“I remember my first lesson with Joe. I had a guitar and a set of strings. I’d never really played. I didn’t know how to tune or string it”: Steve Vai and Joe Satriani discuss the evolution of guitar playing, and what they taught each other

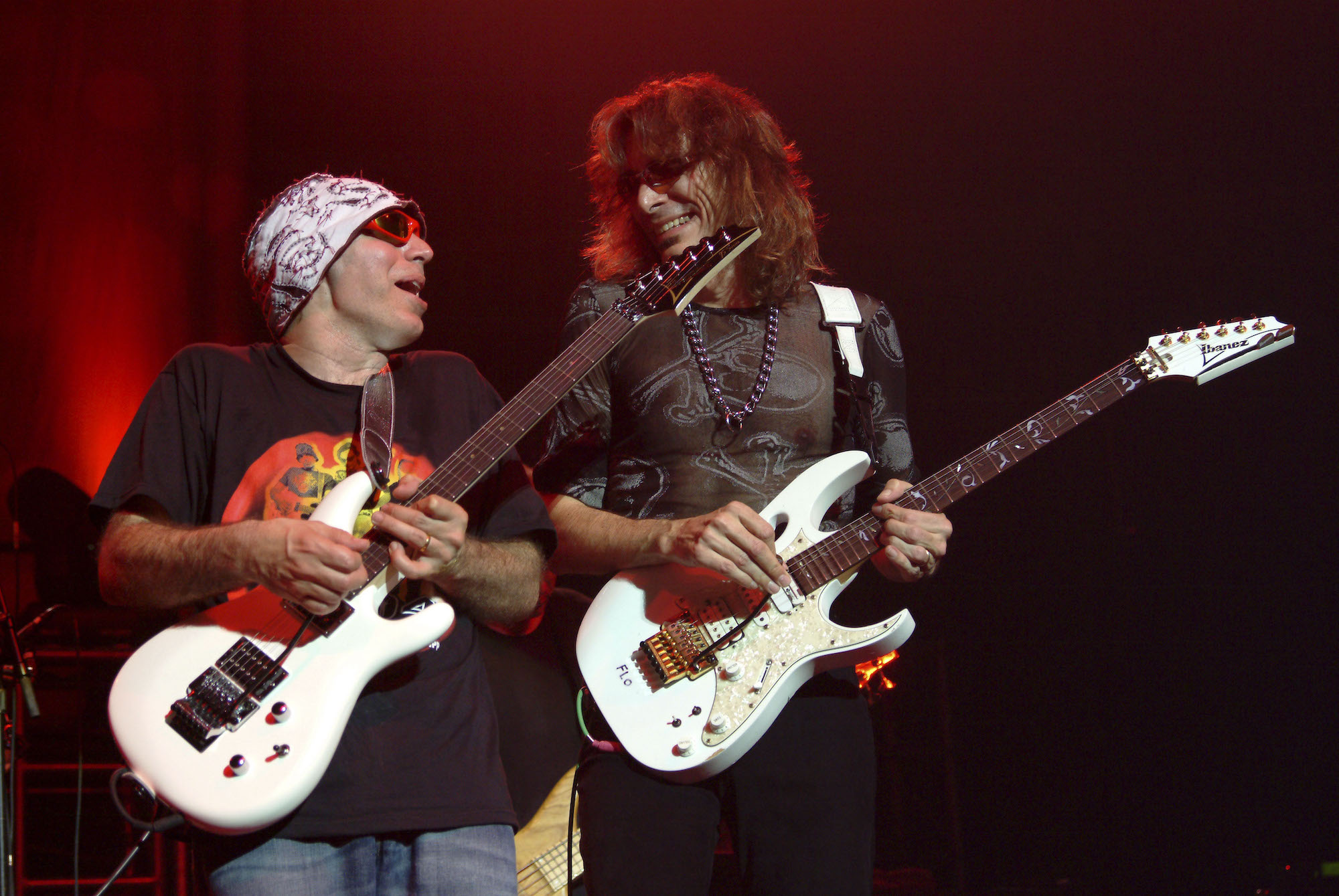

In 1990, Steve Vai and Joe Satriani sat down for an extensive discussion with Guitar World, during which they joked that – when they were older – they would record a song called The Sea of Emotion. Now, more than three decades later, that premonition has come true

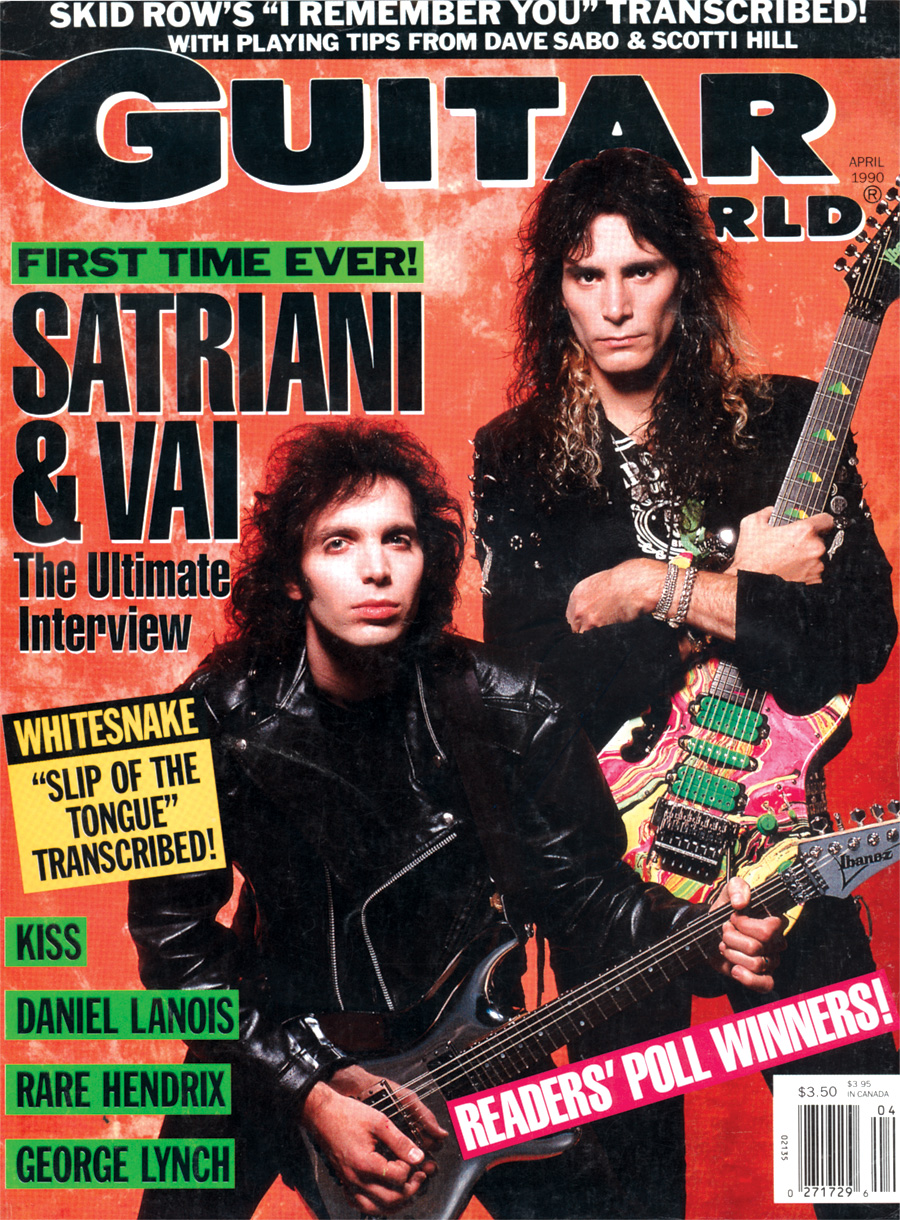

This interview with Joe Satriani and Steve Vai originally appeared in the April 1990 issue of Guitar World.

Before Steve Vai and Joe Satriani burst onto the scene, Carle Place, Long Island, qualified as the land that time – and everyone else – forgot. But as the boyhood home of the two monsters of “intelligent chops,” the suburban town stands at the center of the earth for countless guitarists.

It is no coincidence that the two hail from the same sleepy suburb. Satriani was Vai's first guitar teacher and, as he confirms in the interview below, his musical as well as personal mentor during their teen years.

Satch and Steve remain close friends, and continue to hang out together whenever their schedules allow it. Today's meeting is in the presence of an interested third party – Guitar World.

It is an ideal moment for a steel-string summit – Joe's Flying In A Blue Dream and Steve's debut with Whitesnake, Slip Of The Tongue, have just been released.

The scene of the get-together is the control room of Steve Vai's home studio in the Hollywood Hills. The room is comfortable, domestic – a creative disarray of recording gear. Vai's collection of axes stands in one corner, the various headstocks neatly ranked like a column of soldiers.

As we wait for Joe to arrive, Steve plays for me a rough track from his forthcoming solo album, which he follows with the Slip Of The Tongue master. His guitar tears through the tracks with fiery grace, opening up new perspectives on what we usually think of as Whitesnake.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When the Whitesnake offer first came along, I was a little apprehensive,” Vai admits. “But as soon as I heard the music, I was hooked. It was an open canvas – just bass and drums. And they said ‘do what you want.’ I couldn't refuse. It was so exciting to hear this type of rock music. In my mind, I was decorating it already. I was hearing all the little squeaks and squeals and the big rhythms and solos instantly.”

From Whitesnake, our talk turns to Carle Place: delicatessens and diners, the village psychopath, local kids at school...

“There was this family in town called the Calavagnes. They had seven or eight kids. One of the older ones was in a band with Joe. They used to do all the Led Zeppelin songs and stuff. The name of the band was Tarsus. And when I formed a band with the younger brother, Barry, we were like a carbon copy of those guys, only four years later. We even named our band Susrat, which is Tarsus spelled backwards. Later, we changed it to Rage.

“Joe taught us all the songs that Tarsus used to do. We used to play all the clubs and it was really cool. The Calavagnes' house has so many memories for me, too. That was the place where... you know when you're growing up and you first experiment with drugs and sex and everything? That's where it all happened. In the Calavagnes' basement, which was just a crawl space under this big house in the middle of town. The school and local pizza joint were right in back. And then there was the Sea of Emotions, which Joe will tell you about.”

As if on cue, Joe Satriani steps through the door, guitar case in hand.

Standing side-by-side, Satch and Vai are a study in contrasts. Dressed in black from head to toe, Satriani is a compact, quiet man who radiates a sense of inner intensity – like the eye of a hurricane. Vai is more outgoing, wheeling energetically around the cluttered control room, standing a head taller than his former teacher, his long limbs draped in the most wildly multicolored running suit you'd ever care to observe. He does much of the talking, but always leaves Satch space to get his licks in.

Vai: “I was telling about the mirror image band situation with Tarsus and Susrat. How we'd emulate your band. In fact, someone told me that before each gig you guys used to go have Coca-Cola and eggs in the morning. So we started doing that.”

Satriani: “Great. Which is probably why he's sick right now. It was the old clogged artery diet.”

So you two never actually worked together in a band?

Satriani: “Oh no. At that age, when you're in high school, ninth grade and eleventh grade are a long way apart.”

But you did have lessons together.

Vai: “Yeah. It started out where Joe was teaching a friend of mine who lived a couple of houses away. My friend was actually able to hit notes on the guitar, and I thought that was phenomenal. And he said, ‘Well, you should see my teacher; he can really play.’ I couldn't really afford lessons, so I chipped in with another friend and Joe taught us both at the same time.”

How long did that go on for?

Vai: “Maybe a year.”

Satriani: “I'd say that would be pushing it. I can't recall exactly when it happened, but I do seem to remember suggesting that the lessons be separated – that more could be accomplished if we did.”

Vai: “Yeah, you could get an extra five bucks! [general laughter] I remember my first lesson with Joe. I had a guitar and a pack of strings. I'd never really played the instrument. I didn't know how to tune or string it or anything.”

Satriani: “But you played accordion, right?”

Vai: “Right.”

Satriani: “I immediately said, have some Coke, have some eggs....”

Vai: “Sit for a while in the Sea of Emotion, drop some acid....”

Satriani: “Do that for a few months and then we'll start to get to notes and the strings.”

All right, all right, what is the Sea of Emotion already?

Satriani: “The Sea of Emotion? It's a place.... [To Steve] You know, I went back there when I was in New York a few months ago. It looked so different.”

Vai: “I remember the sewer ramps used to seem so large. And I went back and they were around this big.”

Are we talking about some kind of dump here?

Satriani: “No, it was a field, part of an old farm where they'd built three schools. The field sort of dipped down, almost as if it was a dry lake bed. It was a place where you'd go to think – to pour out what was in your mind and in your heart. [to Steve] I must have brought you there one day.”

Vai: “Yeah, in your Volkswagen. We were driving around and we just sat there a while. At the time, I was so in awe of Joe because he was the teacher. I used to just sit and listen. He'd pour out his heart and.... [laughs] No, it was just that back then, like you were saying, because we were several years apart, there was always this great admiration factor from us younger guys for the older guys.

“When I was playing the (Nassau) Coliseum recently, I got on my bicycle and rode all the way from the Coliseum to the school. I always take a bicycle on tour with me. And I actually went to my first kindergarten classroom, which was still there. And I saw some of the teachers I had known in high school. [To Joe] I saw Mr. Nichol and we talked about you for a while.”

Satriani: “Really? Mr. Nichol. He was at Woodstock. He was in the movie.”

Vai: “That was his big thing: ‘You gotta be prepared. I was at Woodstock and nobody had any food or clothing or anything....’”

Was he the local hippie teacher?

Vai: “He was the mod squad.”

Satriani: “It must have been hard for those young teachers, when you think about it. Because it was a pretty conservative school. And the kids... we were pretty snotty.”

Vai: “Bill Wescott was a big influence on both of us because he was our music teacher at school. Joe learned a lot of theory from Mr. Wescott; but unlike most musicians, he applied it on his guitar. Most musicians, if they learn theory, they'll just apply it in a compositional sense.”

Satriani: “Most of the other people in the class were in the orchestra. So their outlet was sheet music. Whereas I took it right into rehearsal and tried to figure out how I was going to play Since I've Been Loving You with this new information I'd gotten about scales or something.”

As soon as I learned three chords, I wrote a song with three chords in it

Joe Satriani

Vai: “And that's where we were different. I started taking theory classes, but I was approaching them the same way as the orchestra kids. I started taking lessons with Joe and realized he took what Wescott had shown him and put it right into the guitar. And he was kind of feeding it back to me. Making available all this theory. And that's where Wescott was helpful.

“He was a very demanding kind of teacher. He had two theory classes, Theory I and Theory II. And when I was taking Theory II he made me write a song every day in manuscript form.”

I was going to ask if either of you were writing tunes back then.

Satriani: “Oh yeah. As soon as I learned three chords, I wrote a song with three chords in it. But when the lessons really kicked in with Wescott, one of the things he taught me to do was write away from any instrument. That was a heavy concept at the time. And also to take out some manuscript paper and write without really knowing what I was doing and put off reading it till the following day. Just to get into the frame of mind that you could write music that had nothing to do with your physical abilities on whatever instrument you were struggling with at the moment.

“He said to me, ‘It might turn out that you're not a very good guitar player. You might not be as great as Hendrix or whoever. But it doesn't mean you can't write good music and be a musician.’ Of course I probably said something totally rude to him. But I probably went walking down the hall thinking he was right, and that has helped me out quite a bit. Because I have come up against a lot of physical barriers that are stuck in Joe’s body. So thank God for those lessons where it was really pure music. It was intellect and heart bypassing the tendons and muscles.”

Speaking of influences, do you two have a lot of guitar heroes in common?

Satriani: “I don't know. Let's find out.”

Vai: “I'm sure we were all into Hendrix.”

Satriani: “I was a big Jimmy Page fan.”

I remember when I first started hearing Roy Buchanan, I saw a picture of him and I thought, ‘Why would anybody want to play a Telecaster?’

Steve Vai

What about guitarists who were a little more off the beaten path? Roy Buchanan, for instance?

Satriani: “Yeah. He was brought to my attention when I was about midway through the real impressionable age. The rhythm of his music was completely different from the way that I felt rhythm in music. I never got into his records and his compositions as I did with Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, and Black Sabbath, because that felt more natural to me. But I was so incredibly impressed and bewildered as to how he went about it.

“I think it was years – until I finally saw him on television – before I could figure out how he was getting that kind of sound. Back then, I think I was really impressed with personality. How could someone come along and sound so totally different? Meanwhile, I always had this same little noise coming out of my amp.”

Vai: “I remember when I first started hearing Roy Buchanan, I saw a picture of him and I thought, ‘Why would anybody want to play a Telecaster?’ Because here I was listening to all these bands with these huge guitar sounds. And I always thought the Telecaster was a very naked instrument.”

Satriani: “How did Page get away with it, you know? I often think about that.”

Vai: “You think he did get away with it?”

Satriani: “Well, I mean he used it on the first two (Led Zeppelin) records. There's a lot of Telecaster on there.”

Vai: “I was always under the impression that it was all Les Paul.”

Satriani: “But it wasn't. It was a Danelectro and the Telecaster. I saw a video of Led Zeppelin, real, real early, doing Whole Lotta Love. He looks rather... like this, you know? [Snaps fingers, beatnik style]. He's got, like, a wah pedal and maybe he's got an Echoplex. There's no sound effects. They're just standing there playing in front of about 20 people.”

Vai: “With Buchanan, though, you could really understand what a Telecaster was. Eventually, I really got into him. I remember realizing that what he was doing was so naked and pure, as opposed to what I or people I was listening to were doing, which was all about cranking up the amps with tons of distortion and using tons of effects. And I realized, ‘Oh, that's why he's playing the Telecaster.’ I remember he did If 6 was 9. Did you ever hear that version?”

Satriani: “No.”

Vai: “He does this one lick I must have played a thousand times to my friends. He's doing this solo. He's got this real squeaky Telecaster tone and it's almost like he's struggling. And then he does this one riff in the end. He just stretches to the fifth. And he almost gets really sloppy; he's falling apart. And all of a sudden, he just goes like this [imitates a very fast, precise riff]. And I said, ‘God, that's just so hip. He led you to believe that he was losing it.’ That's one of the reasons why he's there.”

Satriani: “He had a lot of drama in his playing.”

What about Al DiMeola? As you can see, I'm trying to mix up the names.

Satriani: “He took me by total surprise. I was never really impressed with guitar players who made their guitars sound less like guitars, and more like pianos or synthesizers, by using precision and muting and doing percussive stuff.

“I don't know why. I love classical music, but I hated classical guitar. But I like flamenco, because there was something else there going on. It wasn't just the notes being thrown at you. And there were certain kinds of jazz that I really liked and other kinds that just went right over my head. But DiMeola was one of the first players – along with McLaughlin and some of the others – that I thought were really bringing a lot of things together.

“It was totally different than Hendrix and Clapton or whatever. But yet you could tell he had some of the same rock 'n' roll sensibility. But I've got to say that it was a struggle to get through it and realize I could never do what he was doing. He was, I think, the first player to come along that made me realize inside myself that I was never going to sound like that person. His display of technique was so intense and he was so sure of himself when he played fast; I realized that was not part of my makeup [laughs].”

Were any of these fusion guys major for you, Steve?

Vai: “Well, actually, DiMeola, since you mention him. When I first heard him, I was totally taken aback. There was a lot that was impressive in his overwhelming chops. But there was something I found missing, and that was the sheer emotion behind bending a string and going into a lick.

“It wasn't until I was playing at the Ritz in New York with Frank Zappa and Al DiMeola got onstage that I really realized his talent as a plug-in performer. Because he came up, pulled out his Les Paul, plugged into Frank's amp. He didn't even touch the settings. Every note just exploded! And his action was this high off the guitar!”

How about the blues players, like, say, Elmore James?

Satriani: “I was into really spooky players – like John Lee Hooker. For a little kid like me, growing up in Carle Place, you put on John Lee Hooker late at night and it's a different reality.

“I try to feel that music from the inside out, because I was really attracted to it. I still have these little reel-to-reel tapes of me trying to play really, really slow. Trying to play notes and have there be silences. Because generally what I was playing after my first three years on guitar just sounds like a bunch of noise. I don't know exactly what it is I'm trying to play and I'm just constantly filling up all the spaces.”

Vai: “Meandering.”

Satriani: “Yeah. And never quite connecting, so you try to make up for it with other stuff.”

Vai: “I still have that problem! [laughs]”

Satriani: “So I used to just try to really get into the sound of it. I liked the fact that there were very few notes. And I love a I, IV, V progression. I always did and I always will. Even if it's just slightly hinted at. John Lee Hooker does the weirdest things with them.

“I was into harp players as well. My brother was really into playing blues harp. So there was a lot of that around. For me, that crossed over into listening to James Brown, Sly Stone, a lot of soul artists that I related to. It seems like there's more going on when I listen to that music. And maybe what the audience really hears is what the music is triggering inside of them, as opposed to what's actually happening on tape.

“The music is more of a catalyst for internal music that each person experiences as they're listening, as opposed to sitting back and taking in all the notes. At least that's how it was to me.

“If you gave me a lyric sheet for one of the songs – ‘I left my baby, I left my baby, I took the train, I left my baby’ – I'd say, well, okay, maybe I didn't relate to that as a 14 year old. But, of course, it was the sound. A record for me was a thing I could put on for hours and hours and not pay attention to anything but the sound. The vibration.”

One day, I was with Zappa and he just said, ‘You're so white’ And he sat me down and played me some really wild, old blues things

Steve Vai

Vai: “To be honest, I was never exposed to that serious type of blues. I never heard John Lee Hooker or any of that stuff. The blues that I was exposed to was the players of the time and the way that they expressed themselves through the blues. And it was always more of a polished approach.

“It wasn't until one day, I was with Zappa and he just said, ‘You're so white,’ and he sat me down and played me some really wild, old blues things. The guitars would just bite. Like Round Midnight and the Johnny “Guitar” Watson stuff. But I was 22, 23 by that time.”

Given all this, how do you feel about all the emphasis younger players place on speed and flash these days?

Vai: “Do you think they do?”

Well, yeah.

Vai: “I think there's less of that than normal. Because of what Joe's doing.”

Satriani: “Actually, he hates my playing.”

Vai: “Yeah, right. I'm sitting here telling you that Hendrix and Page are my biggest influences. I used to think those guys sucked compared to him! I really did.”

Satriani: “I'm still working on him.”

Guys in thrash metal bands were bringing in Stevie Ray Vaughan and Hendrix, old Page, blues... trying to figure out the mystery behind the placement of the notes

Joe Satriani

Vai: “But to get back to the question – before, when some of those more popular, fast guitar players were wailing about, it spawned a whole new school of thought based on fast playing. But when Joe's album [Surfing with the Alien] came along I think that it actually started changing the mentality regarding fast guitar playing. It's saying, yeah, it's important to be able to play fast but it's not the only thing there is. There are other players that might be having the same kind of influence today. Like Stevie Ray Vaughan.

“We were just talking about the blues. I didn't really get into the blues until I heard Stevie Ray Vaughan. I mean the blues blues. Of course there was the Hendrix blues, which was great. But Stevie Ray is the blues, man. As blues as you can get. Head to toe, every album. [To Joe] I remember you were telling me about when you were teaching, a lot of your students were bringing in Stevie Ray Vaughan records.”

Satriani: “Guys in thrash metal bands were bringing in Stevie Ray Vaughan and Hendrix, old Page, blues... trying to figure out the mystery behind the placement of the notes. The restraint behind the sound. So I agree with Steve. I think the day of the fast player is gone. It ended about two years ago. It really isn't around anymore. I can't think of a guitar player I don't like who is out there making records or on MTV – I really can't.”

With Mick Jagger and David Lee Roth, respectively, you've both worked with major rock star lead singer/icons. Have you ever compared notes on these experiences?

Satriani: “The two situations were different. Steve was part of a band that made two very intense records. It was a real rock band – a small unit that went out there and just killed. My experience with Mick Jagger was fantastic, but it was something else. It wasn't a band in the same sense as the David Lee Roth band. It was purposefully a bunch of talented misfits.

“Mick went out of his way to pick all these people that had really nothing to do with each other and put us together in a band to see what sort of mayhem he could create. The shows were very different too. And Steve and I obviously had different roles.

With lead singers of that stature, there's a certain chemical that's there from the crack of the cosmic eggshell. They're a specialized item, those people

Steve Vai

“I was a guitar player in a band that had two keyboard players, sometimes two other guitarists, a bass player, a drummer, four or five singers, and percussion. We did a two-and-a-half hour show where the music spanned from the early Sixties to the present. Whereas the David Lee Roth thing was like, now. Very big and intense. And if you didn't hear Steve playing, you must have been comatose. He had a lot more ground than me.”

Vai: “Well, you gotta realize that lead singer/celebrity icons like that are a strange breed. I'm dealing with another one right now in David Coverdale of Whitesnake. And there's a certain element to each one of them. I don't know Mick like Joe does, but I perceive his persona. With lead singers of that stature, there's a certain chemical that's there from the crack of the cosmic eggshell. They're a specialized item, those people.”

Those situations unavoidably placed each of you in the shadow of great guitarists past. Just by virtue of playing a famous solo, or even by simply standing next to someone like Mick Jagger with a guitar in your hand. Comparisons with Keith Richards, Beck or Eddie Van Halen were inevitable. How did you each deal with that?

Satriani: “Well, there was a special dynamic in the Jagger band. I came in last. And I told Mick I wasn't going to cop solos and I wasn't going to set my amp up a certain way just for Rolling Stones songs. I think he knew that when he brought me into it. Plus Jimmy Ripp, who was the unofficial band leader, adopted a real Keith Richards-support role. He started all the songs, he played the five-string Telecaster. He did all that stuff.“

Vai: “Five-string Telecaster?“

Satriani: “Yeah, just take the low E off, tune it to an open G and you can play every Stones song there is. And if you want to play Stones songs right, you gotta do that. Otherwise, you sound like a bar band somewhere.

“On a six-string Ibanez, just trying to make do with the voicings, they just don't work. You have to have an open tuning. You gotta adopt the right approach, as they did, in order to get those songs to come out. But I didn't do any of that. I just came out as Joe Satriani, the lead player. I got to noodle and pump all the way through it. And I got my own solo spot – to do Midnight or Satch Boogie, depending on the shape of the show.

“So it was a bit different. If anything, it was of my own volition that I would try to play a particular solo like the record. But more often than not, Mick would look at me and go, ‘Oh no! Do what you want. Don't try to do that solo.’”

What about you, Steve?

Vai: “I couldn't worry about trying to fill Edward Van Halen's shoes. I mean, who tries to do that? When the gig came along, I knew right away that I would be compared for about five minutes. And then people would realize that Edward and I are completely different musicians.

“As for Roth, he never said, ‘Edward did it this way.’ He put no limitations on me whatsoever regarding that. Maybe on occasion I'd say to him, ‘What was it like when Edward would play this sound?’ And he'd give me his criticism or whatever. But I never felt that I was being compared in his mind, or in the audience's mind. It's the guitar player's gig of a lifetime, playing with David.”

Satriani: “There really should have been a live record. Let's call Dave up right now. Dave, where are the tapes?”

Vai: “There's some pretty wild stuff. But you know, in that band, there's more visual performance, because when I stand on the stage and play with someone like David Lee Roth, I have to wear a couple of different hats – entertainer, guitarist, etc. And I've been struggling my whole life to find the right balance between performance and guitar technique.”

Satriani: “He's such a ham. What are we talking about?”

Vai: “You know what I'm saying. I'm sloppy as shit, live. If you listen to the tracks up close, it's a mess. But there's an energy and a performance value there. You get to run around and be crazy – enjoy it and it doesn't really matter that much.”

Satriani: “I did tons of gigs where I didn't move around very much because I couldn't. There's a pole over here and wires and a monitor there.”

Vai: “Some of the best live playing I ever did was at the Armadillo World Headquarters in Texas with Zappa, where I was so sick I was passing out before the show. They had put a case carrier up on stage for me to lean my arms on, so I literally wouldn't fall over. Two two-hour shows to do on a 115-degree stage with no air conditioner! I was throwing up and practically shitting in my pants right on stage. But I stood there.”

Satriani: “The thing is they asked Steve to do that over and over again every night. He had to have dysentery for the rest of the tour.”

Speaking of audience acceptance, Joe, do you think the different musical styles on your new record [Flying in a Blue Dream] will be too much for some listeners?

Satriani: “I go back and forth on that. I'd have to answer yes and no. There are times when I wonder how people are going to get into it, other times I'm convinced that people are going to get into it because it is so diverse. But the last thought is always that I couldn't have made a different record. I had to make that record the way it came out.

“So, it's not a question of whether people are going to like it. This is the record I made. And now it's Wednesday, so you just move on from there. It is Wednesday, isn't it?”

Vai: “You know, this brings up one of my fondest memories of Joe, and one of the biggest inspirations I ever received from him. It had nothing to do with music. I had just gotten into high school, and one day just left one of my classes to go to the bathroom. The halls were really quiet. And out of a classroom I hear a teacher yelling, ‘Come back here, you!’

“Now, you gotta understand, Joe had the longest hair in the world back then. He was this weird guy with big eyes, big hair. All of a sudden, I see him walking out of this room going like this [gesture of contemptuous dismissal] towards some teacher. Like ‘get out of here.’ And he just walked away down the hall. And it was one of the biggest inspirations. It was exactly the way he's always been. No compromise.”

Satriani: “I walked out on quite a few classes. I don't know which one you caught me walking out of.”

Vai: “Well, because of that, I almost got thrown out of school.”

Were you the rebellious type in school, Joe?

Satriani: “Yeah, I guess so. But maybe in more of a solitary way.”

Vai: “Yeah, not in a destructive way.”

Do you two have any plans to record together, or have you already recorded together?

Vai: “I have a tape that we recorded together called ‘Reflections of a Year and a Half.’”

Satriani: “When was this from?”

Vai: “Don't you remember? We were at your house and you had your little two-track. We were having a lesson and I was about 13 or 14.”

Have you done any recording together since then?

Satriani: “No, not that I can think of.”

Vai: “Some of the gigs we've done together have been bootlegged.”

Satriani: “Yeah, they have. [To Vai] And, as a matter of fact, on the road I got a bootleg video of you with David Lee Roth. A hilarious thing. You see the ceiling quite a bit. Then you. Then the ceiling. It was some show where the guy was afraid he was gonna get his camera taken away from him, so he kept hiding it. But yeah, there's this huge network of bootlegs, and they've got all the stuff.”

Vai: “Getting back to the question, I've always thought about doing a record with Joe. Right now, our careers just won’t allow it because we're so busy. But one of these days, when everything dies down, we'll sit down and do it.”

Satriani: “When we've become totally unpopular. We'll probably get together. [Drops into old man voice] ‘Oh, Steve, remember the old lick…’”

Vai: “[In sappy voice] Let's call this song…‘The Sea of Emotion.’”

Satriani: “Geezers on parade.”

Vai: “It's going to be great, though. 'Cause I gotta tell you, my fondest memories of jamming are with Joe in his house when I was taking lessons. We would just sit there and jam for hours and hours. You'd just use your ears and your imagination; there were no record companies or anything like that involved.”

Satriani: “It was purely expression.”

Vai: “Those were some of the most exciting musical experiences of my life, and I want to recapture that.”

Satriani: “It would be nice to try to recapture it. But at the same time, those experiences exist because there wasn't any reason. It was just an inner need to share the expression.”

Vai: “As we mature through our musical careers, that desire to do it with no reason will come up again. And then that'll be the right time to do an album together.”

A final question. What is it that each of you admires most in the other's playing? Or what's the one thing the other guy does that you just couldn't do in a million years?

Satriani: “I've said this before. I see myself as a sort of hack in a way. I'm a quirky kind of player. But I always thought, even when I first started teaching Steve, that he possessed a couple of extra muscles in his hand [laughs]. Some more tendons maybe. Or maybe they're connected to his brain better. But there is certainly a total command I hear when he's playing.

I don't know what it is, but when Steve plays, I'm receiving another message outside of the great guitar playing that a lot of people hear

“Did you ever listen to a player and worry that he's not going to get through it? It becomes a distraction from the music. The opposite of that is when Steve's playing. It just sounds like he's got it. Everything is just what you would imagine someone could ever possibly do.”

Vai: “Fooled you guys!”

Satriani: “No. So if I had to squeeze it down into a few words, I'd just say it's the power and the impact of his playing. I've heard more of him than other people have heard. Steve Vai is a huge musician. Most people hear him as a guitar player. They don't see all the different pairs of pants he owns. But I've seen the pants and I've heard the tapes.”

Vai: “Well, thank you very much, Joe. I don't know what to say. I'll lend you my pants. I'll tell you where I bought them. Thank you, that's probably the nicest thing anybody's ever said. ‘Are you done? You can keep going if you like. Don't let me interrupt.’”

Satriani: “The only other thing I'd have to say is that there's definitely something that drew us together that has kept us together, even though there have been times in our careers where we didn't see each other for years. I don't know what it is, but when he plays I'm receiving another message outside of the great guitar playing that a lot of people hear. There's an inner message that I relate to and that draws me into his playing, and that goes beyond just guitar.”

Vai: “I said this long before Joe was popular, and I'll say it again. As long as he's making music, I'll always find an inspiration to play. I see what he does as pure integrity in music. Integrity with his own intuition. It's always been there. In the way he'd deliver himself verbally. In the way that he would walk out of a classroom and not care if he was going to get suspended. That all shows in his playing.

“For me, it isn't a matter of saying, ‘Wow, Joe Satriani: He could do the vibrato that I couldn't do.’ Or, ‘He can hit a harmonic anytime he wanted.‘ It wasn't that. It was, and is, a package. It's all part of a larger unit. Joe perceives a certain musicality in me. But I feel what I do is dwarfed by the musicality I feel coming from him. He's always been the musician, not just the guitar player.”

Satriani: “I'm all choked up, Steve.”

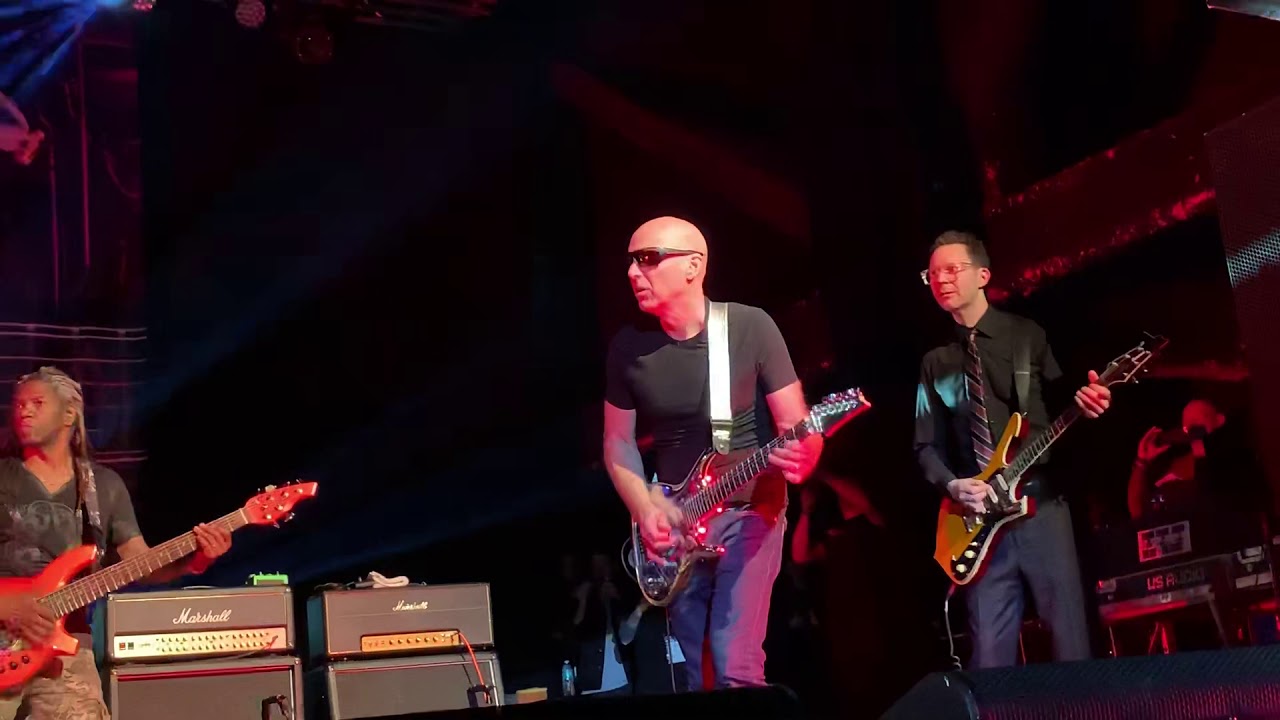

- Joe Satriani and Steve Vai are currently touring the US together. For dates and tickets, visit Satriani's website.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)