Guide to The Beatles' White Album: the Recording Equipment, the Songs, the Conflicts

Having opened a Pandora's box with their critically acclaimed and commercially successful album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Beatles faced serious competition from a variety of open-minded artists who were expanding rock music's barriers.

Newcomers like Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, Pink Floyd and the Doors, and even contemporaries like the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys and Bob Dylan were challenging the Beatles' role as innovators. But rather than continue to pursue the psychedelic excesses of the previous year, the Beatles went in the opposite direction.

The result was a double-album that found the group returning to a more stripped-down rock and roll sound and often eschewing electric guitars for acoustics. Popularly known as the White Album for its stark white sleeve, The Beatles was made during a particularly tumultuous period for the band.

In the wake of manager Brian Epstein's death in August 1967, Paul McCartney had begun to assume more of a leadership role, creating an imbalance in the group's seemingly democratic power structure. At the same time, John Lennon, newly in love with Yoko Ono, was beginning to lose interest in the Beatles.

George Harrison had grown tired of having his creativity quashed by Lennon and McCartney and began pushing back against their authority. Starr, meanwhile, was becoming fed up with sitting around in the studio and waiting for the others to finish writing their songs. Ironically, the group's disintegration occurred after a fruitful period of togetherness, when the four Beatles traveled to India in spring 1968 to study transcendental meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

While in India they wrote more than 30 songs, many of which became the basis for the White Album, including "Dear Prudence," "Julia" and "Mother Nature's Son." Upon returning to England, the group convened at Kinfauns, George Harrison's house in Esher, to record four-track demos for the new album. By some accounts, neither Lennon nor McCartney was willing to sacrifice some of his songs to make room for others, and thus The Beatles became a double album.

According to Harrison, "The rot had already set in."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But it's also true that the Beatles' creative energy could no longer be confined to a single album—nor a single studio. As a result, when it came time to record the album, the Beatles essentially took over Abbey Road, occupying several studios at once while they recorded their new songs, often working on them individually rather than as a group.

Anyone who walked down the halls of the facility on a June evening in 1968 probably would have been shocked by the contrast between McCartney recording the wistful "Blackbird" on an acoustic guitar in Studio Two while Lennon was in Studio Three manipulating and mutilating tape loops for "Revolution 9," his and Ono's musique concrete tape experiment.

After McCartney's dominant role on Sgt. Pepper's, Lennon was eager to assert more control on the White Album. His song "Revolution 1" was the very first tune the group tackled for the record when the sessions began on May 30.

Though Lennon insisted the Beatles release the track as their next single—the first release on their new Apple label—McCartney convinced him that the tempo was too slow and unlikely to make the song a Number One hit. Lennon relented, but on July 10, he led the group through a faster, rocking version of the tune, called simply "Revolution," which was ultimately selected as the flipside for "Hey Jude," the Beatles' debut Apple single.

As on Revolver and Sgt. Pepper's, engineer Geoff Emerick was responsible for the song's innovative sound, most notably the heavily fuzzed-out guitar tones. To create them, Emerick plugged Lennon and Harrison's guitars (probably their Epiphone Casino and Gibson SG, respectively) directly into Studio Two's mixing console, overdriving two REDD.4 7 mic preamps to create the warm distorted tones.

"I had an idea that I wanted to try," Emerick recalled of the session in his 2006 memoir, Here, There and Everywhere, "one that I thought might satisfy John, even though it was equipment abuse of the most severe kind. Because no amount of mic preamp overload had been good enough for him, I decided to try to overload two of them patched together, one into the other. As I knelt down beside the console, turning knobs that I was expressly forbidden from touching because they could literally cause the console to overheat and blow up, I couldn't help but think, If I was the studio manager and saw this going on, I'd fire myself."

Emerick didn't have to worry about being fired—on July 16, just six days after the "Revolution" session, he quit. The day before, he'd worked on a particularly grueling vocal session for the McCartney track "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da," and the tension had simply become too much for him. "I was on the verge of a breakdown during the making of the White Album," Emerick says. "It was because of the emotional stress for me. I was just not into it."

The conflicts only became worse as the work continued through the summer and into autumn. Ringo Starr was next to leave. Feeling unappreciated by his bandmates, he quit the band in the middle of recording "Back in the U.S.S.R." on August 22. In his absence, McCartney (and possibly Lennon and Harrison as well) handled drum duties on the song, as he did when the threesome recorded "Dear Prudence" on August 28. (As these are the first two songs on The Beatles, Starr isn't heard on the album until "Glass Onion.")

Starr returned on September 5, but his brief exit demonstrates how strained The Beatles' relations were becoming. Even though the band members spent a considerable amount of time working separately on the album, they recorded most of the backing tracks for its 30 songs live as a group. Typically, the writer of each song would then work on overdubs alone or with another Beatie or two assisting.

As several tracks were being worked on at once, George Martin was unable to oversee all of the sessions. In his absence, the individual band members or Martin's assistant Chris Thomas took over. Harrison in particular seemed more empowered than he had been on previous albums. In addition to often working on his own songs in a separate studio, he made decisions without consulting anyone else, such as when he brought in Eric Clapton to play lead guitar on "While My Guitar Gently Weeps."

Harrison recalled that Clapton's presence made his bandmates "try a bit harder; they were all on their best behavior." Harrison was also becoming less inclined to defer to Martin's authority. Once while Harrison was working on the mix for his song "Savoy Truffle," Martin said he thought it sounded too shrill and trebly. "I like it like that," Harrison said, turning his back on Martin and continuing his work.

But amid the enmity, the Beatles were, as always, breaking new ground in the studio. By 1968, they had recorded in each of Abbey Road's three studios, but for the taping of "Yer Blues" on August 13, they found a spot that they had not used yet—a small utility closet known as the Studio Two "annexe." The tight quarters gave the recording an especially "live" sound, thanks to microphone leakage and sound-wave reflections off the walls.

From a technological standpoint, the White Album is significant for marking the Beatles' transition to eight-track recording. In this respect, Ken Scott, who replaced Emerick in the engineer's seat, played an instrumental role. Abbey Road had purchased several 3M eight-track recorders in May 1968, but the machines required numerous modifications before George Martin would approve their use on Beatles sessions. However, during an evening of work on ''While My Guitar Gently Weeps," Scott removed one of the unmodified eight-track machines from storage when he could no longer tolerate being limited to four tracks.

Although only 10 of the album's songs were recorded entirely on eight-track machines, by the time the album was finished, the Beatles' four-track era reached its end. Despite having more tracks at their disposal, the Beatles kept the album's music surprisingly straightforward and stripped down.

They made up for the recordings' simplicity by offering listeners an impressively eclectic 90-minute musical journey that included acoustic folk, rock and roll, blues, country, acid rock, music-hall schmaltz, avant-garde experimentalism and smartly crafted electric pop rock. Few artists cover as much stylistic ground in their careers—the Beatles pulled off this monumental feat in a mere four and a half months.

In the end, even the double-album format was not enough to contain all of their creative ambitions, and several of the songs they wrote during this period were put aside for later release. Some, like Harrison's "Not Guilty" and Lennon's "What's the New Mary Jane," were recorded during the White Album sessions but not issued.

And while George Martin has always believed that the group should have trimmed the collection down to a single disk, even the most casual Beatles fan would have trouble picking five songs to cut from the White Album, let alone 15.

THE BEATLES: EXTRA FACTS

Recorded: May 30 to October 13

Location: Abbey Road One, Two and Three; Trident Studios

Released: November 2, 1968

TRACKLISTING

- Back In the U.S.S.R

- Dear Prudence

- Glass Onion

- Ob-La-Dt, Ob-La-Da

- Wild Honey Pie

- The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill

- While My Guitar Gently Weeps

- Happiness Is a Warm Gun

- Martha My Dear

- I'm So Tired

- Blackbird

- Piggies

- Rocky Raccoon

- Don't Pass Me By

- Why Don't We Do It in the Road?

- I Will

- Julia

- Birthday

- Yer Blues

- Mother Nature's Son

- Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey

- Sexy Sadie

- Helter Skelter

- Long, Long, Long

- Revolution 1

- Honey Pie

- Savoy Truffle

- Cry Baby Cry

- Revolution 9

- Good Night

RELATED SINGLES

• "Hey Jude" / "Revolution," August 30,1968 (Apple)

THE 3M M23

Abbey Road's first eight-track, the M23 was rejected by George Martin for various technical issues. The tape deck remained out of use for months while the studio's technicians modified it to his specifications. Fed up with recording on four-track, The Beatles "liberated" the M23 on September 3, 1968, and used it to record 10 tracks on the White Album.

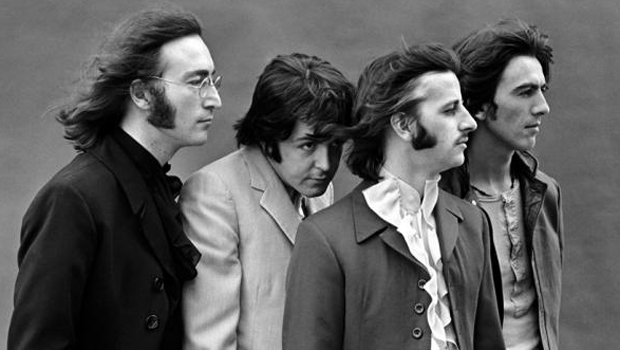

Photo: The Beatles, 1968—thebeatles.com

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)