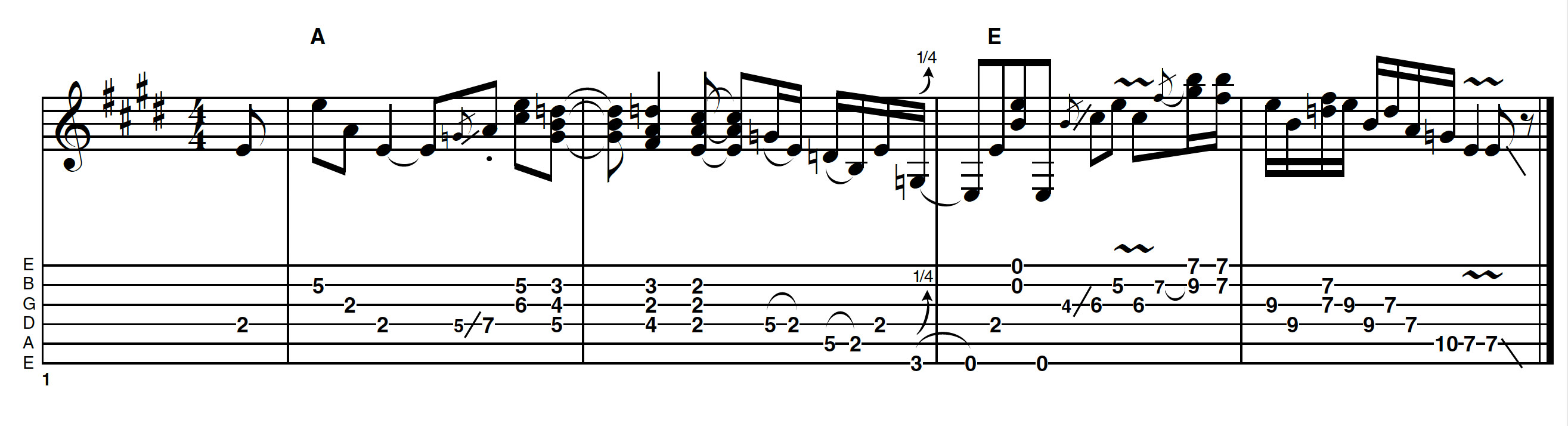

Example 2

In this next section, we change to the IV chord (A), where I’ve taken the opportunity to superimpose some descending triads (A, G and D) on the second, third and fourth strings.

You don’t need to be a chord theory expert to do this: try transposing this idea and these shapes over the E and B chords, too.

Under the cover of ringing open strings, I then shift up to around the 7th to 9th frets for some doublestops and a little run based around shape 4 of the E minor pentatonic.

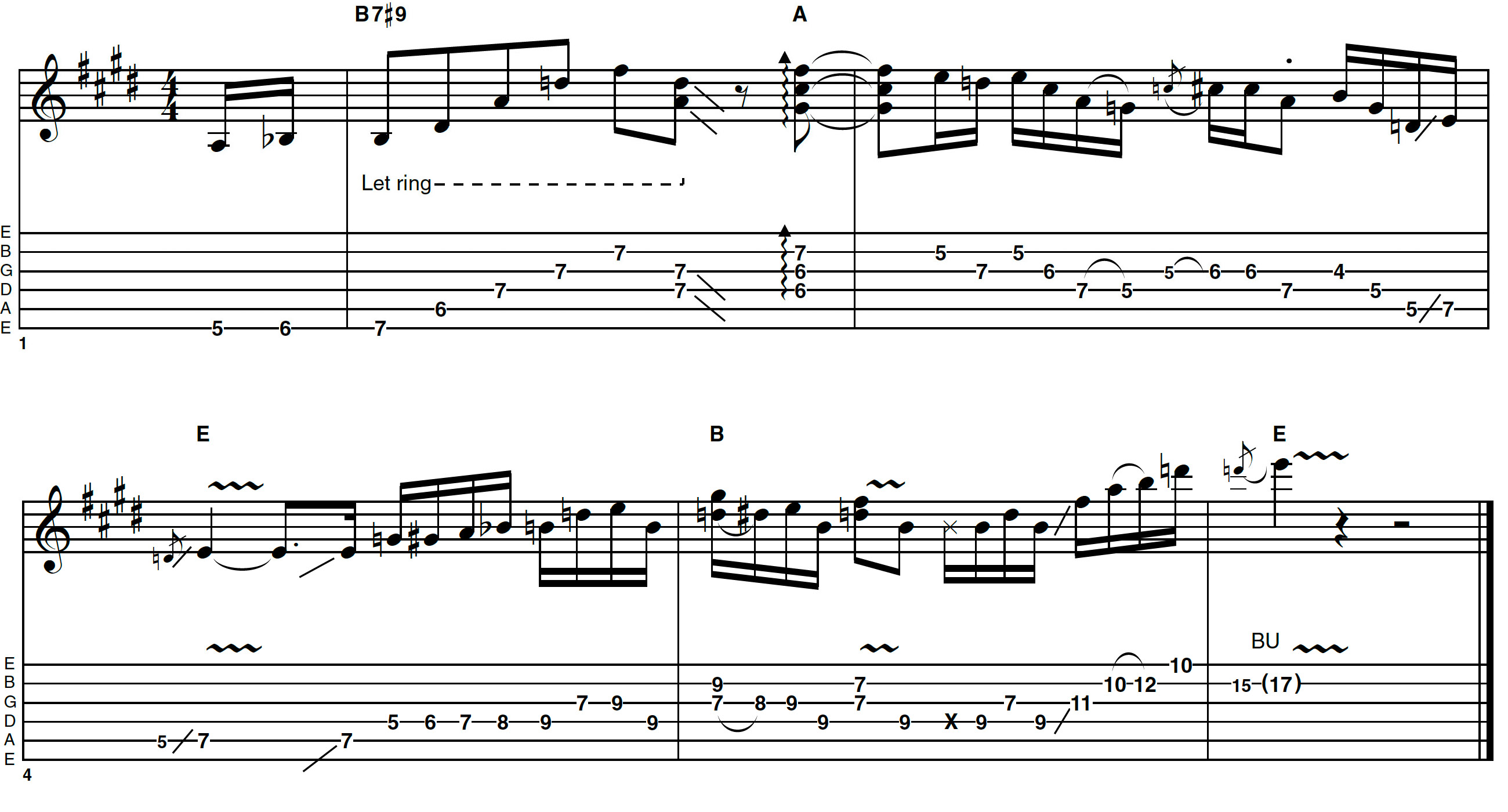

Example 3

I’ve chosen to underline this first statement of the V (B) changing back to IV (A) with a jazzy B7#9 leading to an A13 then picking out some of the chord tones from A major and G major.

To do this, I’m simply referencing the barre chords that live around the 5th then 3rd frets – camouflaged by the fact that I’m incorporating these notes into a pentatonic lick that then chromatically leads up to a fragmented B minor (trilling to major) chord and a horizontal grab for a high E to begin the next section!

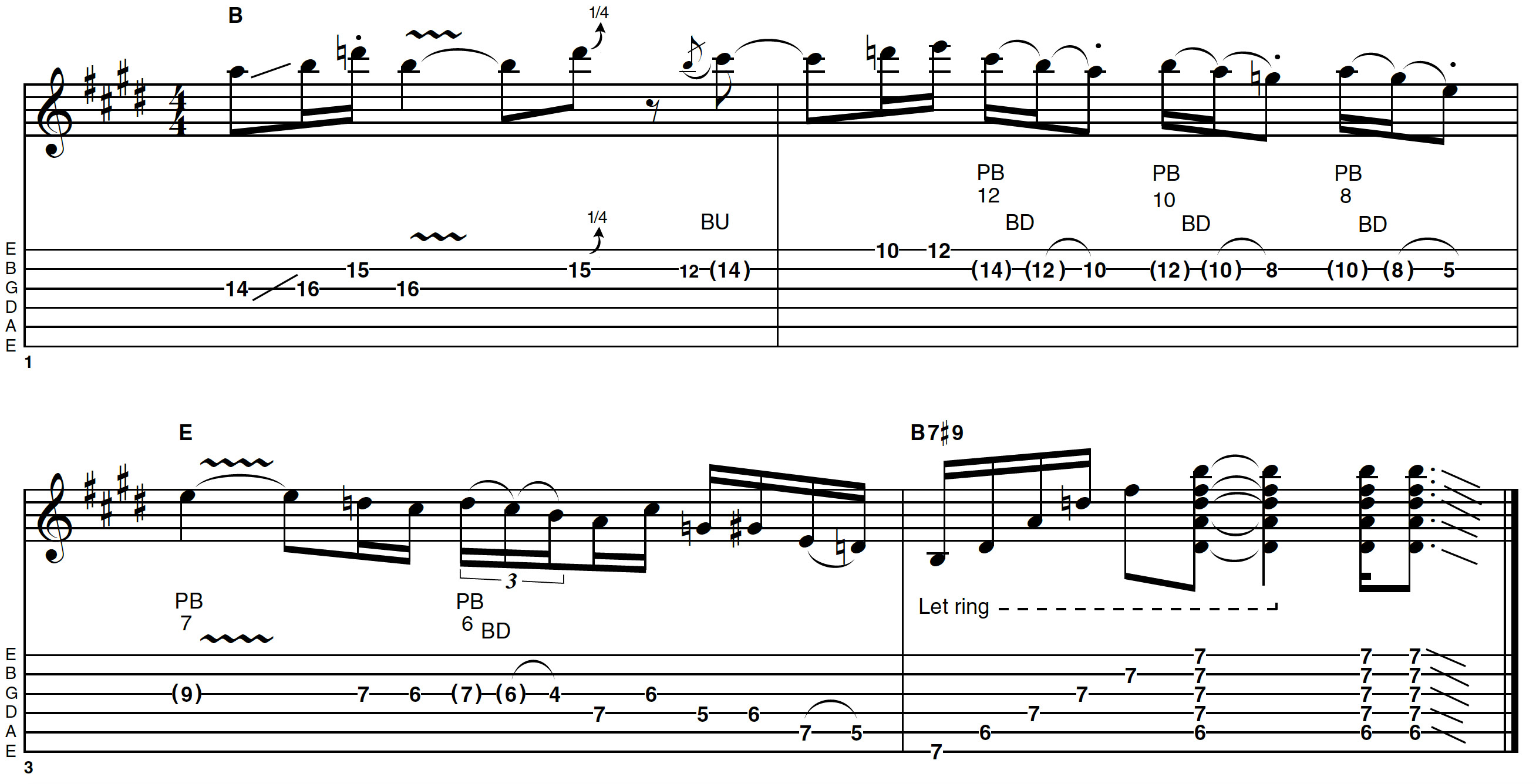

Example 4

Skipping to the final section, I’ve used the same string-bending idea as a repeated descending phrase over the implied A and G chords, before sticking around the shape 3 area of the E minor pentatonic (though I do incorporate a G# near the end of bar 3).

This leads very comfortably to another B7#9 (I couldn’t resist!) to finish. B minor pentatonic would also work well here, but I’m not sure it’d have the same impact – certainly worth bearing in mind for a longer solo, though.

Hear it here

Jimi Hendrix – Axis: Bold As Love

Any of the tracks here are recommended – not just for the specific licks and chords but also for Jimi’s overall approach as the main harmonic instrument in this three-piece format with a minimum of overdubs. The title track, while featuring a few overdubs later on, is a particularly great demonstration of this. Little Wing is worth revisiting, while Wait Until Tomorrow is a masterclass in creating harmonic and rhythmic interest.

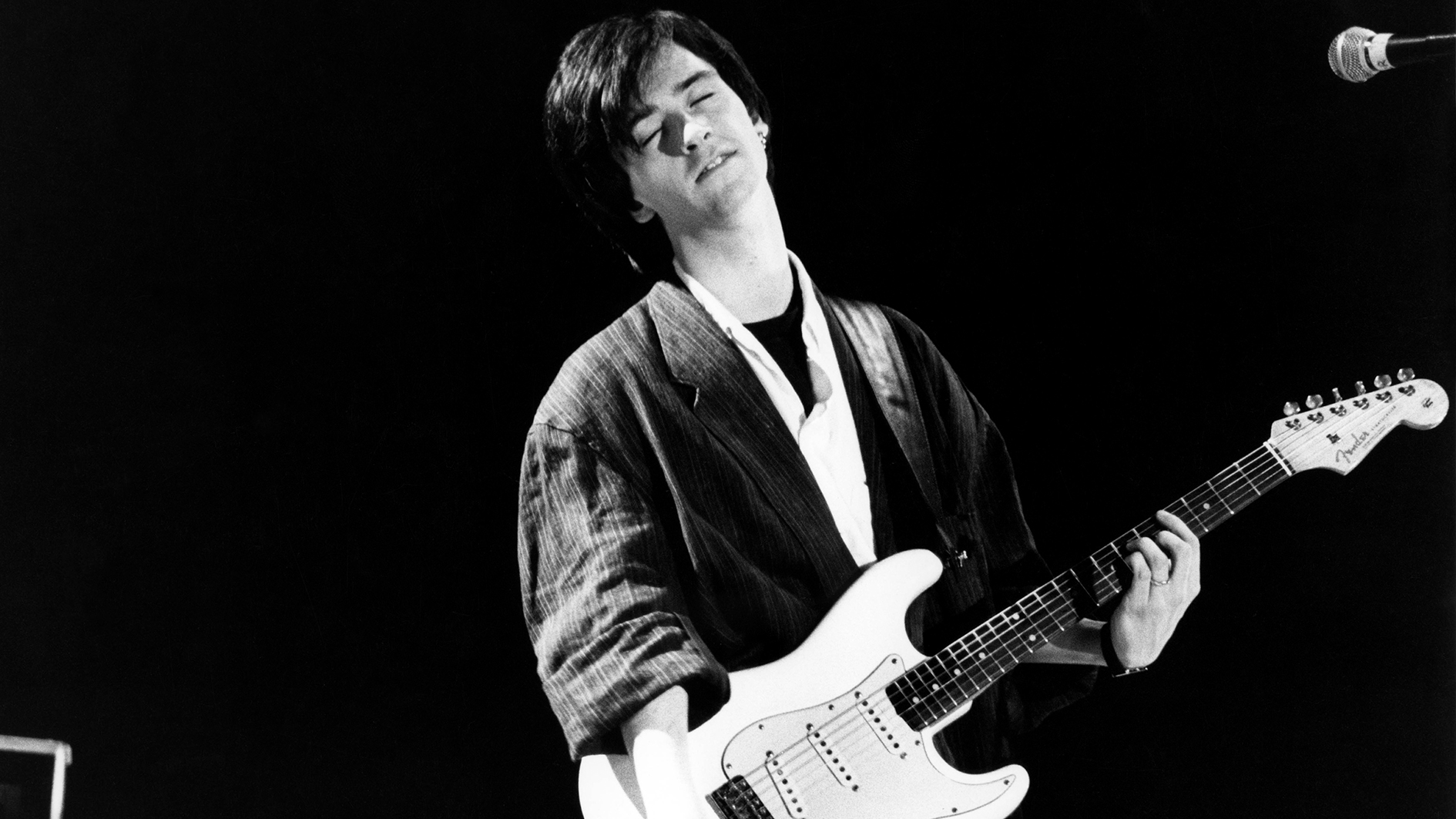

Stevie Ray Vaughan – Live at Montreux (1982 & 1985)

The first eight tracks, recorded in 1982, capture SRV at the moment he came to the attention of David Bowie and Jackson Browne. All the tracks give useful ideas, but going chronologically, starting with Hide Away and Texas Flood then skipping to 1985 with Couldn’t Stand The Weather, these showcase a mixture of rhythm and lead, which at times fills the space of two guitars but could also maintain interest with comparatively simple, sparse lines.

Matt Schofield – Heads, Tails & Aces

Though Matt has the luxury of keyboards to fill any harmonic gaps here, there is definitely a lot to be gained by checking out his tone and phrasing in these songs, particularly on the minor blues of War We Wage, the slow blues of Lay It Down, and the harmonically savvy phrasing of I Told Ya. Matt also manages to get piercing phrases through the Hammond organ accompaniment without any harshness – an achievement in itself!

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)