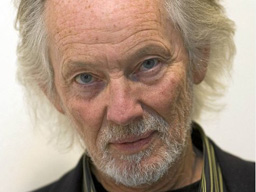

Klaus Voormann Discusses His Lifelong Musical and Artistic Association with The Beatles

From a chance encounter with the Beatles in Hamburg, he forged a friendship and musical partnership with John Lennon that lasted two decades. In a rare and extensive interview, Klaus Voormann provides an intimate look into Lennon's solo career and artistry.

Klaus Voormann holds a special and uniquely privileged place in the story of John Lennon and the Beatles. He befriended the Beatles several years before their rise to fame, when they were still a struggling bar band performing in Hamburg, Germany.

A German-born musician and visual artist, Voormann made significant contributions to the Beatles’ image and look. After the band split up, he went on to play bass on numerous solo albums by John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, essentially stepping into the instrumental role once filled by Paul McCartney.

“But I never looked at it that way,” he says. “When I was first asked to play with John, I couldn’t believe it. It was just mind blowing. But as soon as it came down to the actual playing, this great happiness came into my heart. The whole thing was like a dream, like it wasn’t really happening. From then on I never thought, Oh, how fantastic I am, I played with these famous people. That was out of my mind. I never thought of it. They were my friends. They wanted me to play because they liked my playing. I was lucky to be in that situation. That’s all I can say about it.”

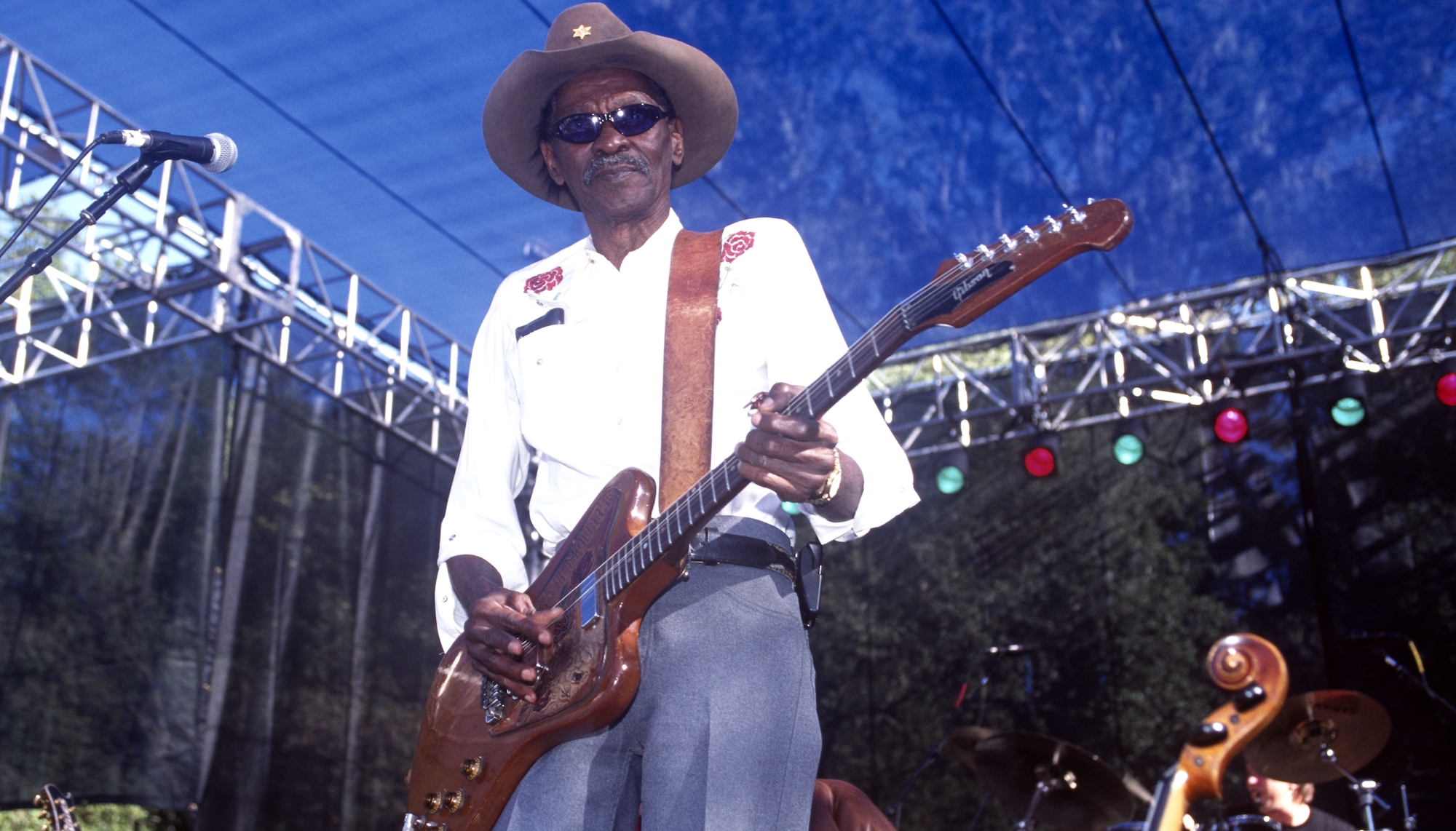

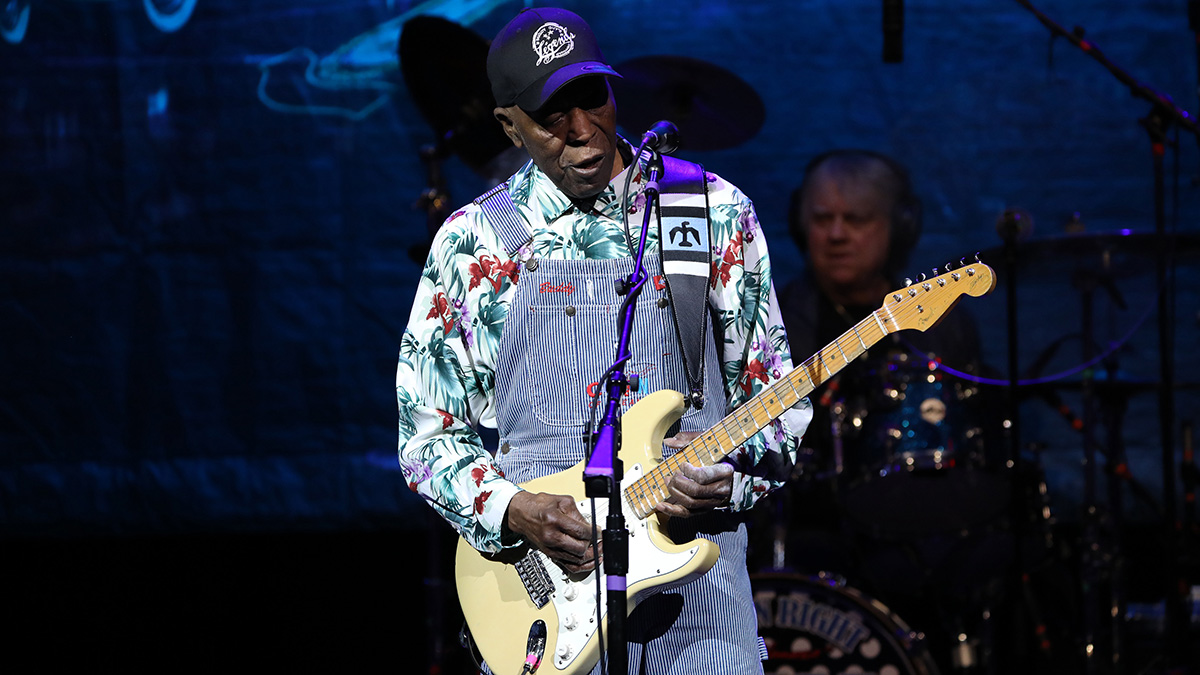

Soft-spoken and gentle in manner, Voormann is the ideal sideman: unassuming, unfailingly upbeat and focused on his work with characteristically Teutonic seriousness and sincerity. These qualities have served him well in his contributions to not only ex-Beatle solo albums but also many other hit records and legendary recordings. He’s on Lou Reed’s Transformer, Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain,” Randy Newman’s “Short People” and Manfred Mann’s 1968 hit recording of Bob Dylan’s “The Mighty Quinn” (on bass and flute). Not to mention discs by B.B. King, Harry Nilsson, Jerry Lee Lewis, Howlin’ Wolf, Leon Russell, James Taylor, Peter Frampton and many others.

The fortunate trajectory of Voormann’s life and career was set in motion one evening in Hamburg in 1960. Walking off an argument with his girlfriend at the time, Astrid Kirchherr, he ventured down a street in Hamburg’s red-light district, the Reeperbahn, a precinct crowded with rowdy bars, strip joints and prostitutes in shop windows soliciting passersby. Voormann heard a sound that stopped him in his tracks outside a bar called the Kaiserkeller.

“Through a window I heard rock and roll music being played live,” he recalls. “It was the very first time that I’d heard live rock and roll music, and it turned out it was the Beatles, although I didn’t know that at that moment. The second band that was on that night was Rory Storm and the Hurricanes with Ringo Starr on drums. When I went into the club, that was the band I saw first. I thought they were great, especially Ringo. And after they played, the Beatles came up onstage. It was absolutely amazing. I’d never seen or heard anything like that in my life.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

At the time, the Beatles lineup consisted of John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison all on guitars, with an art school friend of Lennon’s named Stu Sutcliffe on bass and fellow Liverpudlian Pete Best on drums. The Beatles were a copy band in those days, recently arrived in Germany from Liverpool and cranking out a lively repertoire of Fifties rock and roll songs by artists like Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino and others, mixed with a smattering of standards and sappy ballads.

Prompted by Kaiserkeller owner Bruno Koschmider, they’d developed an aggressive style of stage performance gauged to catch the attention of the bar’s roughhouse clientele. And they’d learned to keep the music pounding even as drunken fistfights and all manner of grievous bodily harm broke out on the dance floor.

It was all a bit overwhelming, but profoundly appealing for Voormann, a quiet and sensitive young guy who’d already begun to make a way for himself as a commercial illustrator. On these visits to the Kaiserkeller, he started to bring along his artsy, bohemian circle of friends, including the aforementioned girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr, a stylish, blonde photographer and clothing designer, as well as another photographer, Jürgen Vollmer.

Collectively they were known as the “exis,” a take-off on the French existentialists who, inspired by the work of writers like Albert Camus, Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, had fashioned a kind of bleak chic from a philosophy regarding life as essentially meaningless and absurd. Voormann’s crowd dressed mainly in black suede, velvet or leather, men and women alike wearing a kind of unisex hairstyle that Kirchherr had pioneered.

In contrast, the Beatles at the time were sporting a Fifties greaser, or Teddy Boy, look, with tight trousers, pointed “winklepicker” shoes, and hair slicked back on the sides and cascading forward in a pompadour that hung dramatically over the forehead. It was a more working-class aesthetic. Yet the Beatles and the “exis” shared one very important quality: they were outsiders, two distinct yet similarly alienated subcultures that just had to get together. And Voormann forged the first link.

“The first Beatle I talked to was John,” he says. “One night at the club, my friends said, ‘Come on Klaus, you can talk some English. Go and talk to the band. We have to make contact somehow.’ So I took a record cover I had designed for a Ventures song called ‘Walk Don’t Run.’ I went up to John and showed him that. And he said, ‘Go show that to Stuart. He’s the artistic one in the band.’ So he pushed it off, like, ‘I’m a rock and roller now. I’m not doing art anymore.’ ”

Sutcliffe and Voormann became fast friends, despite the fact that the Beatles’ then-bassist became the new man in Kirchherr’s life, handily ousting Voormann. As if in recompense, Sutcliffe bestowed what proved to be a very valuable gift on his German friend.

“One night I came into the Top 10 Club in Hamburg, where the Beatles were playing,” Voormann recalls. “Suddenly Stu just handed me his bass. I had never had a bass guitar in my hands. He said, ‘Come on, you play now.’ And the rest of the band said, ‘Yes, come up onstage.’ I said, ‘No I can’t do that. I’m scared.’ So I sat in front of the stage, took a chair, put it in front of the stage and started playing the bass. I’d tinkled around on a guitar a little, but really I had no idea. I knew fourths, what the strings were. And then the first song was counted in. It was a Fats Domino number, ‘I’m in Love Again.’ And that’s the first time I ever had a bass guitar in my hands.”

The episode would prove a harbinger of things to come. Shortly thereafter, Sutcliffe left the Beatles, remaining in Germany to live with Kirchherr and pursue his vocation as a painter. McCartney, of course, took on the job of playing bass with the Beatles, and Sutcliffe sold his Höfner model 333 bass to Voormann. “He wanted to buy paints,” Voormann says. “He didn’t want to play anymore. So he needed money.”

The Höfner bass that Sutcliffe initially encouraged Voormann to play, and eventually sold to him, set Voormann on a road that would bring him onstage and into the recording studio with some of the most celebrated musical artists of the 20th century and beyond.

Voormann is also the first man to have sported the legendary Beatles haircut. The style had been originated by Kirchherr, again in emulation of French bohemians. She did her own hair that way, and then Voormann’s—a daring subversion of fashion as a signifier of gender distinction. Today, it’s impossible to convey how radical it was for a man to comb his hair forward in bangs and let it grow over his ears. Stu Sutcliffe was the first member of the Beatles to embrace the look, requesting that Kirchherr style his hair in the same way she had done Voormann’s. One by one, the other Beatles—except for Pete Best—summoned the courage to follow suit. When Best was fired and Ringo Starr took his place, the new drummer likewise let Kirchherr cut his locks.

This German hairstyle—along with Italian boots and close-fitting suits with colorless jackets—was part of the look that Brian Epstein fashioned around the Beatles when he took on their management in 1962. Much to the chagrin of the Beatles, their hairstyle and clothing were almost as much a factor as the music in their phenomenal ascent to worldwide fame in late 1963 and 1964. This is something that would come to frustrate Lennon greatly.

The Beatles didn’t forget their German friends once they achieved worldwide fame. Around 1964, Harrison and Starr invited Voormann to move to London. They even put him up in a London apartment they shared as Voormann got a start in Britain’s capital, landing a job at an ad agency. He found that fame had not altered his friends to any great degree.

“They stayed very much the same,” he says. “It’s only the circumstances they were now in that made them live a different way. And of course John was married by then [to his first wife, the former Cynthia Powell]. John was always very nice. He was very subdued. When he was private, he wasn’t so outgoing. But of course he was very funny and could express himself really well. By ’64 they were starting to become aware that every word they said would be picked up by the media and judged by the public. And of course that eventually got John in trouble.”

Beatlemania put serious constraints on all the Beatles, impinging on their private lives by seriously restricting their ability to travel and go out in public for fear of being mobbed. But, as Voormann observed, stardom seemed particularly taxing for Lennon. “Of all of them, I think John was the most unhappy, mainly because he constantly had to do stuff. He had concerts to perform and obligations to fulfill, and he didn’t like that. George was also unhappy, but in a different way. He didn’t like the public. That’s what people don’t really know. George didn’t really enjoy being in front of the people.”

Lennon particularly hated the performance turn in which he and McCartney or Harrison would stand face-to-face in front of a mic and wiggle their heads as they sang one of their trademark “ooooo” falsetto backing vocals. “When you see him doing it on the videos, you can see he’s really making a joke of it,” Voormann says. “John felt sad that there was a crowd out there that reacted to little stupid gestures in such a way. He didn’t like the power that he got being a Beatle. It wasn’t till he met Yoko that he learned how to use that power to try to do something good in the world.”

Voormann soon had made his own foray into the pop group scene as one third of the trio Paddy, Klaus and Gibson, which was managed by the Beatles’ own Brian Epstein. Beatles trivia buffs may recall that Paddy, Klaus and Gibson were the group that Lennon and Harrison went to hear on the very first evening they dropped acid, in 1965, although Voormann doesn’t recall many details from that evening.

While Voormann’s musical career was underway, he found time to accept an offer from Lennon to create the cover art for the Beatles’ landmark Revolver album in 1966. “John called me and said, ‘How about doing an album cover?’ ” Voormann recalls. “‘Why don’t you come to the studio, listen to the music, then go home and see if you have an idea. And if you have a good idea, you got the job. If not, you don’t have the job.’ So I went to the studio and everybody was there. I listened to the songs, and I was floored. It was so amazing. You simply can’t imagine what it was like at that time in pop music to go so far out there and do a song like ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ with all kinds of tape loops and wild sounds.

“But everybody was worried that this was not the right material to approach their fans with. And that was my problem in doing the cover art. I went home and racked my brains: What can I do that is somehow leading into the future but still is something that the normal fan goes for? I made some different sketches and showed them to the band. The one with the hair and the little figures was in there as a sketch. Everybody loved that one. I loved that one too, and I knew they would go for it. I was happy because I had the job and I could do the cover.”

In his unofficial role as the Beatles’ art advisor, it was Voormann who recommended Swedish director Peter Goldman to create the supremely trippy video for the Beatles’ masterpiece “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Voormann remembers the shoot, which took place at Knole Park, outside London, as one of several occasions on which Lennon confided to him his unhappiness in his marriage and career.

“John was not in good shape. He was very unhappy. He was living in Weybridge at the time [his house outside London] and he didn’t like to be with Cynthia, his wife. The whole situation, the whole setup—he didn’t enjoy it. I mean, he was always frustrated. Till Yoko came along, John was frustrated. He was very sarcastic, very funny, like a clown sometimes, but he was always frustrated.”

As Voormann notes, deliverance for Lennon came in the form of Japanese avant-garde artist Yoko Ono. The couple first met in 1966 and were married in 1969, shortly after John’s divorce from Cynthia was finalized. John and Yoko embarked on a series of high-visibility Bed-Ins for Peace and other public happenings that combined politics and avant-garde art.

Voormann was drawn into this exciting new world of Lennon’s in September 1969 when he was asked to join the guitarist for a gig at the Rock and Roll Revival Concert in Toronto. On a whim, Lennon had decided to accept a last-minute offer to share a bill with the rock and roll heroes of his youth: Bo Diddley, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. Lennon hastily assembled a band 24 hours before the show, calling on Eric Clapton—with whom he’d recently performed on the Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus TV special—Voormann and drummer Alan White, who would later go on to be a member of Yes. The group would appear under the name Plastic Ono Band, a moniker Lennon and Ono had come up with for their projects and which had first appeared on the couple’s 1969 single “Give Peace a Chance.”

“John asked me if I would do it, and I paused because I couldn’t believe what he was saying,” Voormann recalls. “He would always get very uptight when you were not immediately like, ‘Yeah, that’s great! Sure I’ll do it!’ I paused a little and said, ‘You’ll have to explain this a little to me. I have no idea what the Plastic Ono Band is. Is that Yoko’s band? Do we have to go naked onstage or what?’ I had no idea in my mind. Suddenly it was not John Lennon; it was the Plastic Ono Band, so I knew it had something to do with Yoko. And he explained to me, ‘I want to go in the studio and record together, and I want the band to play. Eric said yes already. How about you?’ I said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’”

The hastily convened ensemble rehearsed acoustically on the plane from London to Toronto. This was to be the first live rock concert Lennon had performed in about three years, and his first without the Beatles. Backstage, bravado gave way to stage fright. “John was very, very nervous,” Voormann says. “He had no idea what was coming. He’d never played with Alan White before. We hadn’t really rehearsed. So as we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys, hang on!’ And he went in the corner and vomited. Okay, it was partly the drugs he was taking, but partly it was stage fright.”

Of Lennon’s decision to perform the show, Voormann says, “In one way, he was saying, ‘Oh fuck it, let’s do it. It’s fun.’ But suddenly he realized, ‘My God, I’m John Lennon. I was with the Beatles and now I’m going out there with a band—no rehearsal, no nothing. Just play some old rock numbers. Is that really the thing to do?’ But he pulled it through, somehow.”

It’s interesting to compare the Toronto performance of Lennon’s song “Cold Turkey” with the studio version, recorded less than two weeks later. In that short time, what had been little more than a sketch evolved into a chilling, stark arrangement that masterfully reflects Lennon’s harrowing lyrical account of his recent, painful withdrawal from heroin addiction.

“I was very frustrated on the plane from London to Toronto because I knew we couldn’t do justice to the song with no real rehearsal,” Voormann says. “I thought, Shit, what a great song. We really have to rehearse this properly and make something of it. But when we went onstage, we just played the chords. It was silly. It was just spur of the moment.”

But Lennon, Clapton, Voormann and White got their opportunity to hone the arrangement over the course of 26 takes of the studio version. “We tried several things,” Voormann says. “And when I came up with that bass line that you hear on the record, and the guitar answered, that was it. Suddenly it was haunting. It somehow had this cold atmosphere. We actually doubled my bass part. When you put on headphones, you can really hear it. You hear these slight fluctuations, because I actually played the part twice; it wasn’t automatically doubled. It makes the part a little disquieting. It doesn’t really feel good. It was supposed to be like that.”

Like much of Lennon’s early solo work, “Cold Turkey” is remarkable for its sparse, dry, minimal feel. Only a small part of what was laid down on tape made it to the final mix. “John and Eric played so many guitar parts,” Voormann recalls. “The whole 24-track tape was just filled with guitars all over the place. Till in the end they decided on the two guitar parts you hear in the final mix, and it was fine.”

Voormann recalls that the chemistry between Lennon and Clapton was very positive. “I would say that Eric felt like a servant to John, because he loved John so much. Eric did not behave like a star or anything. He was just a good guitar player. That’s the way he acted. So they got along really well.”

The late Sixties had given rise to the “supergroup” phenomenon—all-star ensembles featuring top players from multiple legendary bands. Clapton himself had been part of two such super-groups, Cream and Blind Faith. The Lennon-Clapton combination seemed full of potential: one of the hottest guitarists of the day, together with one of the era’s foremost songwriters and frontmen. But this was never to reach fruition. Lennon and Clapton went their separate ways soon after the “Cold Turkey" session. “Eric had his own thing,” Voormann says. “I don’t think he would have stayed on. The whole thing fell apart pretty soon. It wasn’t like, ‘We are the band. We stay together.’ It wasn’t organized, anyway. ‘Nobody around us was saying, ‘Oh, you’re the band now.’ And I never thought that that would happen either.”

It was, by design, a very minimal ensemble that joined Lennon in the studio for his revolutionary first solo album, Plastic Ono Band, in 1970. The disc reflects the encounter Lennon had recently had with psychiatrist Arthur Janov’s Primal Scream therapy, making it the treatment’s aural equivalent. Listeners hear him stripping away all the defense mechanisms and coping strategies that get us all from one day to the next, confronting his deepest and most painful psychological issues head-on. And for the most part, it was recorded with just a small, intimate circle of players: Lennon on guitar and piano, Voormann on bass and Ringo Starr on drums. The history between the three men went all the way back to Hamburg, and the result was a deep, intuitive connection.

“John simply felt that those songs were very immediate and spontaneous, and we wanted the recording to be just as spontaneous,” Voormann says. “We all know there are lots of mistakes on it. But Ringo and John together are amazing. I just played along with them, and it was great. We fitted together really well. I’d never played with Ringo before. And very little with John.”

Also present as coproducers were Yoko Ono and Phil Spector, the notoriously temperamental architect of classic mid-Sixties “wall of sound” hits by the Ronettes, Righteous Brothers, Ike & Tina Turner and others. Spector had stepped into a production role with the Beatles just as the group was disintegrating and remained in place as producer of Lennon’s early solo work. Despite Spector’s reputation as an eccentric and hothead, Voormann says the producer was exceptionally well behaved during the making of Plastic Ono Band and its 1971 successor, Imagine.

“Phil was very subdued and cooperative,” he says. “He was helping a lot. He listened to what Yoko was saying. He never had a fight or disagreement with Yoko. They got on really well with one another. He was really listening and making a great sound. Look, I’ve seen Phil get crazy and all that. But during John’s sessions maybe there was too much admiration on Phil’s part. He was not going to do the wall of sound. He was not going to go crazy. He just did the job and did it well. He was really loving all the songs. Sitting at the piano, he knew all of John’s songs. He learned them all.”

The affable Voormann has always enjoyed a good relationship with Yoko Ono as well. “I always got on with Yoko,” he says. “She’s very sensitive. You wouldn’t believe it. I remember once in Berlin I met her. I came over. I had other things to do and was maybe a bit preoccupied or disturbed or whatever. And years later, she was still saying, ‘Klaus, you were not nice to me that time in Berlin.’ She doesn’t forget those things. And sometimes she can be very abrupt and very hard. Makes people feel bad. But in another way she’s the loveliest person you could imagine. She’s very inspiring, very excitable and enthusiastic about things.”

For Lennon’s landmark Imagine album, the scene of recording shifted to a studio the artist had put together at Tittenhurst Park, the idyllic home outside London that he and Ono shared. “It wasn’t a huge house like George had, with 80 or 90 rooms,” Voormann recalls. “It was just two floors, upstairs and downstairs, and not many rooms. The studio was really small. It was just a bedroom. It was John’s bedroom made into a studio. I think he and Yoko slept upstairs. But it was a beautiful place. The guy who originally owned or built the house knew all about trees. He knew exactly where the water was coming and which type of tree would do well in each part of the property. So it was a really great park, beautiful. I don’t know what it’s like now. No idea.”

Lennon worked with a larger group of players than he had on Plastic Ono Band. Voormann was once again on bass. But this time, the great rock session pianist Nicky Hopkins, who played with the Who and the Rolling Stones, was on hand to lend his inimitable touch to several tracks, including the ragtime-flavored “Crippled Inside,” Lennon’s scathing put-down of bigots, conformist and sundry other uncool types. George Harrison played guitar on Lennon’s bitter, anti-McCartney diatribe, “How Do You Sleep?” and drummers Alan White, Jim Keltner and Jim Gordon (fresh from Derek & the Dominos) contributed to various tracks. A string section, the Flux Fiddlers, was overdubbed onto some songs. With characteristic self-deprecation, Lennon would later dismiss the album’s production as “candy-coated.” But Voormann, like many others, disagrees with this assessment.

“With some songs the big production really works,” he says. “ ‘Jealous Guy’ was a great song even before they put strings and other things on it. I love the way we all played on that. John’s singing is great. But some of the songs on that album would not have come off as good if we had tried to do them just as a trio—‘Crippled Inside,’ for example. That’s one where I played upright bass, only I had no idea how to do slap bass. So Alan White came up and said, ‘Okay, I’m going to play the drumsticks on the bass string. You just hold the notes.’ So we did that while Jim Keltner played the drums.”

Voormann remembers Lennon as a disciplined and organized—yet generous and open-minded—session leader. “John had all the songs ready to go. He’d give us a lyric sheet with the text of the song written in big letters, about half an inch high. He’d go to the piano or take the guitar and play us the song. And he’d tell us, ‘Here it goes to F#.’ So we wrote the chords underneath the words. He played it once, we’d rehearse maybe two times, and then we recorded. John would never tell me what to play. I always played what I wanted, and he accepted it.”

Voormann worked less with Lennon after he and Ono moved to New York in 1971. But he did witness some of Lennon’s notorious mid-Seventies Lost Weekend, when the rock star separated from Ono and went on a protracted drunken binge in L.A. with fellow elbow-bending celebrity musicians Keith Moon, Harry Nilsson and Ringo Starr. “Everybody knows that Harry and John were totally gone,” Voormann says. “Didn’t have a clue where they were most of the time. But that was when my first son was on the way, and I was spending a lot of time with his mother. So I was really doing other things.”

Which is perhaps why Voormann did not actually play on the disastrous first set of sessions for Lennon’s Rock ’n’ Roll album in Los Angeles. Lennon had agreed to record an album of classic Fifties rock and roll songs to settle a legal dispute with legal publisher Morris Levy. But the album sessions with Phil Spector fell apart amidst scenes of drunkenness and gunplay. Finally, Spector absconded with the master tapes.

“If it was a song that John wrote, he would know exactly what he wanted to do,” Voormann says. “But in this case they said, ‘Let’s take an old rock and roll song, and you do it, John.’ And I think he couldn’t handle that for some reason. Maybe it was because he was flipping out or whatever it was. But for some reason he couldn’t handle it. So they gave up.”

Lennon returned to New York in 1974 and started to get his life back together. Voormann joined him for the making of the Walls and Bridges album released that same year. Not one of Lennon’s greatest efforts, the album is mired in a production aesthetic that all too vividly evokes pastel polyester leisure suit Seventies jive. (Lennon produced the album himself.) The sound and style seem ill suited to Lennon’s angst-laden lyrics born of his unhappiness at being separated from Ono. Still, the unlikely juxtaposition did produce Lennon’s only number-one hit as a solo artist, the duet with Elton John, “Whatever Gets You Through the Night.”

Voormann loyally declares Walls and Bridges “a really underrated LP. There are some great songs on there. You see, the atmosphere in the studio was very similar to the making of Imagine. John was sitting there playing the guitar. We would listen to the songs. But maybe that’s just my perception. I’m always so focused on the feel, the guitar playing and what the drummer is doing that I might not notice anything else that might be going on in the studio. I just want to do a good job.”

The bassist recalls helping come up with the idea for the slow orchestral interludes in “#9 Dream,” one of the better Walls and Bridges tracks. “John played the song for me and said, ‘I don’t know, there’s something missing. The song doesn’t feel quite finished.’ I sort of said, ‘It’s a very dreamy song. What if John stops and there’s some kind of melodic part?’ That’s what he did, and the song’s great.”

Shortly thereafter, Voormann joined Lennon in finishing up the troubled Rock ’n’ Roll project, which was released in 1975. “We went up to Morris Levy’s house in upstate New York and rehearsed with Jim Keltner, Jesse Ed Davis and all these people who are on the album. It was a really good rehearsal, and we were able to get the album done.”

Voormann’s playing career with Lennon ended as it had begun—with the Fifties rock and roll classics that had shaped both men’s destinies. Shortly after Rock ’n’ Roll was released, Lennon reunited with Ono and went into a period of retirement, withdrawing from the music business to concentrate on raising his son Sean. The last time Voormann saw his old friend was at Lennon and Ono’s home in the Dakota apartment building in Manhattan.

“I have photos of that visit,” he says. “Sean was already five years old, maybe even older. I went to see them in the Dakota and we had a great time. I went in the kitchen and John was baking bread and cooking rice. He showed me how to cook rice. We were just hanging out in the kitchen. He was playing a little guitar and Yoko was doing some sushi. So it was really family-like. John said to me, ‘Klaus, I’m so relieved. I don’t have to do any more recording. I don’t have any record deals.’ He was happy he didn’t have any of those obligations. Although he still picked up the guitar.”

Of course Lennon did return to recording and public life in 1980 with the release of Double Fantasy. And the question that haunts every Lennon fan is whether John would still be alive today if he hadn’t gone public once again, attracting the attention of a homicidal psychopath. In the time since Lennon’s passing, Voormann has remained friendly with Ono, who helps Voormann and his wife, Christine, in their charity work to benefit the Native American Lakota people of South Dakota. He even joined Ono, Clapton, Keltner and others in a Plastic Ono Band reunion concert in January 2010 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Klaus Voormann treasures his memories of his longtime friend. And, like everyone else, he treasures the music.

“John’s great strength was his ability to put into words feelings that so many people can relate to,” Voormann says. “Not many people, if any, can write songs like that. Who can find words like that? John even invented his own words. And he had a message to put across. That makes beautiful songs.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“Stevie came to my 5th birthday and gave me a pawnshop Harmony. It didn’t have a gig bag, it had two paper grocery bags on either end”: Tyrone Vaughan descends from blues greatness – and SRV helped him start his guitar journey early

“Live right up to the last breath and stay positive about the world, your family and the environment you live in”: Mike Peters, frontman of the Welsh band, The Alarm, has died aged 66