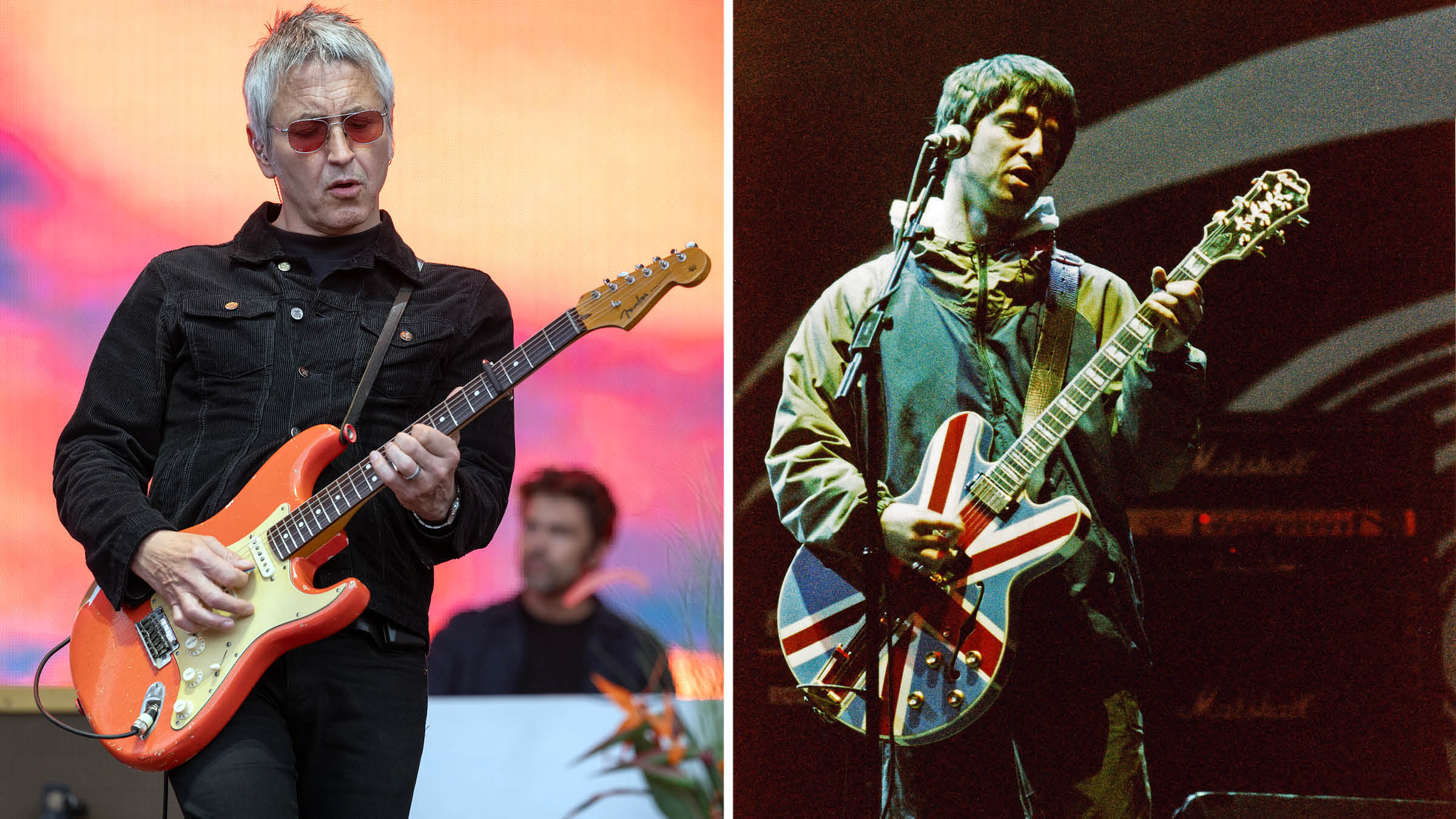

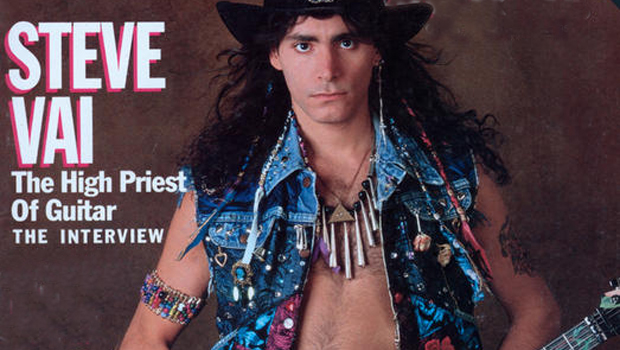

Steve Vai Discusses Recording 'Skyscraper,' His New Album with David Lee Roth in 1988 Guitar World Interview

Here's our interview with Steve Vai from the May 1988 issue of Guitar World. The original story started on page 50 and ran with the headline, "Zen and the Art of Steve Vai."

To see the complete Steve Vai cover -- and all the GW covers from 1988 -- click here.

It's two days before Christmas, and at Guitar World, the atmosphere is giddy. Ax slinger extraordinaire Steve Vai is coming to town, coming to these very offices, in fact, bearing a preview tape of Skyscraper, the album he's co-produced with David Lee Roth.

He and I have already filled in the general background part of the interview needed for this story, and now what's left is listening to the tape that's been entrusted to band members only (His managers are justifiably afraid that if they gave out any copies this far in advance they might surface on the radio) and hearing what he has to say about it, track by track.

So when he arrives, a kind of controlled pandemonium breaks out: Everybody wants to shake his hand, stop by and say "Hi," mention one of their favorite bits of his work and all that. Steve is his habitually gracious self, unselfconsciously poised, friendly, unflustered. In a phrase, in control even at his most relaxed, drawing a kind of strength from the exuberant near-chaos greeting him even when it threatens to sweep everything else before it.

Like how he plays guitar: never quite the expected lick in the expected place, never the feel, the tone, the cliché where almost anybody else would think it "belonged."

It's not because of his good looks or because he's such a nice guy that Steve Vai has risen to become one of the guitar's leading current practitioners.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Since his early teenaged lessons with Joe Satriani, his debut with Frank Zappa at the ripe old age of 19, through his own solo stuff, his fill-in time with Alcatrazz, his work with Ry Cooder on the movie Crossroads and now his role as co-producer and chief songwriter for multihued rock vaudevillian Roth, Vai has proven time and again that he's got some of the most wicked spins, some of the most outrageous chops in the land of the six-string.

And they're all his, payoffs for the years of hard work at his natural talents.

''I've never really heard anybody imitating anything of mine the way they do with Edward Van Halen's stuff," says Steve once the office has been cleared and the coffee's been brought and the chairs tilted back so we can listen and talk with our feet up on the editor-in-chief's cluttered deskful of manuscripts and memos. If that's true, and it seems to be -- it may be because how Steve Vai does what he does is less easily separable from what he does than Van Halen's techniques, like his overcloned two-handed tapping, are from his own musicality.

Where would-be Van Halens can master Eddie's gestures without absorbing the underlying intelligence at work partly because those gestures themselves are writ so large, anyone listening to Vai has to penetrate the carefully woven web of melodic and harmonic understanding, the off-kilter rhythmic flares, the restless and searching tonal variations and, of course, the emotional vibe that come together to spin out this ramified musician's vocabulary.

Articulate as Steve Vai is with his ax, so is he with his speech. That poise stays with him in the very different situations he's thrown into, providing him with a perspective that gives him needed distance on himself and those around him.

He talks, for instance, of his career in music and its development in a clear-eyed way that makes it plain he's looking to control how that development unfolds, that he's learned from past situations how to shape what he wants his future to be, where he wants it to go, as much as anyone can shape such things.

He avoids drugs like the plague, in part because they blur that intelligent distance. And if he wields his ax like a rampaging chainsaw killer, he's never committed random violence with it; he's always somehow found something striking and coherent to say in that idiosyncratic way that eludes any would-be imitators.

That idiosyncratic approach is the result of the path he's made for his life in music. Unlike a lot of young musicians, Vai has created and seized opportunities to present himself and what he does in a wide variety of contexts.

Partly, that open-ended sense of determination is driven by a Zen-like belief in the rightness of fate that to some extent parallels the notion of karma. So that, for example, when I said to him at our first meeting, "So far your career has been a mosaic of different musical styles," he could laugh, "Well, at least it's artistic," but he could also stand back and respond in depth.

Like this: "It 's hard to remember what my consciousness was like when I was 19, 20, 21, y'know? Back then, I didn't feel like I was really at my potential, but that I was discovering my potential. So every event that took place in my life back then, and even before then, and even now, is all perfect. I believe that to be true for everybody. A lot of times people who might have wanted to be musicians might sit when they're 30 or 35 and look back and try to think what it might have been like.

“But I believe that every single thing that has happened to me has been perfect in its own right, that every single thing has led to something even if it looked at the time like I was declining or losing status or whatever, it was still perfect. You know, fate seems to know no success in the material form -- I don't know if that makes any sense. But what I mean by that is that I believe your personal development is a reflection of all the situations in your life. And if success in the realm of the arts is the important thing for you to experience, then it will be.

"But I don't look at anybody who isn't famous as being less than anybody who is; as a matter of fact, I don't hang around with famous people because, well, either because I'm shy or because some people take their fame in a way that I don't want to be exposed to.

“Don't get me wrong -- I bask in my good fortune. But if I weren't famous, I'd still be basking in the things that I enjoy. And anyway, when you look at it I'm not really famous; I may be in the music business, but when you think about what fame and history really mean, that's something different. I believe that there are musicians right now who are 'famous' who won't survive history, but I also believe there are people alive right now who will be historical figures, whether they're famous now or not."

That longer view of how musical history works gives Vai perspective; no past experience, no present or future potential looms so large that it obscures the arc of the whole -- kinda like his solos, come to think of it.

As he says, "But getting back to how this relates to my looking at how I was with Frank Zappa [laughs], all I can say is that with Frank I was learning so many things that I look at that as my early days. Same with Alcatrazz: it was early days, and I was learning. And now with Dave ... Well, probably when I'm 40 I'll be looking at everything as my early days, y'know [laughs]? But I've found that whatever happens in my life, even if it goes wrong, it's still perfect."

Perfect perhaps, but definitely variable. Basically, there are two broad marketing categories that Vai's work up to now falls into. First, and most lucrative, is the stuff like Alcatrazz and Crossroads and David Lee Roth, which attracts at least a fair amount of public attention. Second is the more experimental, walking-the-edge feel that threads through his solo stuff and his more outside work with Public Image Ltd and L. Shankar. Reconciling those two different aspects of his musical personality has led Vai to do some thinking.

"I have to approach that question on two levels," he begins. "First, on a career-minded level. On that level, when you want to build your career into a megastardom-status-type thing, a lot of it has to do with the packaging. That is what David Lee Roth is one of the kings of, packaging.

“And there are certain things you do and certain things you don't do for that type of a mega-type view. If I wanted to approach my musicality in a very big, career-oriented way to make a big impression fame-wise, status-wise, then I'd do certain things: I'd play certain music, I'd release certain things at a certain time, and I wouldn't do other things. For instance, I get a lot of offers to play on other records and stuff that I don't do because we're building a band image here, and I don't want to be looked at as a studio musician.

"Now, there'll come a time when I will do those things, y'know. I've only realized this recently. In the past I just played the music that I wanted to; I liked projects, I looked at things as projects, and tried to concentrate my mind on each project. When I did something like my solo record [Flex-able], that was a project to me, and that's what I concentrated on; there was a whole aura and a vibe about that whole thing, a certain way I approached everything I did to be a reflection in that music of that time.

“But back when I was doing all that stuff, I never understood what it meant to take certain steps in order to make a big impression. But now with Dave, it's another approach. I'm taking the approach that it's an opportunity to play music that I very much like, and with the new partnership that Dave and I have for music production, I get to express myself a lot more. So you'll hear on the record that there's a little bit of those other schools of Steve Vai thought in there, in this music, even though it's still very much David Lee Roth. And fortunately I still keep in mind the enjoyment of the music, the fact that I love playing the music."

It would be very difficult to come out from a show after seeing Vai careen around onstage with the energetic abandon that he does and not believe that. But at the same time, there's no radical discontinuity between the flowing-haired lunatic burning up his strings and doing splits and the reflective guy with the solder-covered dungarees a couple of feet away. He's two Vais in one, and the intensity burns through them both equally; it 's just given different outlets, means of expression.

Which is largely how Vai himself sees the relationship between himself onstage, in the studio and on the street.

"Well, like we were talking about before, because of my past experiences, my attitude changes. A lot of people feel that they're different people when they're onstage, in the studio or even on the street; they become these different people. I don't, I'm the same guy. Maybe certain aspects of my personality become exaggerated when I get onstage, or certain kinds of technical expertise that I might have learned and then hidden away might become more apparent when I'm in the studio, but I'm always the same guy. And so's everybody else.

“You're fooling yourself if you think you're a different person because you're in one place or another, because you're not; you're only acting on the stage, or else you're only acting in your daily life to cover up what you really are until you get on the stage. For me in the past, the stage has sometimes been a kind of creepy experience, because I'm actually kinda shy about what I do while playing, but once I start playing it's a great communication."

Communication takes a sender and a receiver, though; and when he hooked up with David Lee Roth, Vai couldn't be sure that the folks in the audience might not be out there to jam his messages rather than pick them up. He found out differently, to his relief.

As he puts it, "To be honest with you, at the beginning of the last tour, I didn't know -- because I didn't listen to what people were saying, I didn't read any press, I didn't want to be influenced as to how people were thinking about what I was doing with Dave, because of the inevitable Van Halen comparisons, which was weird, because I love the way Edward plays -- so anyway, I didn't know what was gonna happen when I got onstage. I didn't know if when I got up there people would throw things at me, y'know?

“I had dreams about eggs coming down [laughs]. But at the same time I felt confident; I realize that no matter what happens, no matter what people think, I have to get up there. So even if there's only one guy in the audience who is enjoying what I'm doing, then I'm gonna play for him, and God bless him.

“So I was very happy to find out that, when I stepped on stage with Dave for the first time, it was amazing -- I couldn't believe the response. It was a relief, to say the least; and by the time the tour was halfway over people were chanting my name. So anybody who was there and did that, I'd like to thank, to say the least [laughs]. And by the end of the tour I didn't feel like I was filling in for anybody or taking anybody's place, and neither did the audience. So I started grooving on the whole thing severely [laughs]."

Characteristically, Vai uses that experience to make a larger point: “And as we're sitting here talking, after me spending the last few months in the studio working, I've been thinking about the road and the tour and getting so excited I sometimes feel like I'm gonna explode [laughs].

“Really. I just love everything about touring; it can get hard, but it only gets as hard as your attitude toward it. Some people hate what they do and find real horror in everything; but even if it is a horror, if you just tell yourself, 'This is great and I don't care,' you can make yourself take a more positive approach. To me the road is the ultimate vacation anyway, a great experience."

Combining that kind of enthusiastic intensity with his studied chops, the only shifts Vai has to make when he goes from stage to studio are shifts of emphasis, not of mindset.

"Now, when I get in the studio, it's the same guy but with his different aspects out front. There are different ways of approaching the music for the studio, because now I'm getting it on tape, and so I'm doing it in more of a technical fashion. I mean, all the same 'spirituality' is still there, the spirit you put into it, but you're not gonna run around and jump around in the studio. It's a more compressed type of concentration. I can tell you I aged a lot more doing this record than I did during the last tour [laughs]. We put a lot of hours in of just plain hard work.

"Fortunately for me and Dave, we do see eye to eye, we do have a lot in common, and that's why we're still in good standing with each other. Because if the kick drum is too loud or too soft, it's all a matter of taste. Music is art, and there's nobody to really say, 'This is the way it should be or shouldn't be.'

“Of course, you're not gonna go and print your kick drum at + 20dB, either [laughs]. And if I were sitting alone, doing all these things alone, it would just be my own personal taste involved. But with this album it was with Dave, and so we discussed things and came to decisions; that's the way everything went. It's just an informal relationship, y'know.

“Dave is the executive producer: he's the one who makes all the decisions about what songs are gonna go on the record and things like that, although we talk about everything. And he's very much involved in everything.

“I'll play him a bunch of different EQ's, for instance, and we talk about whether it needs more or less high end or whatever. Almost every step of the way we took together."

The album went well, if you judge it by the sonic results; but there was a key casualty along the way. Bassist Billy Sheehan, the fiery two-handed tapper who translated that six-stringer's attack to his own ax with such finesse, left the band once the tracks were completed.

Stories of behind-the-scenes flare-ups are exaggerated or untrue, according to Vai: "I mean, I wish I could sit here and give you the kind of big gory story that everybody loves to read and start some nice soapy media gossip, because then everybody would want to interview me [laughs]. But I'll leave that to somebody else [laughs], so let me put it to you like this.

"When two people get together and they're playing music and everything goes fine until one of them wants to do something different, it's best to get together and talk about it, and if one of them decides to move on, that’s it. It was Dave's decision, but it's best for Bill and it's best for Dave; that's at least the way I feel about it. And there don't seem to be any hard feelings going around; it's not like the Van Halen extravaganza [laughs]."

More to the point in any case, as Vai sees it, is how the band recovered and came back from the blow that Sheehan's departure inevitably dealt them. "The main thing is the band sounds really good now, even if it's a different good from before. You know, Matt is [drummer] Greg [Bissonette]'s brother, and they've played together for their whole lives. So they've really got this chemistry.

“Even the way they argue is their own language, every way they communicate is their own language. If you slap one guy in the face the other guy feels it [laughs]. They're like Siamese twins. They kid around about it, too: one guy'll drink a beer and the other will spit it out. But the main thing is that they really work together well Greg is a great musician; we only found him after auditioning literally hundreds of people. And then we went out and played 112 shows over six months -- a nice leisurely pace, right [laughs]? But Greg never dropped one beat on that whole tour. Never. He's amazing.

"Now of course, Bill is a very fine, very very talented musician. So I thought, 'Okay, there's no way we're gonna settle for anything less than something that's gonna work great here.' Greg was very reluctant to mention his brother because he didn't want it to be too awkward for everybody; but then when we heard and saw him play, I was really surprised that he was such a fine player.

"He's not a flash enthusiast, but he's very very solid, and since the two of them are together all the time, it gives the band a real pump. There's something about the genetic structure of the rhythm section that makes me very happy to be playing with them. It's like what Hendrix must have felt with Billy Cox and Mitch Mitchell as a rhythm section, it's just welded together. These guys are like the Cement Brothers [laughs]."

At this point, out came the tape, the precious tape, as they'd say in Road Warrior; the one that, by his management's righteous decree, couldn't be heard unless Steve himself was there playing it. And so it traveled with him cross-country when he came back to his parents' Long Island home for the Italian Christmas fiesta, making only one significant sidetrip: to Guitar World's offices on 25th Street and Broadway.

Set up across a row of filing cabinets are our listening tools, a Sony portable cassette deck and a pair of self-powered AR speakers. When we first pop the tape in and hit the play button, a bunch of crackle and a bit of flutter distract us, and so Vai, ever the tinkerer, leaps up and begins re-checking all connections in his best techie mode, finds the loose ones, replaces the batteries ("The speed is just a bit off, too slow," he explains) and suddenly flooding the office are the sounds of the months-off release by David Lee Roth and his powerhouse band.

Not being a raging fan of Eat 'Em And Smile, I'm really not sure what to expect, but whatever I expected, Skyscraper sure isn't it. Oh yeah, there are a couple of songs that fit the David Lee Roth mold as previously defined; but even within their apparently predictable turns lurk classic Vai spins on the metalhead moves that too often seem flown in on remote.

Vai, it seems, is never on remote; he's always digging in here a little harder, slurring a note for two bars where somebody else would try to make it from one end of the fretboard to the other in that same time for no other reason than to show it can be done (like we don't all already know that), biting off a quick flurry of a riff here, stabbing some whammy lunacy deep into the tune's entrails there, looking for the unexpected with a rocker's vengeance. Time after time, he finds it. Let's follow him, then, as we put our feet up on Noe's desk and Vai takes us through the album's surprisingly varied cuts, one at a time.

Track one is a kickass rocker called "Knucklebones."

"That, or the majority of it, anyway; was written by Greg and Matt Bissonette," Vai begins, "then they brought it into rehearsals, where we all kinda mushed it up [laughs]. It's a pretty simple rock song. All the guitars were [recorded at my studio]."

There's a stunning mid-section where all the other music drops out and Vai is left doing Delta-style blues part on electric. “A little Ry Cooder influence there," he grins happily.

"I never really played that type stuff before, and now seemed as good a time as any to do it. It's a real pie in the face -- whaddya, expecting something normal? Basically it was styled around the demo, which was the product of our rehearsing the song and coming up with a formula for it.

"This song was laid down like all the other ones were, more or less: Drums were put down first, the bass was overdubbed next. On this one, vocals went down then, and then I did the guitars. I was using just my basic amp set-up, which is my Marshall thing."

Next up: "Just Like Paradise."

"This is the first single," says Vai, "so it's the one where I'm using the triple-neck. It was written by the keyboard player, then mushed together in rehearsals. It didn't take that long to mush [laughs], because a lot of it was in the computer. All the keyboard parts were sequenced, and so the song didn't really take anything much to put together.

“He had all the keyboard parts together, and brought it over so I could put the guitar parts on the demo – demo number one - which is the quick demo. I did a certain solo, it was like one pass; I wanted to throw a little something on there, so I threw the echo on. Then we did the real demo, which is higher quality, and I did a completely different solo. Well, Dave ended up liking the solo from the original demo, so when we made the record I learned that solo and put it there.”

The solo, in fact, appeals at least partly because of the Hendrixy feel to it, is due as much to the way the delay and echo feed off the tone as it is to Vai’s swooping attack.

"I had an idea for this song that would have been even more along those lines," explains Vai. "What I wanted to do was a double solo: I wanted to play two guitars and pan them left and right, have them solo against each other, do answer licks, harmony licks; but I never got to that because that original solo became everybody's favorite. It’s got that California key change in it [laughs]. But lest you doubt it, the solo is pure Vai, complete with upper-end harmonic squeals throughout. "You don't usually hear those on a commercial song," he comments. "But that's me, always trying to get my two cents in [laughs]."

Following the album's third tune, an intelligent basher called "The Bottom Line" is the adventurous "Skyscraper."

"That one's a little different for Dave," Vai says candidly. "It's a song I had written backstage one day and didn't think it would be anything he’d like. But when I played it for him he loved it. Visually, the things that he's speaking in the verses turn into audible sounds because of the ways we're using the effects.

“See, we opened up a book to this guy climbing a mountain, hanging on in the middle of the vast openness – a very breathtaking photo -- and Dave said, I want it to sound like that [laughs]. It shows that there's a lot of different sides to him other than just being a rock star, that he can do something like this and be comfortable with it. "

Vai's efforts here to match guitar sound and feel to the song's intent take the form of constant pitch-wobbling via controlled wang-bar diddling, which strongly suggests somebody hanging on to sanity’s sheerer sides with only their fingernails. "That's me," he nods smiling, "standing on the last branch of a small tree. It's one way to the top."

Once again, the demo solo proved more durable than Vai would have imagined. "The solo is the same as the demo’s, but I replayed it. The one I played on the demo might interest you for a couple of reasons. A friend of mine built a pyramid for me to meditate under; it was a gift from a long time ago. It was in the room next to my studio, so I went in there and did the solo for the demo; it inspired me. I couldn't fly the demo solo in because the speed of the song was a little different.”

Many other aspects to this track elicit commentary. The acoustic breakdown toward the end, for instance, which in its sonic textures is reminiscent of John McLaughlin's Shakti, required a change of ax, according to Vai: "That's a twelve-string and a very clean electric with tons of processing. It's an ethereal approach, that song; you should listen to it with headphones, it's pretty funny."

There's myriad uses of panning effects: "We had a great time with that one. It was very time consuming, getting all the effects on tape and spatially locating everything. When we did the mix downs, I made sure we used Massenburg automation; I learned a lot doing this project. Whereas in the past I would end up doing everything completely dry to tape as best as possible and then putting all the effects on in the mix, this was completely different. We had two 24-track machines locked up, and if we ended up having to put effects on everything we mixed, we'd be dead [laughs]. So in a song like this, we printed the vocal effects, but I printed them on a separate 24-track machine-so we had 72 tracks.

Actually, the whole album ended up being 72 tracks, except for the next song. And then we did a vocal slave; I just mixed the vocal slave stuff down to Slave One, which you use two machines for. I usually don't print with any reverb. We don't do that because that's real subjective, unless you print it on a separate track, an effects track, where you can bring it up and down. If you've got 72 tracks, you can usually find the room [laughs]. It was fun, a much different approach from just going into the studio and knocking everything out. That's great too; I've done it, and Dave's done it for years and years.

And this stuff still has a very live quality. The album's ballad, next on line, is called "Damn Good," and evokes, with its building clusters of guitars, some of the lengthy Led Zeppelin classics that aren't far behind music of this type.

"Well, you know how that goes," grins Vai. "I wrote that song when I was 14; of course, pave wrote all the lyrics. The way that one came about was at the last minute. We'd talked about putting an acoustic guitar solo on the record-just guitar for like a minute and a half, a virtuoso type of thing. I was gonna start it with that lick, just with those two chords that open this. Well, I played those two changes for Dave and he liked it, and I said, 'You know, I wrote a whole song around this,' and I played it for him. And he goes, 'Here, play it again and I'll Sing you the lyrics [laughs).'

“So that's how we decided we wanted to put it on the record. The way it was recorded, as far as the guitar sound you're hearing, was with about 12 guitars: a doubled acoustic six-string Guild, a Guild twelve-string, two Guild twelve-strings at half-speed so it's actually double-speed, a Coral sitar, a clean electric guitar and a six-string at half-speed. They all come in on different parts of the chord.

"The solo is another one where I decided I just wanted to play a melody and not the standard thing to do on a song like this: crank it up and do a rip-roaring melody solo with a fast lick in it. Well, I wanted to experiment with it, so what I did was play that melody, which is being played on a double-speed twelve-string, a Coral sitar and a backwards electric guitar. The way that melody was recorded was fun. I played it, wrote it down in manuscript form, and then I wrote it backwards in manuscript form, learned it, flipped the tape, and played it to the music. That's a little tricky -- very very tricky, in fact [laughs].

"So when you flip it back you have this backwards melody. But it's funny, because you have to think totally backwards. While you're recording that way you don't play on the beat; you play right before the beat, so that when the note hits it's on the beat, more or less. 'Cause what you hear when you're re-cording backwards is after the beat; attack and decay are reversed. And besides, playing on something backwards is one thing, but actually trying to arrange something... [shakes his head]. But that reversal, when you Hip the tape back over to regular playback, also gives you a kind of ghost melody that does some funny things ...

"Hot Dog And A Shake" is a raunchy kind of vaudeville rocker out of the David Lee Roth mold. But Vai's guitar work studiously avoids any kind of mold, deliberately dancing around the expected, thus creating a musical tension that expands the tune 's possibilities. "Every time I expected you to do something that's exactly what you didn't do," I say, and Steve asks, "What are some of the things you expected to hear'"

"I expected more the superspeed fills, and whenever I did, what happened was you'd take one note and make it into a grease stain," I say, and he laughs, "Yeah, the noodle effect. It's funny, but those licks are shaped like my body [laughs], you know, lanky. You are what you play, I guess.

He pauses a minute, then picks it up: "It's obvious these days that everybody can play pretty fast, and there are people who are playing so fast that it's inconceivable. I don't play fast or not play fast because of what somebody else is doing; you can't compete that way. I feel that if you do try to compete with how somebody is playing fast, you're defeating the purpose of expressing what you want in your music. I guess some people need to express playing fast all the time [laughs], but I'm trying to stay away from that; I don't want to be known as a speed freak or something like that.

“It's funny, actually, the way this whole solo section came about. When I was doing the demo, I really didn't have anything planned, outside of a few ideas. I mean, you can sit and punch things in all day long, but I wanted to see what would happen if I just hit a long note and didn't do anything else about it, just waited to see what it did. And it 's funny, because on the particular evening I cut this, I wanted to lay down most of the solos on the demo, because they were just demos and I wanted to get them done for us to have.

"I remember the night I did this song because there was an Alice Cooper concert in town and I really wanted to go to it but I couldn't because I wanted to finish this stuff. At one point when I was doing this solo I hit the long note and just let it go, let it arc and feed back and go a little out of tune, then went into a fast lick; and right in the middle I just decided -- all this went through my mind in a split second -– to stop playing, just finish the solo because I didn't like the way it was coming out.

“See, my idea was to just play through and see what happened. So I thought to myself, 'Stop, go to the concert or something and come back and finish it later.'

Then right after I stopped in the middle of the solo I started feeling some anxiety because I wanted to go and I also wanted to finish the solo. So that aggression came out in the rest of the solo."

It does indeed, as Vai pours molten cascades of raunch across the small speakers in the GW offices, which then resolve into a moving riff, anchored in its rhythmic pattern as it travels up the fretboard via split-echo twin guitars.

"This is called 'Stand Up,'" Vai says before he hits the tape machine again. Three minutes or so later he explains," That one was written by the keyboard player and severely mushed in rehearsal. That fill at the end of the first verse that just kinda jumps out at you with the stereo echoes from the SPX90 is from the demo -- all the fills and the solo on this are.

“So it's all just like BOOF! not much thought, just done. But there are a lot of cute little noises in this one, like the panned chirping noises. And I really love the solo, the way it kicks off with that sustained low note that never bottoms out, keeps sneaking by. I like playing long notes like that better than quick ones, first of all because they're easier [laughs], and live you can hear them better. I rarely play fast live because of that. Long notes scream and reverberate in the hall, and you can hear them scream and kicking back at you. I go up into la-la land when that happens, really. "The harmonized ride-out with two guitars winds things up with a flourish.

"This one is ‘Tahina’; it's about the Tahitian goddess," says Vai. "This is all one guitar with a 360 ms delay between the left and right sides, so I'm playing against myself with the song. If you listen carefully you'll hear that everything I'm playing on the left side is then repeated on the right side.

"Having said that, he positions me directly in the middle of the two speakers, for the max effect. It works. "Some of those parts are pretty intricate to be bouncing back and forth when the chords are changing behind them," I open, and he nods. "You've gotta make sure you find notes that work in both chords that it's gonna happen over. When I first wrote that piece, there was one chord change in particular that I thought was really odd because of the echoing. But I just ended up saying, 'The hell with it [laughs]; who cares? 'As long as it works ... "

"What about the way those fills arc up?" is my next gambit, and he explains, "What it is is, when you've got a certain amount of millisecond delay, like a quarter note, say, and you want to build a chord, and you want it to have a certain sound, like a triad, you have to move up in some regular way. So on this, I moved up in half-step form in eighth notes, so that I'm gonna have thirds when it echoes. That solo is also from the demo; I doubled it, so I had half-note echoes-720 ms. And it's got a Harmonizer on it in fifths, a fifth up, and it's panning, so it's very Hendrixy."

"That brings up something," I venture. " It doesn't seem like, in this solo or a lot of the other ones, that they're about notes per se; it 's about sounds."

" In this song that 's particularly true," he agrees. "Listen to it with headphones and you get a little chill at the base of your neck when the things pan. Everything's moving all the time on this one."

Next up is what Vai describes as ' ''a more commercial song called 'Perfect Tinting’."It 's an accurate enough description, up to the tune's end when Vai seems intent on ripping the wang bar off his guitar 's body. "Might as well overuse it while you 're into it," he deadpans. The solo demonstrates one of the reasons his acute sense of structure -- Vai stands apart from the metalhead pack.

Opening with a succinct phrase, Vai picks that phrase up and first repeats it, modulating It over the changes via different positions, while locking into the basic rhythmic pattern shaping it, then expands it, twists it around a bit and finally opens it up for the vocal-led breakdown - a kind of metal dub section. "I can think of the perfect cartoon to set to that part," I suggest. "Remember those old Looney Tunes where one corner of the screen will open up and somebody's head pops out of it, and all of a sudden it expands to take up the whole frame?"

"Last song," he announces as he gets up to turn on the tape machine again. "It's called 'Two Fools A Minute.' This one has Dave being a little more Dave - the top hat and fun guy Dave. I wrote the brass arrangement." The fun is apparent in the music: everybody's phrasing sounds like a Salvation Army band after a bender. "That's Dave; we just expanded what he does in that mode to cover the entire band," grins Vai. "Bill did a nice ripping solo; it was a little different for him, because it was very clean, but he really just rips it up. And the tune is funny without being stupid. "

That, as they say, is that. But one question remains, with a spring tour looming even over these winter holidays. How are the boys in the band gonna boil all this down into stageable form?

"The short answer is, 'We're not,’” grins Steve. "The record's too hard to do, so we're calling off the tour. But seriously, folks," he continues, "it's actually not gonna be that hard at all; so far in rehearsal it's sounding great. I like playing the solos that are on the record for the most part; some of them might not be note-for-note, and undoubtedly each night will be a little different. But I made sure while we were cutting it that I had a way out to do everything live, so that we can do the stuff and sound cohesive. The new Harmonizer will help with that. Anyway, when you're live, at least in this band, there's a whole other atmosphere.

“There's a lot of vocal effects we'll cop, but the way David Lee Roth communicates with an audience live is more a personal thing than an audio thing. Not to say that our audibility will be impaired, but I guess what I'm saying is, when you go to our concert I think it'll be very exciting to watch the band and get off on our energy, the volume, the colors, the clothing, the staging -- that’s all part of the atmosphere. 'Skyscraper,' for example, will sound great; in fact, to me it sounds much better because there'll be heavy guitar on it for the show. I'm gonna go all out with that one. Another point is that I don't like to have rhythm guitars underneath me when I solo, and so there aren't many times that happens on the record either. And the main thing is that the band is really good."

"What about the more coloristic and atmospheric solos' How will they translate to the stage'" I ask.

"I don't see that as a problem," is how Vai comes back. "I prefer doing that kind of thing live to doing it in the studio. I do it differently, it's another whole state of mind. The notes might be the same, it'll be a little sloppier, but it is live, and live there are a lot of other things that I get off into, things other than just playing the notes. That's part of the show, part of what I like to express.

“My favorite thing is to hit one note and know that before I hit it I'm gonna hit it. That sounds simple, but it's true; to me that's where all the joy of playing comes in. You know what you 're gonna play, you go for it, and it's there. For me, my whole persona becomes part of that thing that I'm going for.

"Mentally, you get moody sometimes, sometimes it's not quite there. It might not sound like it's there to you, but it might be there-and vice versa. I mean, when I was doing the solos for this album it was like, BOOM, this is good enough for the demo, but then everybody loved it and so we go with it and I end up liking it a lot. So they turned out to be good enough for the demo, the album, and the tour: good enough to live with."

A bit how David Lee Roth must feel about Steve Vai himself.