This 1994 interview with Hubert Sumlin is reprinted from Guitar Legends: Blues Power

“Wolf and I had some tremendous fights. He knocked my teeth out, and I knocked his out.”

“I never used a pick again—that was my secret to unlocking everything.”

“Clapton said, ‘If Hubert’s not there, I don’t record.’ ”

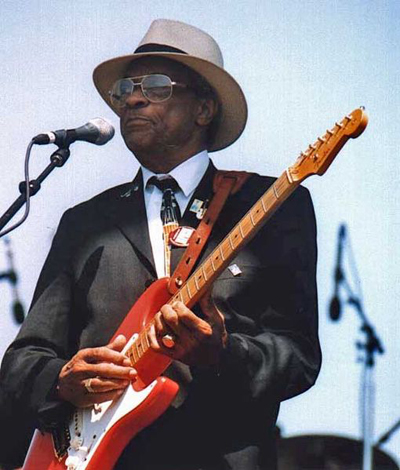

Few musical marriages have been so magical, so intuitively right, as that of the great blues singer Howlin’ Wolf and his guitarist, Hubert Sumlin. From the time he joined the blues legend’s band in 1954 until Wolf’s death in 1976, Sumlin played a central role in crafting some of the century’s most memorable and influential American roots music. His economical, stinging fills, unusual rhythmic approach and perfectly placed bent notes are as integral as Wolf’s growl to the blues power of classics like “Spoonful,” “Smokestack Lightnin’,” “Killing Floor” and “The Red Rooster.”

Blues and rock guitarists who cut and bloodied their teeth on Howlin’ Wolf tunes were heavily influenced by Sumlin: Hendrix often covered “Killing Floor”; the Rolling Stones, Clapton and countless lesser blues-rock lights continue to play “The Red Rooster”; the Doors remade “Back Door Man” in their own image; The Sky Is Crying, a 1991 collection of Stevie Ray Vaughan outtakes, includes the late guitarist’s version of “May I Have a Talk with You”; and Page, Clapton and Beck each flattered Sumlin by imitating him on “Spoonful” and “Smokestack Lightnin.’ ”

Sumlin backed Howlin’ Wolf for 23 years, a stretch broken only by six months in 1956 when he worked for Wolf’s arch rival, Muddy Waters. After Wolf’s death, Sumlin launched his long-delayed solo career, becoming a Chicago blues club fixture and making occasional festival appearances. Over the past 15 years, however, he has picked up steam, touring often and recording numerous albums. Sumlin, now 77, was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2008 and still enjoys performing around the world.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GUITAR WORLD: Did Howlin’ Wolf explicitly tell you what to play?

Not really. When I first got with him, he told me that I wasn’t ready to play his music, so I should go home and think about it for a day, a week, a month or a year, whatever it took. “Come back when you’re ready,” he said. “When you figure out how to play my stuff, then you’re hired.” I went home and prayed and slept with my guitar under my pillow trying to figure something out, because I knew that this man was serious. Wolf did not bullshit.

I had played with a pick for eight or nine years, and I couldn’t put it down. Then I woke up one morning and started playing without a pick, and the first thing I thought of was “Smokestack Lightnin.’ ” I played it better than I ever had and realized, I don’t need no pick. I don’t need anything but my fingers. And that was it.

Everything fell into place when you got rid of the pick.

Exactly. I started playing with a lot more soul. I never used a pick again. That was my secret to unlocking everything. My tone, my sound, everything happened right then. People can’t understand how I play. The average guitar player don’t know what I’m doing. But it’s my thing. It’s what God gave me; I don’t need a pick because I got five fingers. How can one pick compete?

One unusual aspect of your style is that you don’t play a lot of chords.

No, I don’t, but I play a lot of tricks. Like Muddy Waters once said, I’ve got a lot of gimmicks up my sleeves. I know when to get in and when to get out. Lots of guitarists just miss out on that aspect of playing. I know how and where to put it, which is what it’s all about.

Did many of your personal playing trademarks develop as a result of playing with Howlin’ Wolf for so long?

Yes and no. I also played with Muddy Waters for six months and, Lord, I learned a lot from Jimmy Rogers [Waters’ lead guitarist]. I picked up from every guitarist I ever worked with. I’d take a note from here and a note from here, a lick from him and a lick from him, and put it all together. That’s the Hubert Sumlin style. And that’s what I would recommend any guitarist do: listen to players you like and pick things up from everyone and everywhere.

You have to learn how to use your instrument to its fullest. You got five different Es, you got five different As, and you got to use them all. If you’re all over the neck, you’re better. That’s why I never used a clamp [capo] like Muddy or Albert Collins or Jimmy Rogers: Why limit yourself? You’ll notice that kids coming up today play great, and they don’t use a clamp because they’ve got better knowledge of the instrument.

There’s one element of your background that’s almost unique among bluesmen: you studied guitar at the Chicago Conservatory of Music. What was the extent of your formal training?

I studied for six months with this old guy who was with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It was the first time I ever saw a dude who played both opera and blues on his guitar. It had a huge impact on me, because I didn’t know the piano keyboard and I didn’t know how to read—I didn’t know an F from an A, an A from a B or a B from a C. That guy showed me so much in just six months.

Even though you always played electric guitar with Wolf, your sound often had a bit of a country blues vibe. Is that where you come from, musically?

Actually, when I was a kid I wanted to be a jazz player like Charlie Christian more than anything, but I also loved and heard the blues. [Those players] were all around me, and at a certain point, I realized how great all these dudes I listened to were: Charley Patton, Lonnie Johnson, Robert Johnson…all those guys. Peetie Wheatstraw, the “devil’s son-in-law”—Jesus, man, he was something! Then when I got with Wolf and Muddy I realized that they actually played with these guys, and that blew my mind. I’ll never forget my old 78 of Charlie Patton. He was a wizard, man, a genius. I tried to ask Wolf about him, and he said, “Aw, you young punk, you’re too young to understand.” It always hurt me that I missed out on seeing and playing with those old guys, because they wrote the book that Wolf and Muddy electrified and expanded. If Wolf and Muddy were the fathers of rock and roll, then those acoustic guys were the granddaddies.

It sounds like Wolf was very conscious of the age difference between you two.

Yeah. He told me one time, a couple of years before he died, that he was “40 years too early.” He said, “I plowed mules barefoot in December, with snow on the ground, the dirt frozen as a rock.” I said, “Don’t lie, man.” And he said, “I’m not lying. I’m 40 years too early. Things are getting better all the time.” The next year he got sick and went on a kidney dialysis machine.

It can be said that you are the link between the Delta bluesmen and rock and roll. On the one hand, you played with Wolf, who was a contemporary of Robert Johnson and the other guys you mentioned. At the same time, you also exerted a huge influence on the next generation—rock guitarists who weren’t really all that much younger than you.

I’m very proud of that, and I got to meet those guys. I met Eric Clapton in 1970 when I played on Wolf’s London Sessions. I wasn’t supposed to be there, but Clapton said, “If Hubert’s not there, I don’t record.” Then Wolf said he couldn’t record without me, so they had to bring me. Wolf was on a dialysis machine right in the studio, with doctors tending him night and day. He was so sick that on a couple of nights we didn’t even record; we just sat in the studio and got high. Mick Jagger and Bill Wyman came in, and we partied all night long, man. The cleaning lady came in the next morning and everyone was laying there on the floor. Mick Jagger had his head up inside the bass drum. [laughs] It was wild. We had a ball.

Did you spend much time with Clapton?

Yes. One day, Eric sent a limousine for me, and we drove for 30 or 40 miles outside of London to his big old mansion in the country. A gorgeous place, like a castle. We had a beautiful dinner, then he took me down to the basement, where he had all these guitars. It looked like a factory: three and a half walls of a room lined with every kind of guitar you can imagine.

He said, “Pick out a couple of those guitars, Hubert. I’m giving you two of them.” I walked all the way around the room, looking at every one of them. Then I saw this case sitting in the middle of the room. I sat down on the floor and said, “What’s in there?” He said, “It ain’t nothing, man.” I asked if I could take a look. He said. “You don’t want that.” I opened the case and took out this beautiful Fender Stratocaster and started playing it there, sitting on the floor.

He said, “Hey, man, I told you to pick any two you want from those that are up against the wall.” I said, “I know, but this Fender sure sounds good. Is it your regular?” He said, “It sure is.” I said, “I knew it, because that’s the one.” He said, “You mean to say you’re going to take it from me, man?” I said, “No, I can’t do it. I don’t want none of these.” He said, “Take it, man. At least I know it’s got a good home. Just promise me that if I ever want it back you’ll give it to me.”

I kept it for two years and hardly ever played it. Then we were both at the Montreaux Jazz Festival, and I brought it over to him. He asked me how much money I wanted, if there was anything I needed. I said, “Nothing man, it’s your guitar. Don’t embarrass me.” He just gave me a hug. He’s a nice guy. A beautiful guy.

Did you have any sense that you were making history when you recorded those classic tracks with Wolf?

No, and I really didn’t care. But I knew that he was going to be one of the greats. And I was so devoted that I wanted to push him to the top. When you’re recording for people the caliber of Howlin’ Wolf, you’re going to do your best. And in those days, there wasn’t even a question, man: you were going to play your guts out. There had been some days in the past when my stomach ached from not having anything to eat. When I recorded, I would remember those days and remember how I never wanted to go back to them. And I would play!

What kind of personal relationship did you have with Wolf?

We were like father and son, although we had some tremendous fights. He knocked my teeth out, and I knocked his out. None of it mattered; we always got right back together.

You fought with Wolf? He was a huge man.

Oh man, he was big. He could wrap one of his fingers around my guitar neck three times. One time after a gig, we were loading up the truck, and I wasn’t there because I’d run off with this cute girl who’d been sitting on my amplifier, smiling at me all night long. When I got back they were just finishing loading, and Wolf was standing on top of the stage. He started yelling at me, calling me every name you ever heard—and some you couldn’t imagine—because he had to load my gear. I was embarrassed, man, because this was right in front of the whole band.

So I thought, He can’t do this to me. He can’t humiliate me. So I waited until he was looking the other way, and I hit him in the face as hard as I could. He didn’t move. He just turned back real slow and slapped me with the back of his hand. I fell and rolled down the ramp that was pushed up to the stage to load the amps. I got up and walked back, screaming at him. When I got to the top he did the same thing again, and I rolled right back down, spitting out teeth.

Is that why you left to play with Muddy Waters?

No. Me and Wolf patched it up right away. In fact, the next morning, my wife woke me up and said that Wolf had been sitting in his car in front of my house all night long. I went out there and he apologized and gave me money to fix my mouth. I left to play with Muddy because he tripled my salary. They were rivals, and Muddy wanted to take me away from Wolf.

Was the rivalry between Wolf and Muddy apparent to everybody?

Sure. They were jealous of one another; they were enemies: “You stole my shit.” “You did this.” “You did that.” It was endless because they were the two biggest dudes in Chicago, and they were always arguing and competing about who was number one. [laughs] I’ll never forget the day we played the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, and Wolf and Muddy sat down and talked and made friends. They shook hands and said, “No more enemies.” That thrilled me so much, I went and got a beer. This is a business we do every day and love to death, and I never understood that jealousy. It’s music. Who cares who’s the best?

What are your memories of Jimi Hendrix?

He was just a little ol’ dude living in England. It was before his band, the Experience, hit it big. We played in Liverpool, the Beatles’ home, and in walked Jimi Hendrix, a little ol’ hip guy wearing earrings and a bandanna. Wolf said, “What the fuck is this guy? I ain’t saying nothing to that motherfucker.” He came right up to Wolf and asked if he could play his guitar. Wolf nodded and Hendrix picked it up, turned it over and played it with his teeth. [laughs] He played the hell out of it. Wolf looked at him, big-eyed, and said, “You hired, man, you hired!” He said, “No thank you, Mr. Wolf. But I admire you and the blues. You guys are 100 percent. Beautiful, man.”

I never played with him after that, but I saw him do his thing in New York, after he hit, and I fell in love. The guy was great! Just a little ol’ skinny youngster. He was in his twenties, but he looked 16 or 17, and he was good, man. I mean, really good.

Hendrix often called you a big influence. Your playing on several tracks from the Fifties represents some of the earliest instances of guitarist using distortion. How did you do that?

I was just using my Gibson and my Wabash amp, which I used for a long time. It was one of the first amps to have 15-inch speakers. I also got an Echoplex right when they came out, and combined with those 15-inch speakers, that made “distortion.”

What sort of Gibson did you play?

A Les Paul—I believe it was a ’56. I often played them. I also had a Kay guitar. For four years, Wolf didn’t have a piano or even a bass—just two guitars and drums, so Jody Williams [Wolf’s second guitarist] and I coordinated our parts closely and decided that we would both play Kays. I didn’t like that Les Paul all that much, but I sure do wish that I had it now. [laughs]

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.

“I could be blazing on Instagram, and there'll still be comments like, ‘You'll never be Richie’”: The recent Bon Jovi documentary helped guitarist Phil X win over even more of the band's fans – but he still deals with some naysayers

“I just learned them from the records. I don’t read tabs or anything, I don’t read music – I learned by ear”: How a teenage Muireann Bradley put a cover of Blind Blake’s Police Dog Blues on YouTube and became a standard bearer for country blues