“I’m playing a nice old Gibson ES-335 through Lowell George’s Dumble amplifier…” Joe Bonamassa brings out the holy grail gear to explain how to get into a slow blues jam – and, crucially, how you can get out of it

In this exclusive video lesson, the bluesman walks us through an essential skill for the blues guitar player, the slow blues… And he’s going to demonstrate how using an amp it took him 15 years to track down

One of my favorite things to play is a slow blues song, which is something I include in every performance. Each time, without really thinking much about it, I’m faced with two questions: 1) How does one get into a slow blues?, and 2) How does one get out of a slow blues? Sometimes, it’s harder to get out of it, especially when you’re caught up in playing widdly-widdly fast licks.

For today’s examples, I’m playing a nice old Gibson ES-335 through Lowell George’s Dumble amplifier, which was built May 8, 1976, by Alexander Dumble. It took me 15 years to track down this tube amp, and I’m about to bring it out with me on the road.

A slow blues tune that I’ve played often over the years is Blues Deluxe, which was originally recorded in 1968 by Jeff Beck with Rod Stewart for Beck’s debut solo album, Truth. Blues Deluxe is really a hybrid of two other blues songs, Stone Crazy and Gambler’s Blues, lyrically speaking. I covered the song for my album Blues Deluxe in 2003.

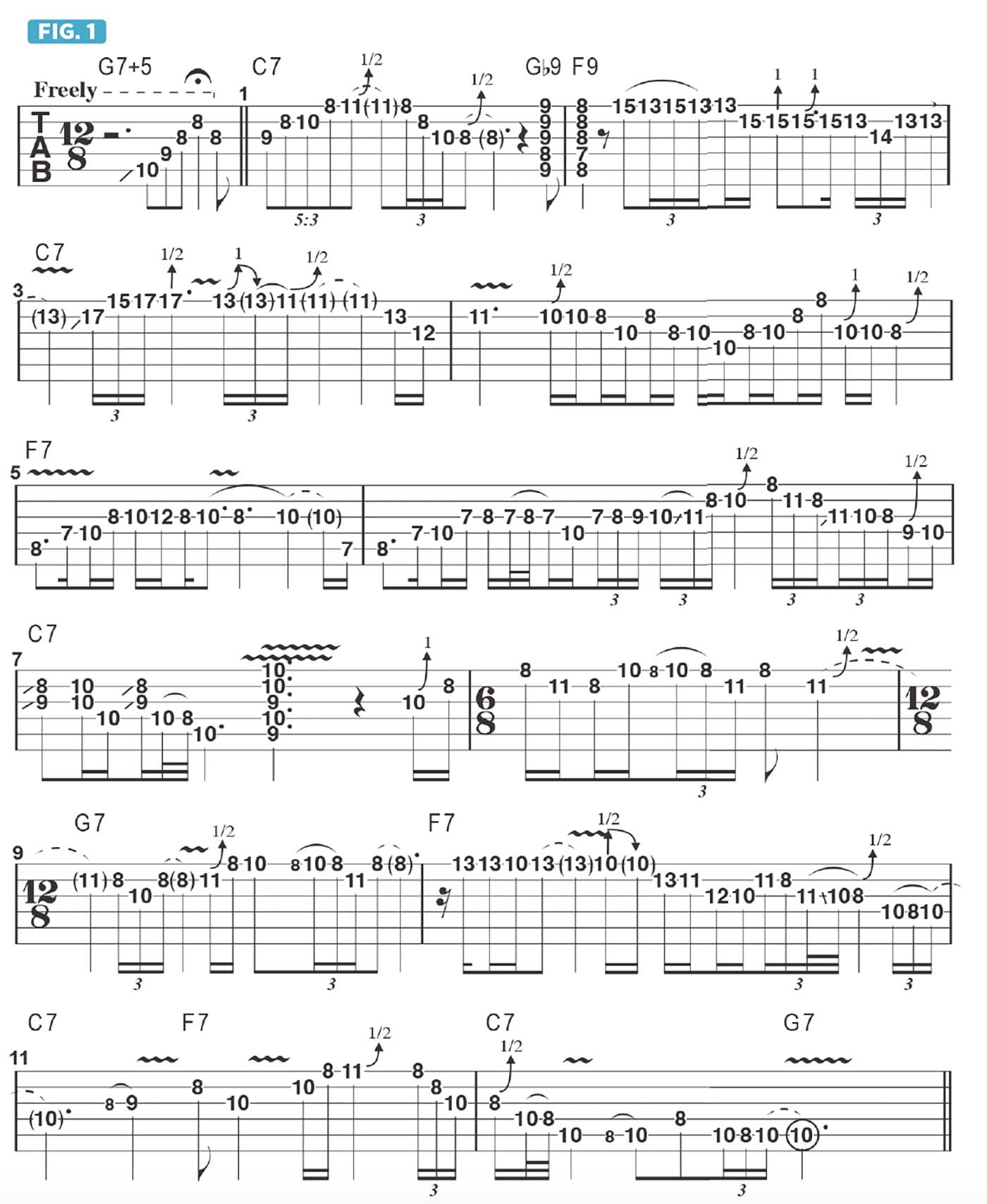

I often like to kick off a slow blues tune by starting, unaccompanied, with an augmented arpeggio on the V (five) chord, before cuing in the band. Blues Deluxe is in the key of C, so that would be a G augmented arpeggio (G, B, D#), as shown in the pick-up bar of Figure 1.

In bar 1, the 12-bar blues form begins, and over C7 in this example I start with a B.B. King-style lick that’s based on a combination of C major pentatonic (C, D, E, G, A) and C minor pentatonic (C, Eb, F, G, Bb). Over the “quick change” to the IV (four) chord, F9, in bar 2, I move up to 13th position and play an Eric Clapton-style lick based on C minor pentatonic.

On the return to C7 in bar 3, I briefly shift up to 15th position and then down to 11th position, ending the phrase on Bb. In bar 4, I repeat the Bb note by bending up to it from A, one half step below, having shifted down to 8th position for the C minor pentatonic-based I phrase play through the remainder of the bar.

Bars 5 and 6 are played over F7, and in this example I blend the notes of an F7 arpeggio (F, A, C, Eb) with those of C major and minor pentatonic. Notice also the brief use of chromaticism in bar 6.

Bar 9 moves to the V (five) chord, G7, with notes referencing G minor pentatonic (G, Bb, C, D, F), and over the F7-to-C7 change in bars 10 and 11, I simply return to phrases built from C minor pentatonic. The solo wraps up with a classic turnaround-style lick in bars 11 and 12.

I think of this as more of a “British” approach, with a mindset more to Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor than B.B. King or T-Bone Walker.

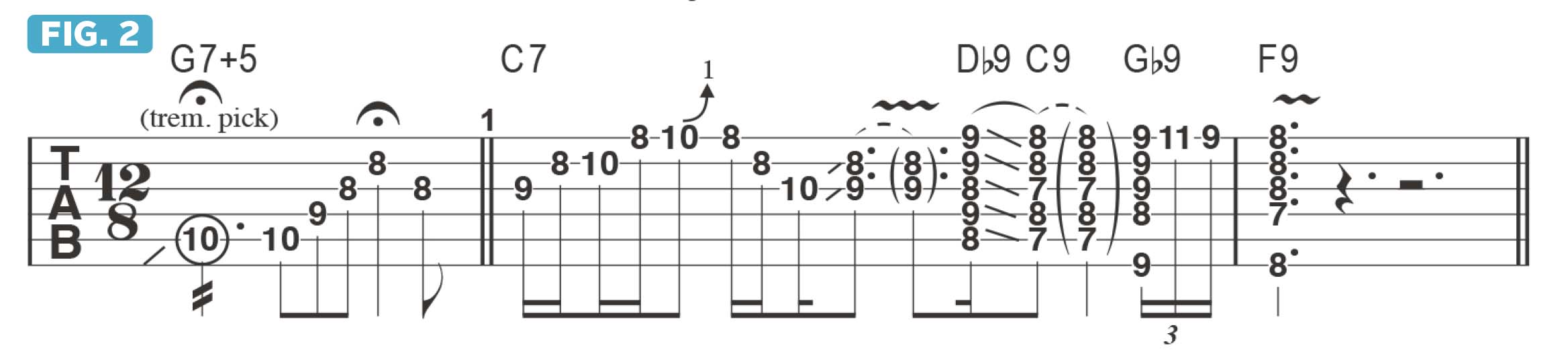

I like to draw listeners in by starting quietly, as shown in Figure 2. After the free-time G augmented arpeggio, the initial solo lines are played delicately, which allows me the latitude to build intensity as the introduction progresses.

- Blues Deluxe Vol.2 is out now via J&R Adventures.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe Bonamassa is one of the world’s most popular and successful blues-rock guitarists – not to mention a top producer and de facto ambassador of the blues (and of the guitar in general).