Thrash Producers: The Sound And The Fury

In the mid Eighties, metal and punk merged into a fractious fusion of riffing and rage that lives on in today’s music subculture. Guitar World talks to the producers who crafted the sound on groundbreaking albums by Megadeth, Anthrax, Possessed, Death and other bands from extreme metal’s formative years.

When the music of the Eighties comes to mind, people often think of hair bands and one-hit-wonder new wave groups. In fact, the mid-to-late Eighties was a hotbed for the evolution of metal and punk music. Both genres were born in the Seventies, but it was during the Eighties that they morphed into hardcore, speed/thrash/death metal and numerous other genres and subgenres, spawning the diverse scene that typifies metal and punk in the first decade of the 21st century.

In the mid Eighties, for every Metallica that led the charge there existed innumerable smaller, if not more interesting, bands trying to get their music out into the world. There were also several go-to guys working behind the scenes who understood the music and knew how to record it right—guys like Randy Burns (Megadeth), Scott Burns (Sepultura), Casey McMackin (Randy Burns’ engineer), Alex Perialas (Anthrax) and Colin Richardson (Carcass, Machine Head). Anyone who wants to understand why extreme metal sounds the way it does today needs to start here, with the men who shaped the sound of the music heard on countless metal- and punk-influenced records. In this Guitar World exclusive, each producer and engineer speaks for the first time about his career and tracks the development of metal- and punk-based music from the Eighties to today.

If you were a thrash/speed/death metal fan back in the Eighties, you saw the names Randy Burns and Casey McMackin on the back of a lot of albums, including releases by the Crumbsuckers, Dark Angel and Megadeth, to name just a few. Burns usually produced, while McMackin engineered. Their partnership was born on what is among the most defining albums of Eighties metal: the Megadeth classic Peace Sells…But Who’s Buying?

1981 punk compilation Hell Comes to Your House, produced by Randy Burns

Before their merger, Burns played guitar in bands and had a little home studio. He wasn’t looking to be a producer, but as a favor he recorded a neighbor’s punk band. Soon, word got around that Randy Burns knew what he was doing. His next assignment was in 1981 as the engineer on a punk compilation called Hell Comes to Your House (the album reportedly cost $550 to make and featured Social Distortion, among many other L.A. punk bands). Burns’ production work on Hell got him another engineering gig, the self-titled 1983 debut from Suicidal Tendencies. The band had just added guitarist Grant Estes, who had long hair and played a Les Paul through a Marshall—characteristics that even then had been long associated with rock and roll. On Suicidal Tendencies classic track “Institutionalized,” Estes soloed throughout, making for an even more unconventional approach to punk.

“Suicidal were venturing away from what was traditionally considered okay to do in punk rock,” says Burns. “There were some really straightforward fast and simple punk songs on there, but they were also moving in a different direction. They really did merge some of the qualities of heavy metal and bringing that into the punk thing. Punk started going less garage and toward more of a produced sound.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The song “Institutionalized” would also became an unlikely alternative radio hit. Burns never thought about whether the song had any airplay potential. “I was just desperately trying to get the product out in this ridiculously short amount of time,” he says. The first Suicidal album had a $2,500 budget and was completed in four separate eight-hour sessions.

Burns loved the fact that punk and metal were starting to come together and saw no reason why it shouldn’t happen. “I always found sticking people in these musical pigeonholes really ridiculous,” he says. “There were people in punk bands that would literally say to me, ‘We can’t do that, that’s too heavy metal.’ But it seemed pretty clear to me that those two worlds were merging in a big way, and I was kinda right in the middle of that.”

Suicidal Tendencies' self-titled 1983 debut

Still, the walls separating punk and metal didn’t come down easily; neither side could get past the stereotypes and hear the music for what it was. Metal was bloated with Spinal Tap–like clichés, and the punks resented metalheads trying to infiltrate their scene. At the same time, those who didn’t understand punk in those early days dismissed it as a bunch of noise—a joke perpetrated by people who couldn’t play their instruments.

One day Burns was contacted by Steve Sinclair, who produced the Hell Comes to Your House compilation and had since moved over to the indie metal label Combat Records. He wanted Burns to produce the 1985 debut album, Seven Churches, from the San Francisco band Possessed.

Possessed were one of the first American death metal bands, and they set the template for innumerable bands to follow. Jeff Becerra, Possessed’s lead vocalist and bassist, was also the inventor of the term “death metal;” he reportedly came up with in his high school English class, and the phrase became the title for the group’s 1984 demo. (So young were Possessed’s members that lead guitarist Larry LaLonde, later in Primus, was still in high school at the time Seven Churches was recorded.)

The album was recorded at Prairie Sun Studios in Northern California, which also had a chicken ranch on the grounds. In the book Choosing Death, a history of death metal and grindcore written by Albert Mudrian and published in 2004, Beccera recalled every time the band blasted out their music, the chickens fled in terror. “We got some complaints about disturbing the farm animals!” Burns recalls with a laugh. Seven Churches, was recorded in a week for $10,000, a typical budget at that time for a Combat band.

Possessed's debut, Seven Churches

Although a lot of heavy bands came from San Francisco, the Bay Area thrashers didn’t know what to make of Possessed at first. The group became very popular overseas from tape trading and was even dubbed “the San Francisco Slayer” by some fans, but back at home it took a while for Possessed to catch on. A lot of Burns’ production peers also couldn’t understand why he worked with the bands he did, but Burn was one of the few who clearly understood where his groups were coming from. “I think it really helps if you’re a fan,” he says. “You have to appreciate something about what they’re doing. It’s a lot more fun if you like ’em, I’ll put it that way.”

Burns always took a “documentary” approach with the bands he worked with: “I used to tell them that the record will sound exactly like them, only better than they’ve ever imagined. I didn’t go in and say, ‘You guys need to rewrite this song.’ I think the reason why bands liked me is I assumed they knew where they were going with this stuff, my job was to figure it out. What are they trying to do? What is the band trying to say? And how do we get that? So I don’t think I was responsible for the success of Possessed. That was them; that’s what they did. What I did was facilitate getting it to tape.”

Smart producers always pay attention to gear, and if a band had equipment issues, Burns would deal with them ahead of time. If someone’s amp didn’t cut it, he’d rent modified Marshalls from Michael Soldano, who was just starting out in L.A. before launching his own amp line. If a drummer needed a better kit, Burns often went to the Drum Doctor, a local percussion rental service.

Yet the secret to getting brutal sounds on record wasn’t rocket science. Burns put the most emphasis on the band’s performance. First he’d try to get the bass and drums live. “If there were little imperfections in the drums, I figured we could live with them. As long as they had a really good feel on the drum and bass tracks, then I’d go with that.”

Burns wanted to make the guitars wrap around the rhythm section instead of the other way around. Once the bass and drums were laid down, the guitarist had to perform two tracks of guitar as tight and clean and precise as possible. If mistakes were allowed for the drums and bass, Burns wouldn’t let anything slide when recording the guitar tracks. “I would really beat up on the guitarist and make ’em play the whole thing right,” he says. “Speed metal really has to be tight. It takes time and it’s very tedious, but if you get it right, it will jump off the speakers at you.

“My biggest problem was always making the guitars too loud, but that’s the way people like them. If you’re gonna make a mistake, making the guitars too loud probably isn’t the worst one to make.”

Yet the insights and experiences Burns gained working with the heaviest bands of the time almost never happened. Not long after working with Possessed, he dropped out of the music business and began studying computer science at a local school. Then he got another call from Steve Sinclair: “Randy, you’re the only guy I can trust with this band. You have to do this.”

At Sinclair’s urging, Burns went down to SIR studios in Hollywood, where he saw Megadeth rehearsing what would become their 1986 sophomore album, Peace Sells…But Who’s Buying? Burns’ hiatus from the music business was over then and there. When working with bands, Burns never predicted an album would be a hit, but with Megadeth he says, “I knew right then it would be a hit record. I was just blown away.”

Megadeth's 1986 sophomore album, Peace Sells…But Who’s Buying?

Because Combat had high expectations for Megadeth’s next album, the label gave the band a bigger recording budget than the average thrash band (recording and mixing ultimately cost $22,500). Peace Sells was recorded at the Music Grinder, a now-defunct studio that was located on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. It was the primary studio where Burns produced most of the bands on his résumé, and it’s also where he forged a strong partnership with Casey McMackin.

McMackin had begun working at the Music Grinder as a gofer. He had some previous schooling but learned engineering by observing and listening to what was going on around him. Peace Sells was the first album McMackin ever engineered, and Burns says, “Casey should get a lot of credit for that album.”

The most fun song to record was Megadeth’s cover of the Willie Dixon blues classic “I Ain’t Superstitious.” Burns often liked to lay down the bass and drum tracks at the Grinder, then go around to smaller studios in Hollywood and pay $25 to $30 an hour to overdub guitars and vocals. Poland laid down his solos in several different studios and told McMackin, “I like the beginning of this solo from this studio, but I like the second phrase from this studio and this phrase from this one…”

McMackin was against cutting the licks together. As he told Poland at the time, “The sound’s not gonna match,” but Poland didn’t care. Following the guitarist’s instructions McMackin cut the different takes together. To his pleasure, he found that the resulting compilation of takes gives Poland’s solos an effective call-and-response quality.

Peace Sells was released in the fall of 1986, when a number of great speed thrash albums seemingly all came out at once, including the big daddy of the genre, Slayer’s Reign in Blood. With the help of Burns and McMackin behind the boards, L.A.’s Dark Angel would also record their best album, Darkness Descends, which came out right after Reign in Blood and today remains a relentlessly brutal classic. Drummer Gene Hoglan, currently in Strapping Young Lad, was Dark Angel’s leader and he proved to be an intelligent lyricist as well. Hoglan loved to use a lot of big SAT words in his lyrics and a lot of speed/thrash bands at the time were also going thesaurus crazy when they got bored using the same old adjectives to describe something evil. Says McMackin, “I learned a lot of words from Gene.”

Dark Angel's Darkness Descends

Burns and McMackin also had a lot of fun working with a number of New York bands signed to Combat, including Nuclear Assault, the Crumbsuckers and Ludachrist, who later changed their name to Scatterbrain. The New York bands they produced had a healthy sense of humor in their music. Unlike the success-driven Mustaine, they primarily wanted to play and have a good time.

Yet for many New York bands, Alex Perialas was the go-to guy for heavy production. Perialas produced most of the bands on Megaforce, the indie label founded by John Zazula, who previously ran the New Jersey metal store Rock ’N’ Roll Heaven. Megaforce, of course, was Metallica’s label before they moved on to Elektra, and it was also home for Anthrax before they went to Island.

Then as now, Perialas worked out of Pyramid Sound studio in Ithaca, New York, and when the heavy new wave of American metal was just getting started in the mid Eighties, upstate New York was the place to be: Metallica had recorded Kill ’Em All at Music America Studios in Rochester, in 1983, and Anthrax were going to record their 1984 debut, Fistful of Metal, there as well.

“Music America was a social club in Rochester back in the Thirties,” Perialas recalls. “It was basically this big, empty, nasty building that needed a lot of work, and Anthrax were staying there. Paul Curcio, who produced Kill ’Em All and was going to produce Fistful of Metal, was supposed to get new equipment for the studio, but it didn’t arrive when Anthrax was slated to start, so they went on the prowl looking for studios in upstate New York. When they happened upon my place, I kinda knew the name Anthrax from the grapevine and the first thing they heard was that this studio could actually make something aggressive.”

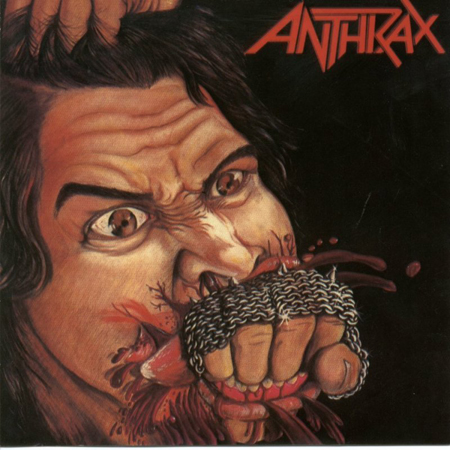

Anthrax's 1984 debut Fistful of Metal

Perialas was always a fan of heavy music, and he was excited to work in the brave new world of thrash/speed metal. “I was always interested in hard edged music growing up,” he says. “I listened to Priest, Maiden, Accept, harder edged, riff-driven bands.” At the time, riff-masters like James Hetfield and Scott Ian were introducing an even faster and tighter form of rhythm playing that blew Perialas away. “I had never really heard rhythm guitar quite like that before,” he says.

Like Burns, Perialas paid close attention to gear and looked into everything that made the sound. “We were into hearing the real girth of the strings and wanted to hear all the notes in the chord,” he says. “Pickup height was something we played around with a lot. We’d actually sit there and keep striking the chord and tweaking the height of the pickup until we found the right spot where the magnets affected the string.”

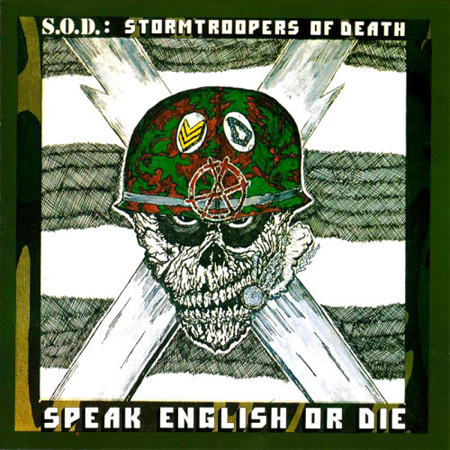

When Perialas worked with Anthrax, they used custom-made Jackson guitars. Scott Ian’s primary studio guitar was a Pearl White Randy Rhoads model with a single pickup, a Seymour Duncan JB model in the bridge and “NOT” painted in big blue letters on the body. Amps were Marshall JCM800s and JMPs, including some of the early JMPs from the Seventies. In fact, Perialas still has the Super Lead master volume JMP that Ian used on his infamous side-project, S.O.D.

Scott and drummer Charlie Benante were both big hardcore punk fans and attended numerous weekend hardcore matinee shows at the legendary New York City club CBGB. After laying down his guitar tracks for their 1985 Spreading the Disease album, Ian was bored waiting for the rest of the record to be completed. With a lot of free time on his hands, he began to come up with crazy, intense riffs and short hardcore tunes. Perialas was duly impressed.

“We were putting the finishing touches on Spreading the Disease and I heard these riffs that Scott was messing around with,” Perialas recalls. “I said, ‘Man, those are sick.’ Johnny [Zazula] asked me what I thought, and I said, ‘This is crazy, we need to make this record.’ He told us to go ahead, and he said, ‘You gotta do it in three days, though. That’s all I’m gonna pay for.’

S.O.D.'s Speak English or Die

“So we just fired up and worked around the clock. I’ll never forget I was mixing that record in the control room and everybody was on the floor passed out. In those days, there were no budgets, so we were always under time constraints, the pressure of the label and the wrath of Johnny!”

The finished product, Speak English or Die, which also came out in 1985, was a landmark crossover album that further bridged the worlds of hardcore punk and metal. More than 22 years after its initial release Perialas says, “That album still has that energy to it that makes you want to break stuff. It was a statement that stands to this day.”

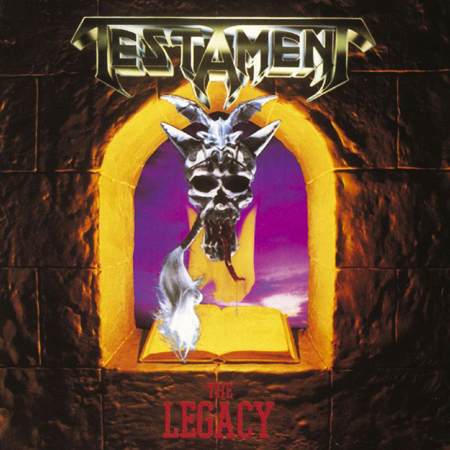

Although the thrash/speed metal scene peaked in 1986, great albums were still being released in 1987, including Anthrax’s Among the Living and Testament’s debut, The Legacy. Perialas was turned on to Testament by Megaforce staffer Metal Maria Ferrero, who was Johnny Zazula’s girl Friday. “Maria was really a huge champion of that project,” Perialas says. “The minute I heard them I said, ‘I need to make a record with this band.’ ”

Perialas loved working with Testament’s guitar team of Eric Peterson and lead guitarist Alex Skolnick, who was just out of high school when the band recorded The Legacy. When recording his solos, Skolnick “had such a great grasp of the instrument that you could do six takes with him, and all six would have a common thread, but each one of them would be brilliant in its own way. So it was just a matter of steering his young energy.”

Testament's 1987 album The Legacy

That year also saw the release of another crucial album in the death metal genre produced and engineered by Burns and McMackin: Death’s Scream Bloody Gore, which again was released through Combat. Burns has fond memories of working with Chuck Schuldiner, the late founder of Death. “I thought Death took it to another level,” he says. “They were definitely groundbreaking, and I really liked Chuck’s guitar playing. He was a lot of fun to work with. He was a real hard worker, and he was really efficient in the studio. He really took to it.”

Many death metal bands love to scream between verses, and on one track, Schuldiner let loose a blood curdling scream that lasted about 30 seconds. Everyone liked it, but Burns knew Chuck could do better. Schuldiner screamed again, and the effect was even better. Burns, however, wanted to see if Chuck could push it even further.

Death's Scream Bloody Gore

“The third scream comes by and it was crazy,” McMackin says. “ ‘If we can do better, let’s just do one more.’ So I’m rolling tape, I punch in to record, there’s no scream. I roll back again, punch in record, there’s no scream. We go running into the room, and Chuck had passed out from the scream. That’s dedication.”

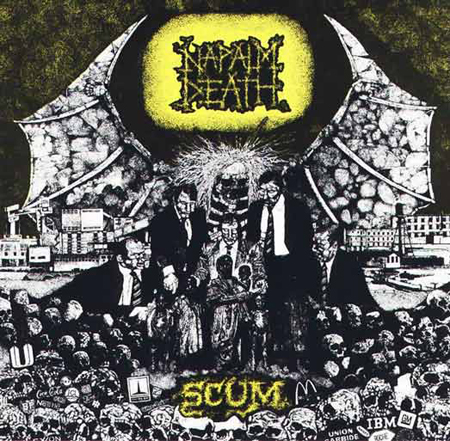

The year 1987 would also see the album debut of Napalm Death. Released through the British indie label Earache, Scum put Napalm Death on the map and established grindcore, a genre that pushed the envelope for speed and brutality like nothing before it. Early grindcore releases weren’t known for great production; that everything sounded so noisy and frenzied was initially part of its charm. Yet there was one producer who understood where the sound was coming from and was able to give it more clarity without stripping away its brutality.

Napalm Death's 1987 debut Scum

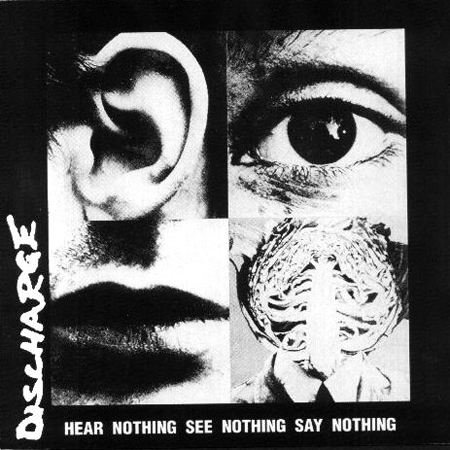

Colin Richardson started out as a gopher at a studio in his hometown of Manchester England. His first engineering experience was with the U.K. hardcore band Discharge on their legendary 1982 album Hear Nothing, See Nothing, Say Nothing, the influence of which could be heard in many speed/thrash metal bands that followed. As Scott Ian put it, “There was just a level of brutality on that record that I had never heard before. I could list 15 bands that if it wasn’t for that record wouldn’t even be bands, including Anthrax.”

Discharge's 1982 album Hear Nothing, See Nothing, Say Nothing

Richardson recalls being left on his own to mix the album. “I really wasn’t quite sure what I was doing back in those days. I was just trying to find out how everything worked. I remember putting the guitars through the studio graphic EQ because I didn’t think they were quite as full sounding in the tracking. I hadn’t recorded a guitar sound like that, so I just tried to get something together that was pleasing to my ear.”

The grindcore bands like Richardson’s work enough for Earache to make him a full-fledged producer. The recording process with bands like Napalm and Carcass was pretty much trial and error. “I was pushing myself and kind of learning with the bands,” Richardson says. “There was a nice naivete about it.”

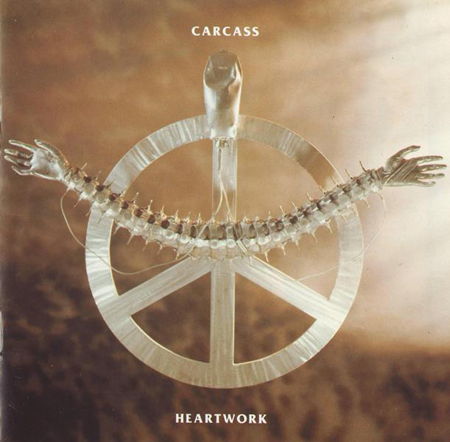

Richardson didn’t even start experimenting with changing pickups or using other amps besides Marshalls until ’93 or ’94, when Carcass switched to Peavey 5150s. “If you were a metal band, it was like, Okay, you use Marshalls. I know Pantera used Randalls, but I don’t remember any British bands having any kind of access to that.”

In fact, Pantera’s razor-sharp production was a big influence on Carcass when they went in a more melodic direction with their Heartwork album, which was released in 1994. Carcass guitarist Bill Steer brought a copy of Pantera’s Vulgar Display of Power to Colin and told him, “We want to get our own sound, but we really like the clarity on the guitar and the punch on the drums.” While laying down the Heartwork album, Richardson and Steer would compare/contrast a Carcass track to a Pantera song to try and capture the same clarity and precision.

Richardson says the death/grind bands he worked with weren’t resistant to trying new technology. The albums that were coming out of Morrisound Studios in Florida produced by Scott Burns had already inspired them to go for cleaner, more professional-sounding recordings.

Carcass' Heartwork

Burns (no relation to Randy) brought the first band he produced to Morrisound Studios in Tampa, Florida, in the early Eighties because it was the best studio he could find in the area, and a lot of local death metal bands went to the studio for the same reason. Morrisound specialized in high-tech production because, as Burns explains, the studio’s founders Jim and Tom Morris “were very progressive. They were very much into cutting-edge technology and buying good equipment.”

Burns engineered Death’s second album, Leprosy, which was released in 1988, and he helped complete Obituary’s 1989 debut, Slowly We Rot, when their original producer had to leave the project. Burns finally got his first big producing credit, Sepultura’s Beneath the Remains, by default.

“Roadrunner asked all the big producers,” Burns says. “They were all like, ‘This is death metal, this is shit.’ At the time, the death metal thing was kind of poo-pooed. All the thrashy, Anthrax-y kind of stuff was real popular and death metal wasn’t really taken seriously. I was Roadrunner’s last choice to produce the band.”

Burns produced Beneath in Sepultura’s home land, Brazil, in December 1988, and by the time he got back to the States in early 1989, the tides for heavy music finally started to turn. Like the peak of thrash in ’86, a lot of great death metal albums all seemingly came out at once from bands that included Carcass, Entombed, Morbid Angel and countless others. “It was a peak period for all the bands,” Burns says. “It was a big scene and it was a great time.”

Although death metal finally broke out of the underground, it eventually became clear it would never get to Metallica levels of success. “It was just too heavy for the average listener,” Scott continues. “It became apparent that this was as big as it was going to get and there’s nothing wrong with that, but it would never have mass commercial appeal.”

Sepultura's Beneath the Remains

And eventually, many producers who specialized in working with heavy bands found themselves pigeonholed. Both Randy and Scott Burns have left their producing days behind them and now work in computer programming. “In the end I wanted to venture out,” Randy Burns says. “I preferred it when I had more variety, but that’s the way it goes.”

Yet looking back on the bands he worked with, he is proud of what he accomplished. “I was really passionate about helping these guys get their music on tape,” he says. “This was such a huge part of their lives. Their music was so special to them, and to get the privilege of being there and help them do it, I was very passionate about it.”

Perialas also looks back on his days producing for Megaforce fondly. “The bands I worked with were really good kids and they were really serious about what they were doing,” he says. “None of those bands were partiers. They were really serious about trying to do good work, and I hope I instilled that in them.”

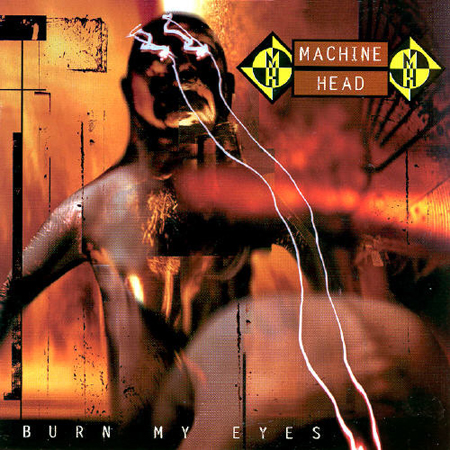

Machine Head’s debut Burn My Eyes

Richardson, on the other hand, is still actively producing and has worked across the heavy spectrum with bands as diverse as Bullet for My Valentine, Cradle of Filth, Funeral for a Friend, Slipknot and Trivium. Many younger bands want to work with him because of his work on Machine Head’s debut, Burn My Eyes.

“Burn My Eyes came out in 1994, so it’s amazing the longevity on that record,” Richardson says. “Bullet for My Valentine told me they listened to Burn My Eyes when they were kids and said that whenever they got a record deal, they were gonna remember who produced it and have that guy produce their album.”

“Around Vulgar, he would get frustrated with me because I couldn’t keep up with what he was doing, guitar-wise – Dime was so far beyond me musically”: Pantera producer Terry Date on how he captured Dimebag Darrell’s lightning in a bottle in the studio

“He ran home and came back with a grocery sack full of old, rusty pedals he had lying around his mom’s house”: Terry Date recalls Dimebag Darrell’s unconventional approach to tone in the studio

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)