“A lot of guitarists who can play killer leads get real sterile on their rhythm stuff – they’re all too careful about playing their chords dead straight”: Dimebag Darrell wrote 42 lesson columns for Guitar World. Here’s the best advice he shared

We’ve collected the best of Dimebag’s “Riffer Madness” columns for the ultimate masterclass in the late Pantera guitarist’s trailblazing style

But first, a brief backstory by Nick Bowcott! Back in 1993, GW’s editors decided to run with an idea that would become a mainstay of the magazine to this day – monthly artist columns.

Two bona fide guitar heroes, Kirk Hammett and Eric Johnson, agreed to do six installments each, but the editors wanted to enlist one more columnist, ideally an up-and-coming player.

Because I had been commissioned to work with said artists on putting together their columns, I was asked if I had any suggestions. My answer was instantaneous – “Diamond Darrell of Pantera. He’s the one!”

I had previously interviewed the guitarist for a one-off lesson article for the magazine and was blown away by his playing, personality, passion and unique and colorful way of explaining things, which the guys at GW and I came to lovingly refer to as “Dimebonics.”

He and I had also become good friends, so I knew working with him would be a blast. Editor-in-Chief Brad Tolinski agreed and, thankfully, so did the Texan Tornado. And so Diamond Darrell’s “Riffer Madness” column was born.

NOTE: Up to and including Pantera’s pivotal sophomore major-label album, 1992’s Vulgar Display of Power, Abbott’s nickname was “Diamond Darrell.” But when Far Beyond Driven was released in 1994, his name was listed as “Dimebag Darrell.” Said album reached Number 1 on the Billboard 200 chart, and the rest is history.

As already mentioned, the initial plan for Riffer Madness was a six-issue run. But due to the enthusiastic reader response to the first few installments, he was soon asked if he’d like to continue the column.

Thanks to all the positive feedback he was getting, plus the fact that he genuinely enjoyed writing the column, he happily agreed. As a result, that first run of monthly columns totalled 28, all bearing his Diamond Darrell name.

Then, in 2000, the celebrated guitarist-turned-columnist returned with another 14 installments, this time as Dimebag Darrell. His plan was to return for a third run in 2005, but, tragically, that never happened.

To celebrate the amazing 42 Riffer Madness episodes that Darrell selflessly gifted us with, here’s a collection of column highlights that focus on the all-important arts of riffing and rhythm work. So, as Dime stated when Riffer Madness debuted in the April 1993 issue of Guitar World, “Let’s plug in and start wailin’!”

Without further ado, I hand the pen over to Mr. Abbott.

Riff rap

To me and my band, guitar riffs are what it’s all about. We know that every time we jam on a great riff, we’ve got a fighting chance of writing a great song. You don’t have to go to G.I.T. or know a bunch of weird-assed chords and scales to come up with killer shit, Jack.

But, you’ve gotta be totally into what you’re doing. Check out Judas Priest’s British Steel if you don’t believe me. It’s packed full of god-like riffs, and most of them aren’t hard to play. If you don’t already own this album, buy it – it’s essential shit, man! Here are a couple of ideas that might help you get the most out of a good, heavy riff.

Octave repeats

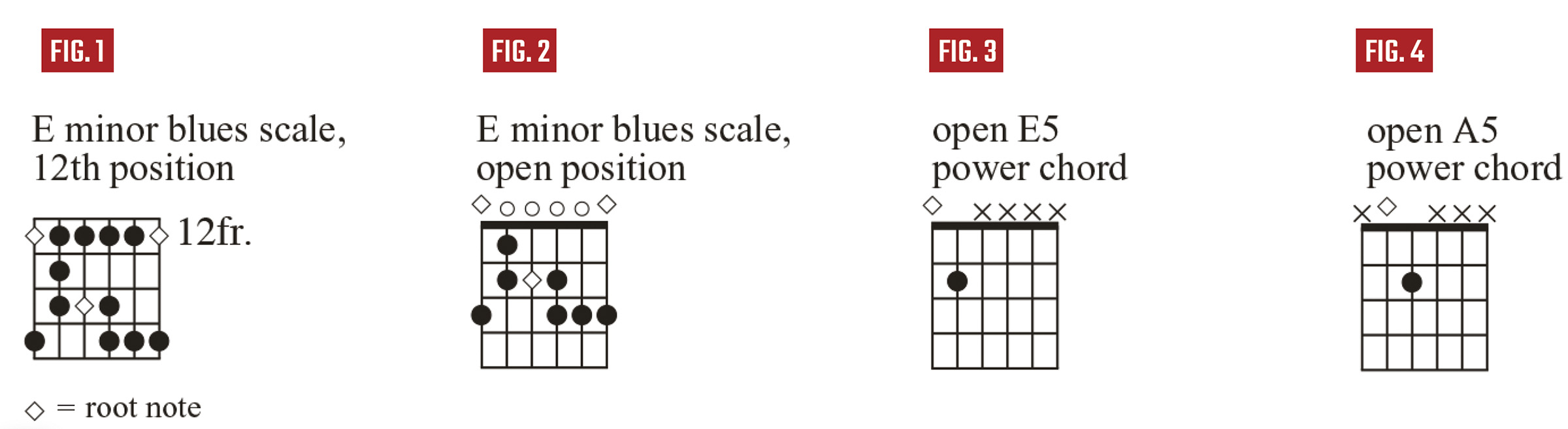

One of our audience’s favorite riffs is the main one in Cowboys from Hell. It’s a pretty easy one to play ’cause it’s made up of one of the first rock scales we all learn – the E minor blues scale (see Figures 1 and 2).

The first time you hear this riff is in the intro, where I play it an octave higher than I do during the rest of the track. Hearing it an octave higher is like an appetizer – it introduces you to the riff and makes you hungry for more. It also makes the full-blown version sound really heavy when it kicks in. I guess you could say the intro is the “body blow” and the main riff is the “knockout punch.”

My buddy Jerry Cantrell from Alice In Chains does the same sort of thing on Would? [from Dirt]. He starts off by playing the verse riff in a higher register then slams you in the teeth when the vocals hit by playing it an octave lower.

To give the main Cowboys riff even more power, I play open-string root-5th power chords on the E and A notes (Figures 3 and 4) instead of just playing single notes, as I do in the intro. I also add some low-end “chunk” to the riff by applying some heavy-duty palm muting (P.M.).

I use the idea of repeating a riff in different octaves during the bridge of Cowboys, too. This definitely makes that part sound cooler than if I had just played that [descending] run in the same register twice.”

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Dime also often used this compositional technique of repeating a musical motif an octave higher or lower when playing lead, like at the start of his epic solo in the aforementioned Cowboys from Hell and also the one in Psycho Holiday (Cowboys from Hell), to name but two. Check them out. It’s an idea well worth embracing!]

Texas-style half-step bends

Using string bends instead of just playing regular, unbent notes can definitely help give certain riffs a cooler, heavier vibe.

- Note: For Figures 5 to 13 guitar is tuned down one whole step D-G-C-F-A-D

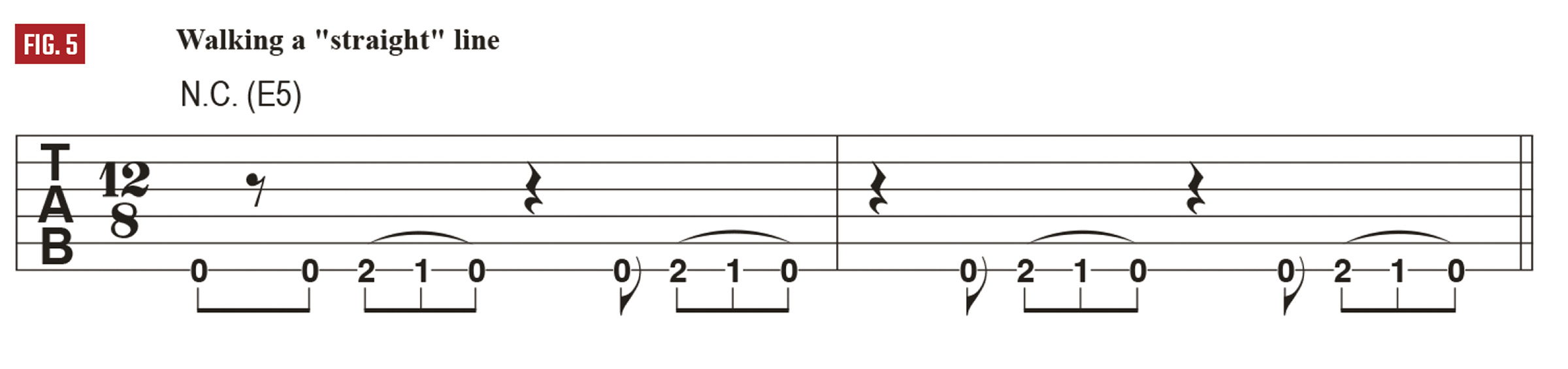

Take the opening riff to Walk, for example. I guess you could play the notes “straight” without the “greasy” string bend-and-release (Figure 5 illustrates said “straight” approach), but the “real way” sounds way better to me, man! It’s much heavier and nastier, and that’s what we’re looking for, bud – weak riffs are out!

I do the same kinda thing on the opening riff to Revolution Is My Name (Reinventing the Steel). Here’s the twist I put on it… I call it “Texas style!” What I do is scoot back a fret from the notes I heard in my head and then bend up to each one from a half step below while also adding a pick squeal (Figures 6a and 6b).

When I was jerking around with the original riff idea, I figured it would sound way more interesting if I did a slow, deliberate half-step bend up to each one, because as soon as each bend starts, your ear wants to hear the note come up to pitch.

Some people do this sorta thing a lot when they’re playing lead, but most of ’em don’t bother to do it at all when they’re riffing out on the low strings.

For some reason, a lot of guitarists who can play killer leads get real sterile on their rhythm stuff; they don’t bend notes, and they’re all too careful about playing their chords dead straight. Then, when they cut to lead, they start bending notes and adding vibrato all over the place.

Lead rhythm and bending chords

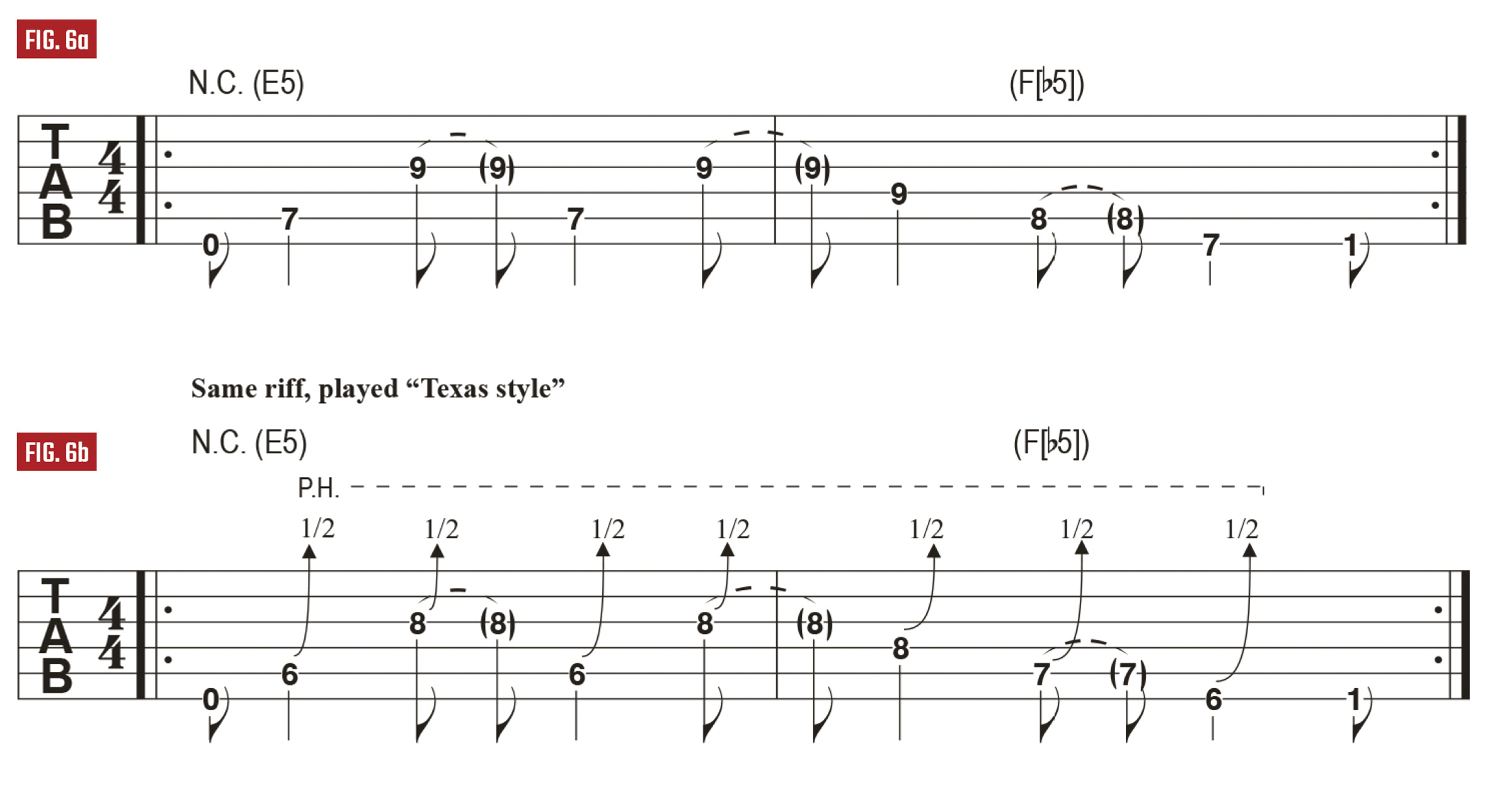

The way I’ve always looked at my rhythm playing is almost like I’m playing lead on the big strings anyway. Because of this I use vibrato and bends on the big strings as well as one the little ones… and not just on single-note stuff, either. Sometimes throwing down a bend or some vibrato on a power chord is cool, too! For example, let’s take a fairly mediocre riff like Figure 7a.

To make it more evil and interesting sounding, try this: instead of using a regular G5 power chord, bend an F#5 shape up to G5, like in Figure 7b. Bending two different notes up exactly half-a-step at exactly the same time is kinda difficult at first, but stick with it ’cause it sounds great when you get it down. You can hear me doing this at the end of Hollow (Vulgar Display of Power).

Don't skitz – hang tough!

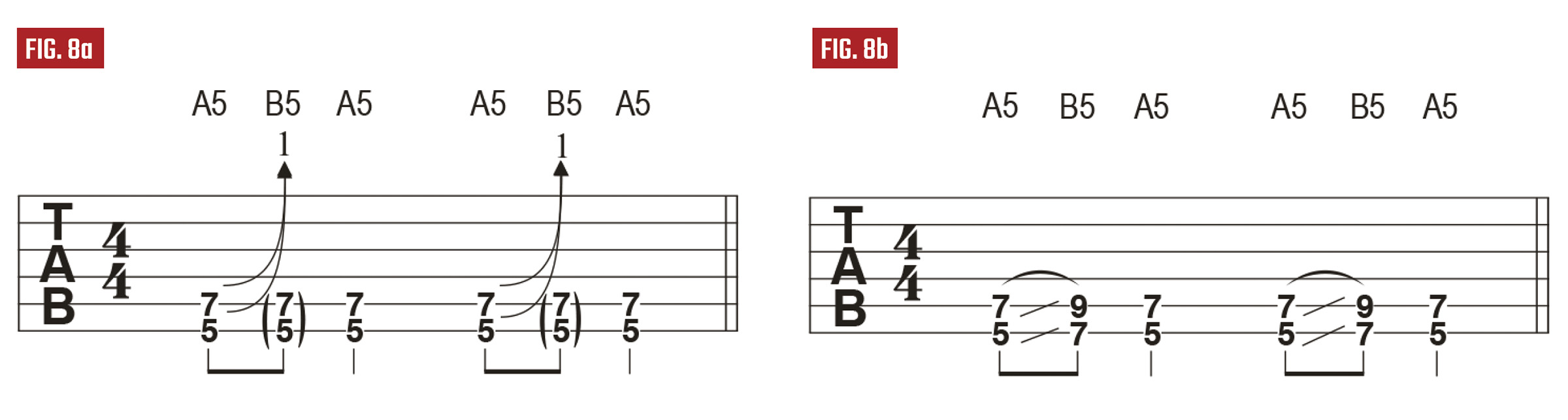

The breakdown riff at 2:05 in We’ll Grind that Axe for a Long Time (Reinventing the Steel) has got some [root/5th power] chord bends happening, too, and they’re actually whole-step bends. To do each bend, I pull the low E string (which is tuned down to D) with my index finger and the A string (tuned to G) with my pinkie, with some help from my ring finger (Figure 8a).

The bend raises the pitch of the chord the same as if you were to slide it two frets up the neck (Figure 8b), but it’s smoother sounding. That’s why I chose to go with the bend instead of the slide. Half the trick of this move is trying to keep the chord decently in tune while you’re bending it.

If your 1st finger bends more than your pinkie, then the chord is gonna go sour. Don’t get me wrong – it’s cool to get a little out of whack, but at the same time you’re trying to hold the chord in tune as much as possible while the bend is going on. It’s a total ear/feel thing – your ear is wanting to hear something and is telling you where to go while your fingers are feeling and controlling the bend.

Don’t freak if you can’t nail these chord bends right away. Just keep hanging with it and it’ll come. Because you’re bending the big strings here, you might have to do it a few times to build up some strength in your fingers, if you’re not used to doing it. There’s a lot more mass down there, compared to the thinner strings!

Also, you obviously have to bend the low strings by pulling them into your palm rather than pushing them upwards, like you normally do with the little strings, so that might take some getting used to, as well.

The fact that my guitar is always tuned down a hair lower than a quarter step below concert pitch, plus down an additional whole step in this case, helps with the looseness of the strings. But it’s still a pretty big bend. It doesn’t have to be perfect, though. So just catch a vibe and roll with it.

Unique tuning offset

Editor’s Note: Per Darrell’s renowned, long-time guitar tech, Grady “Dragon” Champion, here’s the scoop on Dime’s unusual guitar tuning offset: Whether it’s down a half step (Eb standard), drop-D, drop-C# or some other variant, it was always an additional 60 cents flat of concert pitch (slightly lower than a quarter tone, which is 50 cents).

Says Grady: “To us, E is really D# plus 40 cents. Likewise, A is really G# plus 40 cents, D is really C# plus 40 cents, and so on.” Now you know why it’s so hard to tune to a lot of Pantera songs.

Sinister slides

Sliding from one power chord to another can also help make a riff sound more sinister. I got the idea from listening to Tony Iommi in Black Sabbath, and I do it a lot.

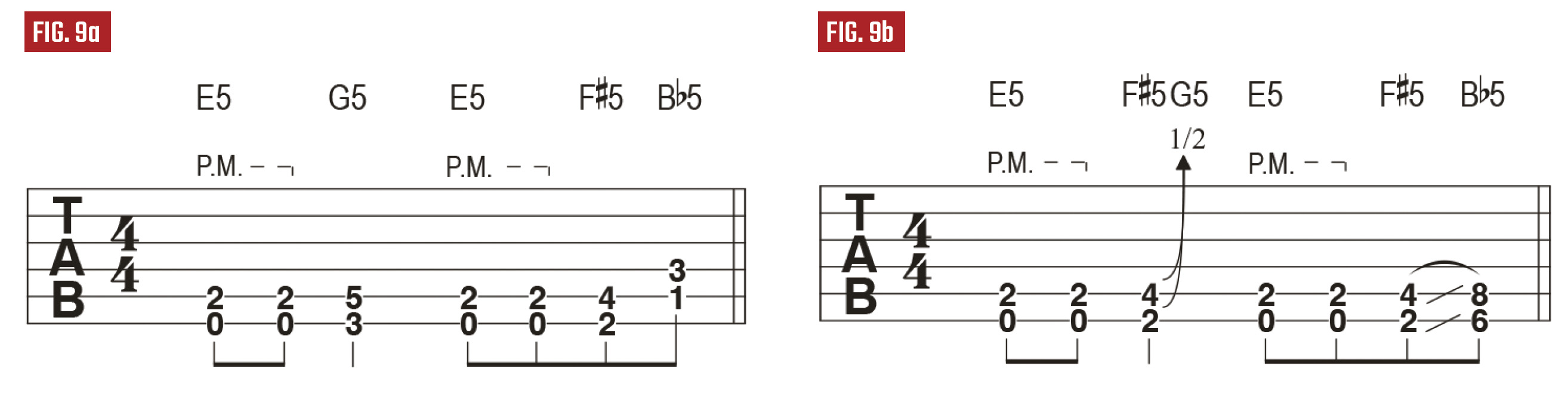

For example, check out Mouth for War (Vulgar Display of Power). So, if I wanted to make a riff like Figure 9a sound nastier, I’d probably throw in a chord-slide and maybe a chord-bend too (Figure 9b).

Which one sounds better? C’mon, there’s no contest! Figure 9b kicks Figure 9a’s sorry ass! Like I’ve said before, sometimes even the simplest shit can be really bad-assed… as long as it’s played aggressively. It’s all about attitude, man – meaning playing it like you mean it!

Long, single-note slides

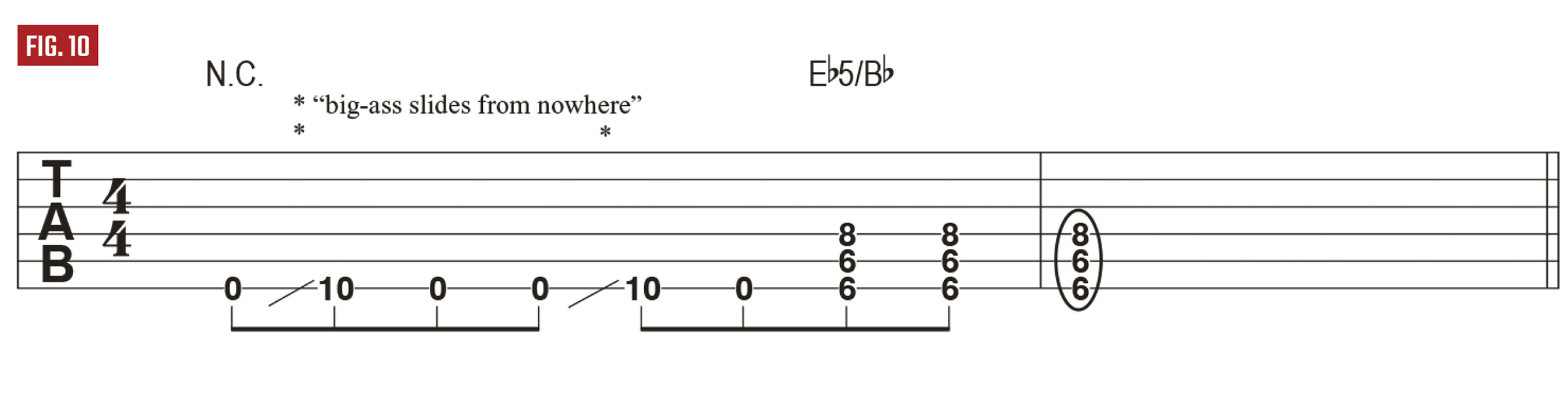

There are two things you have to remember when doing really long slides that don’t have a set starting place, like this one, “from nowhere in particular” to the 10th fret on the 6th string (Figure 10), which is along the lines of what I do in the verse riff of Goddamn Electric (Reinventing the Steel).

First, you’ve gotta let off the strings a tad with your fret hand and just let them slide under your fingers. If you press too hard on the strings when you’re doing a long slide up or down the neck, it probably won’t come out right.

It's about the destination, not the journey

The other thing to remember when you’re sliding a long way is this: it’s the destination that’s important, man. It doesn’t really matter how you get there or where you start the slide.

The trick is knowing where to stop and making sure that you don’t get there too early or too late. So, keep your fret hand loose, use your ears and eyes and, with a bit of practice, you’ll be nailing long assed-slides like the ones in the Goddamn Electric verse every time.

Rules? There are no rules

My musical knowledge is pretty limited, scale-wise. I know the major scale, the minor scale, the pentatonic blues scale and the chromatic scale, but that’s about it, man! If I can learn a new scale somewhere I’m definitely open to it. I’m not down on scales, it’s just that I’m more into riffing and jamming as opposed to book-school theory reading.

“Be raw” – that’s what I always say. I’m always experimenting with new note ideas because in my style there are no rules. Always remember this, and never be afraid to cut loose.

Hell, if you find yourself hanging on a bad note, you can always tighten it up by bending, sliding it, or dumping or yanking your whammy bar… don’t skitz on this though, just keep an open mind and experiment. Whatever the song calls for and whatever you’re hearing is fair game.

Chromatic man

In case you don’t know what chromatic means, let me explain: it means every goddamned note! So, to play chromatically, all you do is move up or down a string one fret at a time.

Simple shit, but it can sound really cool. I use chromatic movement a lot in my riffs because it adds a pushing/pulling kinda tension. It almost reminds me of running up and down a flight of stairs, one step at a time – 12 steps to the top, and 12 steps to the bottom.

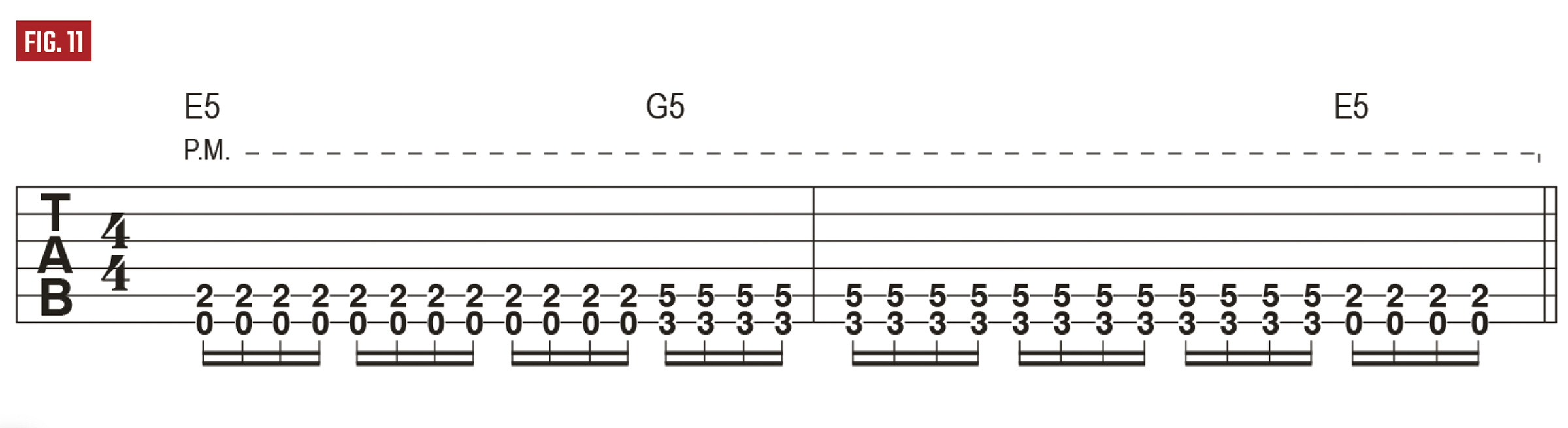

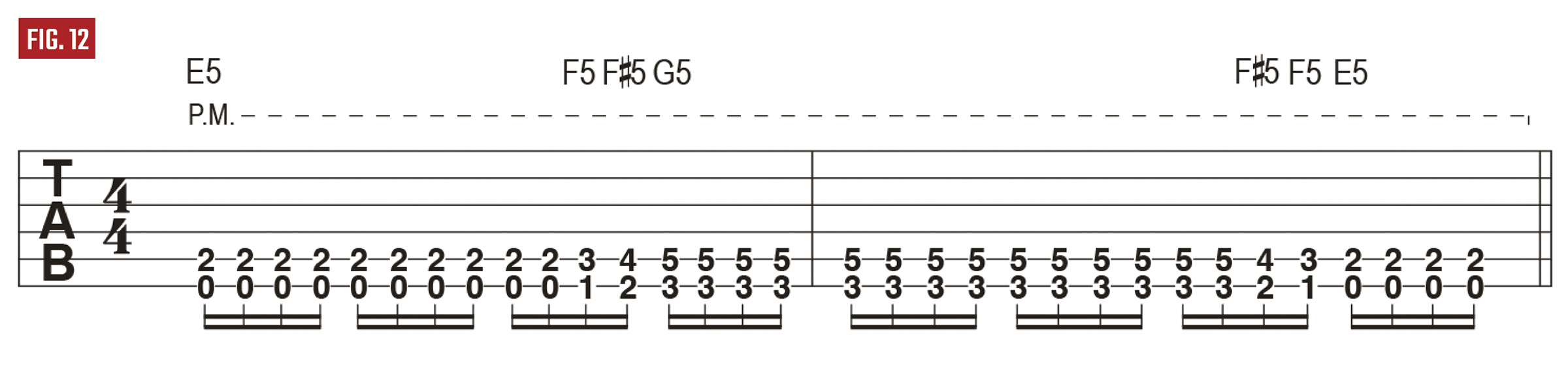

A chromatic passage can add mood and aggression to a part. If you’ve never dicked around with this idea, then check this out. Say you have a simple riff like Figure 11. Instead of just going from E to G and then back to E, try moving between them chromatically, like in Figure 12.

You can do this between any chords or notes. It just depends on what you wanna create. This is a simple idea, but it kicks ass.

Scope it out and then take it further. Good examples of riffs based on chromatic thinking are the main one in A New Level (Vulgar Display of Power), the pre-chorus of Cowboys…, the first bridge riff of This Love and pretty much all of the riffs in We’ll Grind That Axe for a Long Time. That last cut is big-time chromatic.

Hopefully this will inspire you to jam out some cool chromatic-based riffs of your own. Keep shredding ass and hang raw!

Palm muting tips

Palm-muting a note or power chord by resting the heel of your picking hand on the strings as they go over the bridge is a pretty basic and essential metal guitar playing technique that, if done correctly, can add a shitload of ballsy chunk to a riff. But there are a couple of things you have to watch out for when doing this.

For me, the best place to palm-mute the strings is right where they go over the bridge or just a hair in front of that. If you go too far forward though, you’ll choke the string so much it’ll just be dead-sounding and will make a racket rather than a note. Also, you don’t want to go too far back the other way either, otherwise you’ll end up muting jack shit. So, dick around until you find the sweet spot that hums – you’ll definitely know when you find it.

Don’t be too heavy handed when palm-muting, especially if you’re using light strings and you’ve got your action set low. Some nights when we’re playing live, I’ll be really fired up and will be playing so super-hard that I won’t even be aware that I’m just crunching down on my muting so hard that it doesn’t even sound like I’m playing notes anymore.

This happens because I’m pushing the strings down so far that they start kinda hitting the frets and making a weird, clanking noise. Whenever this happens, I’ll walk back to my rig and my tech Grady [Champion] will go, “Ease up, son; you’re killing it!”

Seeing as guitar playing is either muscle or finesse, if you’re gonna strangle it then use heavy-assed strings with an action that’s set high enough, so you have more room to lean into the strings. If you choose to go this route, you’ll be able to pretty much mute as hard as you want. Keep in mind though, that setting your guitar up this way will also make it much more difficult to play.

If your axe has a whammy system, like a Floyd Rose, and it is set up to be “floating,” so that you can pull notes up as well as push them down, that’s another trick you’ve got to master.

With a floating bridge, you have to be real careful when palm muting because, if you rest your hand too far back on the bridge, then you’re gonna push the back of it down and make your strings go sharp. Of course, this isn’t a problem if your guitar has a fixed bridge or a non-floating tremolo setup.

Choking up on your pick

Another thing to watch out for when you’re chunking on a fast riff is not to stick your pick too far into the strings. Think about it. You can’t really haul ass if you’re pulling a big piece of the pick across the strings, can you?

Also, doing this can make the string start flapping too much and, if you’re not careful, that starts messing up the pitch of the note.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not suggesting that you pitter around and play wimpy. I’m just saying that it’s a good idea to “choke up” a little bit on your pick, clasping it a little bit closer to its pointy tip, so that too much if it isn’t sticking out past your fingers.

The ups and downs of picking

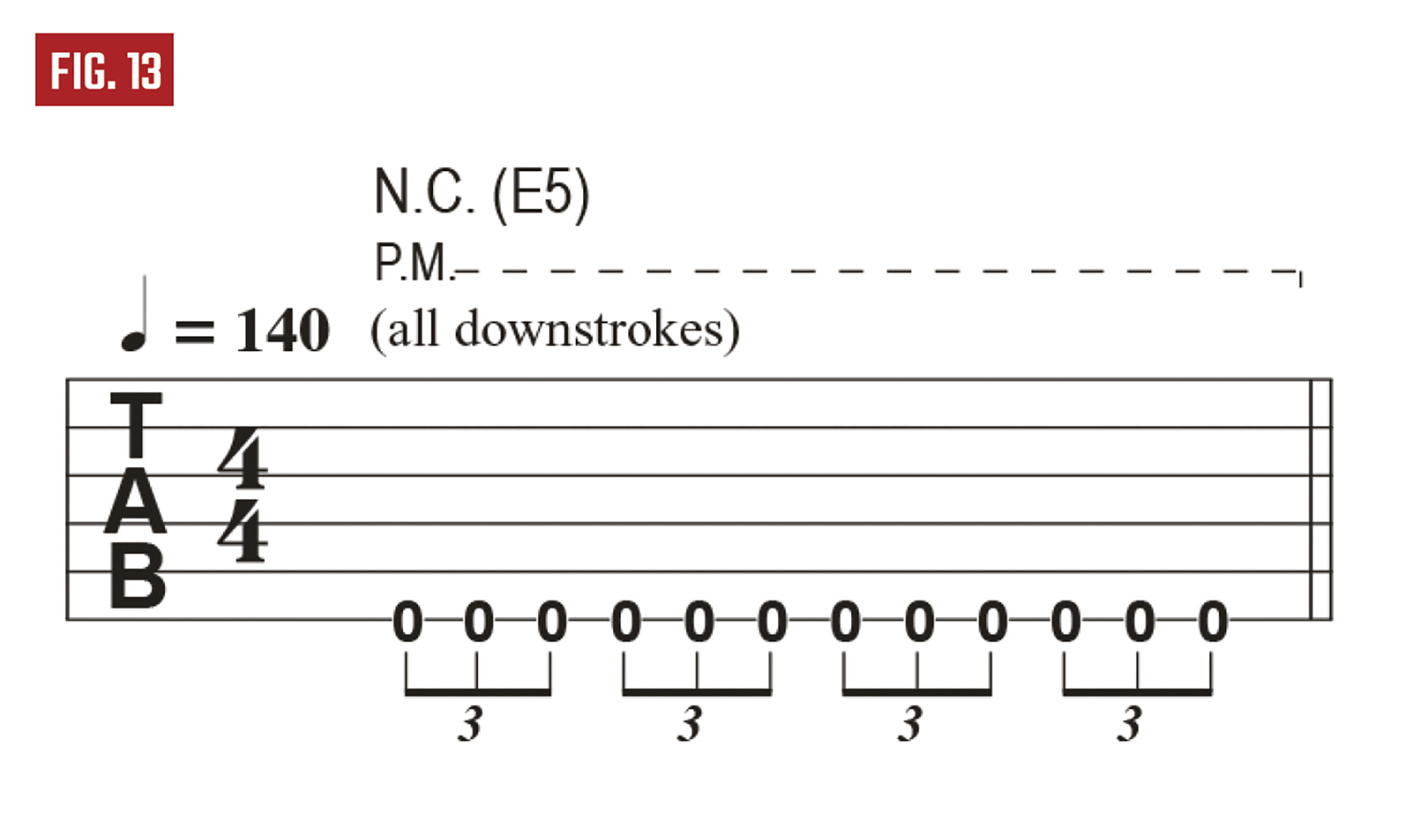

To make sure I get maximum chunk happening on the palm muted low-string sections of a riff, like the pre-verse riff of Revolution Is My Name (Reinventing the Steel), I play ’em using downstrokes only.

Actually, that first bar, which is eighth-note triplets played at around 140 beats per minute, as in Figure 13, is pretty close to my breaking point. If it were any faster, I’d probably switch to alternate (down-up) picking. I’d imagine that’s true for most people… unless, of course, you’re James Hetfield! That dude is the king of down picking, no question about it.

Sometimes I feel I can get more chunk and grind by using upstrokes too, so I’ll alternate pick. Upstrokes definitely have a different attack than downstrokes, and this can suit certain riffs better

As I’ve said a lot of times in interviews, I don’t necessarily try to play everything using just down picking as a rule anyway, because I do a lot of up picking in songs like Cowboys… and whatnot. Although downstrokes are more consistent, mechanical and machine-gun like.

But sometimes I feel I can get more chunk and grind by using upstrokes too, so I’ll alternate pick. Upstrokes definitely have a different attack than downstrokes, and this can suit certain riffs better.

One of the cool things about upstrokes is, when you’re doing them on your low E string, you can dig in deep with your pick and hit the string real hard without having to worry about hitting another string.

Also, the way I do upstrokes is almost like I’m doing a pick scrape. As opposed to just picking straight across the string, I kinda drag the pick across it to get a “scrap” happening just before the note sounds.

Pick scratching, not scraping

When I play live, I jump around like an idiot for 90 minutes under a lighting rig that’s hotter than hell. This makes me sweat like a pig and makes it really hard to keep a firm grip on my picks, even those that are supposed to be non-slip.

Losing control of your pick on stage sucks, so either I or Grady scratch some deep Xs into both sides of my pick (see photo above) with something sharp like a dart. Doing this makes your picks look like shit, but at least you won’t look like a nincompoop when you drop one in the middle of a solo!

Learning from others by listening

Some folks tend to get really intimidated when they come across someone who really rips on guitar. But not me, pops. I get inspired! As far as I’m concerned, playing is not a competition. Hearing someone smoke always lights my fire and makes me try out new ideas and learn new shit.

I don’t sit down with a pile of records and try to cop licks, though. What I’m into is checking out the player’s overall vibe and approach and learning from that. Use your ears and learn all you can from anything. Listen!

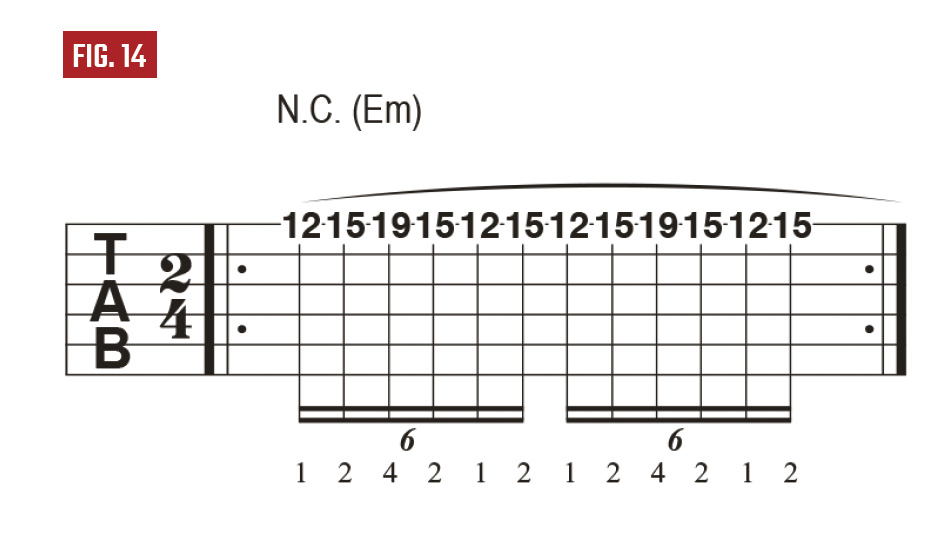

Pinkie power and EVH

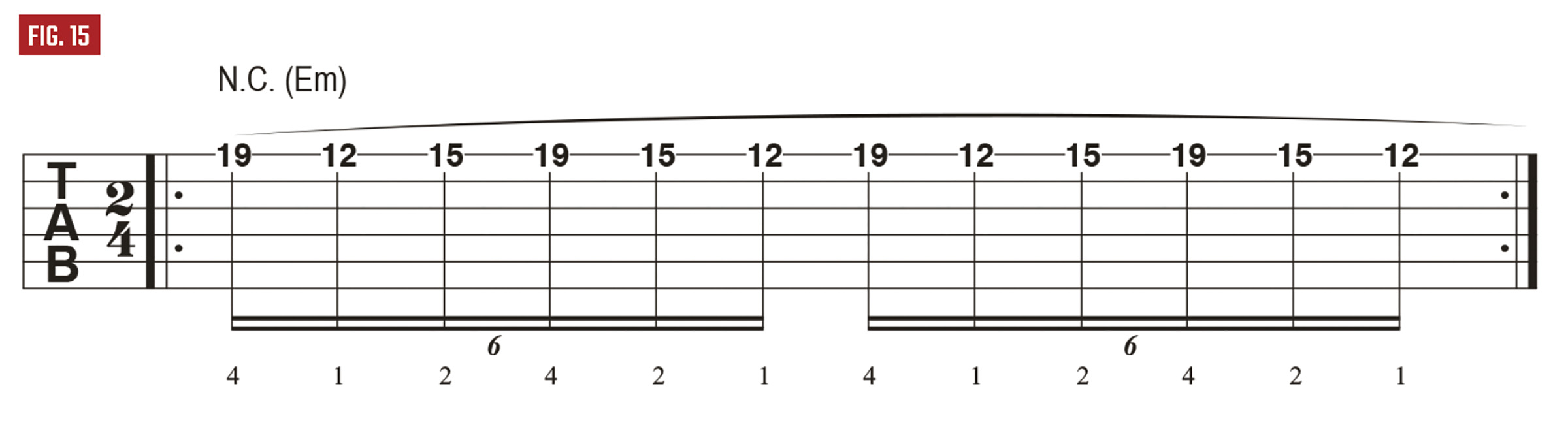

When I first started playing guitar, one of my biggest influences was Eddie Van Halen. I kept seeing pictures of him doing big-assed left-hand stretches, and that inspired me to start dicking around with some wide-stretch ideas of my own, like the two E minor licks in Figures 14 and 15.

Another thing I learned from studying those pictures was the importance of my little finger. It’s there, so use it! It definitely gives you more reach!

Awkwardly cool symmetrical runs

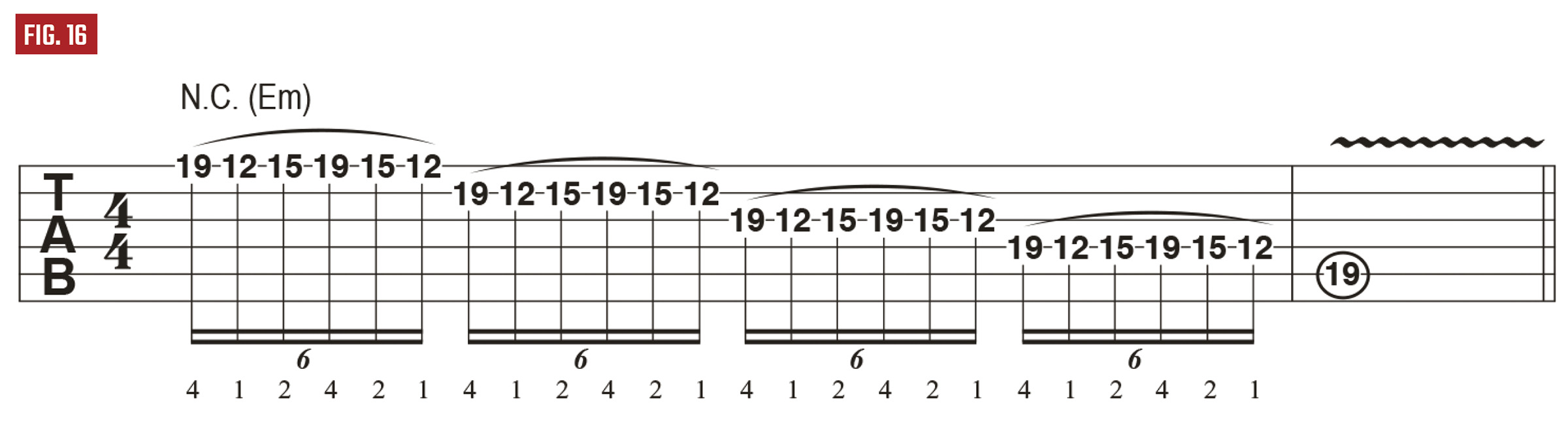

As I got to know my guitar neck better, I realized that there was an E note at the 19th fret on the A string – HOW ’BOUT THAT! Then, when I was jamming around one day, I thought to myself: “Hey I know some wide-stretch E minor licks (like the one in Figure 15) that also use the 19th fret, why don’t I try moving that fingering pattern idea across each string, from high to low, until I finish up on the E note at the 19th fret of the A string (Figure 16)?”

Since the fingering pattern in Figure 16 is exactly the same on each string, a lot of guys call this kind of thing a symmetrical run. It’s simple, but cool. To be honest, I have no idea what the hell scales this run uses because I’m not a cat that’s heavy on theory.

All I know is it sounds awkwardly cool in the key of E minor, and that’s all that matters. Listen closely and let your ears decide what notes are right or wrong! Anyway, because this idea worked, that’s how I got into futzing around with symmetrical runs in a major way.

Rut busting

Whenever you feel like you’re stuck in a playing rut, always try and remember two things: one, you ain’t the only player that gets hit with this shit; we all go through it from time to time. And two, you’re not always gonna be stuck there, so don’t freak out!

The only way that’ll happen is if you let it. So don’t get bummed out and go, “Fuck it, I quit!” That’s a dumb-assed, loser attitude. Instead, get to work, man. If you want to get out of a rut bad enough, you will. But it’s up to you. No-one else is ever gonna do it for you.

Fatherly advice

One day, when I was learning to play guitar, I was stomping around the house all pissed off because my playing was in a bit of a rut. My dad, who’s a great guitarist, said something that I’ve always remembered.

He asked me, “can you learn a new lick today?” I said, “of course I can.” Then he said, “well son, if you decided to learn just one new lick a day, how many would you have at the end of the year?”

Think about it, man! The possibilities are staggering. Shit! If I knew a lick for every beer or Black Tooth I’ve had, I can’t even imagine how much extra knowledge I’d have!

The importance of others

To me, a sure-fire way to get into a rut is to sit around and play by yourself all the time. You’ve gotta get out there and jam! You don’t have to necessarily be in a band. All you need is a couple of buddies who play.

And they don’t have to be guitarists either, jamming with a bassist or a drummer is cool. Jamming with other people creates energy and excitement. You can feed off that, and it will help push you to do things you’d never dream of by yourself.

Be yourself, by yourself

If you have no buds to jam with, you can always record a rhythm part yourself and then wail a lead over it. I used to do that all the time. Don’t always jam over the same sort of stuff though, or you could fall into a rut.

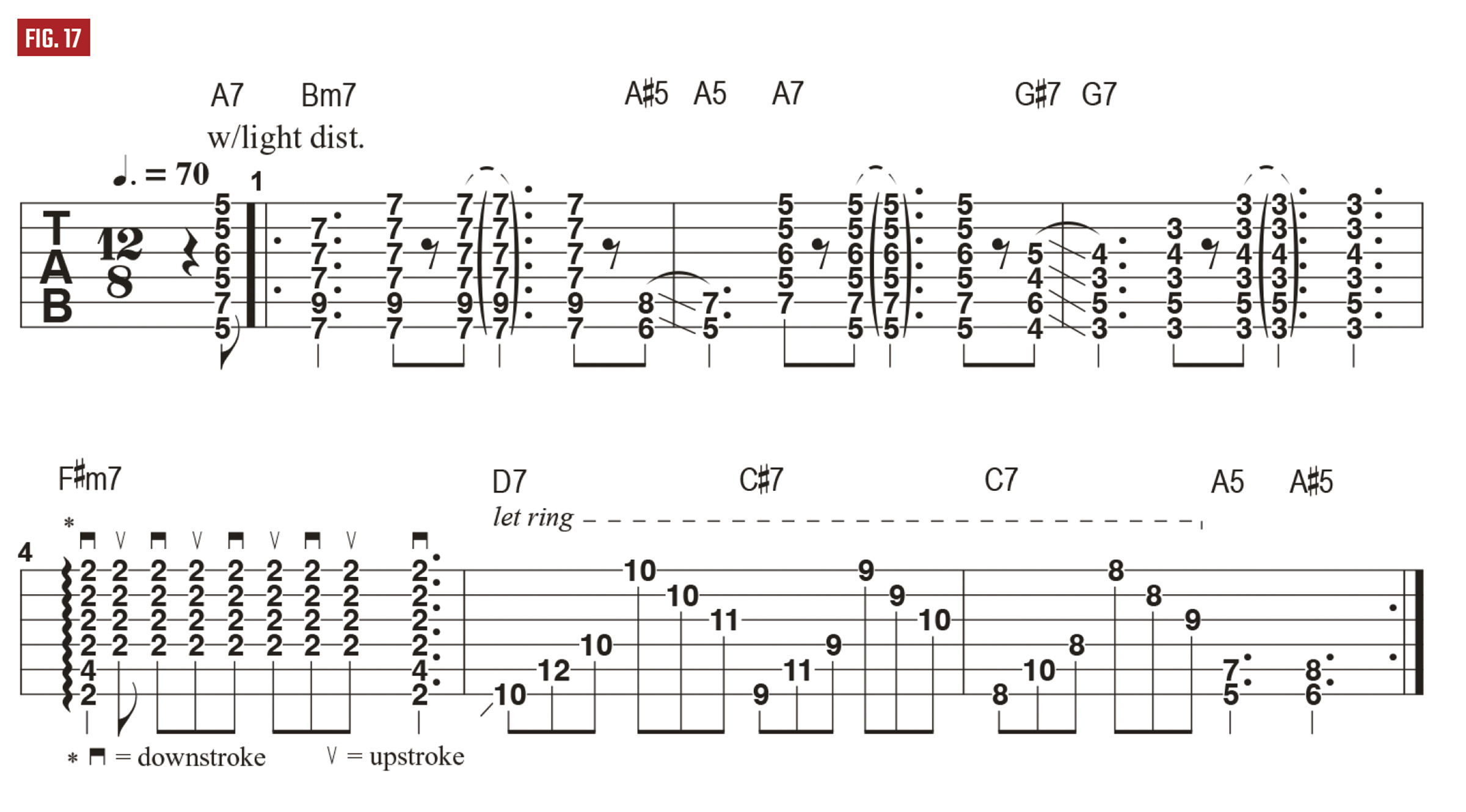

Whenever I’d get tired of soloing over heavy riffs in E, I’d come up with something in a completely different key that had a completely different feel to it. Sometimes a change of mood and key can help you find fresh lead ideas. This laid-back, bluesy B minor riff in Figure 17 is a good example of what I’m talking about here.

Signing off

Hopefully I’ve helped open some ears and eyes! Let all the ideas I’ve put in your heads come as they will – subconsciously and naturally. And remember. It’s all good; everything goes; and there ain’t no damned rules nor boundaries. So, get off! Tear it a fresh ass. Tear it hard. Rip gaping holes in it. Make tracks – leave marks!!!

Forever, Stronger Than All.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“There are so many sounds to be discovered when you get away from using a pick”: Jared James Nichols shows you how to add “snap, crackle and pop” to your playing with banjo rolls and string snaps

How to find new approaches to blues soloing – using fingerstyle improv ideas and Roy Buchanan-inspired licks

![Pantera - Cowboys From Hell (Official Music Video) [4K Remaster] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/i97OkCXwotE/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)