Steve Harris and Dave Murray of Iron Maiden Open Up in 1988 Guitar World Interview

Here's our Iron Maiden interview from the October 1988 issue of Guitar World magazine. The original story started on page 34 and ran with the headline, "Iron Maiden Plays the Numbers."

After eight years of knuckle-hard rockin’, Iron Maiden has released a concept album about ESP and clairvoyance, the very qualities they use to achieve their incredible guitar chemistry.

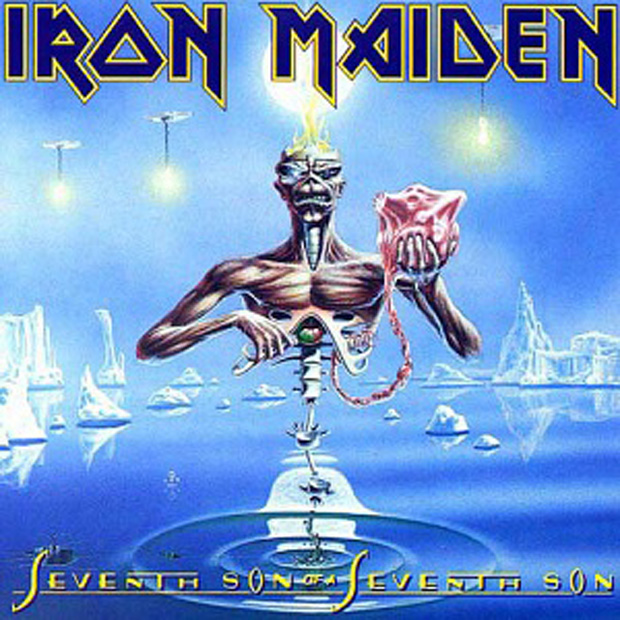

It’s called Seventh Son of a Seventh Son; it’s Iron Maiden’s seventh studio album, their seventh with producer Martin Birch; it’s the basis of a seven-month tour; there’s really seven guys in the group (you have to count producer Birch and manager Rod Smallwood as part of the action); and it was seven years ago, with the release of the band’s second album, Killers, that you probably first heard of Iron Maiden. So, we’ve covered the numbers thing, ignored 666 because it’s old and stupid and now on to the story…

In a nutshell, it was in April when Iron Maiden released its new lp, Seventh Son of a Seventh Son, a concept album dealing with the fight for the soul of the Seventh Son, some mystical chap (probably Hendrix) with the powers of ESP, clairvoyance and whatnot. Its eight (!) killer tracks were digitally recorded at Musicland Studios in West Germany, and mastered by Direct Metal Mastering for its audible sonic improvements.

The tour kicked off with an unscheduled (“and unrehearsed”) gig at New York’s L’Amour under the name Charlotte and the Harlots (Charlotte was a Dave Murray character from the band’s eponymously titled debut lp from 1980), and after stomping through Canada, the United States, Europe and possibly South America, the boys should be home spending Xmas with family and friends. The stage show is enormous, all blue, fire and ice.

Steve Harris is a boyish, good-looking chap from Leytonstone in London's East End. His quiet offstage demeanor belies the ferocity he exhibits when gripping his Fender Precision under the spotlights before a few thousand fans. He began playing when he was seventeen, late by most standards. Originally he just "messed about" with the guitar because he really wanted to be a drummer, but lacking the space to put a drum kit at home, he decided to take up bass.

A friend told him that he had to play the acoustic guitar first, and he bought one and figured out a few chords. It didn't take him long, however, to realize that this route wasn't what he wanted, and soon he shelled out forty hard-earned pounds to buy a copy of a Fender Tele bass. With the aid of a schoolyard chum and some other friends, Harris formed his first band, Influence, which prior to playing its only five or six gigs changed its name to Gypsy's Kiss. "I had only been playing about a year," laughs Harris, "and it sounded like it."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Their set consisted of a slash-through of covers like "Paranoid," "All Right Now," "Smoke On The Water," "Blowing Free," a rendition of Neil Young's "Southern Man" and such originals as "Heat Crazed Vole'" and "Endless Pit." Gypsy's Kiss soon disbanded, and Harris went on to join Smiler, covering rock-boogie stuff like Savoy Brown and early Fleetwood Mac. When Harris joined, he claims he made them toss in a few Montrose numbers and his first-penned track "Innocent Exile," but when he brought them his first "real" song, "Burning Ambition," they balked. And so did Harris -- right out of the band.

"I was only eighteen at the time," recalls thirty-two-year-old Harris, "and the other guys in the band were like, twenty-six, which I thought was really old at the time. But it was a great experience; it got me playing stuff I probably would never have played, and I had to go in and learn an entire set real quick. But I was listening to things like early Genesis, which I really love, and Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Yes, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin.

"So when I started writing my own stuff, it was with a lot of combinations and time changes and power. I wanted to do my first real song with Smiler, but when I brought it to them they said, 'Oh shit, this has too many time changes, we're not bloody doing this!' I couldn't handle that attitude, so I left and formed Iron Maiden. I still listen to all that old stuff; Foxtrot is probably my favorite record, and that's sixteen years old now and still holds up. Some of the newer bands I like include Queensryche and Marillion, and I was glad when Yes reformed. Also, Kingdom Come; I was laughing when I first heard it and going ‘This is outrageous,' but it's a really album. I went to see them play and enjoyed it."

Harris may listen to all of the aforementioned bands, but his thunderous, progressive bass style has its roots in the work of John Entwistle, Chris Squire, Mike Rutherford, Wishbone Ash's Martin Turner and Free's Andy Fraser. Entirely self-taught, he polished his chops on the tunes of Stray and Wishbone Ash, which were among the early covers done by Iron Maiden. Harris nicked a bit here and a bit there from their diverse styles, eventually developing his own distinctive and often imitated approach.

"These days, so many people come up to me and say, 'You're such an influence on me and I only listen to you,'" anguishes Harris. "I tell them that they're only going to end up sounding like me, and that they should listen to a lot of different people and cultivate bits from everybody, and then establish your own thing. That 's how I did it. I even write my songs on the bass. I play it all on the bass -- the guitar parts, everything-and then I show it to the rest of the guys. People tell me that's strange, but it's natural to me. Maybe that's what makes my stuff different, 'cause I write it all on the bass. I can't play but a few chords on the guitar, so the bass works just fine for me."

The equipment Harris uses to express himself hasn't changed much over the years. Recently, he swapped his slave amps from old, cumbersome RSD's to neat, powerful rack-mount Carvers. His preamps are four custom units called Electrons, made for him by a friend after an old 200-watt solid-state amp he once had. His cabinets are Marshall 4 x 12's with Electro-Voice drivers. A dbx compressor was recently flushed out of his system, leaving some minor eq work as all of Steve's processing. Live, he uses eight of the Marshall 4 x 12 cabinets with Electro-Voice drivers- four on each side of the drums, or, when in the studio, two cabinets and four microphones.

"The Fender Precision is my instrument, my beloved Precisions," sighs Harris. ''I've tried lots of different guitars, including some Lados, and they felt great and were really well made, but the sound just seemed to lack richness in the bottom end. My main Precision is a '71, and I also have a ‘59 that I don't use very often. I use Seymour Duncan pickups that are wound to be just like the originals which had just worn out, and I use a Badass bridge. The rest is stock. I've also had the tone control de-wired so that it's always on full treble. I did that because when we used to playa lot of gigs in England, the fans were allowed to get right up to the stage. Every time I held my bass out over the crowd when I was playing, the little buggers would turn me knobs down! I almost had the volume control done as well. Now, if I need a little more treble if the strings are getting dead or something, I just signal to my roadie by touching my shoulder and thumbing up which means top end; if I touch my ass, it means bottom end. Pretty sophisticated signaling, huh?"

Besides being the band's main songwriter, Harris also holds down half of Maiden's rock-solid rhythm section along with drum-mate Nicko McBrain. Because of Harris' secret desire to play drums, his musical relationship with McBrain works rather well. He tells a story about writing a drum intro for a song that was nearly impossible to play because of its complexity, and then making it the opening number for the drummer's first live set with the band. "He had to come out cold and play this thing his first night," laughs Harris. "Talk about framing somebody! But Nicko played it just fine."

"We sometimes have a great laugh when we're working out on songs," says Harris. "Because I can't play the drums and wish I could, I'll go in and tap something out with my fingers on the table and expect Nicko to play it. When working on that first drum intro, I kept trying to tap out this impossible rhythm and he kept trying to play it and it just wasn't working. Finally, he played it right, and I was screaming, 'That 's it, that's the one, hurry up and tape it or something!' We move pretty quick now because we're used to working together."

The second working third in Maiden's guitar team is Adrian Smith, and again, this quiet little guy's offstage presence gives little clue to the manic strut he takes on when plugged in. He also took up the guitar relatively late, at sixteen, when he met his counterpart Dave Murray. Adrian and Dave have been friends since their schoolboy days in Hackney in London's East End. In fact, Dave had been banging around on his first ax, (a Woolworth Top 20 with "a neck made of balsa wood, a body made from a washing machine and action three inches above the neck") for a couple of years before he sold it to Adrian as his first guitar (rumor has it that it wasn't working at the time).

The two formed a band and started doing school dances playing T. Rex and Rolling Stones covers "because they only had three chords."

Smith acknowledges Ritchie Blackmore and Deep Purple as his main influence, while Murray bowed to the god Hendrix and Paul Kossoff of Free. Adrian soon went on to form Urchin, and Dave did a six-month stint with an early incarnation of Maiden before rejoining Adrian in Urchin. After many genealogical twists and turns, Harris usurped Murray from Urchin to Maiden, where he was later joined again by Smith to form the twin lead/rhythm attack we know today. This fifteen-year incestuous relationship has bred an electrifying team where each man knows his gig and doesn't break the other's fingers.

Adrian and I started playing guitar pretty much around the same time; I guess we were about fourteen or fifteen years old," recalls Murray. "We would go around to each other’s house and just jam around on different songs. Over in Adrian's basement, we had this little cardboard sort of drum kit set-up with a bass drum, a tom-tom and a cardboard snare. We also had this old Vox 4 x 12 cabinet and a small amp. Once, we did this gig at a school in Hackney with a band we had gotten together, and we figured we had to make our gear look good so we covered all the stage gear with this flowered contact wallpaper made for kitchens.

"This lasted for about four or five years, and then Adrian went off to form Urchin and I knocked around in a bunch of different bands. I ended up in Maiden eventually, and when Adrian joined, it was perfectly matched, because we knew each other and had already played together. We were really into harmony guitar playing, and in Maiden there's a lot of opportunity for that. We have completely different styles, but they naturally complement each other and we lock in really well all the time.”

"It's not a competitive relationship at all," adds Smith. "There's usually two solos for each song and loads and loads of little bits and pieces, so there's never one of us who's being held back-there's always a lot of stuff to do to keep us busy. When we rehearse before we record, we play a few chords, then sit back and listen to the backing tracks and say, 'Well, you play this bit and I'll play that bit.' We sort it all out so neither of us ends up playing three solos in F#; we split everything up and make it interesting for both of us."

In the Iron Maiden biography titled Running Free, Gary Bushell notes that "those observing the two are often amazed at how well their two different styles work together. Davey's the wilder of the two, soloing off the top of his head, while Adrian is more thoughtful and tends to work his solos out in advance. Together, they seem instinctively to know what the other is up to, and make a perfect team." Recently, though, the guitarists claim that they're reversing the way they work.

"On our first few albums I used to just go in and knock off most of the solos from the top of my head by listening to the chord pattern," says Murray. "I would have a place where I started and a place where I finished, and I would just sort of go for It In the middle, just wander around a bit and see what came out. But on Seventh Son, I actually sat down with my little Fostex four-track and all the backing tracks and worked out all of my solos before I went into the studio.

"I was trying to get more of a melodic aspect to my solos instead of just ripping them out I think being spontaneous can sometime spark a little bit of magic, but I felt that this time ~t might be nice to approach the studio with everything all worked out. Actually, it felt really comfortable doing it that way, and in the future I'll probably work things out ahead of time."

"I suppose I used to sit and really try and work everything out," explains the thirty-one-year-old Smith. " But now: I go into the studio and try to do things 'a bit more spontaneously. A solo should have a special little 'thing' in it, and then I'll try and throw in a fancy bit. I find that once I work out with a solo I find the key to it and I then sort of work the rest of it around that. I can be sitting there for hours just playing around with a backing track, then all of a sudden I'll get one little bit, maybe even just a couple of notes and that's the key to the whole solo. On other songs, I can just go in and there's the whole thing, real spontaneous. Sometimes you're in the mood and sometimes you 're not. It's a funny old game soloing."

Smith does his workouts using a Jackson guitar that he's had for three years. It s modeled after a ' 55 Strat that he owns but refuses to take out on the road. The guitar sports Jackson humbuckers and the neck IS an exact copy of the ' 55. He has another Jackson Strat with a single pickup that he uses with a Roland synth set-up though he claims it doesn't sound as good as his main one, "probably because of the wiring.” A synth-equipped Lado is also in his collection, and a neck-through Jackson Soloist is being made for him that will catch up with the band on the road, although Smith prefers bolt-on models.

Adrian says he brought about twenty different axes into the studio, but ended up using just his main Jackson Strat: "It just comes up trumps every time." His amps are new-model Gaillen-Kruegers that are rack-mounted with his effects, a T.C. Electronic 2290 and a Lexicon delay. He uses 2 x 12-inch Gallien-Krueger stacks dotted around the stage for a monitoring system, the real details of which he's keeping mum about because of what might happen "once people find out I've got me own system... !" And he's even got a way to bring his studio sound to the stage.

"I've got real studio-quality effects for the road this time," he explains, "and with some help from the record's second engineer, Stephane Wissner, I can get the same sound on stage. The Germans are so efficient; he was really on the case in the studio. He wrote down every setting for every effect I used on the record and then sent them to me.

"I went through all of his notes and set about duplicating the sound on all my new gear, and now I can almost entirely recreate the sound exactly as it was on the lp. I used to just plug in and play, but now my stage presentation is going to be real technical. I'll see how it all works out, though after a couple of weeks I'll probably end up bypassing it all and saying, 'Screw it, just plug me straight in.”

Keyboards, "the kiss of death" for a heavy band, also play an expanded role on Iron Maiden's new lp and tour. Both Harris and Smith played some keys on the record, and Harris' roadie, Mike ("The Count") Kay, actually ends up onstage during the show to play synth on a couple of songs. Harris experimented years ago with a crude, early version of a bass synth, and reports that if keyboard technology had been then what it is now, he would have used them on a lot of the band's earlier material. He's right - many epic Iron Maiden songs definitely lend themselves to a wash of keyboard strings here and there.

" I think new technology, like keyboards, makes it easier to do a lot of different things," says Harris. "It also makes it easier to recreate studio sounds live. We work fairly live in the studio anyway, going in and doing songs just as we would on stage. There's not really a great deal of stuff we do on the records that we can't do live, even the keyboard parts. I never want to be in the position where we've put so much into the production of the record that there's no way we could recreate it live. It may make a fantastic lp, but then when people come to hear you play, they go, 'Great, but where's that part?"

"I like keyboards as long as they're not too dominating," adds Smith. "In a band like Saga, for example, they work great as an integral part of every song, but we're a guitar band, and we just use them for string washes when necessary. And they are necessary on some songs.”

Iron Maiden has tracked a fairly progressive course for itself, one that's steamrolled the band through nine discs and several hundred gigs, one that's earned them a rightful place alongside the industry's most virtuosic heavy bands, and is, according to its members, one that 's still gathering momentum with no end in sight.

"I think the key to our consistency lies in just growing up together and living with each other as you must do on the road," says Murray. "We've really gotten to know each other and have become very close. I also think our songs are a very important part of the whole thing, and that the strength of the band really lies in the songs. There is a definite direction for Iron Maiden, and we adapt ourselves to that way of playing. And when we're playing together, it 's that old " chemistry' thing again, where we start playing and there's a spark and the magic just takes over."

“I hope they never do one of Van Halen. I told Wolfie, ‘Make sure I’m dead’”: Eddie Van Halen's former wife, Valerie Bertinelli, rules out Van Halen biopic

“The hotshot guitar player at our gig said, ‘Your guitar sounds terrible. You should leave that thing on.’ So I turned on the Big Muff…” How a heckler helped J Mascis unlock his Dinosaur Jr. guitar tone

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)