He’s the fearless, Strat-wielding counterpart to icons like Pat Metheny, John Scofield and Allan Holdsworth – and Wayne Krantz forged a raw, rhythmic approach to fusion guitar

A lesson inspired by the jazz great that will help the advanced players out there take their improv chops to the next level

Although he has been associated with the New York jazz and fusion scene since the 1990s, Wayne Krantz is originally from Corvallis, Oregon where he was born on 26th July, 1956.

Krantz took up the guitar at age 14 inspired by The Beatles and was later drawn to progressive rock bands, particularly Jethro Tull and Chicago. Krantz attended Berklee Music School and has described himself as a Pat Metheny-style player during this period.

Following his graduation from Berklee, Krantz eventually found his way to the signature gritty ‘edge-of-breakup’ Stratocaster sound which can be heard on solo albums from Signals in 1990, onwards.

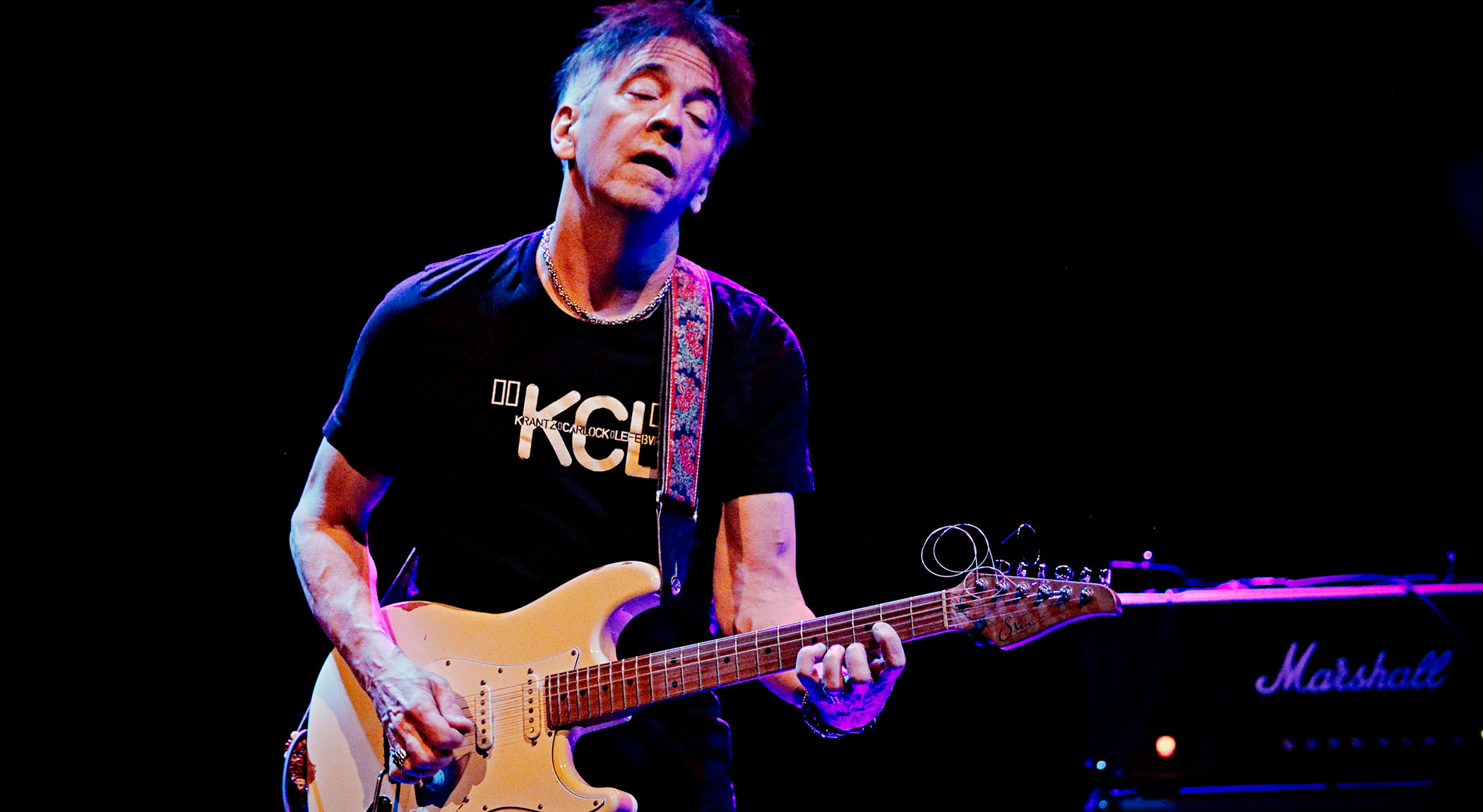

Krantz has been identified with the 1973 Stratocaster pictured on his early solo albums, but also uses Tyler S-style guitars and more recently, the white Suhr S-style pictured. Krantz tends to downplay the importance of equipment beyond the guitar itself, generally favouring generic amps rather than ‘boutique’ style models.

While at Berklee, Krantz studied with ‘jazz guitar guru to the greats’, Mick Goodrick, assimilating the language and vocabulary of the great improvisers.

He was, however, soon dissatisfied with his sound and approach as he later reflected: “For a while I sounded like a cross between Pat Metheny and Jim Hall, but when I moved to New York I purged myself of everything and everyone and started over.” Hence Krantz’s unique and idiosyncratic sound, borne of a desire to find a unique approach and sound.

Krantz emerged onto a fusion scene in the early 1990s that was dominated by well-established names like Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Mike Stern and Allan Holdsworth. However, Wayne stood out from their often fat or effects-laden tones with his raw Strat sound and funky, staccato attack.

By the mid-90s he generally eschewed the use of effects, instead preferring a slightly gritty clean tone, employing a heavy pick attack in conjunction with hybrid picking, often incorporating unusual open-string ideas.

Krantz likes to create his own scale formulas based on thinking about intervals rather than conventional patterns ‘inherited’ from learning the CAGED system and three-notes-per-string approach.

Specifically, he often restricts himself to only improvising with just a few notes, choosing a four-fret zone on the fretboard to phrase with. This is designed to break out of the predictable patterns that a player may develop, or jaded vocabulary and well-worn licks. After working through these examples explore these concepts for yourself.

Get the tone

Amp Settings: Gain 6, Bass 7, Middle 6, Treble 7, Reverb 2

As Wayne is famed for his use of S-style guitars go for a spiky, ‘just breaking up’ single-coil tone using a generic American-style amp sound or model. The GT recording was made directly to a computer interface using a Line 6 Helix set to a cleanish Fender amp tone with a slight amount of overdrive. A plate reverb and some digital delay was added in the DAW.

Example 1.

This uses the G Diminished Whole-Half scale to demonstrate some of Krantz’s use of syncopation and space. Where many of the players covered in other chapters present dense lines of continuous 16th notes, Krantz tends to make use of different rhythms and space to create the interest.

The quaver rest on the first beat and the placement of subsequent rests, allows the notes to fall on the ‘off’ beats so as to sound less predictable and more interesting.

Example 2.

Here’s one way Krantz uses superimposition; a Cm7b5 arpeggio is played over a G Minor chord to generate the 4th (C), b6th (Eb), b3rd (Bb) and 7th (F#/Gb) intervals.

Example 3.

Krantz often makes use of open strings for tension notes such as Minor 2nds. This is a G Dorian scale run at the 10th position, but every time an open string is available for a scale tone it is played instead of the fretted note.

This mixing of fretted notes higher up the fretboard with open strings creates an interesting texture that guitarist Bill Frisell also employs. You can already see from these few examples how Krantz is anything but your run-of-the-mill fusion guitarist.

Example 4.

This presents another tension device used by Krantz: the Whole-Tone scale. The example also uses chromatic passing notes to bridge the two-fret gap between all of the scale tones.

This adds interest to the symmetrical and somewhat predictable nature of the scale. A good rule in using this scale is to make sure that the 3rd of the chord that you are playing the scale over is included in the line to create some sense of consonance.

Example 5.

In terms of harmony and scale-chord connection, this largely uses the G Dorian scale with some chromatic passing tones. The 16th-note rests add rhythmic variety and lend a funky quality to the line that works particularly well on a Stratocaster whose relatively thin tones leave more space than thicker-toned humbuckers.

The example makes full use of all strings when playing G Minor based ideas in the fifth position: note especially the use of the lower strings.

Example 6.

This further explores the lower registers of the guitar, in an example of how Krantz might use a melodic cell consisting of three or four notes which he then moves around in parallel, exploring melodic and rhythmic possibilities while moving between scale tones (consonance) and chromatic notes (dissonance).

Example 7.

The basic concept behind this is that of superimposing a bluesy chromatic C7 line over G Minor in the first two bars.

This C Mixolydian over G Minor essentially amounts to a G Dorian line but with a slightly different emphasis from simply thinking ‘G Minor’. The second half of the line uses open-string pull-offs, somewhat in the manner of a country or rock player but with a tighter, funkier rhythmic sensibility.

Example 8.

This uses open strings and the G Dorian tonality but this time the line rapidly ascends the fretboard using sextuplets. Again, the technical difficulty is maintaining evenness and clear articulation across the line. The Pentatonic phrase that ends the line adds two16th-note rests for some syncopation.

Example 9.

We start with conventional jazz-fusion 16th-note phrasing but the repeated figure in bar 2 which jumps octaves twice, is a simple concept that adds an unusual twist to the phrasing and melodic contour of the line. The final bar returns us to the more conventional phrasing of the first.

Example 10.

The choppy stop-start rhythms and choice of G Diminished (Whole-Half) over G Minor in this generate considerable tension. The note choices broadly amount to an Eb7 Altered sound superimposed over the underlying G Minor tonality resolving to an idea consisting of stacked 4ths from G Minor Pentatonic.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“There are so many sounds to be discovered when you get away from using a pick”: Jared James Nichols shows you how to add “snap, crackle and pop” to your playing with banjo rolls and string snaps

How to find new approaches to blues soloing – using fingerstyle improv ideas and Roy Buchanan-inspired licks

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)