Feel like your solos don’t quite sing? The key is using the right articulations to make your guitar “speak” to audiences

Andy Wood walks us through some strategies for making your guitar truly sing

I started out primarily as a bluegrass mandolin player, an endeavor for which Olympian levels of flatpicking are often required to perform the melodies and solos you will hear from great mandolin players like Sam Bush, Bill Monroe and David Grisman.

When I switched to guitar, I worked hard to keep my alternate/flatpicking technique up to speed, and I also started using hybrid-picking techniques associated with country guitar while also incorporating various “rock” articulations, such as hammer-ons and pull-offs, and also using double-stops (two-note chords) and finger vibratos.

I find that doing this enables me to expand my musical vocabulary and “speak” on the instrument in a variety of appealing ways.

In the previous two columns, I offered examples of ways to bolster your flatpicking technique via the relentless alternate picking required to play my song Free Range Chicken (Charisma).

In this column, I’d like to reference additional parts of the tune to illustrate more cool and useful techniques.

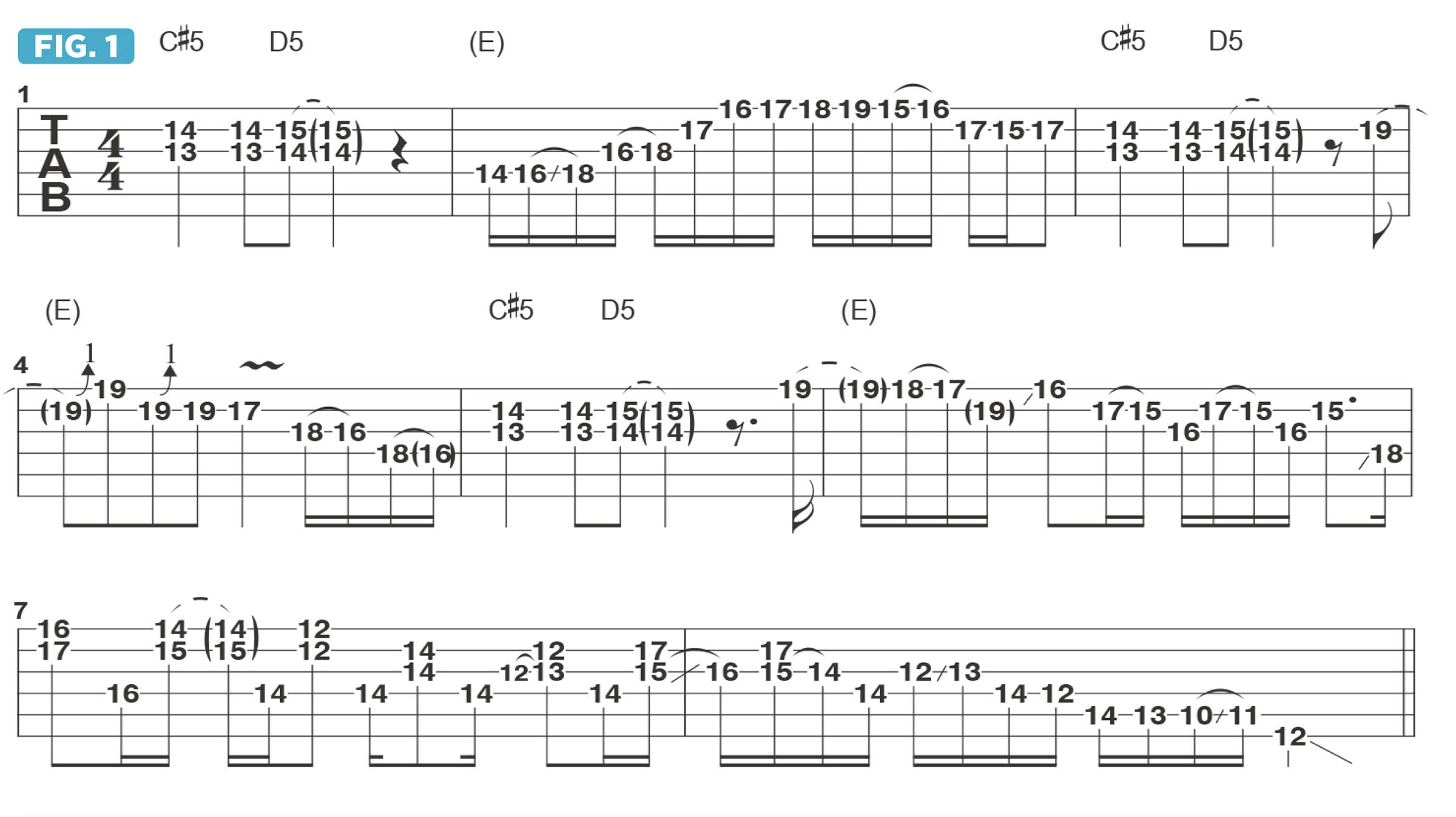

Figure 1 illustrates the eight-bar verse tag, which starts with two-note, root-5th C#5 and D5 double-stops. These reoccur in bars 3 and 5. In bars 2, 4 and 6-8, I play a series of melodic phrases, each of which is articulated in a slightly different manner.

Before we get to the phrases, I’d like to point out that, harmonically, I like to take a “global” look at the tune. All of these lines revolve around the chord tones of E7– E, G#, B, D – and I envision them on the fretboard across a three-octave span.

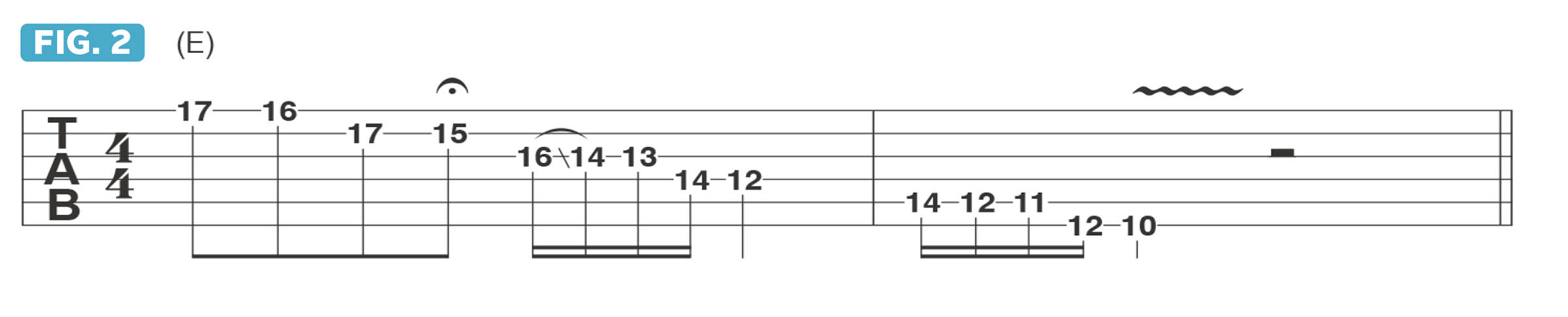

If I add the 4th, A, to the mix, the notes are E, G#, A, B and D. Figure 2 shows this row of notes descending across three octaves.

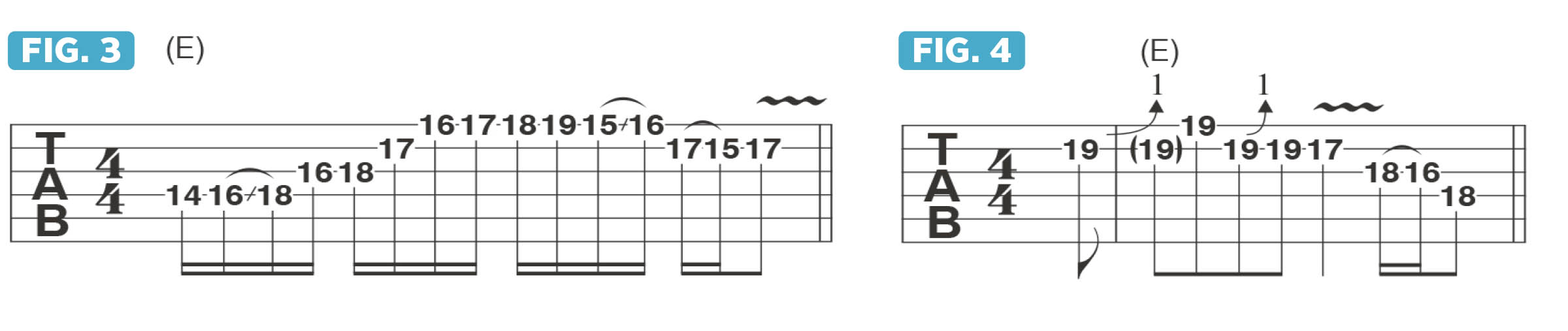

The first “lick,” shown in bar 2 of Figure 1 and zeroed-in on in Figure 3, begins on the E root note, moves up through the E major pentatonic scale (E, F#, G#, B, C#) then incorporates some chromaticism (consecutive notes half steps apart) on beat 2 into beat 3.

I learned many licks like these from studying bluegrass fiddle tunes, where it’s common to combine major pentatonic lines with chromatic passing tones, such as the move from the minor 3rd, G, to the major 3rd, G#, at the end of the phrase.

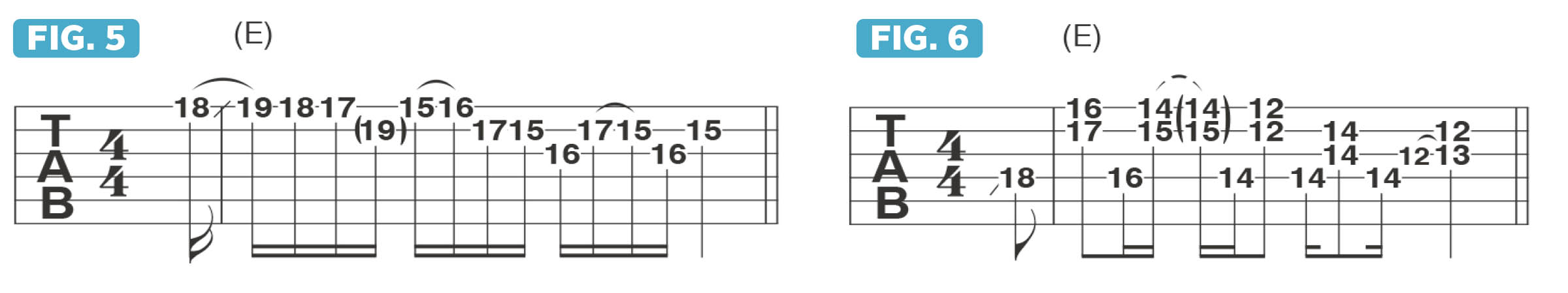

The next “lick” that follows C#5-D5, shown in bar 4 of Figure 1 and focused on in Figure 4, is a Leslie West-inspired phrase articulated with bends and wide vibratos, a la Mountain’s Mississippi Queen.

Bar 6 of Figure 1, broken down in Figure 5, is one that’s all over my Junktown album and is a mandolin-style lick that you’ll hear in the playing of Sam Bush and David Grisman. I begin with a slide from the flatted 5th, Bb, up to the 5th, B, then descend to Bb and A, followed by G to G#.

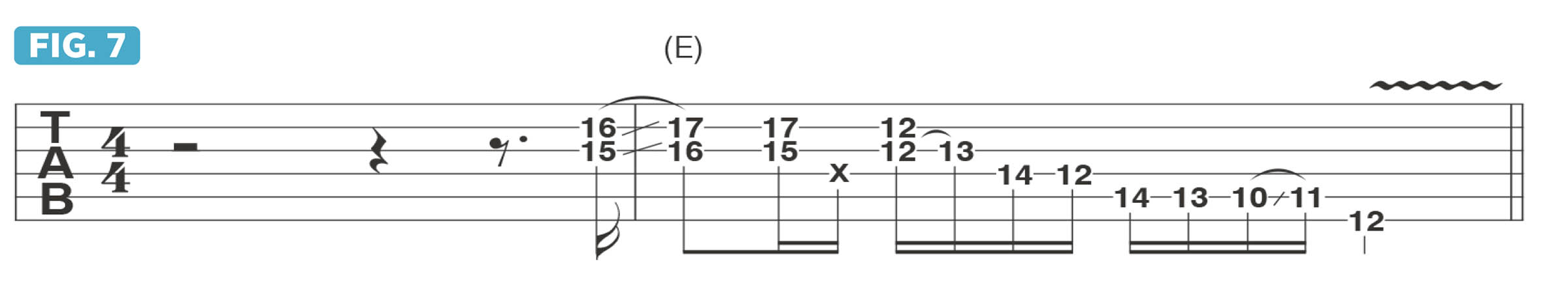

The section ends with lines that include various hybrid-picked double-stops, as shown in bars 7 and 8 of Figure 1 and in Figures 6 and 7: all of the double-stops here are intervals of either a 3rd or a 4th.

The section concludes in Figure 7 with a descending lick based on the E blues scale (E, G, A, Bb, B, D).

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

![Joe Bonamassa [left] wears a deep blue suit and polka-dotted shirt and plays his green refin Strat; the late Irish blues legend Rory Gallagher [right] screams and inflicts some punishment on his heavily worn number one Stratocaster.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/cw28h7UBcTVfTLs7p7eiLe.jpg)