What are 6/9 chords? Meet 5 chord shapes that make perfect set closers – and murder mystery soundtracks

6/9 chords have a sound like no other, and their evocative voicing has made them a favorite of Brian Setzer. But they can be ominous, too…

Sometimes, when music theory ties us in knots, it’s good to remember that so much of what we’re dealing with is just names for sounds. And sometimes those names struggle to keep up with the complexities of music as much as we do!

One term that can throw people at first is the 6/9 chord, so this feature will attempt to dispel any mystery about them and their possible variants.

As you might suspect, the 6/9 chord contains both the 6th and the 9th of the ‘parent’ scale, the scale the chord is taken from. In practice, the name 6/9 is actually an abbreviation of 6add9 because 9th chords would technically contain the 7th.

They have a very particular sound due to the stacking of 4ths. Check out the C6/9 in Example 1, which, apart from the root (C), consists entirely of 4ths, the remainder of the chord being E, A, D and G – the same as the bottom four strings of the guitar!

See below for a few useful major and minor 6/9 voicings, plus an extra twist here and there.

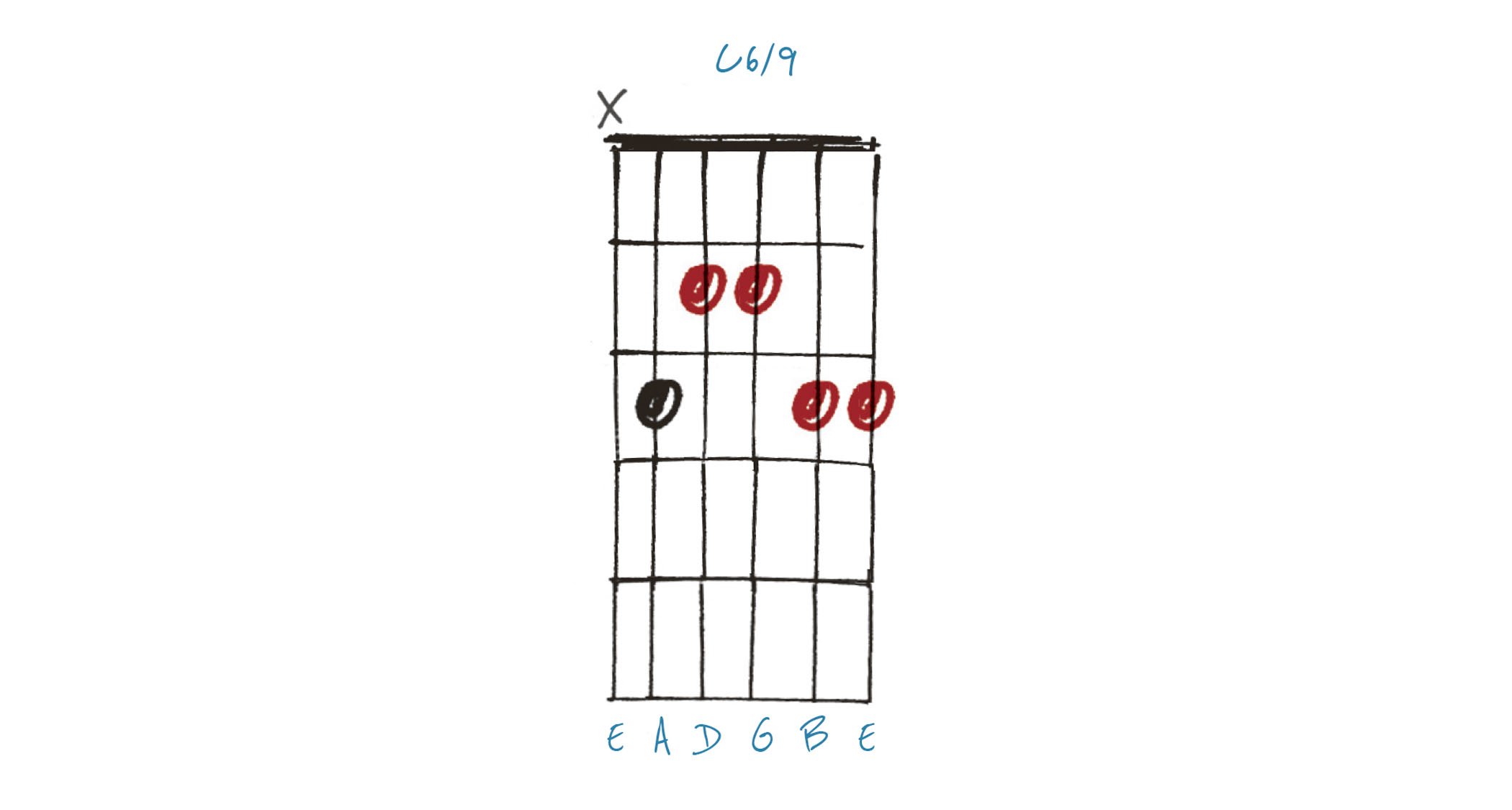

Example 1. C6/9

This C6/9 is movable to any key, preserving the stacking of notes with the root on the bottom and stacked 4ths on top.

This makes a great substitute for a regular major chord if you’re looking to jazz things up, or move the E on the fourth string down a semitone to Eb for Cm6/9.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

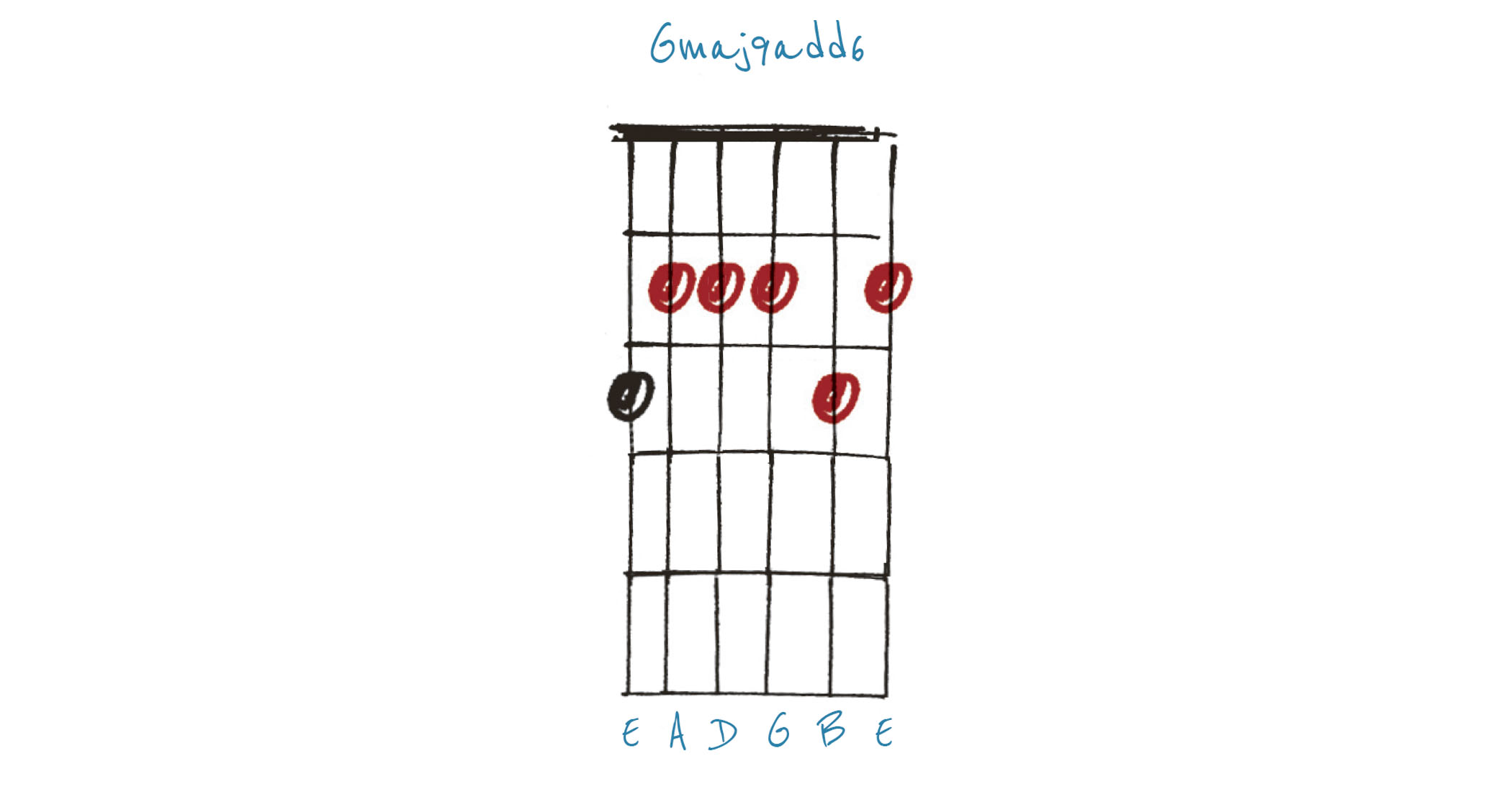

Example 2. Gmaj9add6

Basically moving a similar shape across to have the root on the sixth string, this sounds very much like a G6/9 – but the presence of the maj7 (F#) on the first string changes the naming convention.

Theoretically, this is first and foremost a Gmaj9 but with the 6th added. So we have Gmaj9add6, but we can view it as a ‘deluxe’ version of G6/9.

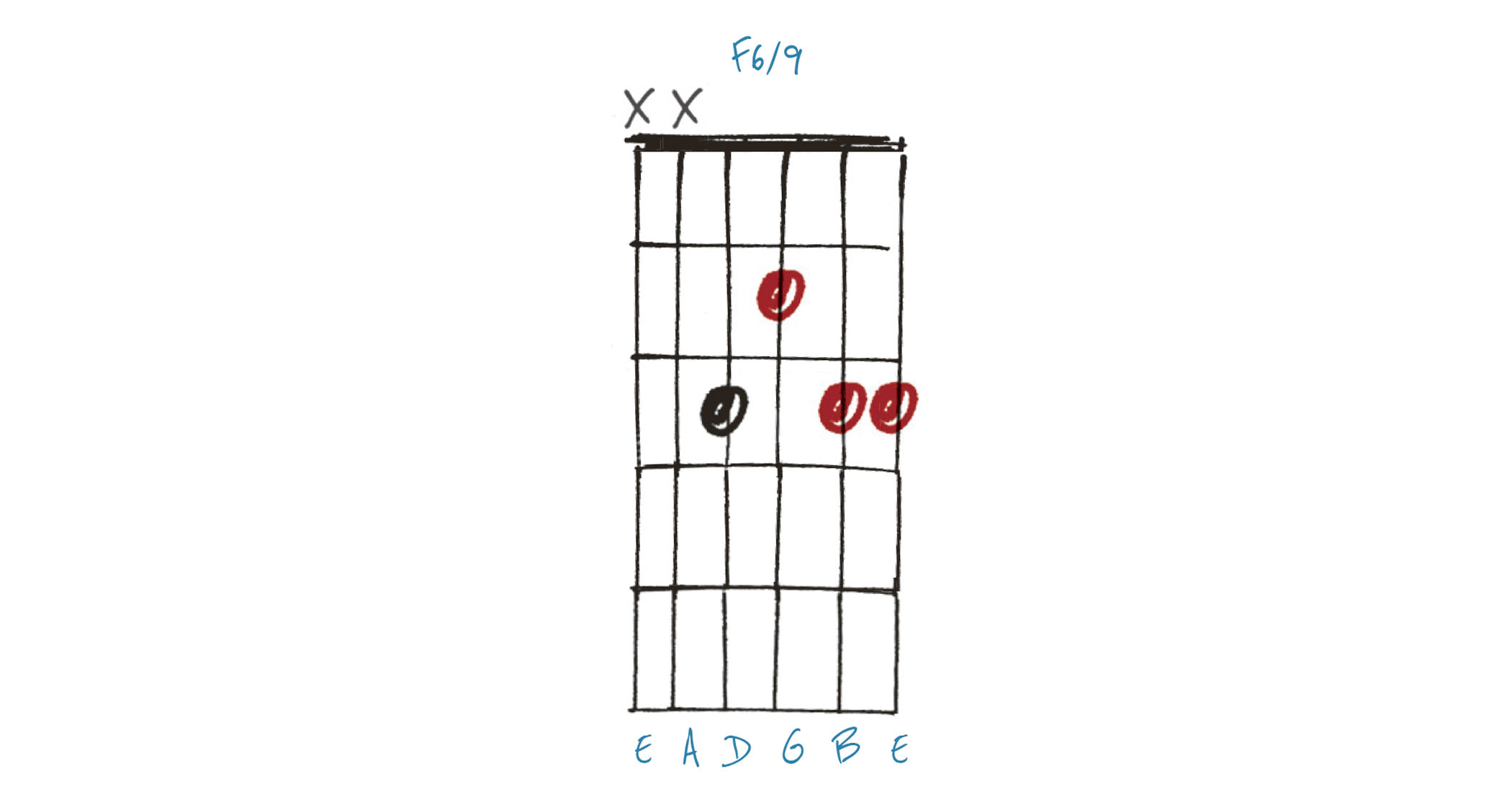

Example 3. F6/9

This small but beautiful F6/9 is movable to any key, like Examples 1 and 2. From low to high it stacks up as: root (F), major 3rd (A), 6th (D) and 9th (G), omitting the 5th – as so many jazz-flavoured voicings do – and getting straight to the point.

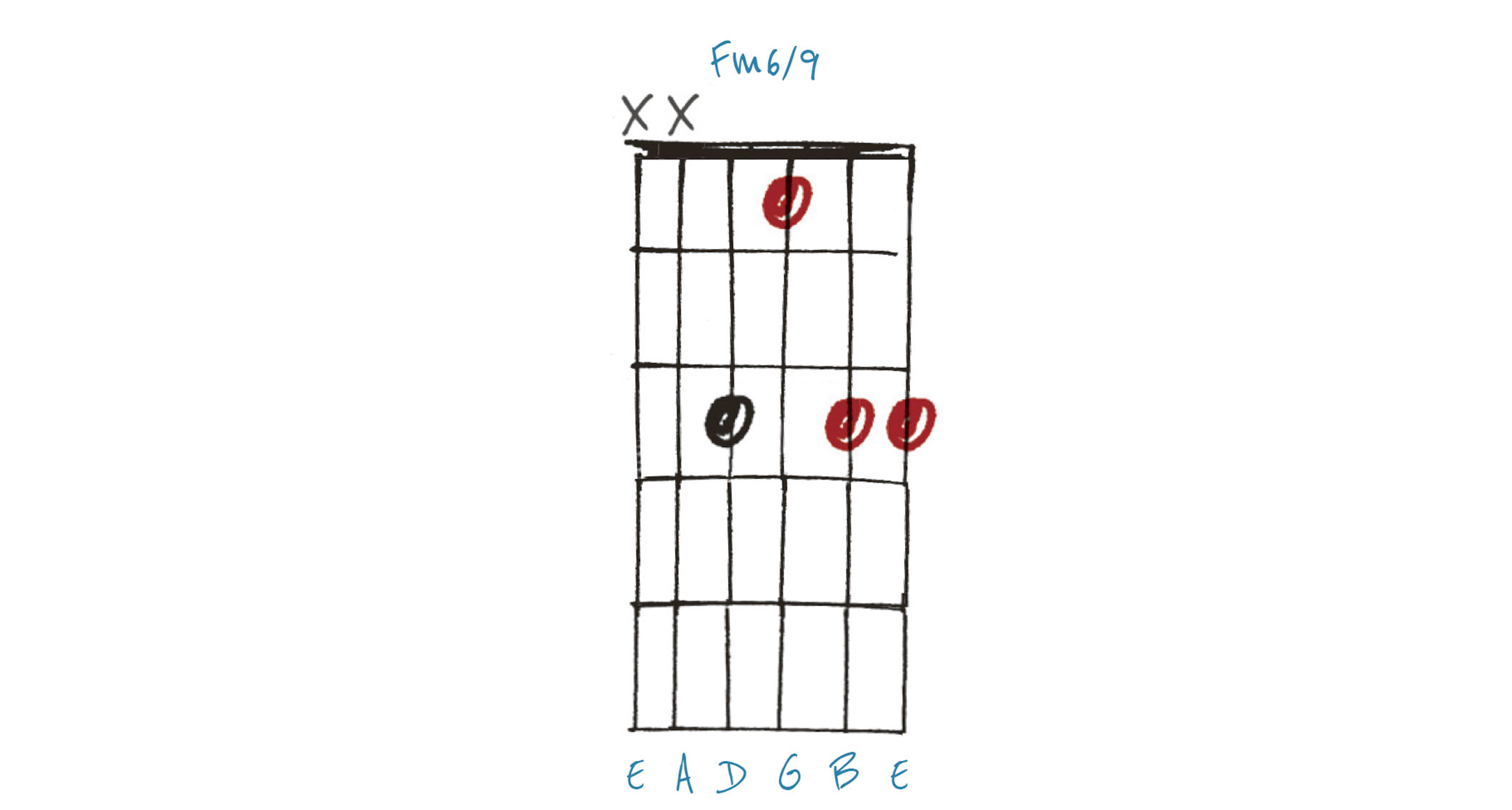

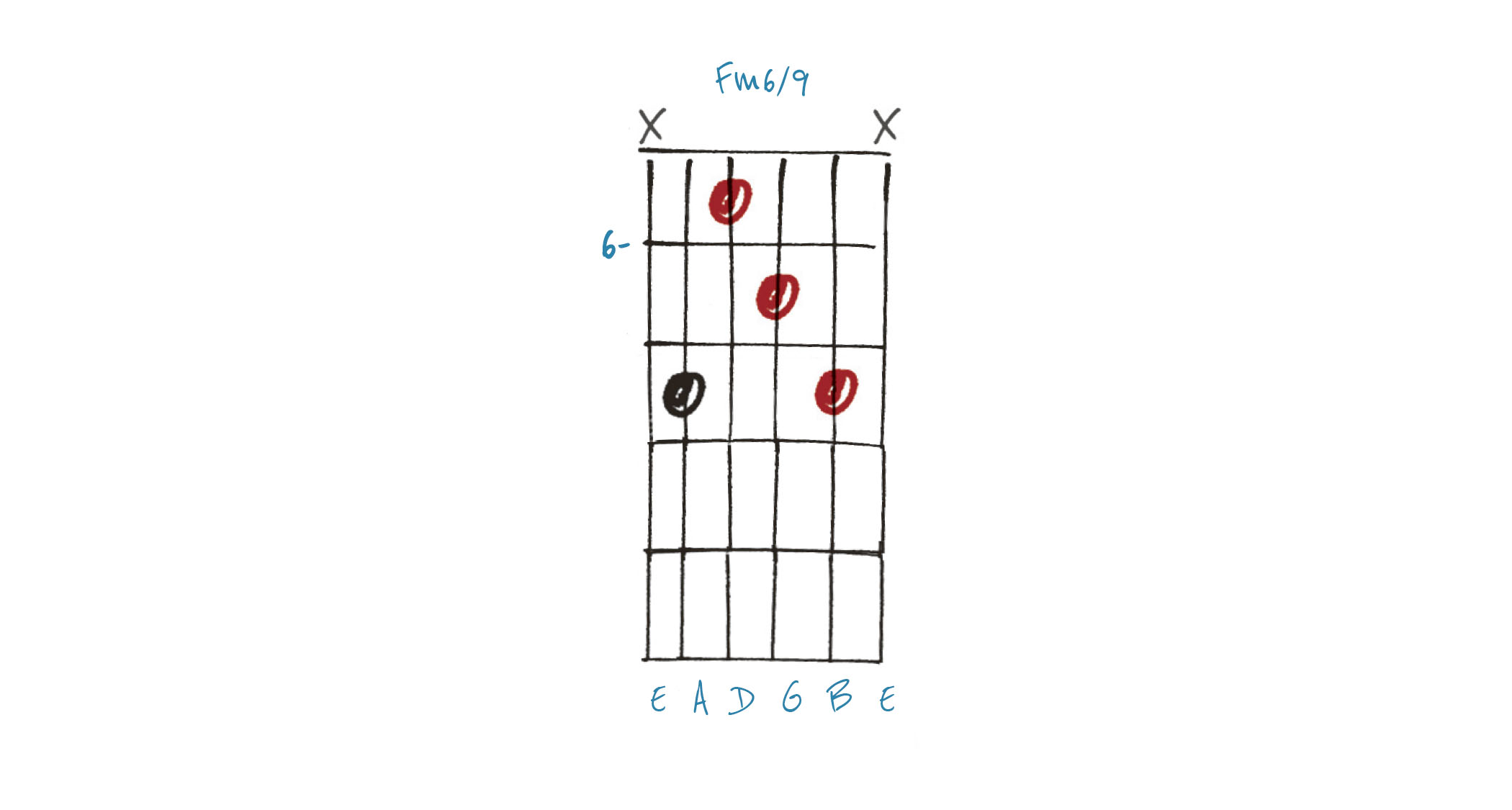

Example 4. Fm6/9

A minor version of Example 3, this Fm6/9 calls to mind Brian Setzer’s dramatic ending to Stray Cat Strut (though that’s in C, it’s easy to shift key). As we shall see in Example 5, you can achieve a darker sound by transposing this voicing over to the lower strings.

Example 5. Fm6/9

This version of Fm6/9 is identical in its intervallic structure to Example 4, but it gains a darker sound by being played on the thicker strings.

You can add a mysterious ‘murder mystery’ quality to this by adding in the maj7th (E) via the open first string, which would be an Fm/maj9add6.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.