“I said to Paul Hamer, ‘The best I can do is just play your guitar.’ I didn't want any money for it, because when I like a guitar, I just like it”: On Gary Moore's full-length tribute to Phil Lynott, Greeny took a backseat to Superstrats

On his own after a number of short-lived bands and the death of his friend, Thin Lizzy leader Phil Lynott, the late guitar hero ditched the ‘hard rock’ sound he'd grown tired of for something with more modern ingredients

This interview originally appeared in the September 1987 issue of Guitar World.

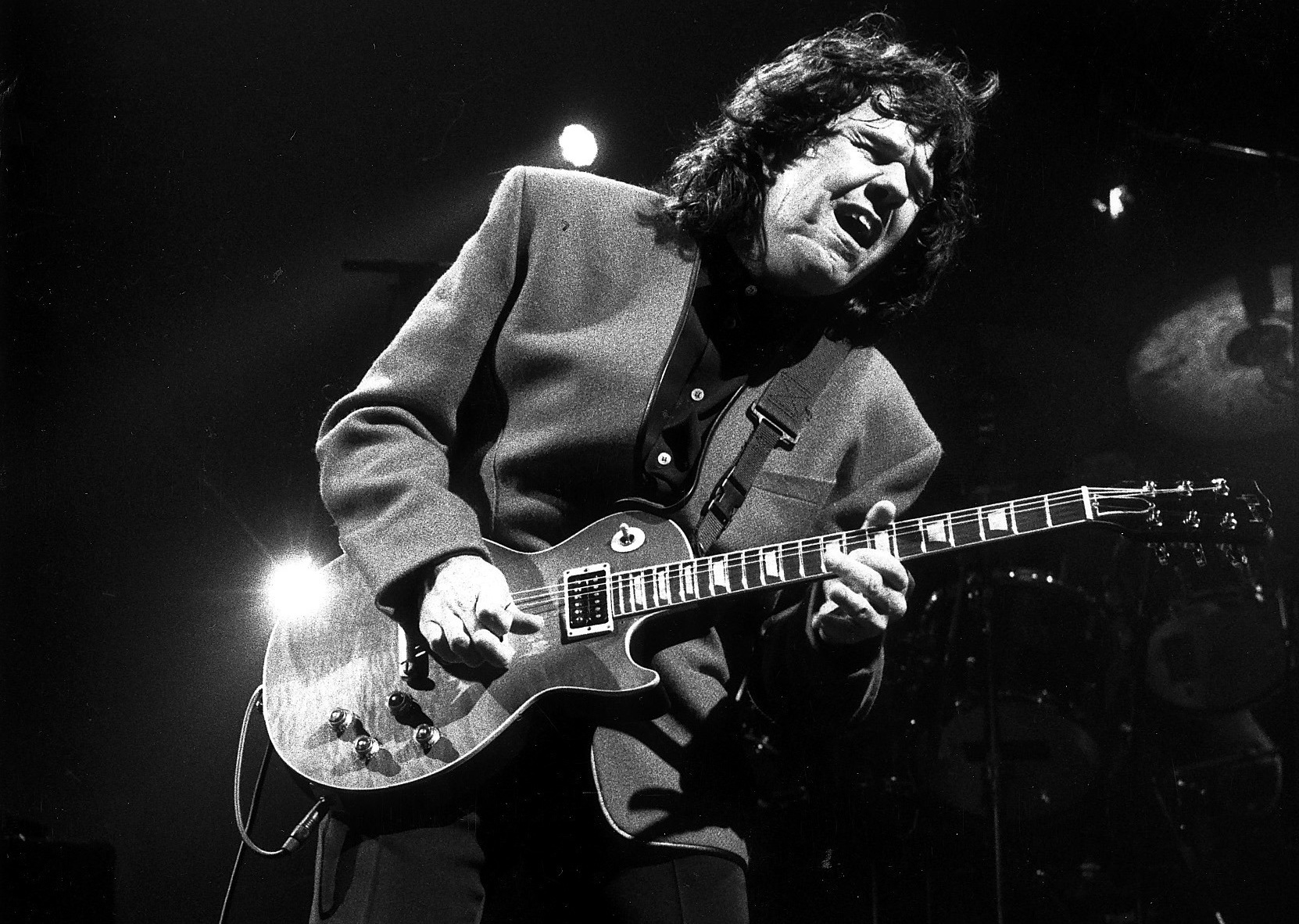

Gary Moore is busy storming the stages of Europe as we put this issue to bed, yet his technically experimental and rousingly adventurous new album, Wild Frontier, is beginning to crash upon American airwaves like a gathering typhoon.

Dedicated to former Thin Lizzy bandmate, Phil Lynott, the album contains not only Moore's trademark slashing axwork, but some very thoughtful tunesmithing and singing, as well. It marks the maturation of this wild Irish rose into a complete rock entertainer, one who has paid his dues.

After 18 years of hard work, innumerable roles in different bands, many successes, and some setbacks, the Irish guitarist is at the high point of his windswept career.

Moore is a dyed-in-the-wool, full-blooded guitarist with a highly developed, personal style. With his inimitable flair for melody, he has grown into a true guitar hero.

“In Belfast, where I grew up,” he says, “I came in touch with music at an early age. My father was a show band promoter, who took me along as a little nipper of five and put me up on the stage with the musicians to sing.”

After a false start on the piano – “I found reading musical notation frightfully boring” – his career was first launched at the age of 11, when his father gave him a guitar and a guitarist in the band showed him some chords.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He began teaching himself, laboriously copying licks from Hank Marvin of the Shadows. Then came the now-classic influences of musicians like Jeff Beck, Peter Green, Clapton, and Hendrix.

Moore learned quickly, and joined his first professional band as soon as he finished high school. He was 16 when Skid Row started up. The R&B-style band from Dublin had a singer named Phil Lynott, and it was then that the cornerstone of a long, fast friendship was laid. Moore's Skid Row period lasted three and a half years.

“We made two LP's, Skid Row [1970] and 34 Hours [1971]. We made a third, but it was never released.”

Before Moore got the first Gary Moore Band on its feet, he made a guest appearance with a certain Dr. Strangely Strange, where he played Irish folk tunes.

Though the Gary Moore Band's first LP, Grinding Stone, was a flop, he soon, in 1974, found himself in Thin Lizzy for a six-month stint, replacing Eric Bell.

The next stop was a band called Colosseum II, until, in 1977, Thin Lizzy beckoned again.

“The boys wanted to start a US tour, when a few days before take-off Brian Robertson hurt his left hand in a brawl. Again, I leaped into the breach and went on tour with them.”

Then came another short term with Colloseum II, before his third and final phase with Thin Lizzy one year later. Although they were tight as friends, Lynott and Moore had different sets of ideas, musically, and soon went their separate ways once again.

Moore went solo again with Back On The Streets, which featured a rhythm section of Simon Phillips (drums) and Lynott (bass and vocals) as well as Colloseum II players Don Airey and John Mole.

The band GForce followed, then a lengthy stay in the US, which produced collaborations with Cozy Powell, a solo project with Jimmy Bain, Tommy Aldridge, and Charlie Hahn, and some work with the Greg Lake Band.

These were all more or less failures for the young Irishman, as he sees them now: “Unfortunately, the things didn't work out the way I would have liked them to.”

1983 put an end to the chaos, and laid a foundation for continuity, though the cast of characters continued to change.

The Gary Moore Band started up again with Ian Paice (drums), Neil Murray (bass), and Tommy Eyre (keyboards). After a short while, singer John Sloaman joined; after which came two albums, Corridors Of Power and Victims Of The Future. The latter featured ex-UFO man Neil Carter on keyboards, bass, and vocals.

Moore and his band played everywhere – from the smallest gigs in London to never-ending tours of huge European arenas. The live double album We Want Moore is the document of this phase, with the ballad Empty Rooms becoming a surprise hit.

With the LP Run For Cover, Moore, with the influence of Neil Carter, became more open to stylistic variations, and began to leave his typical style behind. This brings us to the current tour and the new album, Wild Frontier, which is a watershed, indeed.

The obvious Irish influences behind Wild Frontier and the tribute to Phil Lynott (Johnny Boy) illustrate how Moore has switched over to combine the most modern studio techniques with what for him is an unusual way of producing.

The basic tracks were not, as earlier, laid down with the goal of getting a good drum track first and then building up the song. Because of drummer problems – Ian Paice went back to Deep Purple and Gary Ferguson left the band – Moore was forced to remember that there is such a thing as a drum machine.

After he put down a few demos with digital drums, the greater part of the drum tracks were set down in the Marcus Studio in London with a Linn 9000. As soon as most of the tracks were finished, Roland Carridge came and did some overdubs.

This kind of work is completely normal these days, because the final drum parts and fills can be altered to fit the arrangements, which, during a Gary Moore production, are constantly changing. Billy Idol and Steve Stevens use the same method.

A change is also clearly perceptible in Moore's guitar playing. Until about two-and-a-half years ago, he never took to the stage without his red Stratocaster and his beautiful old Les Paul Standard.

“The Strat is from 1960. It belonged to Tommy Steele, a well-known rock 'n' roll singer in England in the Sixties. It's still in mint condition, exactly as Hank Marvin once played it. The Les Paul Standard, I bought it one day from Fleetwood Mac founder Peter Green. It's the same guitar Peter used when he wrote Albatross, Oh Well, and all those other songs.” [ed. Now in the possession of Metallica's Kirk Hammett, this Les Paul, now known as “Greeny,” is one of the most storied guitars of all time]

In the meantime, Moore has become more and more interested in new guitars, although he started off the G-Force project playing a Charvel. Since he found a reliable guitar tech in Keith Page, the Floyd Rose system has become a stronger component of his show.

“I always used the old Fender for a particular sound. As I brought my equipment up to date, I thought I should give the Floyd Rose system another chance. When I first tried it out, it didn't have a very fine sound, and I didn't think you could do much with it live. Now I see the whole thing differently, and I must say I've gotten used to it.

“The voice-ability is enormous, and I prefer the Floyd Rose System in every case to the Kahler system, because the sustain on the Kahler system is definitely worse. You just have to play the guitars dry to hear the difference.

I said to Paul Hamer, ‘The best I can do is just play your guitar.’ I didn't want any money for it, because when I like a guitar, I just like it

“The Floyd Rose sound is much more natural. It's my opinion that the sound of a Chrome-plated Floyd Rose system is far and away better than, for example, a black system. The sound is fuller, with more sustain. An obvious difference.”

Moore mainly uses two Charvels, equipped with EMG humbuckers and Floyd Rose tremolos. Nonetheless, they are not officially his main guitars, for the guitarist also recently discovered a love for Hamer instruments.

“I use the Hamer guitars to the same extent, simply because I find them really good. A few years after I discovered the Charvels, it was a great experience getting acquainted with Hamer guitars. I wrote the album Run For Cover with these guitars, for example. They're based on the same principle as the old Les Paul Junior.

“I don't have any advertising deal with Hamer. I visited the factory in Chicago, and I said to Paul Hamer, ‘The best I can do is just play your guitar.’ I didn't want any money for it, because when I like a guitar, I just like it.”

The diverse instruments that Moore has collected over the years include a 12-string acoustic Takamine, of which only two exist (The second is owned by Greg Lake), and above all some Paul Reed Smith guitars. Of these noble items he calls three his own.

Moore's earlier equipment always depended on where he was playing and consisted of different Marshalls from 50 to 300 watts, with a 4 x 12 box, plus chorus, echo, and distortion, but thanks to Keith Page, a permanent set-up was built.

The centerpiece is Moore's older 100-watt Marshall top from 1971, which certainly hasn't been modified, but nonetheless through countless additions and repairs over time has acquired its own special sound. Behind that are two other 100-watt tops, one of which, like the older top, is connected to a 4 x 12 box.

At some point the label ‘hard-rocker’ began to get on my nerves, and I decided to break those chains

The third top controls two of these loudspeaker boxes, to provide the requisite fullness for a live sound. Before the guitar signal reaches the amps, it runs through an Ibanez Tube Screamer, a Roland Space Echo connected to a volume pedal, then into a Roland SDE 3000 Digital Delay, and from there into a Roland Dimension D, where the signal is split into the two stereo channels.

In the studio, however, Moore installs a completely different arrangement, with Dean Markley amps, Gallien-Krueger, and other brands.

“On the stage I prefer the Marshalls, simply because the places we play are very big and only the Marshalls pack the power that I must have. This power is very important for me on live gigs, so that everything goes off all right.”

The black roll-neck sweater and leather jacket emphasize his pale complexion. A few days of hard promoting have mercilessly left their traces in Gary Moore's eyes. And while the dark-haired Irishman discusses his latest work in the lobby of one of Munich's luxury hotels, in a pleasant voice which sounds much milder than on his records, his tomato soup is getting cold.

Your new album, Wild Frontier, doesn't sound as harsh as your earlier music.

“You're right. At some point the label ‘hard-rocker’ began to get on my nerves, and I decided to break those chains. My music definitely doesn't sound like AC/DC or the Scorpions – nothing against either of these bands, they're okay. But I was fed up with that image. I wanted to get away from the so-called American sound.”

In songs like the ballad Johnny Boy you even play up the Irish influence.

“I really wanted to get back to my musical roots. The impulse for this change was a trip to Ireland last year. There a lot of famous musicians appeared for the benefit of the unemployed in Ireland. And it was suddenly clear to me how much talent cities like Dublin and Belfast have produced: people like Van Morrison, Rory Gallagher, the Chieftains, Bob Geldof, and U2. I wanted to remember the music I grew up with.”

I had this dream of an ideal singer who would one day fall right out of heaven and into my band. Since it didn't happen, I have to write the songs for myself – like it or not, a little deeper

Being so patriotic, you must really be proud of Bob Geldof, who nearly won a Nobel Prize.

“Naturally, it's very satisfying that the person who got the ball rolling for Live Aid comes from Ireland, but I was never a real fan of Bob's music – only the earlier stuff. In spite of that, I'm very sorry that he's having so much trouble selling records now. People only want to see or hear of him in connection with some charity performance or the other.”

Have you been listening to a lot of Irish folk music lately?

“I usually don't go into record stores to buy folk music. But the tunes from my childhood are still buzzing around in my head. So it's not difficult for me to write songs that resemble the traditional Irish melodies, especially when they sound a little different on the guitar.”

Your lyrics also revolve around the theme of Ireland ...

“Wild Frontier, for example, is a pretty political song. It describes the fate of anybody who grew up in Belfast and then returns after many years. It's shocking how much the city has changed.”

But not all your lyrics have this personal background, or do they?

“Yeah, most of them do. Unfortunately, I find it very difficult to concentrate on reading books, and I rarely read one to the end. At best I get my inspiration from the newspapers or from television.

“The song Stranger In The Darkness tells of young people who visit the promised city of London and are seduced into heroin addiction. They even turn to prostitution to support their expensive habit. An anti-heroin song with a typical Soho scenario.”

And another song, which, like Johnny Boy, is dedicated to Phil Lynott?

“Sure, to a certain extent. Mainly I see the whole album as a tribute to Phil. That's also part of the Irish influence. The music that we played with Thin Lizzy also had a Celtic influence, especially the [1979] Black Rose album. Obviously, Wild Frontier isn't a concept album. I dedicated the album to Phil simply because it's the first one I've produced since he died. I can really imagine Phil singing Wild Frontier.”

Why does your voice sound deeper on this album than it has in the past?

“I used to write my songs in a higher voice, because I had this dream of an ideal singer who would one day fall right out of heaven and into my band. Since it didn't happen, I have to write the songs for myself – like it or not, a little deeper. I certainly had success in the studio with the old sound, but not on stage when I had to play guitar, too.”

Lately your guitar isn't sounding as strong and bold as it used to.

“Oh yes, the guitar is still strong and serious, like in the instrumental The Loner on the Wild Frontier album. The guitar part hasn't disappeared. But you are right to the extent that my songs are no longer tailored for the guitar. They are songs in themselves.

“When I stopped being not only the guitar player in my band, but the lead singer as well, I had to divide my songwriting efforts between the two parts. The new record is more complete – with ‘Gary Moore as composer, co-producer, singer, and guitarist.’ On the stage the guitar still has a big part.”

Your keyboard player, Andy Richards, used to work with people like Frankie Goes To Hollywood and Nik Kershaw. How come you gave Andy so much influence on this record?

“Andy wrote a great keyboard part for Run For Cover. In between he also worked as producer with people like the Belle Stars and Malcolm McLaren. But he is also a very gifted musician. Also, he owns a Fairlight 3, and that was naturally very important for a couple of tracks on the new album.

“The song The Loner was a struggle between the guitar and the keyboards. The drums are Fairlight and so is the bass, and then there is also guitar and violins laid over. This combination of natural instruments, that stir up the emotions, and cold-sounding technology fascinates me. When the Chieftains mix their ethnic-Irish instrumental parts with sequencers, that's extremely interesting to me.”

So your band is going to stay for the most part the same, concerning drums?

“Yes. In the beginning we were working with drummer Gary Ferguson. But he had to take off, because we decided to use drum machines instead.”

Why do you hold such a high opinion of drum machines?

“I wrote these songs with the help of computers. At home I have an eight-track and a simple drum machine, and the rhythms I produced with these were the basis for all my songs.

“When we were in the studio with a real drummer we wanted to change, it didn't sound perfect enough. I kept hearing these small mistakes, minimal to be sure, but I couldn't endure it, and I sent the drummer home. He really felt somewhat shit upon.”

Did you write the new songs in a rush?

“No. I took about six months for that. I started more than a year ago with the title song. But we didn't start recording until the beginning of last summer. In between we played the Open Air Festival with Queen. We were also in Germany. So we had to split the recording into three sections – one part before the festival, one part after, and then at Christmastime we had to go into the studio again, to complete the album.”

How do you manage with such a divided schedule?

“I manage quite well. I don't like to spend a lot of time in the studio. The enthusiasm winds down, and I get bored. And I've been told that my enthusiasm dies because I do so much of the work myself. That's something else, when you go into the studio with an entire band. Alone, you burn out very quickly.

“I like to divide up the work, maybe a Monday in the studio here, then some time off to write some new material, and then another Monday back in the studio.”

What do you do in between, to turn it off?

“Give interviews [satisfied laugh]. No really, I always have my music in my head. I develop the ideas slowly, until the song crystallizes.

“The best ideas come in the mornings. When I can't get any farther on a piece after a day's work, I go to bed. And when I get up the next morning I get a brainstorm, and run to the studio to write it down. It always fascinates me the way some songs just write themselves, with none of my doing. They come out of nowhere.”

Where are you living now?

“About 60 kilometers from London, way out in the country. I try to keep my private life and my music business separate. When the two realms mix too much, sometimes it goes downhill.

“I've lived in London since I,was 16 – 15 years. A year ago, I moved out. I said to myself: ‘When a tour is over, you should really finish it and get away.’ When you're living in London, the show just goes on. You meet people from the music business.

“Also, the fresh location has positive effects on my work. I don't live in nowheresville, but the nearest neighbor is so far away that I can really make a lot of noise and no one will complain.”

What music do you listen to in private?

“Everything possible, only no hard rock. Mostly I like listening to singers: Chaka Khan, Steve Winwood. I really like Billy Idol's newest album [Whiplash Smile]. Jeff Beck and Allan Holdsworth are among my favorite guitarists. And now and then I like to listen to Debussy.”

Why do you keep saying that hard rock doesn't appeal to you?

“Because there's hardly any difference between most hard rock groups. You often can't tell where they're coming from.

“Okay, the Scorpions with their classical guitar style sound different than the British metal groups and their blues infusion. But in the end it's all restricted to loud guitar noise, and there's only so many notes you can get out of a guitar.”

But bands like Europe can be quite energetic.

“Spare me from Europe. They have no style of their own. They are completely unoriginal. I have absolutely no respect for them. Their guitars sound like mine, and the singer sounds like a cross between Deep Purple and the Scorpions. I find Bon Jovi better; at least they have their own style.”

Are there any plans for a collaboration with other artists?

“Really I should go into the studio with Tina Turner. But unfortunately up to now something has always come between us. The idea of making another record with someone else excites me. But it's extraordinarily difficult to find a partner with whom the chemistry is so right as it was with Phil.”

This interview originally appeared in the September 1987 issue of Guitar World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul