Interview: Designer Storm Thorgerson Reflects on Pink Floyd and 30 Years of Landmark Album Art

Visionary designer Storm Thorgerson looks back at 30 years of landmark album art.

“Guitar World?” What kind of magazine is that?” The questioner is Storm Thorgerson. He doesn’t play guitar. In fact, he claims he doesn’t even know “one end of the guitar from another.”

So what’s he doing here? As one of the three partners in Hipgnosis, once the preeminent and most visionary album art design firm in the world, Thorgerson has put his stamp on rock and roll history via photographs, illustrations and ambitious packaging for some of rock’s landmark albums. Works by Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Paul McCartney, Yes, Wishbone Ash, John McLaughlin, Genesis and many others bear the stamp of Thorgerson and Hipgnosis, which disbanded in 1983.

Thorgerson has continued to work as an in demand album designer—two of his most recent clients have been Dream Theater and Phish — and video director. That he remains so highly sought-after is hardly surprising. Any working musician who once sorted seeds from weed in the gatefold of one of his classic creations would probably be thrilled to see Thorgerson have his ethereal way with an album of theirs.

“He’s awesome,” says John Petrucci of Dream Theater, for whom Thorgerson designed the cover of Falling Into Infinity. “We’ve always wanted to work with him. In the past we would actually sketch our album covers ourselves, then get together with the people who would execute them. This time around, Storm insisted on doing the whole thing, and we just deferred. When you’re working with someone of that caliber, you can trust his professional instincts.”

No band has trusted Thorgerson more during the past 30 years than Pink Floyd, whose relationship with the designer dates back nearly five decades to Cambridge, England, where Thorgerson grew up with Floyd’s original band leader Syd Barrett, who was a year behind him in school, and former bassist Roger Waters, who was a year ahead. Thorgerson and Waters played rugby together.

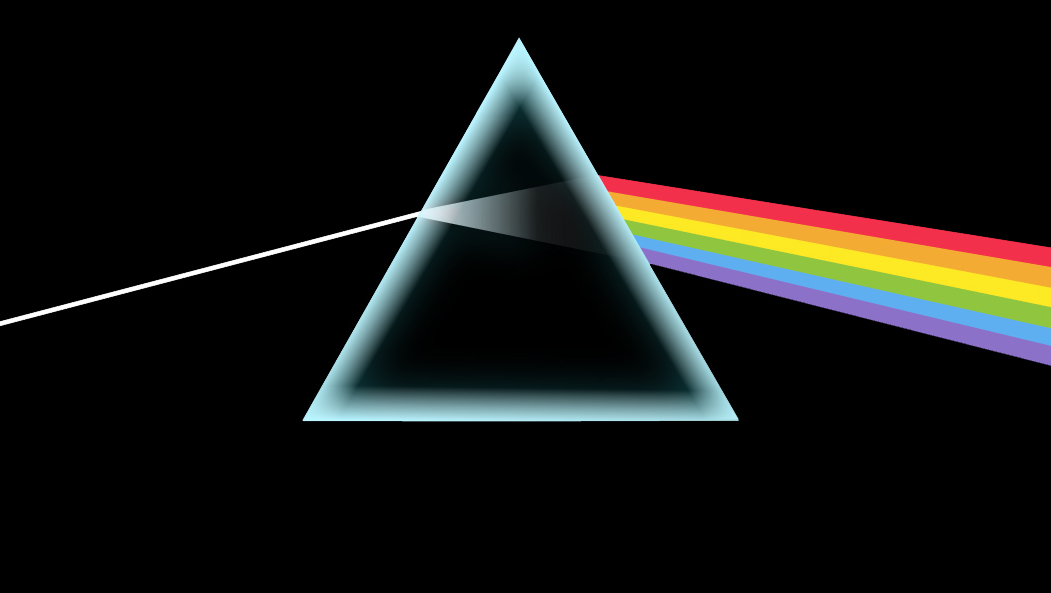

They went their separate ways in college, but everyone wound up in swinging London during the mid Sixties, as rock and roll culture took over the city. Starting with A Saucerful of Secrets in 1968, Thorgerson became Pink Floyd’s chief album designer, crafting a series of indelible images—the picture-within-a-picture cover of Ummagumma, the cow of Atom Heart Mother, the prism of Dark Side of the Moon, the Easter Island–style totems of The Division Bell.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Beyond the albums, there were videos and concert films, as well as covers for solo projects by Gilmour and Barrett. With the notable exceptions of The Wall, The Final Cut and a handful of other releases, Thorgerson was responsible for the visual face of Pink Floyd. He’d blanch at any reference to him as the band’s fifth member, but in Floyd’s extra-musical domain, it was Thorgerson’s vision that set the controls for the heart of the sun.

“He has been my friend, my conscience, my therapist and of course my artistic advisor…,” Gilmour writes in the foreword of Mind Over Matter: The Images of Pink Floyd (Sanctuary Music Library), a 176-page tour of the incredible graphic world Thorgerson has created for the band. “Storm’s ideas are not linked to anyone’s ideas of marketing: that they are atmospherically linked to the music is a bonus. I consider what he does to be art.”

Gilmour also notes with obvious affection that “Storm has always had a big mouth,” an observation confirmed by the designer during a long conversation in his London office, in which he generously shares his thoughts about Floyd, Zeppelin, his myriad other projects and the general state of album art. All this, of course, after he is assured that “the fact that I don’t know anything about guitars doesn’t disqualify me from being in Guitar World, is that right?”

GUITAR WORLD: How did your association with Pink Floyd begin?

THORGERSON It began with Syd, but also with Roger. Roger’s mom and my mum were best friends. Also with Dave, because he used to hang around with us, even though he was younger. It was just a gang in Cambridge… a group of teenagers who came together, not unlike, I should think, they do in many places in America. Roger was more on the fringes of our peer group; we both chased the same girl…but he won that one.

GW What were the Floyd guys like as teens? Ordinary, red-blooded young English lads?

THORGERSON I think that Roger and Syd were not that ordinary…or the others, for that matter. They have ordinary things they do in their lives—they’re not absolutely weird as hell—and they have the usual set of passions. They also make the usual number of mistakes that us normal people do. But they also have drive and talent, obviously. And also, in some cases, great musicianship. I think Dave lent them a sense of musicianship that helped them to be very successful.

GW What was it like, watching the band come together?

THORGERSON I didn’t see it. I went off to another university. They came to architectural school in London, and Dave joined later, anyway. I didn’t do the first album; I didn’t do Piper at the Gates of Dawn. I knew them, and I knew they were being nearly successful. But although I knew them as friends, I didn’t have a particular view of this, other than it was exciting to know a band that might be successful. I didn’t pay too much attention; I was too preoccupied with myself, as one is when one is younger. When I met them again, they were in the process of losing Syd. So their main creative talent was sort of going off the rails. It’s hard to find the correct way to describe it, really.

GW In Nicholas Schaffner’s book A Saucerful of Secrets, he describes a meeting in your apartment where Syd’s ouster from the band was discussed. What was that like?

THORGERSON It’s a bit long ago to remember. [laughs] Because they knew that I knew Syd, and I knew them, they thought maybe I could perhaps offer some limited advice as to what to do. Rog, who hadn’t spoken to me in quite a bit, I think was interested in talking to me about what I thought was going wrong with Syd, ’cause he knew that I’d been relatively close to him in Cambridge. But I don’t think that I had much of an idea about what they should do, really. It’s very difficult, even when you’re an adult, to know what to do when a friend goes off the rails. It was very hard for the band; I don’t think there was ever a desire to get rid of him, but they had to function.

We talked about it, as chaps do. I couldn’t proffer much direct advice, but we chatted about how horribly difficult it was, what the hell they were going to do. Syd was in such a state at times, you just couldn’t talk to him. I think I was of the opinion then that it made sense to get rid of him if he really was preventing the band from functioning. He seemed to show clear signs of getting worse rather than better, and also seemed to be unreachable. If a person seems unreachable, or appears to be immune to entreaty, then you have to reluctantly decide to go on without him.

I think it’s very sad, really. And they were very sad about it. I think “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” is the most concretized form of their sadness, if you like. I think that song, written eight years later, approximately, is a clear indication that this was something they did not want to happen.

GW So in the midst of this, you wound up doing the art for A Saucerful of Secrets.

strong>THORGERSON I think they knew they didn’t want the record company to handle it. This was in the days when the Floyd and the Stones and the Beatles were beginning to take power back to themselves, especially artistic power, away from the record companies—to literally take more control of their artistic output. I think they realized that, along with the music, sleeves are things that last, and that maybe they’re important in their own way. Even if they’re not as important as the music, except to people like me.

I think they wanted someone they trusted and who knew them to do it rather than some impersonal or third party designer that had no relationship with them. Their music was intimately related; why shouldn’t their cover be related?

GW What kind of working relationship did you fall into with the band?

THORGERSON You get used to each other and you chat and you develop some shorthands. And you prick your ears to pick up the bits that are most interesting. Dark Side, for example, came from sort of an aside said by Rick—not necessarily the most likely source. The back of Ummagumma comes from something Nick Mason did. Meddle comes from God knows what. Wish You Were Here comes from conversations with Rog in particular. Animals is actually a Roger thing; although we did the work, it was his idea. A Momentary Lapse of Reason comes from a line of lyric of Dave’s. The Division Bell comes from several things.

What happens is, in all these cases, you still have a sort of communication with the band. That comes and goes. It breaks down sometimes. It’s mostly by talking, by being there—by going to gigs, particularly, so that you get some sensation of what the music is really like, ’cause you don’t find that much during recording, since a lot of it is done in bits.

GW Is it important to start working on the album art at the gestation of the project?

THORGERSON It depends on what the gestation was. I didn’t have anything, really, to do with the start of Atom Heart Mother, and when I asked them what it was about, they said they didn’t know themselves. It’s a conglomeration of pieces that weren’t related, or didn’t seem to be at the time. The picture isn’t related either; in fact, it was an attempt to do a picture that was unrelated, consciously unrelated.

GW It’s a cow!

THORGERSON ’Cause that seemed to be the most unrelated thing it could be. Also, I think the cow represents, in terms of the Pink Floyd, part of their humor, which I think is often underestimated or just unwritten about. Not that their music is funny, but I think they have good senses of humor. Nick is very droll; he’s got a very good dry sense of humor. And Roger is very sharp. Dave has his own particular sense of humor, as well. I think that’s why they chose the cow. I think they thought it was funny.

GW Any rejections of your work that come readily to mind?

THORGERSON Yeah, for Animals in particular. There were two roughs for Animals, one of which was a picture of a young child, age three or four, with a teddy bear, opening the room to his parents, who are on the bed making love, being caught in the act, and appearing to be animals. I thought that was really good, but they didn’t like it.

For the same job, I also suggested this idea about ducks. In England, the essence of bad taste is to put plaster ducks on the wall. So I took that idea and put real ducks and nailed them to the wall to suggest that people are really animal in some of their artistic and moral decisions. I think they rejected that not because they didn’t like it—because I think they did—but because it was very heavy. These were ducks I bought at a poultry place and nailed to a wall.

So yeah, it happens. For Dark Side of the Moon, we did six or seven complex roughs of all sorts of different things that were eminently suitable. And we were very excited and looking forward to showing these different ideas to the band. At the actual meeting, we gathered around and…it took about a minute! They looked at all these things and looked at the prism and said, “We’ll have that.” We said, “Oh, there’s this and this, have a look at this.” And they said, “No, we’ll have that. Now we’ve got to go back and do our real job.” And they walked out of the room to continue recording.

GW You tell a great story in the book about shooting the pyramids in the middle of the night for the Dark Side poster.

THORGERSON I scared myself shitless doing it, too! I hired a taxi at 2 o’clock a.m. to take me out to the pyramids. So there I am, thinking I’ll be fine, and I put the camera on the tripod to do a long-time exposure. It’s a wonderful, clear night, and the moon is fantastic. So I’m doing it…and then, at like 4 o’clock a.m., these figures come walking across—soldiers, with guns. I thought, This is it. The game is up—young photographer dies a strange death in a foreign land. I was actually really scared. Of course, all my fears were unfounded. They were very friendly. They wanted a bit of bakshish, a little bit of money to go away. They kindly pointed out that where I stood was actually a firing range, and that they’d come to tell me it wasn’t very cool for me to be there. If I was there first thing in the morning, I might get a bullet up my butt.

GW It’s obvious from the book that you’re very fond of Wish You Were Here. Did you feel you had to one-up Dark Side?

THORGERSON Not really. Dark Side… I think it’s sort of goodish, good. Sort of. But I don’t think it’s a moving piece; I don’t think it’s as moving as I would like in terms of their music. So when Wish You Were Here came around, I was quite fueled up for it. In fact, I was even more fueled up for it. And I only suggested one thing to them, as opposed to several to choose from. It was quite nervy, ’cause normally for the Floyd and other bands I would suggest a few different roughs to choose from. But the one thing that was suggested to the band was what they used.

GW Those images were mostly inspired by “Shine on You Crazy Diamond,” correct?

THORGERSON It was particularly to do with “Shine on You Crazy Diamond,” yes. In a way, that theme could be expressed by one word: absence. It was absence in terms of relationships, absence in terms of previous members of the band. Also, absence in terms of a commitment to a cause or a project. This was a feeling that I think was in the air.

GW How involved did you get in those inner-band Floyd politics that started to surface during the mid Seventies?

THORGERSON The divorce, you mean? Quite a lot on Dave’s side. Roger has not spoken to me since 1980. I was not privy to meetings they had. I just know that there was a very, very hard time indeed, with a lot of fighting.

GW Did you have a falling out with Roger?

THORGERSON I don’t know whether it was a falling out. He didn’t want to use me on The Wall, which is understandable. He was also supposedly cross with me for something, for a credit I’d given him in a book I’d done called Walk Away, Renee. An illustration of the Animals cover appeared in the book, and Roger didn’t like the credit I’d given him. I corrected it on a reprint, so I don’t know whether that was really what upset him.

GW How do you feel about doing album art in the CD age?

THORGERSON This is a continuing debate. The usual response of graphic designers is that the CD provides you with less of a graphic canvas to work on. But it has its own challenges. Also, designers are, to a great extent, realists; you’ve got to function, you’ve got to work. CDs are here. You’ve got to learn to like them. Obviously, though, I would rather have a bigger canvas. That’s probably why I build big things sometimes. For Phish, I built this ball of yarn that is the size of a small house.

GW Part of the challenge seems to be in packaging, too, rather than simply designing a cover or a booklet.

THORGERSON I think designers are driven to do that because there’s less of a canvas to work on with just the booklet. So where are they going to get their rocks off? Because it’s smaller, it becomes more touchy, more of a tactile thing so that you can play more with textures and boxes and fold-outs and Digipaks—this pack, that pack, see-through trays, embossing, etc., etc. I have obviously indulged myself; I enjoyed greatly doing Pulse for the Floyd.

GW A spectacular CD package. How did that come about?

THORGERSON I think it came about for two particular reasons, one of which was that it was a live album. I wanted the package to be live, so we came up with a list of things that included balls and mazes. We had some that made a noise when you opened it, squeaked at you, some that smelled, others that you could see in the dark. And this one that had a flashing light thing, which reflected the heartbeat in Dark Side. And also it was a light, which is really handy ’cause obviously the Floyd have a really good light show. The other thing was that I was also fed up with having to squint at spine details. I thought, I’m going to make something that I know where it is when I want it. It was about a spine that was completely and utterly unique and recognizable, that says: “Here I am. You want to play me? I’m over here.” I think it works really well. Mine still blinks.

GW I take it from your continued involvement with the Floyd that you view the current incarnation of the band as legitimate.

THORGERSON Yes, because Roger resigned. If you leave a band, I cannot see the moral imperative that would allow you to presume it finished. If you leave, you leave. And presumably a man of Roger’s standing and intelligence left because that’s what he wanted. I think it’s peculiar because if it’s not what he wanted, why did he do it? Nobody asked him to. Nobody pressured him to. So I presume he wanted to. But there was a lot of fighting afterward, so you have to presume that something went astray.

GW You chose the cover of The Division Bell to be the cover of your book. What’s the special significance this piece has for you?

THORGERSON Obviously, we were tempted to choose Dark Side because of its success, but we eschewed that choice in favor of art. I hope it doesn’t sound over-pretentious to say that. On a more simple level, this is the picture I have liked the most. It is the image I’m proudest of—at the moment. I think it says a lot about the Floyd. I think it says a lot about past Floyd. I think it says a lot about Roger. I think it says something about the layers of meaning, the elegance…the ghost, the spirit of Floyd. It says something about their ambiguities. It says all those things. It most particularly says something about departed friends.

GW And from your vantage point, do you think there is any truth to the rumors that Roger and the rest of the Floyd will be playing together again in the coming year?

THORGERSON [laughs] I’ve heard that. It sounds like bull to me. Although I think it would be quite interesting and dynamic if it did occur. I think you’re talking about two huge talents here. And as much as there may have been friction, there’s mileage to be made out of friction. But if you ask me if I think it’s a reality—I don’t think it’s a reality. But then, of course, what’s real and what’s not with the Floyd?