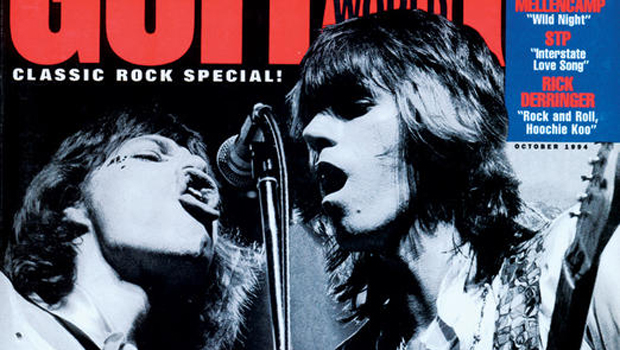

Keith Richards Discusses The Rolling Stones' Latest Album in 1994 Guitar World Interview

Here's an interview with Keith Richards from the October 1994 issue of Guitar World magazine.To see the Rolling Stones cover -- and all the GW covers from 1994 -- click here.

It’s hump time in Toronto. Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and company have rolled into town, ready to begin preparations for this year’s version of the Summer Stones. There are stage models to be examined, promotional campaigns to be mapped out, lighting schemes to be configured.

Oh yeah -- and music to be played.

“We’re getting familiar with playing some of the newer songs and stretching our memories for some of the older ones,” the 50-year-old Richards reports with a gleeful cackle. There’s nothing he likes better than playing, and there’s nobody he likes playing with more than the Stones -- though his solo band, the X-Pensive Winos, rates a pretty strong second.

“The way the shows usually shake down -- it’s kind of like picking tracks for an album. We start playing everything, and you don’t pressure or guide it too much. Some songs kind of leap out and say, ‘Yeah, me this time.’ It always comes out all right.”

These days, things are about as all right in Stonesville as they've been in a long time. The nasty mid-Eighties rift between Richards and Jagger is patched over and, seemingly, forgotten. After years of infighting, bassist Bill Wyman has left the band, replaced by Darryl Jones -- the first new Stone in 19 years. Trusted keyboard hand Chuck Leavell is on hand for the tour, and tickets -- as always -- are selling well, despite a concert market glutted by the high-priced likes of Pink Floyd, the Eagles, Barbara Streisand and the tandem of Elton John and Billy Joel.

Best of all, the new music is good. The Stones' new Voodoo Lounge is a bold, sprawling work that finds the band ignoring the sonic conventions that come with being The Stones. Oh, Voodoo Lounge has its share of Jagger-Richards crankers -- “Love is Strong," "Mean Disposition" -- but the Stones consistently reach for more, employing country touches, funk, blues, Celtic folk, Latin rhythms and lush balladry in the Jagger vocal showcase "Out of Tears" to elevate Voodoo Lounge.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"I wanted them to make the album they felt like making," says co-producer Don Was, who worked with the Stones in Ireland and Los Angeles. "My real agenda was that they write up to the level they're capable of, which really coincided with what they were thinking.

"It's easy to lapse into self-imitation; when you' re as good as they are, you can fake your way through it pretty good. They didn't want that this time."

Was, not one given to understatement, finds Richards' musicianship worthy of heavy praise. "I learned more about music working with this guy for five or six months than I could in years' worth of the Berklee School of Music," Was says. "There's certainly this conception of Keith being this drug-burnout, Spinal Tap character. It's wrong. He's a brilliant, vibrant character... a very deep guy who I think may be at the most creative period of his life.

"He plays like a jazz musician -- the way he listens to everything else that's going on and reacts to it and refuses to play organized, set parts all the way through the songs. It's not like he can't remember the parts or won't learn the arrangements; he responds to the moment. That's a really advanced thing for a rock and roll band... and a very generous way for a songwriter to approach his music."

Richards is equally generous in conversation -- cheery, sharing, easygoing. He long ago tired of some subjects -- we know "Satisfaction" came to him in a dream -- but when the subjects are the Stones and rock and roll, it doesn't seem like he'II ever tire of talking.

GUITAR WORLD: Was it different doing a record without Bill?

It's a lot easier than I thought it would be. I figured it would take us a long time; I thought it would be a more difficult process to screw around with the rhythm section. I'm kind of glad in a way that Mick and I left it to Charlie -- wisely, I think -- to name the guy.

Was it an involved audition process?

We played with a lot of good players last year; name the top 25 you can think of and then a few more. I thought life had no more surprises until we got into that! Finally we said "Charlie, for once in 30 years, you're going to be the guy to make the decision." So he went with Darryl -- another Chicago guy, as fate would have it.

I think Don Was was crushed that you didn't pick him.

[laughs] Oh, I don't think so. Actually, Don got involved on this record about the time we'd pretty much decided who it was going to be. The main thing is that Ronnie is happy that, after 19 years, he 's not being called the new boy anymore! [laughs]

What made Darryl so right?

Obviously it had a lot to do with Charlie; as I said to Charlie, "When I call down to the engine room for full steam ahead, I want reciprocation. I want the two engines going." I think the fact is that Charlie comes out of the jazz stable originally, which makes him unique in a way. That's why he swings; he makes rock and roll swing, which is one of the things you're supposed to do but many people have forgotten.

Well, the fact that Darryl spent five years with Miles Davis certainly didn't hurt. Darryl has already gotten fond of saying that the Stones is really a jazz band 'cause we improvise all the time. He tells us, "You cats do more jazz than some jazz cats I've played with." It takes the new boy to tell me I'm actually playing in a jazz band! [laughs]

But Darryl's a smooth player and very fast, and he loves his music. He loves playing with Charlie, too. To me, that's the whole key, to have a rhythm section that clicks really well together.

What accounts for the spirit of experimentation on Voodoo Lounge?

I think the Stones found their feet making this record. Not that they've totally ever lost their footing, but they were standing on one leg a bit, I think. I can only say that at the beginning of last year, when we were starting to get songs together and make this album... well, I can't say it was planned or anything. I just feel the kind of record that came out was the one I was looking for. I can't say I had much to do with it; whatever comes out tends just to come out with the Stones.

But when I listen to it now that it 's finished and realize a year has gone by, it's about as close as I've gotten to the target in a while.

In the past, when the Stones came up with some different kinds of songs or arrangements, did you ever hold back because it didn't have that "Stones" sound?

That's probably true. I think a lot has to do with the fact if that if you're just writing songs for the Rolling Stones, you kind of fall into your own little list of taboos: "We're not going to repeat this. We're not going to do that again."

But now we do work when we're not in the Stones. I think that was one of the biggest stumbling blocks we hit on the head. How long can you do this in a total vacuum without ever trying other things or getting feedback from other people? A lot of what came out on this album came from what we did in the time between the Stones stuff. When you're working with other people, you stroke a lot of other areas you were unsure of going down before. You just kind of grow, you know? It 's better than doing nothing, which was our big problem.

It's really made that much of a difference?

It has. Up until the mid-Eighties, I wasn't at all happy with the idea of the Stones splitting up. I thought one of the most important things about the Stones was that they stuck together and did their thing, and that's it. But we reached the point where you realized you can't stay inside there all the time. I wasn't going to be the first one, though; for me, I think the horror was the idea of putting myself in a conflict of interest-that if l wrote a song, should I keep it for myself or give it to the Stones? My attitude at that time was: ''This is what I worked for, so why should I put myself in that position?"

But at the same time, Mick and I couldn't just be in the Rolling Stones and do good work all the time. After two years off, we always had to wind up the giant machine. The Stones really got too big for their own good as a band; the idea of going back in and knowing we'd spend six months putting this band back on the rails again. No matter how good you are, you just don't get together after two years off and get a great rock and roll band. What you get is a load of crap.

The way things are now, I can look forward to going back there. I know everyone's been playing. It gives the Stones a chance to forge ahead instead of catching up to our past. Steel Wheels that proved it to us: in order to keep the Stones together at this stage, we do need to work outside the band as well. It's something you have to accept.

Are you conscious of the way the Stones are "supposed" to sound?

I suppose so. For a time you're aware of that. You're also aware that you're making a record once every three years, so you've got to do what you want in 11 or 12 songs, which doesn't give you a lot of room to maneuver. So you feel obliged to come up with a certain material that is "Stones" material.

I think we've been freed up a little bit from that in a way that we were freer in the earlier years. Back then we didn't care where a piece of music came from; if we liked it, we'd do it. Now we feel we can pull some more styles together. Mick and I don't feel like we have to follow our own self-imposed rules; if anything, the rule is to not follow the rules. [laughs]

When did you start putting Voodoo Lounge together?

I sat down with Mick in New York in February of '93 and said, "What are we gonna do?" We sort of had a glass of wine in his kitchen, and the only word -- and the word that counted -- was focused. We said, "If we can look down the same telescope, I think we've got a good one here." That was the real word, to get everybody focused on the same thing.

So you came up with this incredibly broad album.

True. [laughs] You say one thing and it's always another. But maybe that was the focus -- maybe the lens was broad enough that everyone can see it. To me, the important thing was -- as usual --that when I first sit down with Charlie Watts, I'll know within 12 bars. We don't have to work on the playing now or "Oh my, we're a bit rusty here," which was the case in the Eighties. When Charlie came in, the band was flying and we knew this would be easy. There's nothing like confidence.

Did the others fall in line with that way of thinking?

Oh, yes. Definitely. The sessions lent themselves to trying something different, to experimenting. When you're with a band and you're in a studio, half the time you're guessing their temper and their mettle at that time. What I found interesting about these sessions were that Charlie Watts wanted to experiment. That was a great sign; he doesn't do that very often, but suddenly he said, "Let's set my drums up in the stairwell." And I said, "Well, things are looking up!" [laughs]

The stairwell?

Yeah, on "The Moon Is Up." We were working on it and decided "Let's change the sound of everything slightly." Charlie ended up playing a garbage can with brushes, in the stairwell. I put an acoustic guitar through a Leslie amp and then miked it. Mick sings through a harmonica mike. It's a deliberate thing; "Let's make this swirl rather than just play it."

We did that on "Through And Through," too. I said to Charlie, "It's missing something, but I don't know what to do with it." He said, "I'll take my drums into the stairs," and he came up with this incredible drum sound, and we were off.

That's what you're looking for: Don't just put the formula on it, but take it out a little further and see what you can do. It's bound to change if you keep on doing things. The image changes as you change. There's not much you can do about growing up, especially at this stage of the game. I've never rushed for it, but I'll accept it gratefully now that it's got me. [laughs]

Was Don Was a help in that direction?

Yeah, Don was a great help in encouraging that extra thing; "O.K., Let's try it. Why not?" We've very rarely had producers, you know. Producers come to you, like gurus; you're not supposed to find them, they find you. Not that one ever found me, I must say. [laughs]

Anyway, to me, working with Don was very reminiscent of working with Jimmy Miller, and you can't ask for better than that. He's also a musician and is not only respected by the band for the technical end of doing the job, but he has a very natural feel with the guys. There wasn’t this impression that somebody here is producing the Rolling Stones; you're making a record with him.

That's an important barrier to break down with the Rolling Stones; they can sense when somebody is thinking, "Oh, it's THE STONES" -- that slight unsureness and intimidation. What we look for is someone who knows what they're going for. Don did that. He was not impressed with any star crap, which is what's most important to us at that point.

Let's get down to some brass machine heads on this album. What's the "mystery guitar" you play on "You Got Me Rocking."

Aha! The mystery guitar will no longer be a mystery if l tell you. [laughs] What the hell... It's a solidbody dobro, but I play it with a stick -- just a little stick I picked out of Ronnie's garden. It's just an interesting percussion effect.

Were the guitar parts mapped out during the writing process?

No, not really. The songs kind of suggest themselves, and the arrangements and the parts almost flow from the moment you lay down a bare bones of songs and throw it around amongst the guys. A shape kind of takes place that's natural. I always try to grab that, especially when we're cutting the rhythm tracks.

You really just keep an ear and an eye on everything that's being played and you remember it. What I don't like to do when making record within bands -- especially small bands, rhythm sections like the Rolling Stones -- is to try to impose anything. If you tell somebody how to play something, you've automatically got a certain stiffness into it: "Oh, he wants me to play that." I'd rather have them do it as they feel. The less you talk about it, the better it is. When you get a good playback, nobody says anything; you just nod at each other.

For instance?

Probably "Love is Strong." That's the band; sounds like 'em every time. We didn't have to fiddle with it at all. You just try to find what feels natural for the song … Just lay the guitars down and do as many parts as you like. In the mix you can use a bar of it here, a bar of it there. When you're listening to basic tracks, you're listening to what's not there and for what should be there. You're following some little picture in your mind or in the ear that says "That's funky, but it needs something that rings a little bit at the top."

If you've got the songs, you can overdub as much as you like. You have to be judicious in your editing and mixing. It's what Ronnie and I call the "ancient art of weaving."

Don Was likes to refer to you as a pitcher, someone who tosses out ideas and lets the band bounce them around. Is that a fair assessment?

Working with drummers like Charlie Watts or Steve Jordan and Charlie Drayton in the Winos, that's all I need. I can throw riffs at them all night; when the drums catch on, I know there's something there. My strength, probably, is I can recognize a song in a few bars. I spot the embryo there. I've been writing since so early on that the antenna is really well-developed. If I pick up an instrument, it'll come to me. I don't go searching. I don't have that God aspect about it. I prefer to think of myself as an antenna. There's only one song, and Adam and Eve wrote it. The rest is a variation on a theme.

There's actually a ZZ Top-quality to "You Got Me Rocking."

There could be. I haven't heard ZZ Top for a long time. Apart from the fact that we both play rock and roll, the comparison wouldn't occur to me, but you never know. We all cross over. I know that to me the rhythm has a bit of Motown, like "Goin' to a Go-Go," [Smokey Robinson And The Miracles] a little funky. I was looking for a swampy rhythm, something punchy. Wrote the thing on piano and then transferred it over to guitar.

There's a lot of B-bender guitar on the album. A new fetish?

I wouldn't call it new. [Late country guitarist] Clarence White invented the thing many years ago. It's a guitar with a special job on it: you pull on the neck and the B string bends and gives you a pedal steel effect. Jimmy Page uses it quite a lot and Ronnie works on it. I use it now and again. It gives you a nice guitar feel, a little pedal steel but also a little slide. It's another tone to play with. The only trouble is, if you play it... the whole thing goes out of tune. You have to do a little training to play it.

Has your musical relationship with Ronnie changed markedly since 1975?

Ronnie and I, we've had a ball for the last year. He says, "Thanks for some good songs to play," and I'll say, "Thanks for being there to play them with." There's nothing you can put your finger on and say, "We did this at his time and that's why it's better." It's just about playing with somebody, and every time you get down to playing you're testing each other more. Ronnie Wood is an amazingly sympathetic player; he'll get to the root of what you're on almost straight away.

You even managed to get Pierre [de Beauport] a credit on the album.

He works for me; he's my guitar man, mechanic, and a damn good player, too. He happened to be the only guy around that night, and he's been with me from when I first came across that song. We cut the first demo of it together, so I thought he deserved to have his mark on it. As we were finishing the record, I said, "Pierre, by the way, your acoustic's on." He said, "You've got to be kidding!" I told him, "No, go for it."

What were your considerations for the show this year?

I'm looking to balance it up. As you can imagine, the show will kind of change and incorporate more of the newer numbers after the record comes out and we get some feedback. I'd like to do as many of them as we can. First off, the songs are made for the stage -- they're dying to be played live. Also for this show, I'm not trying to get too stuck to a set list. In the past we've had one song changing here, one song changing there, which is almost the same. But it's difficult to change a lot on these great big tours, with everyone locked into their computerized lights. We try to rehearse far more stuff than we actually need so we can vary the show from night to night if we want to.

The other thing is I don't want to repeat the big band revue sort of feel of Steel Wheels. -- I want to strip it down a bit. I want to discard that revue feel; the five Stones and 11 other people. We, the band can do a lot more within ourselves.

You enjoy referring to the Stones as a juggernaut, which is pretty accurate. Do you ever wish you play smaller venues?

That's heaven and hell together, and you can't have it all. We have to work within the Stones' standards. I mean, it would be great; this band can play a club better than any in the world, probably. That's where it sounds best. But it's gotten this big, and you've got to deal with it.

Plus, it's very unlikely anyone will go for it -- like the police or the promoters. They say, "I don't want my club ruined." Or if everyone else wants it the police department says, "We can't allow the Rolling Stones to play in our High Street in a little club. There'll be a riot." There's so many imponderable things to get through. Unless it's a one-off... you're fighting against nature.

That doesn't mean we won't try, though. [laughs]

Have you noticed the strong regard for the Stones that exists within younger bands now? The last time there was this kind of influx of new music, it was 1977 and everybody slammed you.

It's probably more just a matter of fashion and timing. In the Seventies, those guys who were coming up were 10 years younger than us. We were like their big brothers who used to rub their noses in it, so there was a natural rejection and rebellion there. Now it goes around full circle; maybe it's just because we're still here. But I know loads of guys in new bands, a lot of kids on the road who are players. There's a lot of 15, 14-year-old boys out there with their Fenders in their hands, which is great. There are worse things you can do in this life than that.

Any thoughts on Kurt Cobain?

I wasn't really too aware; I didn't even know the name of the lead singer of Nirvana until that thing in Rome went down. I heard that and thought, "He was lucky this time." I was just astonished that two weeks later…no one was keeping an eye on him and just let him buy a shotgun. Mick summed it up well; he said it was inevitable. It would have taken a few years longer to do if he hadn't been famous. It just wasn't the right job for someone of that temperament. People say: "What's so tough about being the lead singer?" But if life was so difficult for him there, it would be appalling anywhere else, wouldn't it?

When you were that deep into drugs, did you have people keeping a better eye on you?

Yeah, somewhat. But they also knew I wasn't looking to top myself. There's a difference between scratching your ass and tearing it to bits, you know.

So what is a Voodoo Lounge?

It's wherever I hang out. [laughs]

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)