“He was able to make each note sound so big. When I formed my first trio the first place my mind would go was the sound of Leslie West’s guitar”: Jared James Nichols explains why Mountain man Leslie West was the “king of heavy”

In this video lesson, Nichols unpacks some of West's signature techniques and demonstrates how you, too, can scale the summit of tone and feel...

For this month's column, I’d like to talk about my biggest guitar hero, Leslie West from Mountain. Leslie was the king of heavy, and the king of tone, phrasing and nuance.

There are a ton of things I took directly from Leslie, such as my preference for guitar pickups. Leslie is famously revered for the incredible tone he got from the single bridge-position P90 pickup on his signature guitar, a Gibson Les Paul Junior.

I remember being a kid, looking at the pictures of Leslie’s guitars on Mountain’s Twin Peaks album and realizing there was something different about his guitar as compared to a Les Paul Standard, which is fitted with humbucker pickups.

My friend told me. “No, Leslie uses a Les Paul Junior with a P90 pickup.” I was blown away by his tone, as he was able to make each note sound so big. Years later, when I formed my first trio, I thought about where I wanted the guitar to sit, sonically speaking, and the first place my mind would go was the sound of Leslie West’s guitar.

Leslie is most famously associated with his classic track Mississippi Queen, which is a benchmark for tone and feel. One of the things that influenced me on that track was Leslie’s approach to chords.

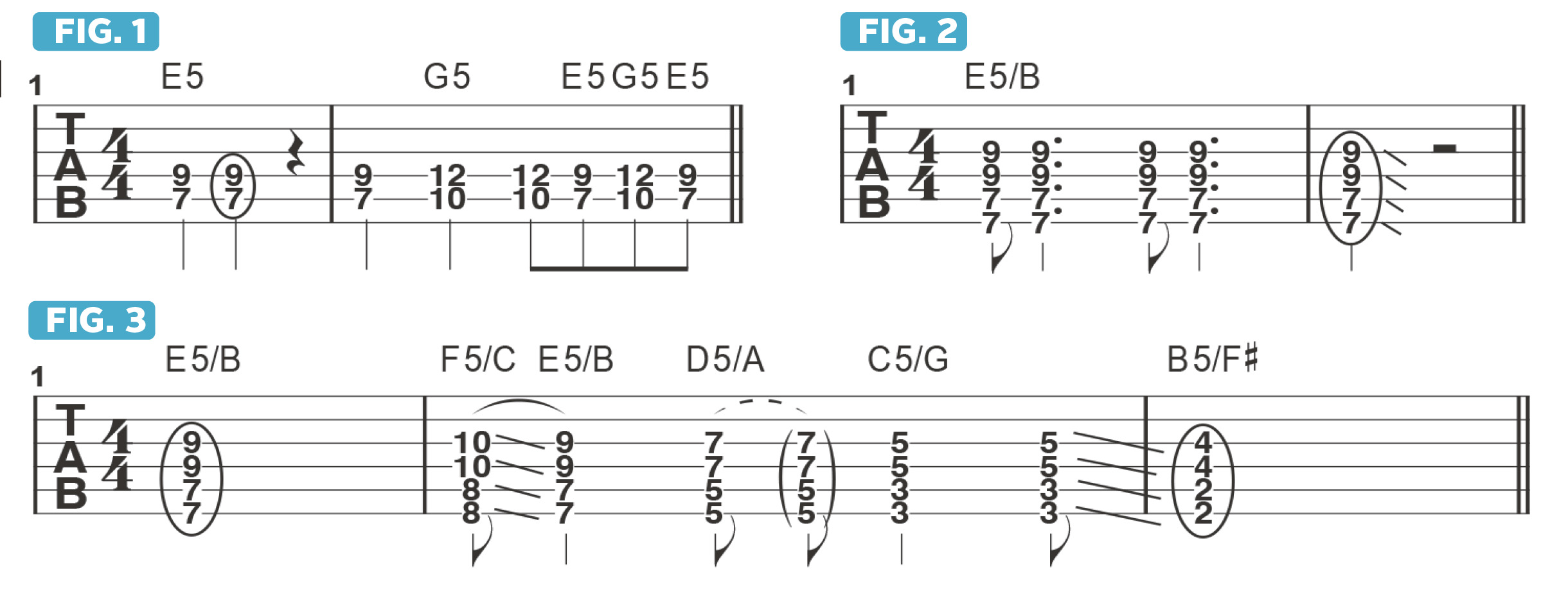

Figure 1 shows a series of standard two-note root-5th power chords played on the A and D strings: starting with E5, I then move up three frets to G5 and then alternate between the two chords.

Leslie would fatten the sound of these power chords by octave doubling each note. As shown in Figure 2, the index finger barres the bottom two strings to sound B and E, and the ring finger barres the D and G strings to sound the same two notes an octave higher.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Octave doubling notes in this way serves to make each chord sound huge. The first time I ever heard Leslie’s use of these voicings was on Don’t Look Around, similar to Figure 3.

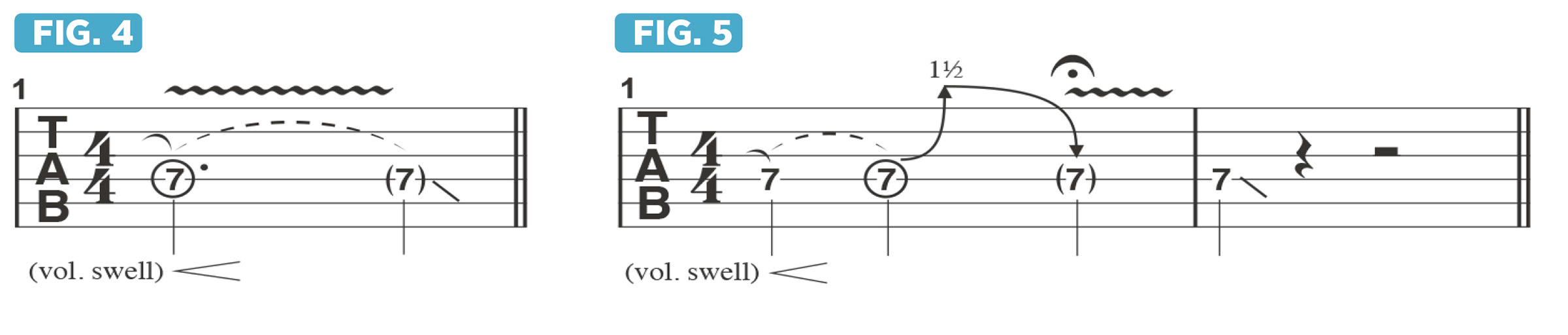

Another technique I copped from Leslie was his use of volume swells. In a live performance, he would often play unaccompanied solos before the song Dreams of Milk and Honey, as he does on Flowers of Evil.

As demonstrated in Figure 4, with the guitar’s volume turned all the way down, Leslie would hammer onto a note then slowly turn up the volume.

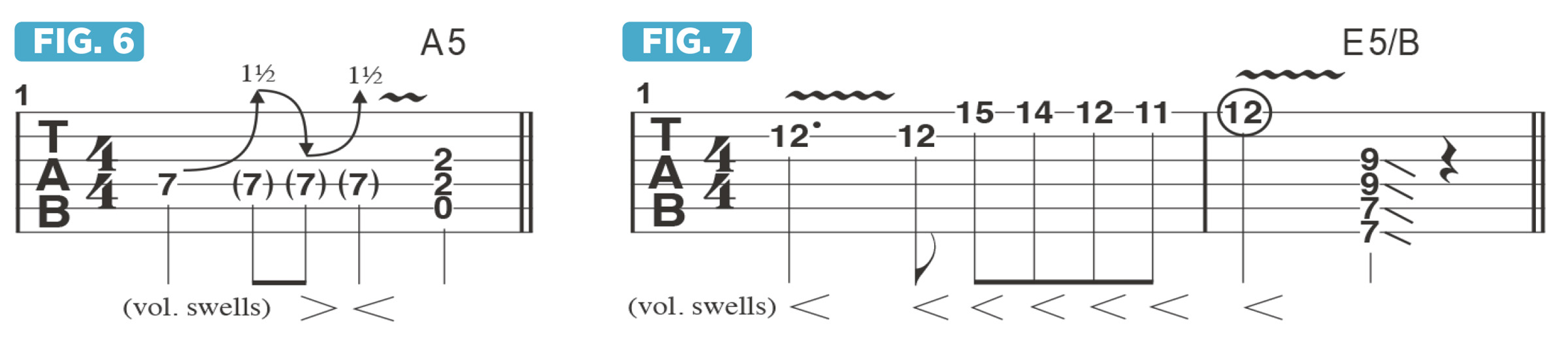

In Figures 5 and 6, the initial note is bent up one and a half steps and then released and vibratoed. The sound produced is akin to that of a bowed note played on a violin or a cello.

Figure 7 demonstrates another way to use swells, as each note is fingerpicked with the volume off and then swelled.

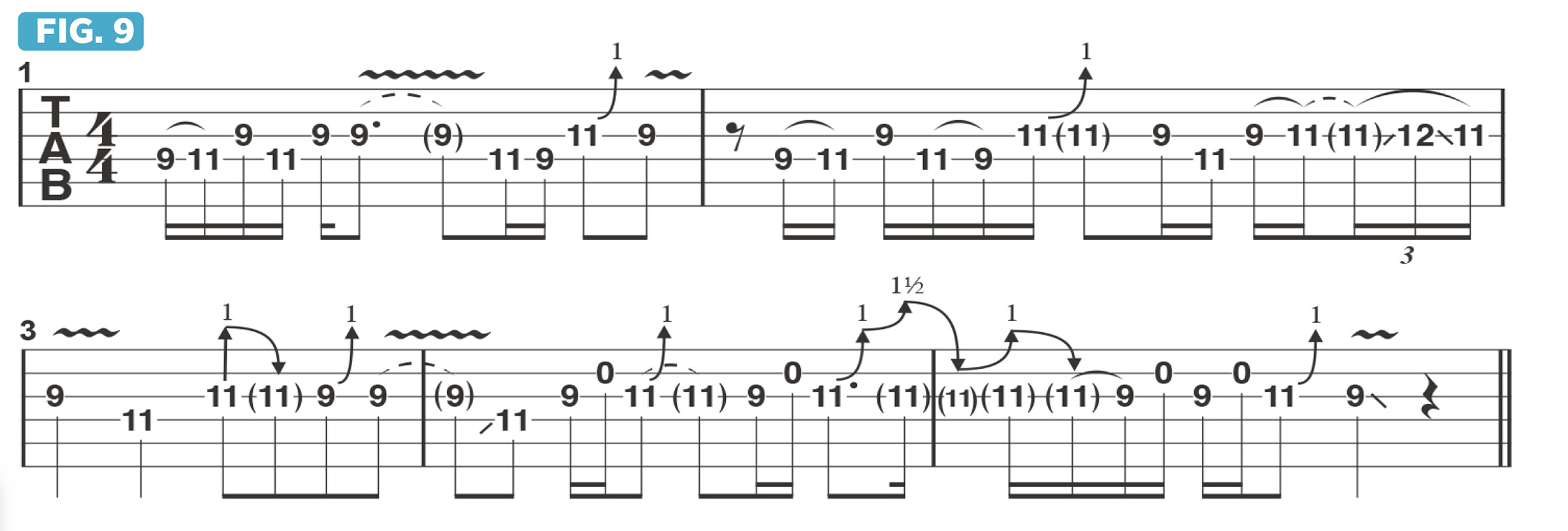

Lastly, Leslie also influenced me to lean on major pentatonic licks along with minor pentatonic licks.

Figure 8 begins with E minor pentatonic (E, G, A, B, D) and then switches to E major pentatonic (E, F#, G#, B, C#). FIGURE 9 offers a longer example of how Leslie might stick with major pentatonic to weave long, beautifully melodic phrases, offering a great, warmer sounding alternative to minor pentatonic-based phrases.

Jared James Nichols is a blues-rock guitarist with two signature Epiphone Les Paul models (and a Blackstar amp) to his name. His latest album is 2023's Jared James Nichols.